The coronavirus recession is severe, and the damage to the U.S. economy will last years

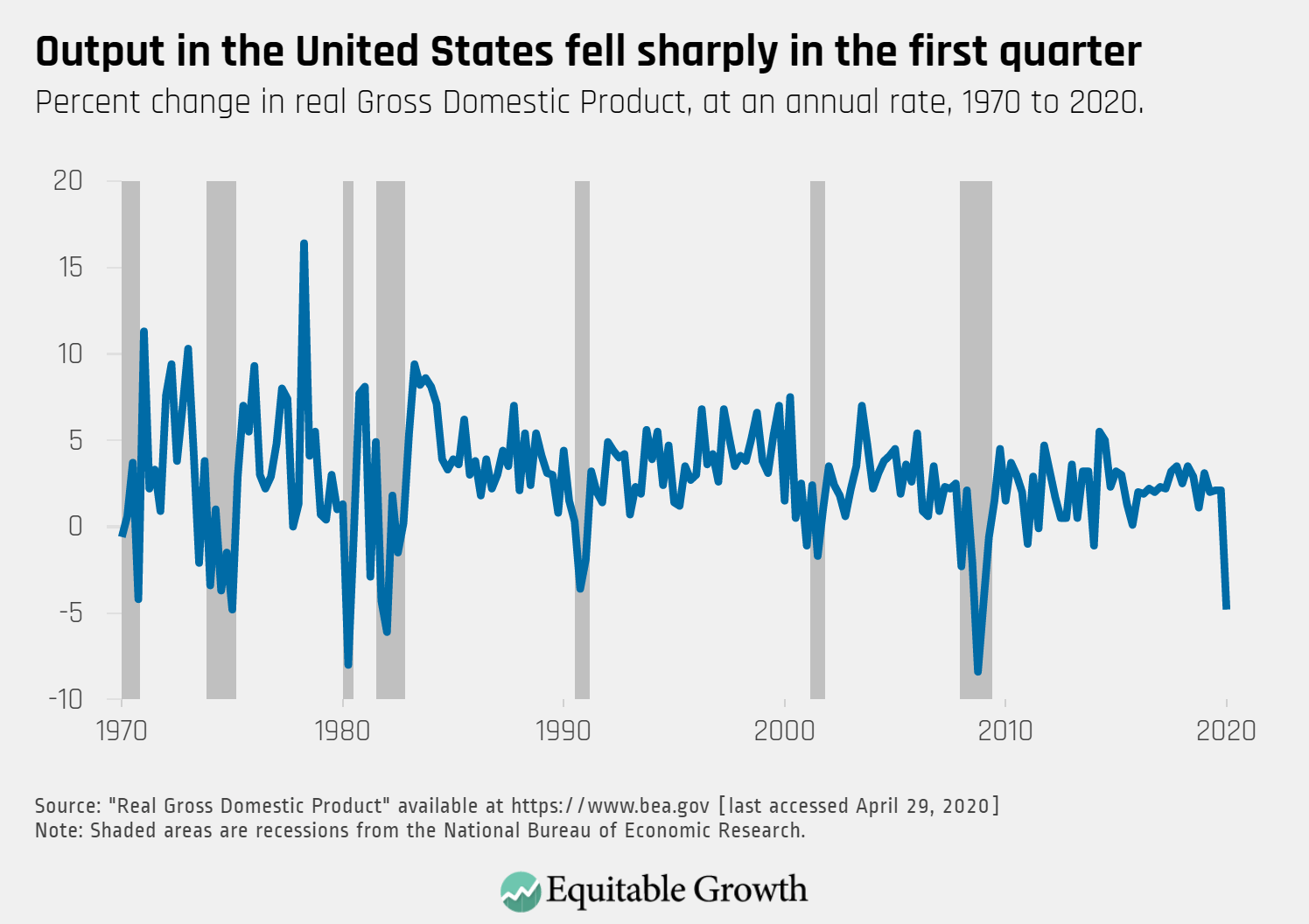

I shared my views on the coronavirus recession on March 24, at a virtual conference that economists Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman at the University of California, Berkeley organized. My remarks drew on my experience as a forecaster at the Federal Reserve Board during the Great Recession and its slow recovery. The conference took place 3 days before the president signed the $2.2 trillion relief package. A month later, sadly, my pessimistic outlook then remains correct today. In fact, we learned this morning that real Gross Domestic Product dropped 5 percent at an annual rate in the first quarter. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

