Testimony by Michelle Holder before the Joint Economic Committee on robust government investments

Michelle Holder

Washington Center for Equitable Growth

Testimony before the Joint Economic Committee,

Hearing on “Building on a Strong Foundation: Investments Today for a More Competitive Tomorrow”

April 27, 2022

Introduction

Thank you, Chair Beyer, Ranking Member Lee, Vice Chair Heinrich, and members of the Joint Economic Committee, for inviting me to speak today. It’s an honor to be here virtually.

My name is Michelle Holder. I am the president and CEO of the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, an organization that seeks to advance evidence-backed ideas and policies that promote strong, stable, and broad-based economic growth. I also serve as an associate professor of economics at John Jay College, which is part of the City University of New York.

Since 2013, Equitable Growth has provided more than $7 million in grants to more than 300 researchers aiming to understand how economic inequality—in all its forms—affects growth and stability. The evidence demonstrates that the decades-long trend of increasing inequality hurts both families and the long-term trajectory of the U.S. economy.

Crucially, this trend is not the result of natural, iron laws of economics. Rather, increasing inequality is the result of a long history of policy decisions that have prioritized ideology over evidence. Making different policy decisions—such as robust government investments—can help reverse inequality and make our economy stronger and more resilient.

In what follows, I will detail how the federal government has already begun to make these different policy choices during the current economic recovery from the COVID-19 recession. I will then focus on two key areas where government investments can build on the foundations of the recovery and play a critical role in promoting economic growth that can be shared by all—the manufacturing sector and green energy, with particular attention to manufacturing’s past and green energy’s future. As I will demonstrate, investments in both of these sectors are vital for promoting racial equity and boosting economic growth.

Indeed, the costs of inaction are severe. Mary Daly—president and CEO of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco—and colleagues examine differences from 1990 to 2019 among White, Black, and Latinx men and women ages 25 to 64, and find if economic outcomes and opportunities were more equitably distributed, nearly $23 trillion would be added to the U.S. economy. Further, writing for Equitable Growth, Robert Lynch of Washington College finds that closing racial and gender disparities would result in an increase in U.S. Gross Domestic Product by $7.2 trillion and would have totaled $28.6 trillion instead of $21.4 trillion in 2019.

Lynch also finds that federal, state, and local tax revenues would have been $1.82 trillion higher in 2019 while the overall U.S. poverty rate would have dropped from 10.5 percent to 6.6 percent, lifting 12.2 million people out of poverty in 2019. What’s more, there would have been a $429 billion improvement in the finances of the U.S. Social Security system in 2019.

Government investments are an essential tool for helping to attenuate these disparities and are therefore an essential tool for strengthening our economy. We need to look no further than the present moment to understand the powerful role that government investments can play.

A strong recovery

The COVID-19 recession was quite unlike business cycle downturns of the past. When the pandemic began to spread across the United States in March 2020, its impact was immediate and severe. The U.S. unemployment rate skyrocketed from a 50-year low of 3.5 percent in February 2020 to a post-Great Depression high of 14.7 percent in April of that same year. Over the same period, the U.S. labor market shrank by more than 20 million jobs. Industrial production plummeted. And the U.S. economy contracted by 3.4 percent in 2020—the worst economic downturn since 1946. Job losses did not closely follow patterns from past recessions.

The COVID-19 recession also entrenched disparities in U.S. labor market outcomes for women of color, especially Black women. As my colleagues Janelle Jones, former chief economist of the U.S. Department of Labor, Thomas Masterson of the Levy Institute, and I find, Black women were bearing the brunt of early job losses during the pandemic. This was primarily due to occupational segregation. That is to say, there exists an overrepresentation of Black women in certain industries and occupations as a result of a myriad of factors, including the systemic devaluation of certain kinds of work, discrimination, and uneven occupational integration.

Even prior to the pandemic, Black women experienced significant occupational segregation, with five occupations accounting for more than half of all the jobs in which Black women work. This is consistent with a large body of economic literature that shows women, including Black women, tend to be crowded primarily in low-wage occupations. My colleagues and I find that this already-high occupational segregation worsened during the pandemic and ensuing recession. The extraordinary nature in which economic activity was slowed or halted—particularly among the kinds of service-sector and care jobs that could not be performed remotely—disproportionately affected Black women precisely because they were more likely than many other demographic groups to be employed in these service and care occupations. More than half of all employment losses for Black women were concentrated in just four occupations in which women, generally, are crowded.

