January Jobs report: U.S. employment growth surpasses expectations, but it is essential to boost job quality in manufacturing

The U.S. economy added 467,000 jobs between mid-December and mid-January, according to the most recent Employment Situation Summary by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Even with COVID-19 cases reaching an all-time high in the first weeks of January, employment growth surpassed projections. Upward revisions to previously published employment growth estimates for November and December now put the 3-month average at 541,000 jobs gained.

Almost 1.4 million workers joined the U.S. labor force last month, yet the overall unemployment rate rose slightly from 3.9 percent in December to 4 percent in January. The share of 25- to 54-year-olds currently working—an indicator also known as the prime-age employment-to-population ratio—rose slightly from 79 percent to 79.1 percent. Additionally, because of the omicron-fueled surge in COVID-19 cases, 3.6 million workers were absent from work due to illness in January.

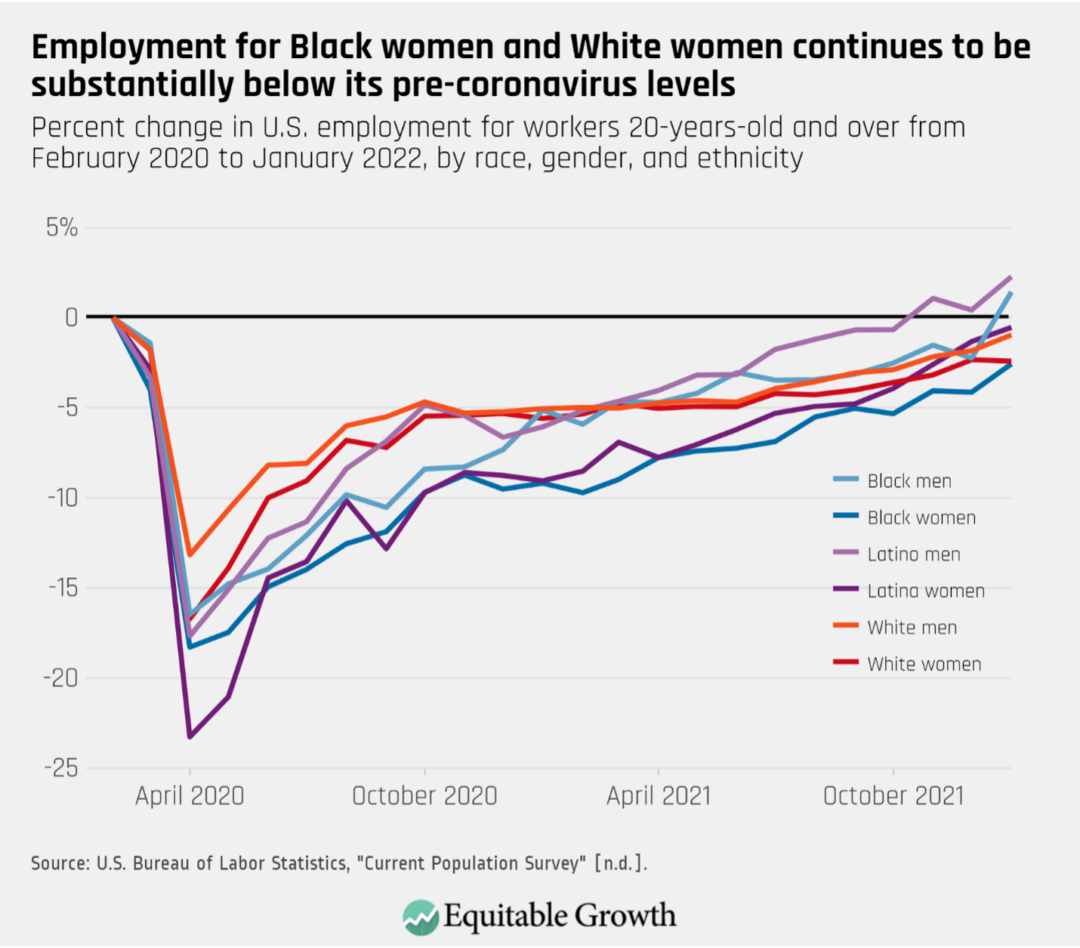

In addition, jobs growth was varied for different demographic groups of workers. Employment gains for most groups was robust, but White workers saw a slight increase in unemployment and the employment rate for men was unchanged while continuing to improve for women. Yet Black women, who have seen the weakest jobs recovery since February 2020, saw a significant increase in their employment rate, alongside a decline in unemployment. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Across sectors, jobs added were greatest in the leisure and hospitality sector and the professional and business services sector, which added 151,000 jobs and 86,000 jobs, respectively. The manufacturing sector also registered a net increase in employment in January, with 13,000 jobs added, but this key sector also suffered substantial disruptions due to the latest wave in the rolling coronavirus pandemic.