The drop in consumer spending on services can more than account for the decline, and stay-to-home orders in March weighed on spending. In addition, real personal income was flat in the first quarter, after rising 1.5 percent in the fourth quarter of last year. Keep in mind, that March has relatively little weight on first-quarter GDP. The worst is yet to come. Second-quarter GDP will be shockingly bad. The largest quarterly decline in GDP since 1948 is 10 percent. We are on track to blow past that record soon.

I began my presentation—back in March, well before these shocking data came rolling in—with a stern warning that the U.S. economy is in a severe recession, at least twice as severe as 2007–09. The official recession dating committee will eventually tell us that February 2020 was the peak in economic activity, and thus the start of the coronavirus recession. It is as obvious now as it was a month ago.

My first macroeconomic forecast at the Fed was January 2008, a month after the Great Recession began. I studied that recession. I studied its recovery. My job was to follow the U.S. economy in the moment. In addition, I did research then—and still do now—on policymakers’ efforts to support families. I know today is bad, really bad for everyone.

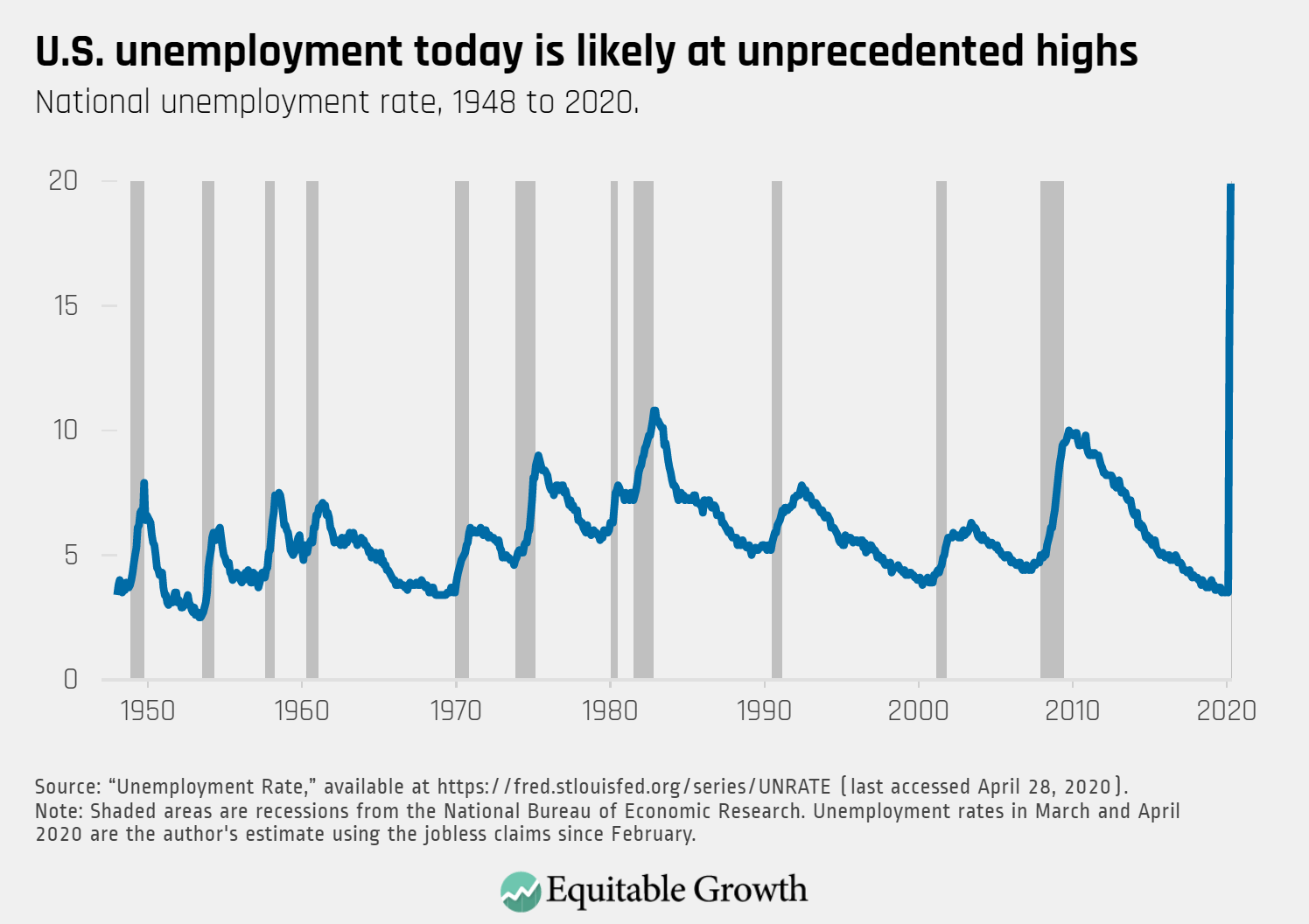

We are living a heartbreaking reversal from the best of times to the worst of times. In February 2020, we had an unemployment rate of 3.5 percent, continuing more than a decade of more jobs year after year. Millions of people who, frankly, had been written off were finally finding work. That world is now gone.

Nearly 30 million workers have filed for jobless benefits since the beginning of March. As I said before, layoffs will continue. They have. With jobless claims alone, I estimate the unemployment rate is now at more than 20 percent. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Today’s national unemployment rate is rivaled only by the heights of the Great Depression, when 30 percent of workers were unemployed. Lost income leads to less spending, which leads to business closures and more layoffs. This recession is the first to be caused by a pandemic, but the downward spiral looks like all the rest, albeit much more severe.

U.S. policymakers had advance warning. The coronavirus began overseas. It spread first across Asia, and some countries such as South Korea fought back with some success. Then, on March 8, my heart sank when the Italian government closed its northern region—that’s when it became clear the United States did not have the virus tests or tracking capability needed to get ahead of the curve of the pandemic. We could not be South Korea. We were going to be Italy, with the coronavirus and the COVID-19 disease it spreads shutting down our economy. The temporary closure of public commerce would certainly have dire economic consequences. It did, and it will.