The COVID-19 recession therefore reflected and reproduced existing occupational segregation, leading to disparate U.S. labor market outcomes and uneven job losses. At the onset of the pandemic, occupational segregation by race and gender all but ensured that the COVID-19 economic decline was not equally shared.

Nevertheless, the unprecedented recession was met with an unprecedented recovery. In the 2 years that followed, the U.S. government enacted major pieces of legislation to respond to dual health and economic crises. The COVID-19 recession officially ended in April 2020, but the federal policy response extended well into 2021 to ensure a robust economic recovery. By the end of 2021, real U.S. GDP annual growth hit 5.7 percent.

Between March and April 2020, the U.S. Congress passed four major pieces of legislation, the most consequential of which being the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act. The CARES Act included provisions to expand eligibility and provide extra support to workers through the Unemployment Insurance system, additional funding for food assistance through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, loans and guarantees for small businesses through the Paycheck Protection program, and Economic Impact Payments.

The next year followed with the American Rescue Plan, signed into law in March 2021. It included an extension of many CARES Act programs, as well as new initiatives such as the expansion of the Child Tax Credit. The unprecedented speed and size of the American Rescue Plan and the CARES Act helped millions of workers and households withstand the economic pain brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The bounce back in GDP, for example, was much quicker in the United States than in most other high-income countries. The overall average unemployment rate is now close to its pre-pandemic level. And workers in the bottom of the wage distribution have been experiencing real wage growth. Labor demand has skyrocketed, giving workers more power to negotiate higher pay and better working conditions.

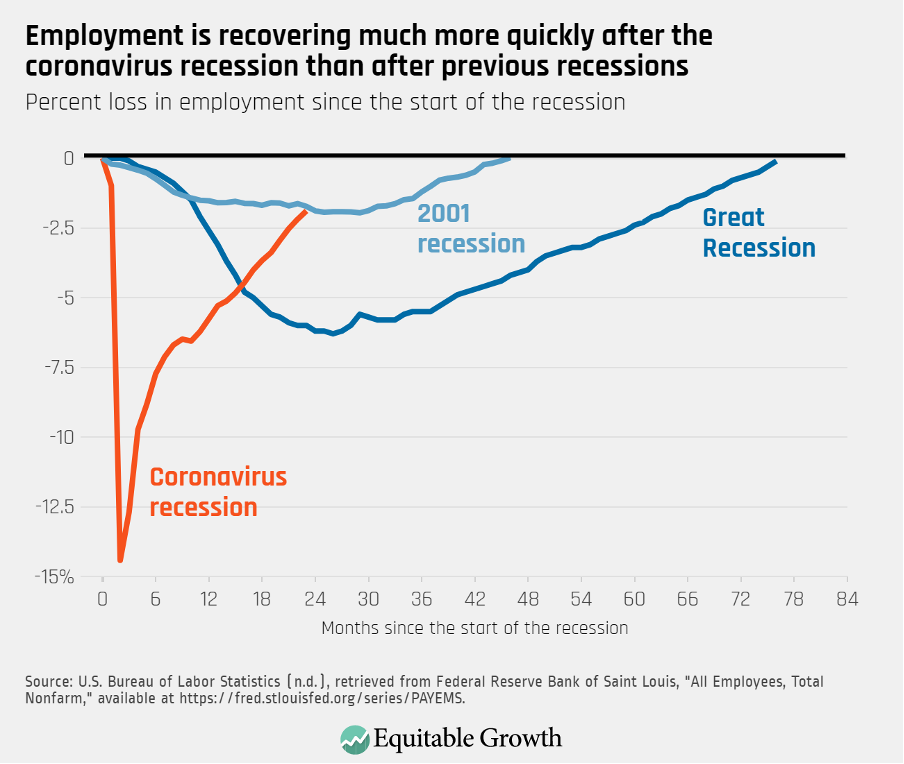

As such, job openings in the United States reached a record high of 11.1 million in July 2021—an almost 60 percent increase from February 2020—and have remained elevated since. The jump in open positions has been particularly stark in industries such as manufacturing and leisure and hospitality. Indeed, the recovery in overall employment has been extraordinarily quick, compared to previous U.S. economic downturns. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

One of the more powerful policies that came from the federal government’s response was the expansion of the Child Tax Credit. By providing families with monthly income support to supplement their own earnings and help offset rising prices, the enhanced credit lifted an estimated 3.7 million children out of poverty. It also helped reduce racial disparities in household income, as poverty rates fell drastically for Black and Latinx children. This type of policy is a clear blueprint for success.

