Weekend reading: The Unemployment Insurance benefits are not the work disincentive some claim they are edition

This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

One of the most intense debates over the next coronavirus relief package in Congress will be about whether to extend the weekly $600 supplemental unemployment insurance benefit that expires July 31. The argument in favor of ending it, or sharply reducing it, is that it acts as a work disincentive—that people won’t bother returning to work if their unemployment benefits equal or exceed their regular wages. Supporters argue that there are not a lot of jobs to return to, and that these benefits are helping families survive and supporting the overall economy. Two Equitable Growth posts this week suggest very strongly that “work disincentive” concerns are greatly exaggerated.

The first, by Kate Bahn, cites forthcoming research by Equitable Growth Research Advisory Board member Arindrajit Dube of University of Massachusetts Amherst, Ethan Kaplan of the University of Maryland, College Park, Christopher Boone of Cornell University, and Lucas Goodman of the U.S. Treasury Department. They find that that emergency Unemployment Insurance and extended benefits during and after the Great Recession did not result in higher unemployment rates for counties with longer access to benefits, compared to those with shorter access. The researchers find that overall bad economic conditions, such as those which occurred more than a decade ago and are evident again today, play a larger role in determining whether people return to work.

The second post, an Equitable Growth factsheet, points to research evidence and data from the current pandemic to show that jobless benefits have a negligible effect on unemployment levels, but that the enhancement to Unemployment Insurance is having a big impact on the U.S. economy and has set in motion a virtuous cycle that helps workers weather the economic crisis while keeping demand for goods and services from plummeting even further.

In the post-1970’s U.S. economy, the prevalence of stagnant or declining wages and the shift to “lousy” low-wage jobs and rising wage and income inequality have sometimes been attributed to a “skills gap” associated with an increasingly digital and technologically advanced jobs market. That gap, the story goes, was reflected in the college wage premium, and could be addressed simply by improving education and training. The concept of a skills gap was likewise blamed for high unemployment after the Great Recession ended in July 2009 and is now cited as the key challenge facing low-wage workers amid the current coronavirus recession. But as Kathryn Zickuhr writes in an Equitable Growth issue brief, this focus on individual workers is contradicted by recent data-driven research demonstrating that broad structural conditions constraining workers’ ability to share in economic growth—declining worker power as well as labor market monopsony, in particular—are far more important explanations. They underscore why policymakers need to improve the underlying U.S. labor market conditions for all workers, instead of shifting responsibility to those already struggling in an uneven playing field, writes Zickuhr.

This month’s entry in Equitable Growth’s Expert Focus series, which highlights scholars in our network and beyond doing important social science research, is Part 2 of our look at leading Black scholars studying U.S. economic inequality and growth. The survey, by Christian Edlagan and Maria Monroe, describes Black scholars whose cutting-edge research is influencing our understanding of the historic and persistent role that structural racism plays in driving wealth and income inequality for Black Americans particularly. Here’s Part 1 from last month.

Former Equitable Growth Ph.D. Fellow Jacob Robbins, now on the faculty at the University of Illinois at Chicago, laments the apparent loss of the bipartisan urgency that characterized policymakers’ actions at the beginning of the coronavirus recession. Not only are the health and economic crises far from over, he writes, but “we are in danger of sleepwalking into economic depression.” He makes clear that the first priority for the economy is to stop the spread of COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus, through investment in aggressive public health measures. In addition, he makes the case for extension of the weekly $600 supplemental unemployment benefit, monthly stimulus payments to households, and substantial assistance for state and local governments.

Equitable Growth announced four research grants to scholars who are pushing the frontier of knowledge on paid family and medical leave in the United States. Their research, chosen in a competitive process with vetting by outside academics and approved by our Steering Committee, will be conducted by faculty members at leading U.S. colleges and universities. The grants, totaling more than $250,000, will fund research in the areas of medical leave, caregiving leave, and employers and paid leave. This was the organization’s first Request for Proposals specific to a subject area. We will announce our new round of grantees resulting from our more general 2020 Request for Proposals later this year.

Links from around the web

“Covid-19 has shined a spotlight on the economic importance of small businesses and their physical impact on communities across the country,” writes Laura Entis for Vox. “It has also highlighted their precariousness.” She quotes Equitable Growth’s Amanda Fischer, who warns that the pandemic could be “an extinction-level event” for small businesses. Entis also points to national policies that have made it ever harder for small businesses to survive. “From tax codes that benefit multinational corporations to the erosion of antitrust laws to a health care system that puts the onus of providing insurance on employers, myriad policies favor large corporations over the interests of small business owners,” she writes.