So, let’s talk now about what’s at risk in terms of dollars. U.S. consumers are the engine of our economy, spending about $15 trillion dollars per year. That accounts for 70 percent of Gross Domestic Product. These are big dollars, and we are not spending now. We have “the mother of all demand shocks” upon us.

Stores are closed, and people are staying home. Many physical barriers now exist to spending, but people still have to pay the bills to keep a roof over their head and the lights on. Many will have to cut back when they lose paychecks and as they fear they will lose their jobs in the future. People and businesses are living with overwhelming anxiety.

Policymakers need to do more than contain the coronavirus and allow stores to reopen. They need to get money in the pockets of people and calm their fears. If Americans have money to spend, they will spend. Many have no choice. Their low wages make it impossible to support their families in good times, let alone now.

Congress and the Federal Reserve began to step up support for families and businesses in March, for both public health and financial relief. They have done much more in the past month. On March 27, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Stability, or CARES Act, became law and set aside $2.2 trillion in relief. It included nearly $300 billion in rebates to families, more generous jobless benefits, and a new Payroll Protection Program to get money to small businesses. The relief programs are not perfect, and they will not be enough. But they are a start and are getting money out—money that will make a very severe recession a little less very severe.

The Federal Reserve has rolled out many programs over the past two months to support the U.S. economy and keep financial markets working. They cut the federal funds rate to zero in March and have launched many lending facilities. The Fed is fulfilling its role as the lender of last resort, and it has had to work hard to keep markets from breaking down.

In April, the Federal Reserve took a big step and began providing relief directly to Main Street. Congress gave the Fed the authority and the funds to lend to medium-sized businesses and municipalities. Loans, in particular, to state and local governments will help some communities with their budget shortfalls. But, most of all, families, businesses, and municipalities need money. Loans come with a risk. The outlook is uncertain, and many fear they will not be able to pay down the road. Congress needs to send money, with no obligation to repay.