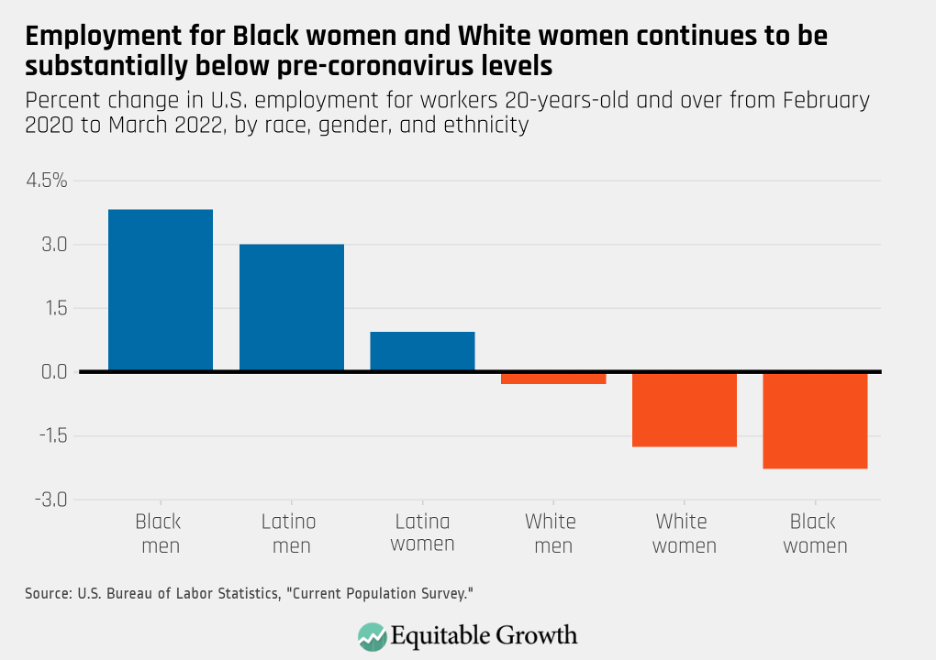

While inequities in the U.S. labor market remain persistent, employment gains made by Black women and Latina workers suggest the recovery efforts are reaching those who are often the last to recover from a recession at a much quicker pace than previous recessions. The fiscal response to the COVID-19 pandemic is directly responsible for the swift recovery we’re experiencing today. With economic growth still strong, there exists a real opportunity to continue to make government investments to ensure the recovery is not just strong, but also equitable and thus more enduring. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Manufacturing

The government investments fueling the recovery from the COVID-19 recession represent just one potential pillar for promoting a stronger and more resilient economy. Government investments in the manufacturing sector represent another.

It is well understood that investments in manufacturing played a large role in driving U.S. economic growth in the 20th century. The period of the highest rates of annual economic growth was during World War II—peaking at 18.8 percent in 1941—when the government had a considerable and essential hand in planning industrial policy. Yet three key elements of this story are often overlooked.

First, government investments in manufacturing had a significant role in expanding economic mobility for the U.S. population. Second, the gains accruing to Black workers as a result of this transformation were short-lived, attenuated in future generations by racist policies that prioritized policing over social infrastructure. Third, the widely reported loss of jobs in the manufacturing sector in the 1990s and beyond had racially disparate effects, especially in the Black community. I will briefly unpack each of these key elements in turn.

During World War II, the U.S. government financed an industrial expansion that resulted in a threefold increase in manufacturing output over 4 years. Economists Andrew Garin of University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and Jonathan Rothbaum of the U.S. Census Bureau examine the effects of these government investments in manufacturing plants on mobility in the postwar period. They find that in U.S. counties where these plants were built, employment rose by 30 percent and average production wages rose by 10 percent after the war, with both remaining elevated through 2000.

