Myths about competition in the global economy harm humanity and our planet

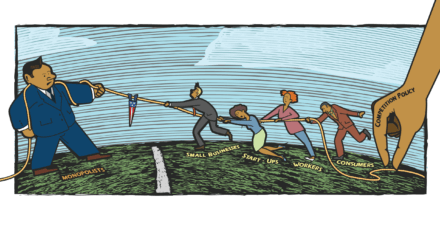

Competition around the globe is facing a crisis today. Mega corporations benefit from neoliberal ideologies and lax enforcement of the antitrust laws. Growing market power among fewer and fewer firms harms workers, new firms, consumers, and, more broadly, most of humanity and our planet. A powerful clutch of corporate executives earn more money and gain more power while workers face worsening conditions, declining worker power, and reduced pay and benefits while communities around the world suffer from growing environmental crises.

These trends underpin a new book, Competition is Killing Us: How Big Business is Harming Our Society and Planet—and What To Do About It, by Michelle Meagher. She argues that antitrust laws in the developed economies and around the globe have done little to protect not just new competitive entrants but also vulnerable communities and our planet as a whole.

Meagher, a senior policy fellow at the University College London Centre for Law, Economics and Society and co-founder of the Balanced Economy Project, calls current antitrust and corporate laws “arcane spheres of regulation” that have failed to execute upon their responsibilities. Yet she believes that a reassignment of power and a redefinition of antitrust and corporate law are the keys to holding corporate power accountable.

Meagher outlines six myths about free markets, rooted in neoclassical economic thinking, and the importance of seeing past them to stop the harms that they inflict upon our planet. Those myths are that:

- Free markets are competitive.

- Companies compete by trying to best respond to the needs of society.

- Corporate power is benign.

- We already control corporate power with antitrust laws and regulations.

- The law requires companies to maximize financial value for shareholders.

- We are all shareholders, so we all benefit from corporate focus on shareholders’ interests.

Meagher argues that current markets in free market economies are not competitive. Modern research in competition supports her claim. As now evident in the beer, homebuilding, and agriculture industries, for example, consolidation of competitors prevents the entry of new firms, thus contributing to the persistence of monopoly and duopoly power. As a result of five decades of consolidation, the four largest biotech companies controlled 85 percent of the corn seed market in 2015, compared to only 50.5 percent in 1985.

Growing evidence supports the finding that consolidation across many industries is harmful. A recent study by the Federal Reserve shows that mergers and acquisitions lead to an increase in price mark-ups and present little evidence of effects on firm-level productivity. And a deeper dive into hospital merger data finds that hospital mergers neither reduced costs nor improved the quality of care provided. The research demonstrates that when large hospital groups merge and become the only healthcare provider and employers in a region, they are able to suppress employee wages—specifically high-skilled physician and nurses’ wages—below competitive rates, a practice known as monopsony power. Decreased quality of care, increased prices, and slower wage growth are all factors that contradict the needs of society.

Meagher disputes the myth that competition results in the fulfillment of society’s needs. Instead, competition often leads firms to exploit regulatory loopholes or externalities. She explains that in the name of competition, global companies will move production to areas with weaker environmental or labor protections. While that decision allows the company to increase its profits, it results in global environmental damage done in the name of such competition.

When corporate leaders prioritize shareholder profits, they often exploit what economists refer to as “externalities” to their benefit. One such externality is pollution. Recent research found that only 100 companies are responsible for 71 percent of global emissions, and just 20 companies are responsible for 55 percent of global single-use plastic waste. Discussing how the environment is a victim of free market competition, Meagher references the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil rig explosion, an environmental tragedy that killed 11 people, caused the deaths of billions of marine life forms, and spewed 4.9 million barrels of petroleum into the Gulf of Mexico.

Indeed, investigations found that BP plc, owners of the Deepwater Horizon oil rig, resorted to unsafe construction practices after the projects exceeded their budget and timeline. BP’s eagerness to begin production drove them to compromise their workers and the environment for the sake of growing profits. To Meagher’s argument, environmental exploitation often occurs so firms can compete with one another, and as the past four decades have shown, our environment is not a benefactor of antitrust enforcement.

Meagher argues that the assumption that corporate power is benign and held in check by antitrust laws is rapidly proving to be false. Take Big Tech firms such as Alphabet Inc.’s Google unit, Facebook Inc., Amazon.com Inc., and Apple Inc. They have enjoyed decades of exponential growth, exclusivity, and influence in our socio-political environment because the courts have been unable to use existing antitrust laws to rein in their power. In return, new entrants face insurmountable barriers and workers maintain little to no power in the workplace.