“How Congress decides to help the tens of millions of unemployed workers during the pandemic could determine whether the stark gap between America’s rich and poor will continue to widen amid a crisis that has already hit the lowest earners the hardest,” writes Politico’s Megan Cassella. She notes that more than two-thirds of those earning a salary of less than $25,000 are now out of a job, “a number that has risen in recent weeks even as higher-wage sectors have shown potential signs of recovery.” And, Cassella writes, those least likely to have savings to lean on, the bottom quarter of wage earners, comprise one-third of jobless benefits recipients. A significant cut in the $600 weekly unemployment supplement “could exacerbate already staggering wealth and income divides, which have been growing for decades and which are larger in the U.S. than in any other nation in the G-7 … And it could hurt workers of color in particular, who are overrepresented in low-wage jobs.”

There’s a new phenomenon known as “learning pods” or “pandemic pods,” which parents—mainly white parents with significant resources—are forming to support or supplement their children’s COVID-related online education. Writing in The New York Times, Clara Totenberg Green says these pods are “small groupings of children who gather every day and learn in a shared space, often participating in the online instruction provided by their schools. Pods are supervised either by a hired private teacher or other adult, or with parents taking turns.” While they might seem like a necessary solution to the current challenges facing schoolchildren, Green writes, “they will exacerbate inequities, racial segregation and the opportunity gap within schools.” She concludes, “Paradoxically, at a time when the Black Lives Matter movement has prompted a national reckoning with white supremacy, white parents are again ignoring racial and class inequality when it comes to educating their children. As a result, they are actively replicating the systems that many of them say they want to dismantle.”

Friday figure

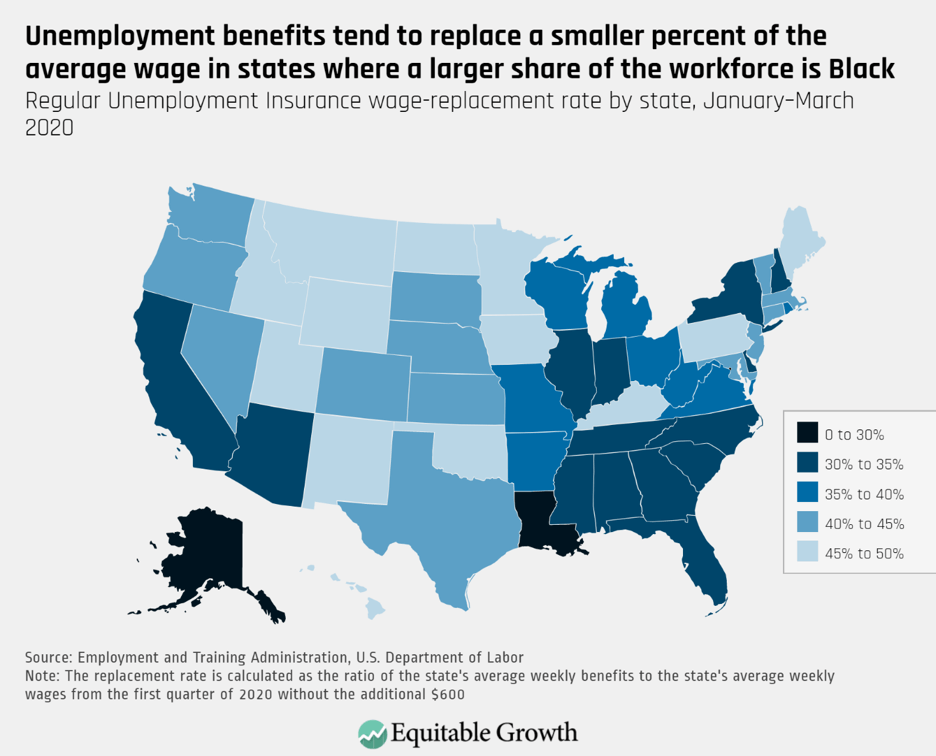

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s “Factsheet: Unemployment Insurance and why the effect of work disincentives is greatly overstated amid the coronavirus recession.”