They also find that in places where these plants were built, upward intergenerational household income mobility for children born to parents with below-median family incomes in 1940 increased. By helping support better-paying jobs, these investments proved to be a critical factor in achieving economic mobility for some workers.

Manufacturing also has historically been a sector that provides the dual benefit of economic mobility for Black male and Latino workers without a college degree and a driver of productivity growth for the overall U.S. economy. From 1910 through 1970, more than 6 million Black Americans migrated from the South to Northern, Midwestern, and Western states during what is known as the Great Migration. The period of 1940 to 1970 was particularly stark, with more than 4 million Black Americans migrating during this time.

The drivers behind the Great Migration are myriad, including attempts to escape the overt racial violence of the Jim Crow South and seeking economic opportunity in Northern industrial cities. As explained by historian Joe William Trotter Jr. of Carnegie Mellon University, from the beginning of World War I through 1930, Black workers increased from 600 in the auto industry to nearly 26,000, from 17,400 to 45,500 in the steel industry, and from 5,800 to 20,400 in the meatpacking industry.

Due in part to the expanding employment in the industrial and manufacturing sectors, some Black workers referenced Northern, Midwestern, and Western cities in terms such as “Promised Land,” “New Jerusalem,” “Land of Liberty,” “Land of Hope,” or “land of milk and honey.” The economic data suggest this conceptualization of economic mobility was partially true, at least for a moment. Economist Leah Boustan of Princeton University highlights that some estimates indicate Black agricultural workers migrating from the Southern United States who switched to an industrial occupation in the North were able to increase their earnings by as much as 300 percent. Using cutting-edge empirical research, Boustan finds that when accounting for standards and costs of living, a Black man from the South could have increased his earnings by 130 percent by moving North in 1940.

And yet these increased earnings did not necessarily translate into long-term gains. In a working paper, Princeton University economist Ellora Derenoncourt finds that while the first generation of migrants profited from a mass exodus from the South, the gains they accrued and hoped to pass on to their children were slowly eroded for several reasons, especially related to Northern White civil society backlash to the Great Migration. In the wake of the Great Migration, Northern cities funneled public funds toward policing while investment in social infrastructure stagnated. Simultaneously, White flight to the suburbs and an overall erosion of the urban environment helped transform destination metropolises of the 1940s and 1950s into highly segregated opportunity deserts by the 1990s and 2000s.

Moreover, despite economic gains made during the Great Migration, Carnegie Mellon’s Trotter highlights the discriminatory working conditions that Black workers still faced during this time, with managerial and labor policies ensuring the racial stratification of the workforce. Steel industry supervisors, for example, arbitrarily fired Black workers and replaced them with White workers. One Detroit automaker proclaimed, “We hired them [Black workers] for this hot dirty work and we want them [to stay] there. If we let a few rise, all the rest will become dissatisfied.”

When recognizing the historical importance of the manufacturing sector for providing a path for upward mobility—with increased wages in union jobs—it is equally important to recognize the structural and policy factors maintaining racial stratification and limiting mobility.

Nevertheless, manufacturing remains an important sector in which to invest because of its pathways for mobility and clear effects on economic growth. A recent Economic Policy Institute report finds that Black, Latinx, Asian American and Pacific Islander, and White workers without a college degree all earn substantially more in manufacturing than in nonmanufacturing industries. For median-wage, non-college-educated employees, Black workers in manufacturing earn $5,000 more per year—or 17.9 percent more—than in nonmanufacturing industries. Latinx workers earn $4,800 more per year, or 17.8 percent more. AAPI workers earn $4,000 more per year, or 14.3 percent more. And White workers earn $10,100 more per year—29 percent more than in nonmanufacturing industries.

This “manufacturing premium” is due in large part to higher rates of unionization in the manufacturing sector, which help to correct for artificially suppressed wages brought on by employers’ power to underpay workers. In a separate report, Lawrence Mishel of the Economic Policy Institute finds that, relative to other sectors, manufacturing workers have a benefits advantage, primarily in insurance and retirement benefits, and this advantage, in fact, increased from 1986 through 2017.

