Weekend reading: State of the Union’s inequality edition

This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

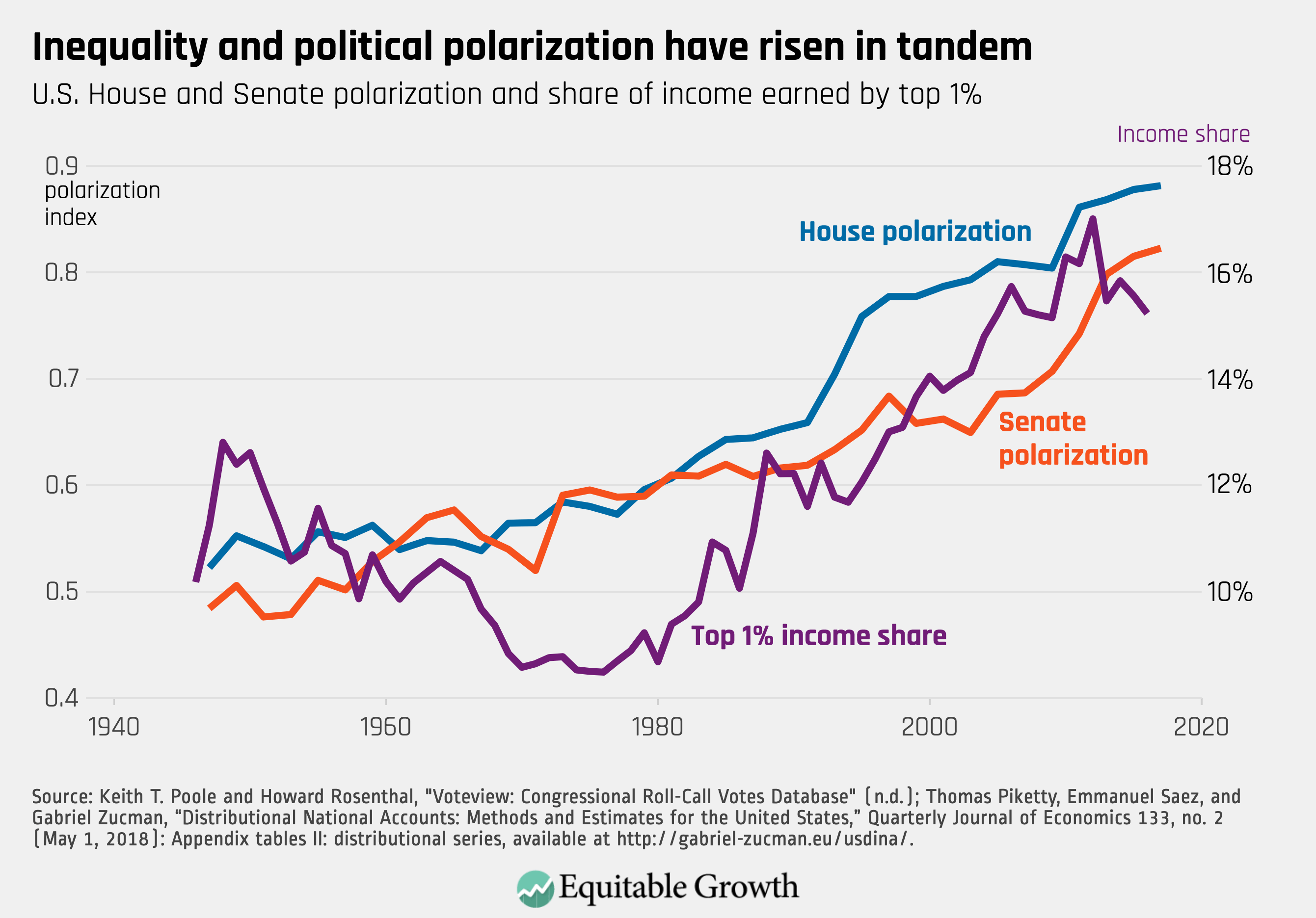

Ahead of this week’s State of the Union address by President Donald Trump, Equitable Growth released a series of graphs highlighting the way inequality restricts, subverts, and obstructs widespread economic growth in the United States—and how big-picture numbers, such as Gross Domestic Product or the unemployment rate, hide how this inequality is actually affecting average American families and businesses. The graphs show how inequality obstructs intergenerational mobility, how concentrated economic power subverts government institutions, and how inequality distorts microeconomic decisions, which consequently affects the macroeconomy. These are especially important points to remember during and after a major address such as the State of the Union, in which the economy plays a major role: “Any description of today’s economy that does not include a discussion of inequality, its causes, and its effects is at best incomplete and at worst misleading,” the post concludes.

