Fast facts

- Industrial policy is making a comeback in the United States. Recent laws enacted by the U.S. Congress and signed into law by president Joe Biden highlight how there is renewed interest in the federal government taking on a more active role in protecting key sectors of the U.S. economy and creating pathways to meet key national goals.

- Supporting good jobs in the United States is one of these key goals as the country upgrades essential infrastructure, jumpstarts the clean energy transition, ensures the U.S. economy produces key technologies, and builds more resilient supply chains.

- Industrial policies are more effective at supporting and lifting job quality in the United States when they are accompanied by strong collective bargaining laws and institutions, just as there were throughout much of the mid-20th century—when institutional support for worker power played an essential role in the manufacturing sector in creating secure, well-paying jobs.

- When institutional support for labor waned in the 1970s as U.S. labor laws changed or were reinterpreted in ways more favorable to employers, union membership and job quality both started to deteriorate.

- Today, massive new investments mobilized by recent industrial policy legislation are a historic opportunity to ensure federal dollars support good jobs. Indeed, these laws already include a number of labor standards and programs that will foster good working conditions.

- Ultimately, the most effective measures to ensure that the jobs created through industrial policies are good jobs are the same measures needed to boost job quality throughout the entire economy, among them U.S. labor law reforms and other efforts to boost worker power, including strengthening the system of income supports and raising the federal minimum wage.

Overview

Interest in industrial policies as tools to address the climate crisis, reach national security goals, and boost domestic economic growth and innovation is surging, with more and more policymakers and researchers seriously considering the possible advantages of the U.S. government taking on a more active role in promoting and protecting key sectors.1 Further, industrial strategy also is now a large and important component of the current administration’s economic agenda, with recent legislation enacted by the U.S. Congress and signed into law by president Biden representing a shift toward the use of public investments to spur private investments, expand the country’s productive capacity, and boost innovation and growth.2

But in addition to jumpstarting the clean energy transition, updating essential infrastructure, and ensuring the United States can produce key goods and continue to develop new cutting-edge technologies, one of the great promises of a new industrial policy era lies in its potential to narrow economic disparities and support good jobs in the United States.3

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, for instance, is designed not only to lower carbon emissions and deploy historic investments in energy infrastructure, but also to create millions of stable and well-paying jobs over the next decade.4 Likewise, the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 aims to boost the country’s semiconductor production capacity, build more resilient supply chains, and revitalize employment in the U.S. manufacturing sector.5 And the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021 is expected to both update the country’s essential infrastructure and lift job quality and quantity in industries such as manufacturing, transportation, and construction.6

For industrial policies to support job quality in the United States effectively and ensure public- and private sector investments results in stronger and more equitable economic growth, however, they need to operate in a context where there is institutional support for workers. Indeed, revitalizing the domestic manufacturing sector, investments in public infrastructure, measures aimed at boosting productivity, and other industrial policies can be important tools for creating good jobs if they are accompanied by strong collective bargaining laws and institutions, just as they were throughout much of the mid-20th century.7

High union membership, for example, played an essential role in making the manufacturing sector of the post–World War II era a source of secure and well-paying jobs, but as union membership density fell beginning in the 1960s so did job quality in the sector.8 The now weakened protections around workers’ right to strike used to allow workers to successfully leverage work stoppages, with research finding that strikes were once an effective mechanism to boost wages.9 And the strong collective bargaining laws and institutions of the mid-20th century were key for allowing many workers to more fully share in the economic value they created, establishing stable worker-employer relationships, and narrowing overall income inequality.10

Today, however, union membership is a third of what it was in the 1940s and 1950s.11 Legal changes that enabled the enactment of right-to-work laws, the use of so-called captive audience meetings, and other anti-union tactics have shifted bargaining power away from organized labor and toward employers.12 As the National Labor Relations Board—the federal agency in charge of protecting workers’ right to organize—lost power, resources, and began to reinterpret the National Labor Relations Act in a way that was more favorable to employers, its ability to safeguard collective bargaining rights and push back against unfair labor practices declined.13 All in all, employers’ hostility toward organized labor grew at the same time that the laws and institutions that protect workers’ right to bargain collectively started losing power and influence.14