Monopolistic firms argue that everyone, not just firm executives, are shareholders, and that consumers benefit from their power in the form of reduced prices and innovative products. But rising mark-ups, weakened privacy protections, and the prevalence of killer acquisitions indicate otherwise. In reality, shareholders who maintain seats on corporate boards benefit the most from consolidation and monopolistic power, while workers see declining wages and working conditions.

One of many cases in point: Despite rising market share, workers in the poultry processing industry experienced occupational illnesses at five times the frequency as other U.S. workers, and almost 75 percent of contract livestock growers live below the poverty line. Yet just this week, another acquisition in the already-uncompetitive U.S. agricultural industry is underway.

Meagher’s solution is simple: stakeholder antitrust and corporate law reform.

Minimum wage laws, pro-union laws, and wealth redistribution are valuable tools to combating unchecked corporate power, but without policies that put stakeholders above shareholders, Meagher says we are essentially “turning all the taps on full blast to fill up the bathtub without plugging the drain.” When stakeholders, consisting of firm employees, community residents, local governments, and the environment, are given a sliver of the power granted to shareholders, corporate power would effectively be used to serve the public interest rather than line the pockets of the few.

Addressing the role that power plays in free market competition and using corporate law to relay that power to stakeholders would allow policymakers to control and even curb some of the political and environmental externalities previously not considered. Participative antitrust, a term coined by Nobel laureate Jean Tirole, an economist at Toulouse 1 Capitole University, incorporates the voice of stakeholders in the development of regulative policies. Rather than fill the table with industry veterans and executives who would benefit from lax regulation, consumers, employees, suppliers, and other actors in the industry down the ladder should have a say in how new antitrust policies are built.

Additionally, Meagher suggests that corporate law can incentivize firm leaders to promote the environmental and social equities that society desires, forcing private-sector actors to consider the negative implications of their actions when competing. Broadening the scope of antitrust enforcement would require firms to address society’s needs, such as narrowed wealth gaps, environmental preservation, and worker safety, in order to compete.

In the United States, amid the coronavirus pandemic, for example, most households struggle to make ends meet due to layoffs and caretaking responsibilities while the net worth of the top 15 richest Americans has grown by almost $600 billion, or 70.85 percent. New research finds that high-temperature days result in a 6 percent to 15 percent increase in workplace injuries among some of the most vulnerable workers in our labor force, such as construction and agriculture workers.

Critics of this stakeholder theory believe that antitrust law is not the vehicle for environmental and societal remedies. One commissioner of the Federal Trade Commission, Noah J. Phillips, disputes the calls for stakeholder capitalism and the role antitrust laws play in regulating corporate power. He claims that while stakeholder goals, including stronger wages, reduced economic inequality, and environmental protections, are ideal, they do not fit into the definition of competition policy. Antitrust protects competition, and “healthy competition doesn’t always produce what is best for all stakeholders.”

While our current antitrust and corporate laws adhere to this doctrine, Meagher believes that we need to think about competition more broadly, not just about antitrust and the single mandate of seeking low prices. Expanding the scope of competition policy and corporate law can result in positive externalities such as environmental preservation and worker power.

Meagher brings up the example of B-Corps, firms that are legally bound to provide a positive impact on the environment, their stakeholders, and our society. While not perfect, these companies prioritize the public interest, from fair wages to net-zero emissions, over global growth and prove that corporations can generate profits and returns on investments while incorporating the voices of all actors. Even further, the presence of more than 2,500 B-Corps across various industries, from banking to textiles, proves that all industries are capable of serving stakeholders—it’s just a matter of corporations’ desire to do so.

Meagher concludes her book by reaffirming that our current policies fail to prevent uncontrollable power. In order to revitalize competition for a modern global economy, we must ask ourselves how antitrust law can become more meaningful. On the transformation of private entities, she makes the powerful statement that “the options for doing less harm and more good are limited only by corporate imaginations.”

For more on Michelle Meagher’s work, see the latest installment of the In Conversation series, featuring Meagher and Michael Kades, Equitable Growth’s director of markets and competition policy, in which they discuss the effects of monopoly power on the economy, environment, and society and how Meagher’s new works aim to develop the solutions.