As the spread of the omicron variant picked up in December, the country reached a record number of daily cases, and millions of workers stayed home either because they were sick with the coronavirus themselves or because they were caring for someone who was. Understaffed factories and operations troubles—along with the pandemic-driven boost in demand for goods such as furniture and car parts—increased pressure on already-burdened workers and manufacturers.

In the manufacturing sector, job openings and quits are near record highs

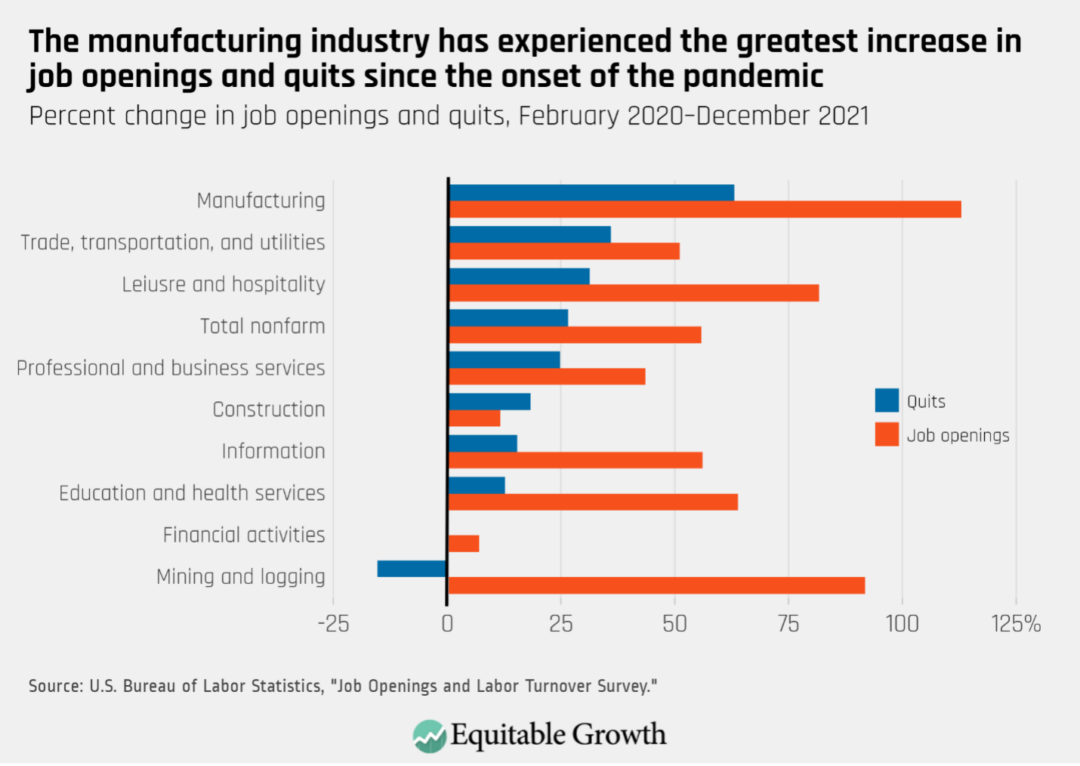

Indeed, there are signs that the manufacturing sector is going through an important adjustment. Across industries, the number of workers quitting their jobs and the number of job openings have hit record-breaking highs within the past year, but no other industry has seen a larger increase in either its number of quits or job-openings relative to its pre-pandemic levels than manufacturing. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

There are a number of explanations for these record-high trends. One is that the pandemic made manufacturing an even more dangerous industry. Many manufacturing plants were designated critical infrastructure and allowed to continue operating during the peak of the early 2020 pandemic, when many other sectors were in lockdown, yet employers often did not provide personal protective equipment, follow social distancing protocols, or provide paid sick days to workers.

A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report in 2021 examined high-density workplaces, specifically food processing and manufacturing plants, finding they were at high-risk for coronavirus transmission. Because only about a third of manufacturing workers can telework, the coronavirus crisis made an industry that already had high rates of injuries and illnesses even more dangerous.

Pay and job quality in the manufacturing sector has been in decline for decades

Other reasons why manufacturing workers are leaving their jobs at record rates are difficult work conditions, understaffing, care responsibilities, insufficient pay, and labor market conditions that are providing opportunities for workers to move on to other jobs. Many of these pay and job-quality problems, however, have plagued the manufacturing sector for decades.

A pre-pandemic study by the Economic Policy Institute found that, on average, manufacturing workers continued to have an advantage in terms of pay over comparable workers in other industries, but this premium declined between the 1980s and the 2010s. One of the key reasons behind the erosion of both of these job advantages, the study proposes, is an increased reliance on outsourcing, since workers employed through staffing agencies are paid significantly less than workers employed directly by manufacturing firms.

This decline in the manufacturing earnings premium, and in job quality more generally, set the stage for important disruptions during the coronavirus recession and the continuing pandemic today. In addition, the erosion in pay has been particularly stark for workers without a college degree and coincided with a generalized decline in labor standards, lack of government investment in infrastructure, and falling union membership rates both in the manufacturing industry and across the U.S. economy.

