Brad DeLong: Worthy reads on equitable growth, March 29–April 4, 2019

Worthy reads from Equitable Growth:

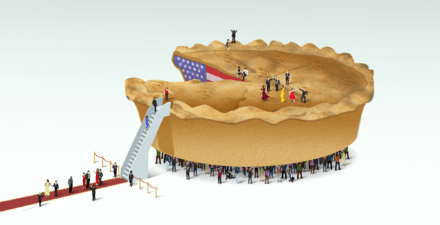

- This is brilliant. It has, I think, the implication that a lot of people in rich areas are not benefitting from the region’s wealth—which is what David Autor found in his Ely Lecture. Read Robert Manduca, “National income inequality in the United States contributes to economic disparities between regions,” in which he writes: “In 1980, just 12 percent of Americans lived in metropolitan areas with a mean family income more than 20 percent higher or lower than the national average. By 2013, more than 30 percent did. Today a handful of metros—cities such as San Francisco and Washington, DC—have mean family incomes 40 percent or 50 percent greater than average and more than double the average incomes in many rural areas … Most previous research has emphasized the role of income sorting … I show, however, that a much bigger portion of the growing disparities is due to rising income inequality at the national level.”

- Halving child poverty is attainable, and remarkably cheap, says Janet Currie, in “We can cut child poverty in the United States in half in 10 years.” She argues for: “Means-tested supports and work incentives … [m]ore universal benefits … a combination of work incentives, economic security programs, and social inclusion initiatives … [expanding] the Earned Income and Child and Dependent Care tax credits, while adding a $2,000 child allowance to replace the current Child Tax Credit … an increase in the minimum wage, and a nationwide roll-out of a promising demonstration program called ‘Work Advance.’”

- Why it is that “stress” is so debilitating in the long run is something I have never understood—especially since the forms of stress we face are not those that ought to induce a fight-or-flight use-up-the-organism’s-resources response. Is it that our brains are just too good at making long-run peril real and then transmitting that to the rest of the body? But it is clear that, here in America, “race” appears doubly poisonous. Read Kyle Moore, “Linking racial stratification and poor health outcomes to economic inequality in the United States,” in which he writes: “Racial disparities in life expectancy and incidences of sickness … are only partially explained by differences in access to economic resources … I investigate the role that stress plays in increasing the risk of hypertension and inflammation among older black and white Americans’ exposure to potential psychosocial stressors in excess of economic resources that could mitigate or offset the effects of those stressors—modifying an approach taken by the American Psychological Association.”

- A very nice look indeed at the current state of our broken antitrust system—including an excellent retrospective on the historical process by which we got here. Read Andrew I. Gavil, “Crafting a monopolization law for our time,” in which he writes: “If Section 2 is to be an effective tool for policing and deterring anti-competitive conduct in today’s economy, then it will need to be adjusted for the needs of our time. But first it is important to understand how Section 2 became so limited in scope … Choosing the language of the Sherman Act, the Congress of 1890 turned to common law, which had long prohibited ‘unreasonable restraints of trade’… [into] a statute that included prohibitions of concerted action (Section 1), as well as monopolization, attempts to monopolize, and conspiracy to monopolize (Section 2).”

- Pay transparency is perhaps the most powerful anti-pay-discrimination tool there is in America as it is today. Read Raksha Kopparam and Kate Bahn, “A judicial victory for pay transparency in the United States in the run-up to Women’s Equal Pay Day,” in which they write: “It’s important to consider the importance of a judge’s ruling last month that reinstated the collection of pay data by firms who report their employment practices to the EEOC to boost pay transparency … On March 5, 2019, the judge … order[ed] the EEOC to collect pay data in the next EEO-1 report … The ruling could not have been more timely. Just one case in point: In a survey of employees at large technology firms, 60 percent of respondents said that their employer either banned or discouraged discussion of wages.”