This report makes the case that U.S. policymakers who believe creating good jobs is an important goal of a new industrial policy agenda should also seek to boost workers’ bargaining power and support measures that make it easier for workers to form and join unions, such as those included in the Protecting the Right to Organize Act.15

In the first section of this report I detail what job quality is, why it matters for both workers and the broader U.S. economy, and the essential role that worker power plays in improving working conditions. The second section discusses why industrial policies are much more likely to meet their potential to support good jobs if they are implemented alongside steps to strengthen worker power and collective-bargaining institutions. I then examine some of the key provisions and programs embedded in recent industrial policy legislation that aim to improve job quality.

I then discuss what existing empirical research finds about the effects of these policies on workers, employers, and the overall U.S. labor market. I close this report with a discussion of the measures that, together with industrial policies, can deliver better employment conditions for U.S. workers and foster broadly shared economic growth, including:

- Policy interventions to increase workers’ bargaining power through the enforcement of labor standards

- Policy interventions to increase workers’ bargaining power across entire sectors

- Policy interventions to increase workers’ bargaining power across the U.S. labor market

Current and future U.S. industrial policies represent an historic opportunity to lift job quality, drive innovation, and foster broadly shared economic growth. These efforts will be much more effective if industrial policymaking is paired with steps to boost worker power across the United States.

Improving job quality benefits both workers and employers, and supports stronger economic growth and innovation

While there is not a single definition or list of attributes that determine whether a job is high or poor quality, good jobs broadly offer fair wages, safe working conditions, family-sustaining benefits, stable schedules, opportunities for upward career advancement, mechanisms to prevent and address unfair treatment at work, and access to collective bargaining.16 For U.S. workers and their families, then, access to high-quality employment opportunities is associated with a long list of positive life outcomes.

Research finds, for instance, that good working conditions and job security are linked to lower levels of stress, better mental and physical health outcomes, reduced likelihood of experiencing hunger, and higher lifetime earnings.17 Research also shows that job security provides protection against negative shocks to family well-being.18

In addition to improving the lives of workers and their families, high-quality jobs are good for employers’ bottom lines. Better jobs often lead to lower turnover rates, which in turn lower businesses operation costs and increase revenues.19 High-quality employment opportunities are also a key driver of economic competitiveness, with recent research finding that higher wages and good working conditions spark greater productivity growth and product innovation.20

Firms that offer higher wages, more opportunities for training, and better benefits tend to outperform their competitors in terms of customer satisfaction.21 Likewise, a review of the economics literature by researchers at the high-income nations’ Organization for Economic Cooperation shows that good working conditions and job satisfaction are associated with higher worker productivity, financial performance, and firm survivorship rates.22

Broad-based access to high-quality employment opportunities also can address longstanding inequities and, as a result, lead to stronger economic growth. For instance, a study by economists at the University of Chicago and Stanford University finds that the U.S. economy experienced important productivity gains as more historically marginalized workers faced fewer barriers to access high-paying professions.23 Specifically, this team of researchers shows that more women workers and more Black workers entering high-wage jobs that were a good match for their skills explains about two-fifths of growth in aggregate U.S. output between 1960 and 2010.

Similarly, recent research finds that because the existing wage divide between Black and White workers leads to inefficiencies and a misallocation of talent in the U.S. labor market, closing this gap would lead to a substantial increase in aggregate income.24

By some key measures, job quality is lower today than in the 1970s

Despite the wide-ranging benefits of good jobs, there is a large body of research finding that job quality in the country fell between the late 1970s and the mid 2010s.25 As perhaps the clearest manifestation of a decline in working conditions, over this period the typical U.S. worker experienced slow wage growth and the incidence of low-paying jobs rose.26 There also was a generalized increase in job insecurity and a dramatic rise in earnings inequality.27