For instance, a recent analysis finds that lack of investment in infrastructure and trade imbalances have been greatly harmful for manufacturing-sector workers in general and for Black workers in particular, whose share of the manufacturing workforce saw a large decline in the 1990s and early 2000s. There is also evidence that the decline in manufacturing has widened Black-White income and employment divides. Research additionally suggests that in recent decades, employers have used automation technologies in manufacturing and other industries not to increase productivity but rather to de-skill jobs and lower wages.

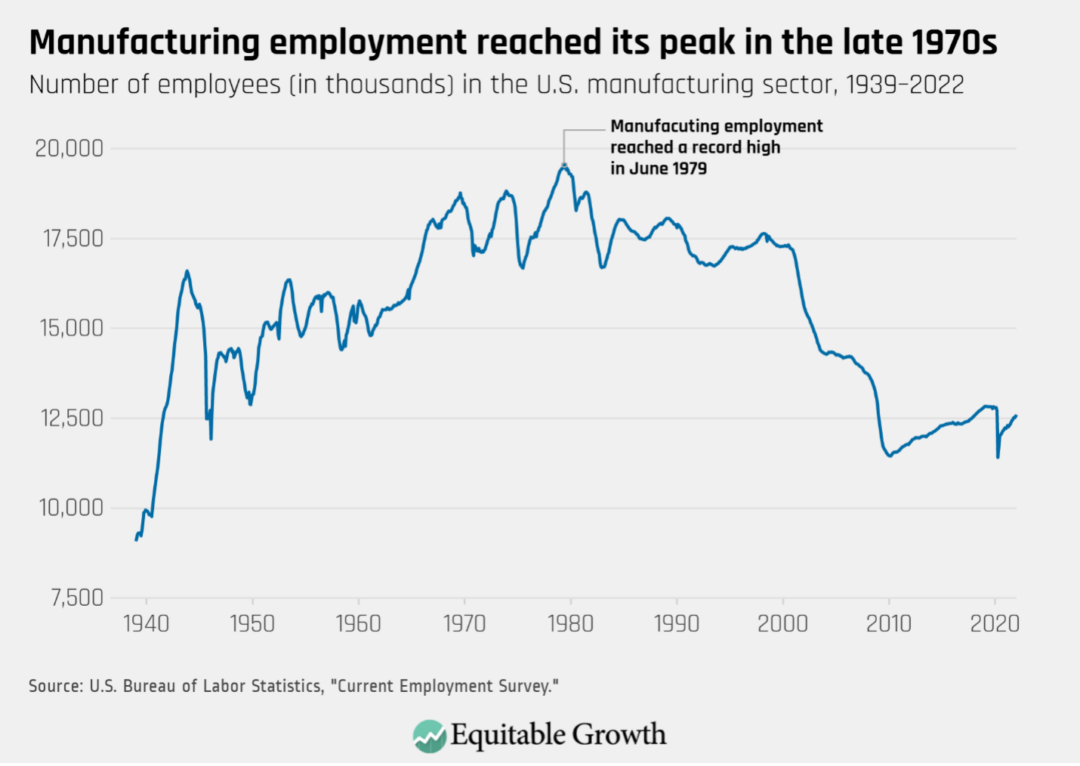

While employment in the manufacturing sector is now near its pre-pandemic level, this erosion of the manufacturing earnings premium and bad-quality working conditions could lead to slow job growth in the sector in 2022 and beyond. While goods-producing sectors such as manufacturing did not see the massive employment losses that service-providing industries experienced in the first months of the pandemic, employment in the sector never fully recovered from the previous two recessions. Indeed, manufacturing-sector employment reached its peak in the late 1970s and has been declining somewhat consistently ever since. Currently, employment in the sector is 35 percent below its 1979 level and 1.8 percent below its February 2020 level. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

Boosting job quality and inclusion in the U.S. manufacturing sector is essential for workers and the economy writ-large

As the U.S. labor market continues to recover, it will be essential to boost efforts to protect workers and their communities through the effective enforcement of labor standards, both during the pandemic and beyond. Indeed, manufacturing sites have been a major driver of the pandemic’s spread, especially in the early days of the pandemic, and poor workplace protections continue to place the country’s supply chains at risk. Meatpacking plants in particular appear to have been a significant source of COVID-19 cases and deaths, especially in many rural areas.

Transforming U.S. supply chains to create good jobs

January 14, 2021

More broadly, manufacturing companies need to come to terms with their history of exclusion and create pathways to correctly allocate talent and boost innovation to attract workers and foster economic dynamism. Policies that support organized labor and boost union membership will also create pathways to increased job quality and safety for workers in the sector. In addition, the federal government can support the creation of good jobs by, for example, building out much-needed infrastructure and buying manufactured goods from firms that pay high wages, provide good benefits, and provide quality workforce training. These measures will help create more good jobs for workers in the manufacturing sector, boost productivity, and drive broad-based and resilient U.S. economic growth.