Encouraging banks to serve the credit needs of everyone

“Steady as she goes” could sum up the news from the Federal Reserve last week—that is, if we are talking about its interest-rate decision.

Monetary policy is a key mandate of the Fed from Congress—as discussed here last week. But it is not its only obligation. Importantly, the Federal Reserve also oversees many activities at banks across the country. Last Wednesday, the same day as the Fed’s vote on monetary policy, Congress held a hearing on the Community Reinvestment Act—one of the Federal Reserve’s long-standing oversight duties. These exchanges before the House Committee on Financial Services could only be described as “hang on, it’s a wild ride.”

News coverage of the hearing, such as that found here or here, as well as the hearing itself, can be hard to follow. You thought monetary policy was a black box? Debates about the Community Reinvestment Act are a bewildering mix of technical jargon and heated “she said-he said” exchanges.

So, why care? If you have a credit card in your wallet, bought a house with a mortgage, or took out a car loan, this duty of the Federal Reserve and other financial regulators affects you. If you or a family member don’t have any of the above, then the Community Reinvestment Act matters even more.

I want you to be able to follow the debate, so today, I will answer some key questions, such as: What is the Community Reinvestment Act? Why do we need it? How could we make it better? We must hold the Federal Reserve accountable to its mandate of stable inflation and maximum employment. Likewise, it needs to make sure that banks and credit markets serve Main Street.

What is the Community Reinvestment Act?

In 1977—the same year that the dual mandate was enacted—Congress gave the Federal Reserve an obligation to encourage banks to meet the credit needs of the communities where they operate. Banks cannot exclusively lend to the middle class and the rich. They cannot take deposits in a neighborhood and then choose not to serve those customers. Anyone with the ability to repay a loan, regardless of the color of their skin or the neighborhood they call home, deserves equitable access to credit. The Federal Reserve, with the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, oversee this charge from Congress.

Why do we need Community Reinvestment Act?