By some estimates, the wages of the top 1 percent of workers grew by more than 160 percent between 1979 and 2019 while wages of the bottom 90 percent of workers increased by only 26 percent.28 During those four decades, a Congressional Research Service report shows, the wages of workers without a college degree fell and the real wages of the very lowest earners stagnated, after factoring in inflation.29

Depending on the measure used to account for inflation, real hourly earnings for production workers and workers who are not supervisors grew somewhere between 0 percent and 26 percent between 2019 and 1979.30 Regardless of what statistics are used, the pace of annual wage growth was substantially slower between the 1970s and 2010s than between the 1960s and the 1970s.31

The rise of wage inequality and slow earnings growth for most U.S. workers had important implications for the structure of the labor market. For instance, the University of Minnesota’s Job Quality Index—a statistic that captures the share of private-sector jobs in the United States that pay above average and below average weekly wages—shows that while in 1990 there were 94 high-paying jobs for every 100 low-paying jobs, by 2019 there were only about 80 high-paying jobs for every 100 low-paying jobs.32

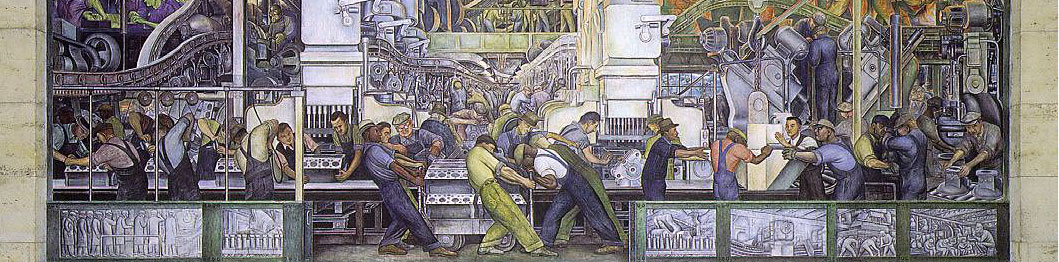

Likewise, in one study operationalizing job quality over the past four decades, David Howell at the New School shows that the share of young U.S. workers without a college degree who earn poverty-level wages saw a big jump between the late 1980s and the mid-2010s.33 Specifically, Howell finds that by 2017 about 70 percent of young women and 57 percent of young men without a college degree worked in what the author calls “lousy jobs.”34 This share not only increased over the past few decades, but also is substantially higher than in other high-income countries.35 (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

What is behind this long-term decline in job quality? Researchers study a number of often interrelated phenomena. One line of research focuses on the rise of shareholder primacy, where corporate governance practices started to prioritize maximizing wealth for shareholders as the most important goal of publicly traded companies.36 Other research studies the effects of global trade liberalization, technological change, or domestic outsourcing.37 And some studies examine the racist backlash against the Civil Rights Act of 1964 or the erosion of U.S. labor market institutions such as the federal minimum wage as key drivers of rising inequality and the increasing prevalence of bad jobs.38