The problem is, manufacturing employment in the United States has been steadily declining for decades, and productivity in manufacturing has been slowing. The decline in manufacturing has been stark and its effects have been uneven. Economist Eric Gould, writing for The Centre for Economic Policy Research, finds that the decline in manufacturing between 1960 through 2010 led to a significant decrease in wages and employment for Black workers and a significant increase in racial gaps for labor market outcomes. The deterioration in high-paying jobs in the manufacturing sector, especially for men with less formal education, is substantial. Gould’s findings include a 13.3 percent decline in mean, full-time wages for Black men, an increase in the poverty rate of 8 percentage points for Black women, a 9 percentage point increase in poverty for Black children, a 12 percent increase in the racial wage gap for men, and a 3.4 percentage point increase in the racial gap in male employment.

Research also indicates that declines in manufacturing partially explain decreases in Black employment rates. Economist William Spriggs and his co-authors find that trade policies causing significant reductions in U.S. manufacturing employment disproportionately affected Black workers. In assessing the industries most exposed to these trade policies, such as manufacturing, they find a 3.2 percentage point reduction in the share of overall Black working-age employment (ages 15 to 64) for every 1 percentage point increase in import exposure.

The decline of U.S. manufacturing has led to both a decrease in the quantity and the quality of manufacturing jobs. This is due to a myriad of factors, including rising contingent work in manufacturing, anti-union “right-to-work” laws in locations with significant manufacturing in the South, and vulnerability to demand shocks. Further, research suggests that in recent decades, employers have used automation technologies in manufacturing and other industries not to increase productivity, but rather to de-skill jobs and lower wages.

Promoting job quality and worker power as a cornerstone of the manufacturing sector is critical to ensuring that previous benefits of a robust manufacturing sector are realized in the contemporary economy. Bolstering protections and pathways for labor organizing, such as the measures included in the Protecting the Right to Organize Act, will help ensure manufacturing includes worker voices on technological integration, support the connection between workforce training and employment, and ensure workers are sharing in the value that they create. Trade unions, for example, are effective partners in providing apprenticeships, continuing training, and portable benefits.

Government investments in “high-road” supply chains—that is, supply chain networks that collaboratively aim to benefit firms, workers, and consumers alike and, crucially, that do not suppress wages to compete—can help embolden worker power and stimulate broadly shared growth. Economist Susan Helper of Case Western Reserve University, writing for Equitable Growth, argues there is clear precedent for these kinds of investments. The U.S. government can act as a high-road purchaser and preferentially buy from companies that are innovative—as it did to jumpstart the semiconductor industry. The federal government also can require its suppliers to pay “prevailing wages,” as is required in government-funded construction by the Davis-Bacon Act—a requirement that helps support apprenticeships and training centers.

Government investments also could include offering technical assistance to its own and others’ suppliers by expanding the Manufacturing Extension Partnership, which provides technical support for small and medium-sized manufacturers, and the U.S. Department of Energy’s Industrial Assessment Centers, which help firms redesign their operations to conserve energy. Furthermore, investments in robust supply chains may also help curb inflation by helping to ease bottlenecks.

Without a robust manufacturing sector, broad-based growth will be difficult to achieve. One of the key drivers for productivity growth in manufacturing is innovation. Economist Mariana Mazzucato of University College London details that the most innovative firms have benefited the most from public investment. But research shows that the misallocation of talent in science and engineering—through harassment and discrimination, disparate access to development and training opportunities, and occupational segregation—are costly for the innovation workforce, and therefore for the manufacturing sector.

Addressing gender and racial disparities in access to advanced manufacturing jobs is essential to boost dynamism in the sector. For instance, economists Lisa Cook at Michigan State University and her co-author Yanyan Yang estimate that U.S. GDP per capita could rise by between 0.6 percent to 4.4 percent if more women and Black Americans were included in the initial stages of the innovation process.

These barriers are present across industries and education levels. Women make up about a quarter of the manufacturing workforce but are heavily underrepresented in some of the occupations that have historically provided a pathway to the middle class for workers without a college degree, such as machine tool operators and welders. Women also face sexual harassment at higher rates in male-dominated industries such as manufacturing, which obstructs on-the-job well-being.

While employment in the U.S. manufacturing sector is now near its pre-pandemic level, the erosion of the manufacturing earnings premium and bad-quality working conditions could lead to slow job growth in the sector in 2022 and beyond. While goods-producing sectors such as manufacturing did not see the massive employment losses that services-providing industries experienced in the first months of the pandemic, employment in the sector never fully recovered from the previous two recessions.

