Weekend reading: Policies to foster broad-based economic growth for the next Congress and presidential administration edition

This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

As both major U.S. political parties convened over the past two weeks to officially nominate their candidates for president in 2020, Equitable Growth published a series of eight factsheets with easy-to-understand actions the next Congress and presidential administration can take to ensure broad-based economic growth for all Americans. The factsheets have descriptions of key resources Equitable Growth staff and our network have released, as well as lists of the top experts and scholars to watch in each area. Below are brief descriptions of each of the factsheets, in order of publication date.

- Unemployment Insurance is a bedrock of the social safety net in the United States, but has long experienced problems, including administrative failures, lack of a permanent system to help those left out of the program (such as self-employed workers), low benefit levels, difficulty in accessing the program, and the temporary nature of fixes that occur when recessions strike. As the coronavirus recession demonstrates, these issues cause chaos and uncertainty at the exact moment that people are most likely to need access to unemployment benefits. Equitable Growth suggests several reforms to ensure that laid-off workers are able to get the help they need.

- U.S. economic mobility is declining at the same time that inequality is rising. And Black Americans not only are more likely to experience downward mobility than White Americans but also face systemic and institutional barriers to wealth building, access to credit, and income security. Equitable Growth suggests several policies to promote mobility and address racially discriminatory structures facing Black Americans, from expanding refundable tax credits and consciously supporting wealth accumulation for low-wealth families to redirecting public investment from the criminal justice system to education and social services.

- The coronavirus pandemic and recession it caused make clear the need for automatic stabilizers, which turn economic policies and supports on and off based on certain criteria such as the unemployment rate. Making aid distribution automatic will make it easier for those in need to get the help they need and prevent the politicization of aid in Congress, freeing up policymakers to focus on new aspects of recession relief. Equitable Growth suggests that automatic stabilizers be applied to enhanced jobless benefits, direct payments to families, and aid to state and local governments.

- Wages have stagnated for most workers over the past four decades, as unionization rates and worker power have declined. The current pro-business environment tips the scales in the favor of employers, who can maximize profits by exploiting workers to produce more per hour while paying them less. Equitable Growth suggests boosting traditional labor market policies, supporting unionization, and enacting new pro-labor policies such as sectoral bargaining to reinforce worker power in the United States.

- As our economy has been bludgeoned by a public health crisis, the importance of universal paid family and medical leave could not be more obvious. The United States is the only high-income country in the world that does not have a national paid family or medical leave program for all workers. While some states offer residents access to paid leave, and a temporary federal paid leave program was passed early in the coronavirus pandemic, these solutions are not broad enough to cover all workers in the U.S. economy. Equitable Growth suggests establishing a permanent national paid family and medical leave social insurance system with inclusive eligibility requirements, progressive wage-replacement structures, robust job protections, and appropriate leave lengths.

- The U.S. tax code, as it stands, does a poor job taxing income from wealth because it allows taxpayers to defer (without interest) paying tax on investment gains until assets are sold. When they are eventually sold, the tax rate is much lower than the income tax rate. And, if taxpayers avoid selling off assets until they die, investment gains are erased, for income tax purposes. Equitable Growth suggests reforming the taxation of wealth to eliminate the two-tier system this creates, between middle-income families paying higher rates of tax on their income and wages and wealthy, disproportionately White families paying lower rates on investment income.

- Recent research suggests the United States has a monopoly problem. Market power of U.S. corporations over workers and consumers means consumers pay more for what they need, workers earn less, innovation declines, and small businesses aren’t as likely to succeed. It also grows the wealth divides in this country by boosting the wealth of executives and stockholders while workers bear the brunt of monopolies’ costs. Equitable Growth suggests strengthening the U.S. antitrust laws to counter corporate power and boosting the power and funding of the U.S. antitrust enforcement agencies—the Federal Trade Commission and the Antitrust Division of the U.S. Department of Justice.

- Small businesses are suffering during the coronavirus recession, but research indicates that the aid Congress passed earlier this year failed to prevent layoffs and bankruptcies among the smallest employers. Programs, such as the Paycheck Protection Program, provided marginal assistance to get through the worst of the shutdowns, but businesses in some of the hardest-hit areas of the country were not able to access the aid. Equitable Growth suggests restructuring business aid to rescue small businesses as quickly as big businesses, revamping accessibility and eligibility of the Paycheck Protection Program, and building up public financial systems to improve economic resilience.