In the second installment of her column covering the Federal Reserve, Claudia Sahm discusses another one of the Fed’s responsibilities: encouraging banks to meet the credit needs of the communities where they operate, a mandate under the Community Reinvestment Act. Hearings last week before the House Committee on Financial Services looked into how to modernize the act, which was first enacted in 1977 and updated in 1995 to address the racial and socioeconomic gaps in access to credit in the United States. While these gaps remain, the primary driver for updating the act now are changes in the banking industry and the regulatory burden on banks, as well as banks’ and communities’ desire for more transparency and clarity. In the column, Sahm goes through the history of the act, why it was first put in place, why it is still necessary, and how the act can be improved.

The House of Representatives voted this week on the Protecting the Right to Organize Act of 2019, or the PRO Act, which would make it easier for unions to organize new workers and workplaces, and ensure that U.S. workers receive fair wages and good working conditions. Ahead of the vote, Kate Bahn and Corey Husak released a factsheet about the act and how it would work to fight income inequality. They review the research from Equitable Growth’s network that bolsters the four main points of the act—addressing the power imbalance between workers and owners, clarifying the right to strike under the First Amendment of the Constitution, making it easier for workers to form a union, and preventing employers from misclassifying workers as contractors.

A new Equitable Growth working paper looks at the scope and extent of monopsony across labor markets, and is the first meta-analysis of monopsony measured by labor supply elasticity. In a column summarizing the methodology and findings of the paper, Kate Bahn explains that the researchers looked at two measurements of elasticity—direct and indirect—to show that estimation methods greatly influence findings on monopsony. The researchers also looked at specific empirical tools used to measure elasticity and aspects of research design to determine some best practices for elasticity estimation. Bahn concludes that, despite differences in methodologies, measurements, and results, it is clear that “monopsony is a broad force across labor markets and results in wage markdowns for many workers.”

Each month, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics issues a monthly report on the U.S. labor market, and this week it released the data for January. Kate Bahn and Austin Clemens put together five graphs highlighting these and other important trends in the monthly announcement.

Links from around the web

If you receive health insurance through your employer, what your employer contributes toward your healthcare may actually be (directly or indirectly) taken from your wage, according to health economists. So, asks Austin Frakt for The New York Times’ The Upshot blog, under a Medicare for All plan, when employers don’t have to spend as much to provide you with insurance, does that mean your wage will rise? While research suggests the answer may be yes for many workers, the reality may be more complicated, depending “on the nature of the labor market, which varies across markets and jobs,” Frakt writes, before going into the various possibilities in both the public and private sectors under proposed Medicare expansion plans. Ultimately, he concludes, someone will have to pay, but “to the extent the cost of health insurance is shifted away from employers and to the federal government under Medicare for all, it seems wages would rise, at least for some people.”

A recent study of tax returns shows that the tax code is not race-neutral, reports Michelle Singletary for The Washington Post, and this bias “exacerbates income and wealth inequalities.” Various loopholes, tax breaks, and other benefits disproportionately benefit white households, while African American, Hispanic, and low-income families are left at a disadvantage. While the researchers made clear they do not suggest the Internal Revenue Service is purposefully giving beneficial tax provisions to wealthy white households, they do show that the tax system and specific provisions actively impact economic inequality. Despite the parts of the tax code that typically benefit lower-income minority households, such as the Earned Income Tax Credit, Singletary writes, “the system overall still skews in favor of those who are more well off. … It’s past time to correct provisions that continue to deepen our nation’s wealth divide.”

There has been an almost 40 percent decline in administrative assistant and secretarial jobs since 2000—more than 1.6 million of these jobs have disappeared, reports Rachel Feintzeig for The Wall Street Journal. Feintzeig looks at how this trend affected the accounting and consulting firm Ernst & Young, which, in 2014, piloted a program that made deep cuts to its executive assistant staff. She writes that the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates the number of secretarial jobs will decrease another 20 percent by 2028—and another study of six mature economies by McKinsey Global Institute suggests that up to 10 million women will have to change their careers by 2030. This career path is traditionally dominated by women and has had a slower fade-out than jobs in the manufacturing industry, for example, where job losses garner much more news despite the numbers of losses in the two sectors being relatively equal over the past two decades.

A new column series from The Guardian will explore the various obstacles that women in the United States face under capitalism, from why it costs more to be a woman, to why mothers are treated differently in the United States compared to other developed economies, to how social pressure to look and behave certain ways affects women. The first of the “Feminist economics” series, by Noa Yachot and Nicole Clark, introduces many of these issues in the context of an economy that is allegedly working better than ever for women, in which women hold a (very slight) majority of payroll jobs and make up a majority of the college-educated workforce—while also facing higher healthcare costs, lower pay, and more household responsibilities than their male peers.

Friday Figure

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s “The State of the Union speech should not ignore inequality that obstructs, subverts, and distorts the U.S. economy” by Equitable Growth.