Indeed, manufacturing-sector employment reached its peak in the late 1970s and has been declining somewhat consistently ever since. Currently, employment in the sector is 35 percent below its 1979 level. Federal research and development spending is at a 60-year low, which means less knowledge creation, fewer good jobs, and a harder time boosting employment in new sectors. Investments in manufacturing—ranging from high-road purchasing, R&D spending, equitable trade policies, and tax subsidies—can therefore decrease inequities in the economy and help bolster growth.

Green energy

Building on the foundations of the economic recovery and the manufacturing sector, government investments in green energy, technology, and training can help address longstanding inequities by providing this pathway to workers of color today. With the current strong recovery, there is ample opportunity to make key investments in green energy that help to ensure growth is broadly shared and power imbalances in the U.S. labor market are addressed. Federal investments in energy research and development are low compared to prior years’ levels, and there is clearly room to invest.

Recent economic research demonstrates the importance of investments in green energy. For instance, Columbia University economist Joseph Stiglitz argues, alongside other colleagues, that renewable energy and energy efficiency investments typically have high multipliers, delivering even greater returns over time. They also create more jobs, including ones that can’t be taken offshore, such as those in home energy retrofitting.

Moreover, according to recent research from Heidi Garrett-Peltier, an economist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, for every $1 million invested in renewable energy or energy efficiency, almost three times as many jobs are created than if the same money were invested in fossil fuels. Investing more money in the fossil fuel industry will not address high and growing unemployment rates. Indeed, the Federal Reserve is not even requiring companies to keep workers as a condition for getting loans in the fossil-fuel industry.

Investments in training also can be a path to ensuring the benefits of green energy are broadly shared. For instance, Historically Black Colleges and Universities, or HBCUs, are at the forefront of training for green energy jobs. Indeed, 24 percent of all Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics, or STEM-related bachelor’s degrees earned by Black students in the United States were conveyed by HBCUs.

This type of training will be necessary to ensure that a transition to green jobs is equitable, but it is not sufficient. As the Washington Center for Equitable Growth’s Director of Labor Market Policy and Chief Economist Kate Bahn explains, inadequate wages are not the result of a skills gap, but rather derive from a lack of worker power to collectively bargain for fairer wages. Increasing wage floors and worker power will be key to ensure there is not simply access to green jobs, but also that these green jobs are equitable.

Writing for Equitable Growth, Leah Stokes and Matto Mildenberger, both assistant professors of political science at the University of California, Santa Barbara, outline ways to ensure that the high multipliers and job creation from green energy investments are equitably shared. One such mechanism is Community Benefits Agreements, which are contracts between large energy developers and communities hosting an energy project. These agreements require that the community receive a share of the project’s benefits.

In the few offshore wind developments in the United States, for example, these agreements are already in place. Policymakers could provide extra incentives for projects that receive government subsidies or tax benefits to negotiate Community Benefits Agreements. These agreements also could require minimum wage standards, unionization, or other equitable labor market arrangements.

Regarding union requirements specifically, Stokes and Mildenberger highlight that many U.S. unions maintain strong ties to carbon-intensive industries, such as auto manufacturing or heavy industry. By contrast, many jobs in the clean energy sector—from clean energy deployment to electric vehicle manufacturing—remain nonunionized. In part, this reflects secular decline in union participation across new U.S. economic sectors. In order to address labor market disparities—such as gender and race wage gaps—government funding for clean energy projects should prioritize unionized jobs.

In this vein, there is already precedent at the state level for ensuring green energy jobs are more equitable in labor market power. Washington state, for example, tied labor standards to tax incentives for renewable energy development through the Clean Energy Transformation Act in 2019. The bill contains, among other provisions, business tax incentives on high-road labor standards and practices, such as apprenticeship utilization, a prevailing wage, local hires, and the use of Project Labor Agreements and Community Workforce Agreements, helping to promote good jobs.

Conclusion

There is clear precedent and ample opportunity for government investments to promote growth and address the harmful consequences of economic stratification in our nation. To make the U.S. economy more resilient and equitable, we need to build off the strong foundations of the current recovery. I thank you for the chance to submit this testimony on how you can do just that in the manufacturing and green energy sectors.