Worthy reads not from Equitable Growth:

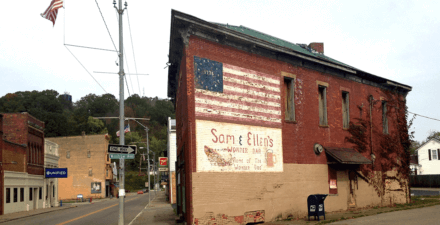

- Noah Smith’s plan for reviving rural and small-city America is to spend a fortune establishing research universities that will attract graduate students from abroad. A good many of them will then settle where they went to school. And they will then figure out how to use local factors of production to generates value in the world economy, and so revive the area. But that would require boosterish elites in the South, in the prairie, and in the Midwest. And part of the social pathology for those regions is that they do not have boosterish elites. Read Paul Krugman, “Getting Real About Rural America,” in which he writes: “Nobody knows how to reverse the heartland’s decline … Rural lives matter—we’re all Americans, and deserve to share in the nation’s wealth … But it’s also important to get real. There are powerful forces behind the relative and, in some cases, absolute economic decline of rural America—and the truth is that nobody knows how to reverse those forces. Put it this way: Many of the problems facing America have easy technical solutions; all we lack is the political will. Every other advanced country provides universal health care. Affordable childcare is within easy reach. Rebuilding our fraying infrastructure would be expensive, but we can afford it——and it might well pay for itself. But reviving declining regions is really hard. Many countries have tried, but it’s difficult to find any convincing success stories … Southern Italy … the former East Germany…. Maybe we could do better, but history is not on our side.”

- Paul Krugman makes the point, which I believe is correct, that we should not be fearing robots and Artificial Intelligence yet—that, while they may (and while I think it highly likely that they will) pose society very hard problems of income distribution in the future, there is no sign that they are at work yet on any significant scale. Our income-distribution problems today are generated by our politics, and by the resulting economic mismanagement that our politics has produced. Read Paul Krugman, “Don’t Blame Robots for Low Wages,” in which he writes: “Participants just assumed that robots are a big part of the problem—that machines are taking away the good jobs, or even jobs in general. For the most part this wasn’t even presented as a hypothesis, just as part of what everyone knows … So, it seems like a good idea to point out that in this case what everyone knows isn’t true … We do have a big problem—but it has very little to do with technology, and a lot to do with politics and power … Technological disruption … isn’t a new phenomenon. Still, is it accelerating? Not according to the data. If robots really were replacing workers en masse, we’d expect to see the amount of stuff produced by each remaining worker—labor productivity—soaring … Technological change is an old story. What’s new is the failure of workers to share in the fruits of that technological change.”

- I would not say that new technologies were “geared toward maintaining the role of human labor in value creation.” I would say that new technologies required microcontrollers—and the human brain was the only available microcontroller—and software ‘bots to manage materials and information flows—and the human brain provided the only available ‘bot hardware. In the future—but not yet now—it may become that neither of these are the case. Read Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo, “The Revolution Need Not Be Automated,” in which they write: “For centuries after the Industrial Revolution, automation did not hinder wage and employment growth because it was accompanied by new technologies geared toward maintaining the role of human labor in value creation. But in the era of artificial intelligence, it will be up to policymakers to ensure that the pattern continues … In the past three decades, the accompanying changes needed to offset the labor-displacement effects of automation have been notably absent. As a result, wage and employment growth has remained stagnant, and productivity growth anemic.”

- In a time of bubble, raising interest rates and restricting the lending of regulated institutions may be counterproductive if there are unregulated institutions as well. This is an old lesson. We forgot it and relearned it yet again in the 2000s. Read Itamar Drechsler, Alexi Savov, and Philipp Schnabl, “How Monetary Policy Shaped the Housing Boom,” in which they write: “Between 2003 and 2006, the Federal Reserve raised rates by 4.25 percent. Yet it was precisely during this period that the housing boom accelerated, fueled by rapid growth in mortgage lending. There is deep disagreement about how, or even if, monetary policy impacted the boom. Using heterogeneity in banks’ exposures to the deposits channel of monetary policy, we show that Fed tightening induced a large reduction in banks’ deposit funding, leading them to contract new on-balance-sheet lending for home purchases by 26 percent. However, an unprecedented expansion in privately securitized loans, led by nonbanks, largely offset this contraction. Since privately securitized loans are neither GSE-insured nor deposit-funded, they are run-prone, which made the mortgage market fragile. Consistent with our theory, the re-emergence of privately securitized mortgages has closely tracked the recent increase in rates.”