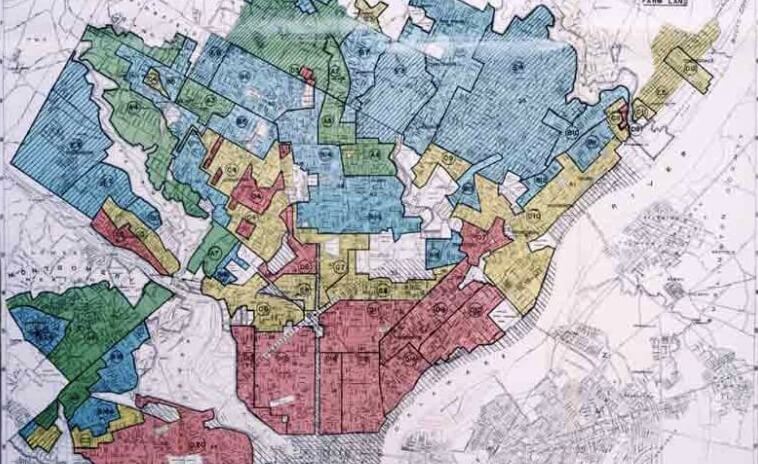

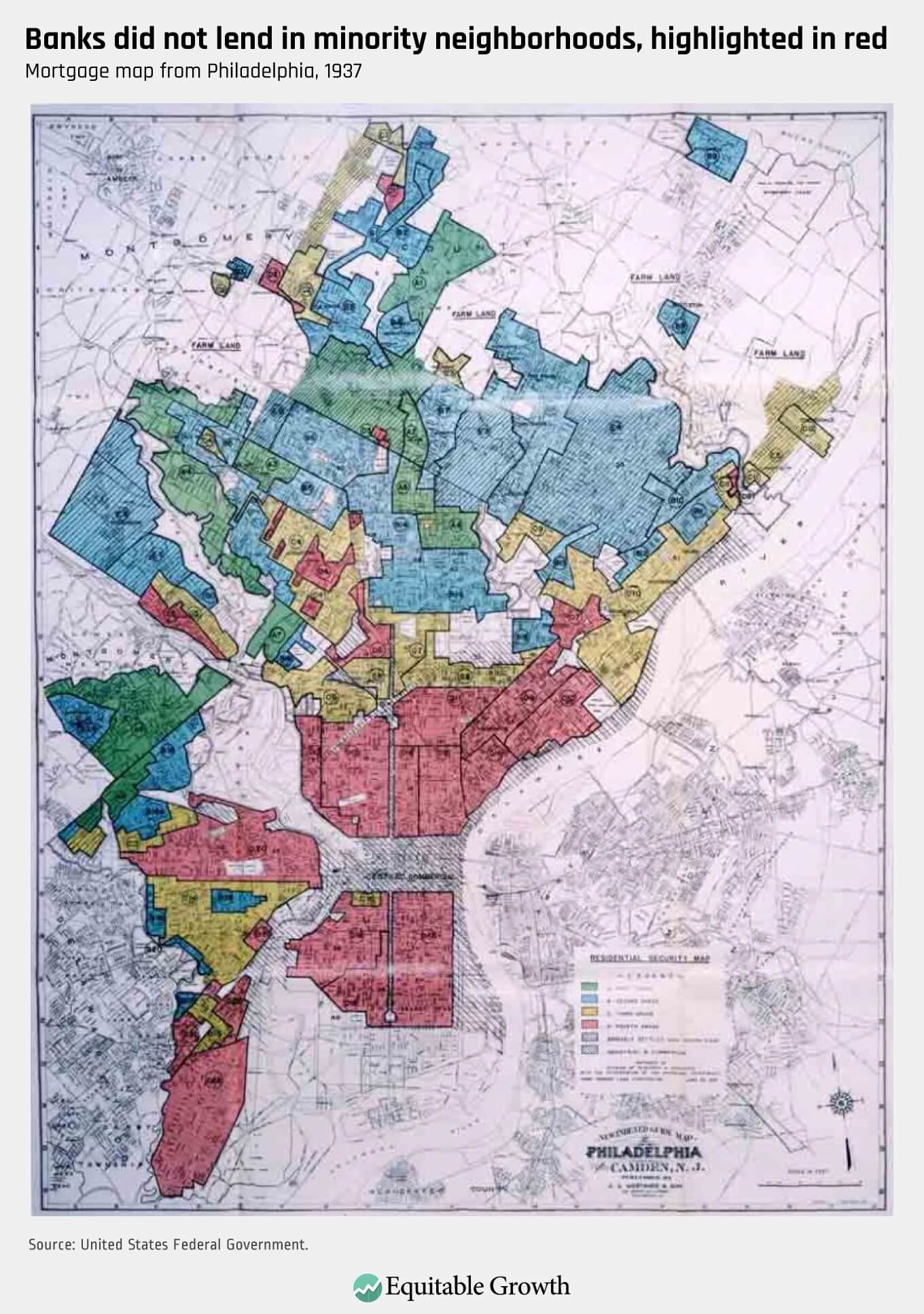

The act was born out of an ugly history of racial discrimination in lending in the United States. For more, see Richard Rothstein’s Color of Law. Until the 1960s, banks often would not lend to minorities and minority communities. The U.S. government itself drew red lines on map—a process referred to as redlining—to tell banks where they could not make mortgage loans backed by government guarantees. Again, the federal government told banks not to lend to people of color, as you can see from a redlined map of Philadelphia from the 1930s. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Leaders of the civil rights movement protested this discrimination. As one of the many voices, the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. highlighted this and other “manacles of segregation” in his “I Have a Dream” speech in 1963. Congress eventually listened and passed a series of laws to end discrimination in the U.S. housing market, including the Fair Housing Act of 1968, the Equal Credit Opportunity Act of 1974, and the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act of 1975. The Community Reinvestment Act in 1977 completed the historical legislation to fight racial segregation in housing.

How could we make Community Reinvestment Act better?

The task facing the county in 1977 was formidable. Moreover, with any regulation, the implementation and enforcement of that regulation matter. When Congress passed the act, it did not tell the Federal Reserve and other regulators how to make it happen. Together, the regulators developed criteria for banks and a process to examine their actions. Banks that fall short are limited in their ability to expand their operations or merge with other banks.

To educate banks and bring community groups into the conversation, the Federal Reserve created its Community Development function. At all 12 Reserve banks across the country, staff support the act. At the Board of Governors in Washington, the Division of Consumer and Community Affairs oversees the work across the Federal Reserve System. The Community Reinvestment Act is so important and its legacy so ugly that it demands vigorous efforts.