I want to be clear, even with relief from Washington, immense damage is happening across country right now. This is not a drill. The Great Recession showed how long it can take to get us back on our feet. This time, it will be worse.

What does the economy look like on the other side of this recession? Anyone who says they know what the recovery will look like is just blowing smoke. No one knows. The containment of the public health crisis will determine the economic bottom, and efforts to keep it under control will shape the U.S. economy in the coming year.

We have so many unanswered questions about the damage from this recession. Questions on how many workers lose their jobs, on how much income disappears, and on whether our nation’s social safety net even holds up. Our joint state and federal employment insurance system was neglected for decades. We have the thinnest of safety nets, and now, we have millions of workers applying for benefits every week. I’m very concerned that the safety net could break down regardless of how much money Congress approves. The big dollars only matter if it gets to people.

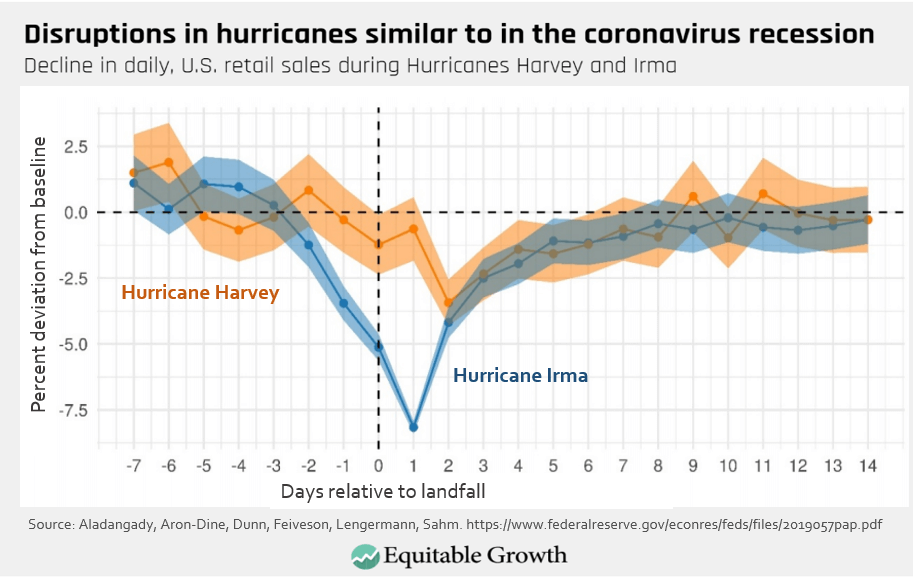

But back to the recovery. I think it’s useful to think of the coronavirus recession as a huge natural disaster. It’s something akin to a Category 5 hurricane, with entire country in the eye of the storm for 2 months. Let me put some data behind this scenario. With colleagues at the Federal Reserve, I studied the economic effects of Hurricanes Harvey and Irma in 2017. Daily spending at retailers and restaurants in the path of the hurricane declined sharply during the storms. The hit was big, and lost spending was not made up quickly. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

Today, the coronavirus pandemic continues to ravage the United States and countries around the world. Unlike hurricanes, however, the effects of the coronavirus are not isolated and not short-lived. Even when our nation eventually beats the virus, the cleanup from our current disaster will be hard. To underscore—this recession will create lasting damage to the economic well-being of families, businesses, and communities. It will take many years to get back what we lost.

Policymakers cannot throw in the towel. They must commit to stay the course and provide relief until we are all back on track. Congress walked away too soon after the Great Recession, and that made the recovery painfully slow. Congress must not repeat that mistake. They should use a trigger based on economic conditions to determine when the relief can be phased out. Passing programs for 6 months or a year will waste time in debates on the Hill and risks aid stopping too soon.

Above all, the unemployment rate tells us when we are in a recession, and it tell us when we have recovered. The coronavirus recession is so unprecedented that any predictions about this fall and winter—let alone next month—are impossible. We do not need to guess. Congress can enact legislation and the Federal Reserve can commit to a plan that lets workers tell us when they are back on track.

Policymakers must learn that lesson from the Great Recession. They cannot leave too soon. We need their help.