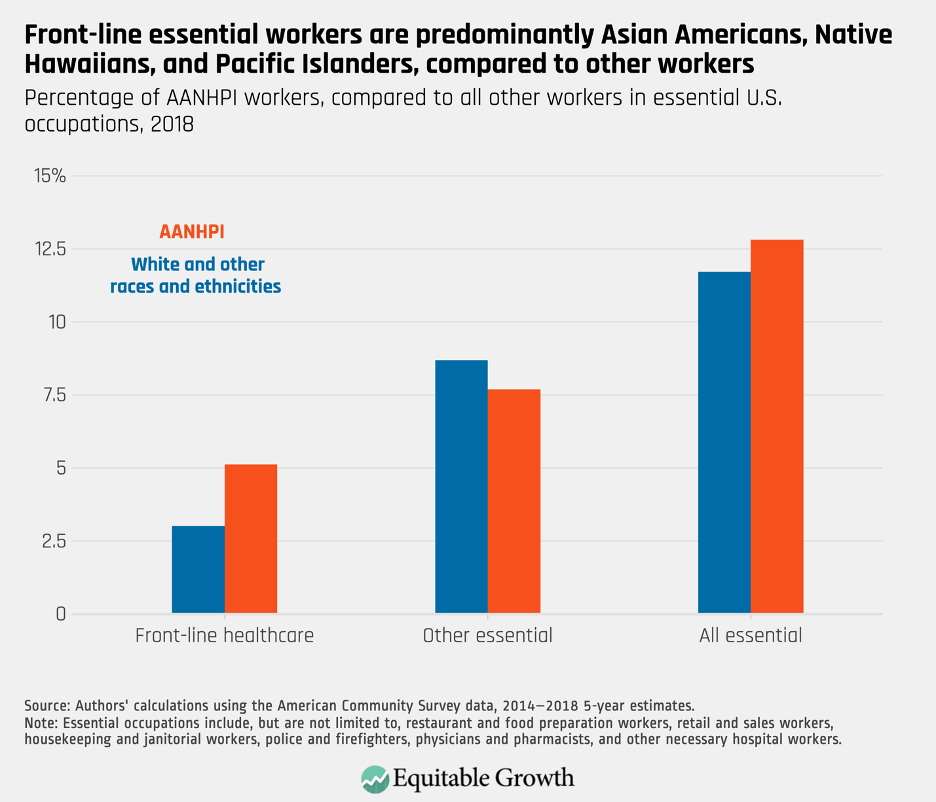

The racial and ethnic disparities facing communities of color during the coronavirus pandemic public health and economic crises as a result of systemic racism and economic inequality are clear. But the effects on Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders is less obvious because these communities are not broken out into subgroups in administrative datasets. Within the AANHPI community, there are socioeconomic inequities that will make certain subgroups more vulnerable to economic or health challenges than others. This is particularly relevant now, as front-line essential workers are predominantly AANHPI and therefore more exposed to the virus and at-risk during the pandemic. Christian Edlagan and Raksha Kopparam discuss why disaggregating the data will allow policymakers to protect the most vulnerable workers in the U.S. economy, target the unique barriers to emergency support among various AANHPI subgroups, and address systemic racism.

In 2019, Equitable Growth co-hosted an event on women and the future of work with the Institute for Women’s Policy Research, the National Women’s Law Center, and MomsRising. A new report by Susan Green summarizes the conversations, research questions, and policy proposals discussed during the event. The main focus of the event was the intersection between technology, labor, and gender. Participants explored the risks and opportunities for how new workplace tools and automation can help achieve gender equity. These new tools are changing how workers are hired, monitored, and evaluated, which raises privacy concerns and threatens to push employers to make decisions based on algorithms rather than real-life experiences. Discussing these issues and finding solutions to them will be essential to ensuring more equitable, safe, and productive workplaces in the future.

Links from around the web

Black workers are more likely to be unemployed during the U.S. economic downturn, but are less likely to gain access to unemployment benefits, write ProPublica’s Ava Kofman and Hannah Fresques. Record numbers of workers are receiving Unemployment Insurance, thanks to both the vast number of jobs that have been lost as well as Congress’s temporary expansion of unemployment benefits to gig economy workers, part-time workers, and independent contractors. But despite being overrepresented in these nontraditional occupations, a smaller percentage of Black workers who have been laid off are receiving jobless benefits. This can partly be explained by geography, with many states in recent years making it harder than others to apply for and receive unemployment benefits and reducing the amounts given to those who do get them. But there’s more to the story than where workers are living. Kofman and Fresques examine the various historical and structural barriers and deterrents for Black workers to access Unemployment Insurance programs across the United States.

A set of maps in The New York Times reveals that neighborhoods in cities across the United States that were redlined in the 1930s are significantly warmer today than areas that were not. Redlining is a racist housing practice designed to withhold real estate investment in areas with mostly Black populations, effectively reducing homeownership rates among Black families, with consequences and implications for wealth building lasting through today. These neighborhoods, which tend to still be poorer and have more residents of color today, are an average of 5 degrees Fahrenheit hotter in the summer than wealthier and Whiter parts of the same cities, write Brad Plumer and Nadja Popovich. This is probably because they consistently have fewer trees or parks, which cool the air, and more paved surfaces or nearby highways that absorb and radiate heat. This not only has obvious consequences for residents’ health and lives—during a heat wave, every single degree increase in temperature can increase the risk of death by 2.5 percent—but also will continue to worsen with climate change.

While it is impossible to know for sure what the trajectory of the coronavirus recession and recovery will be, some economists estimate that it could look a lot like the devastating and lengthy recovery from the Great Recession of 2007–2009. Characterized by long-term unemployment, the Great Recession was brutal for many workers, who permanently lost their jobs, irreparably severing ties between employer and employee. And now, 6 months into the recession, writes Andrew Van Dam for The Washington Post, many workers who initially reported that they believed they’d be back to work soon are actually losing their jobs permanently. This is a worrying trend considering that long-term and permanent unemployment are both huge drags on an economic recovery. Whether this dire scenario is avoided, economists say, depends in large part on whether the coronavirus pandemic can be contained.

Child care providers are facing lower wages and financial losses, confusing new safety standards, and higher risk of exposure to the coronavirus and COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus, and many workers are leaving their jobs or being laid off as a result. In the Los Angeles Times, Rikha Sharma Rani looks at the state of California specifically, where almost 9,300 child care providers, or 1 in 4 in the state, have closed since mid-March. More than 1,200 of those closures will be permanent, Sharma Rani reports, eliminating almost 20,000 child care spots. This has far-reaching implications for economic recovery, as accessible child care is an essential part of reopening and getting families back on their feet. And with the pandemic still raging with no end in sight, it’s unclear how much worse it will get.

Friday figure

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s “Disaggregated data on Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders is crucial amid the coronavirus pandemic” by Christian Edlagan and Raksha Kopparam.