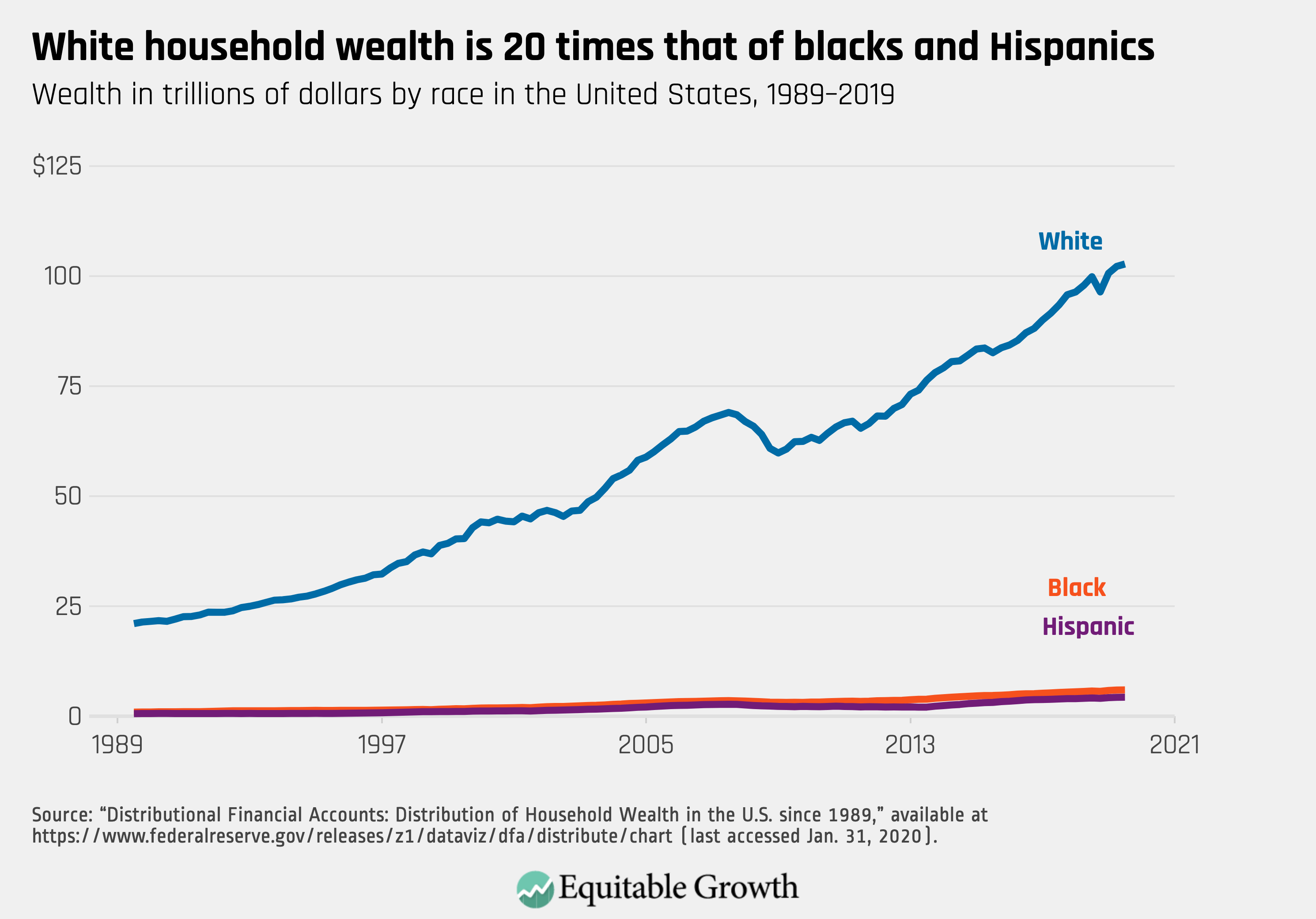

Over time, the banking industry changes, as do communities. Moreover, financial regulators learn what works and what doesn’t. In 1995, after years of public input and collaboration across the government, Congress passed a new Community Reinvestment Act. Now, 25 years later, the need to modernize the act is, again, a focus. The purpose of the act is not yet fulfilled—neighborhoods today still differ sharply and substantially by race and income. Massive differences in wealth remain. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

This time, the policy discussion is different. The driver is not racial equity. It is changes in the banking industry and the regulatory burden on banks. The desire for more transparency and clarity in the Community Reinvestment Act from both banks and community groups is valid. Unfortunately, the three agencies are not working together with a common plan.

Joseph Otting, the comptroller of the currency, set the current rethink in motion. He chose a pace faster than the prior rule writings and pushed out a proposal. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation joined; the Federal Reserve did not. Lael Brainard, a governor at the Federal Reserve Board, explained why they did not sign on at an event earlier this year: The Federal Reserve agrees that the Community Reinvestment Act is important but disagrees on how, specifically, to improve it. The fact that regulators are not moving forward together is a red flag.

Last week, Otting told the congressional Committee that he had “personally read each of 1,500 comments” on his initial proposal. Listening to the public is essential, but the public must pay attention and share its views in order for the Fed to and other regulators listen. Here’s your chance to be heard: Submit a comment before March 9 on the new proposal.