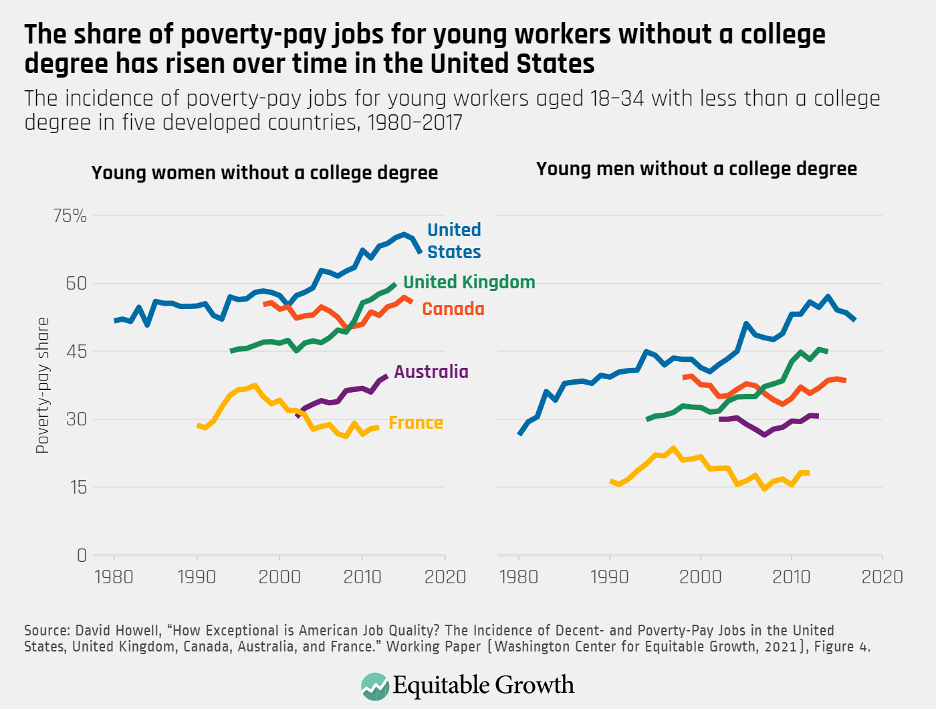

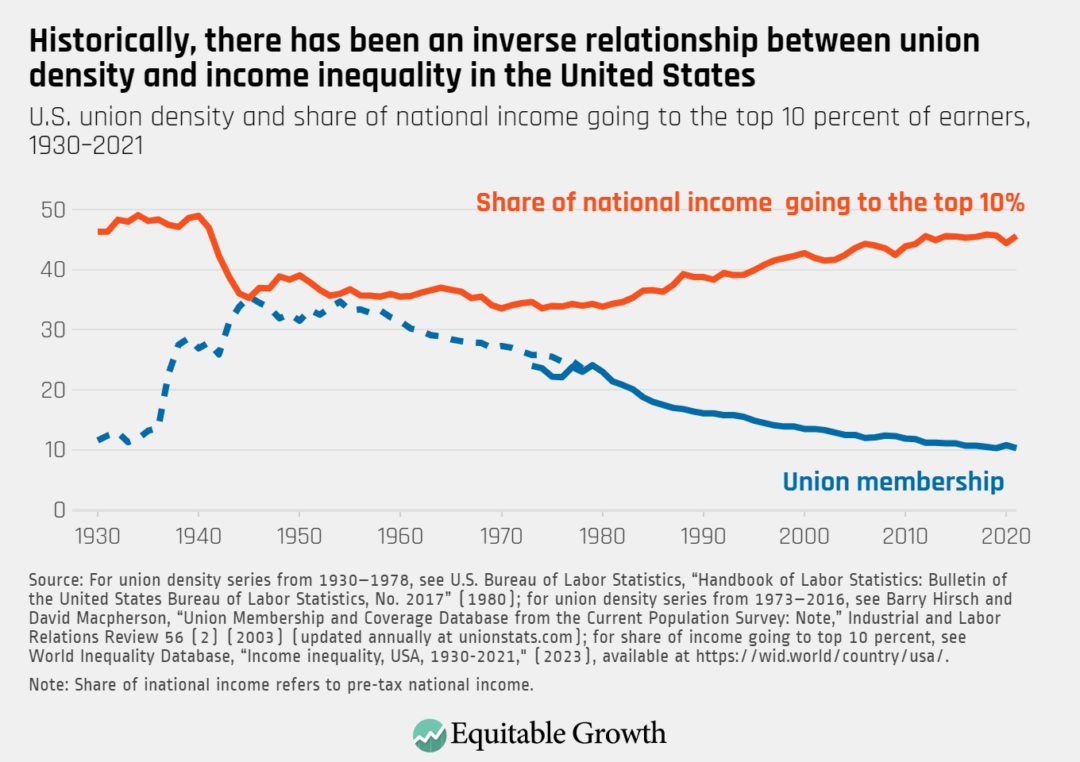

Several studies also highlight shifts in the industrial and occupational structure of the country, finding an explosion of care-giving and service-providing jobs at the lowest end of the wage distribution and a simultaneous decline in well-paying, goods-producing jobs.39 And yet another line of research focuses on the role of waning institutional support for organized labor and the long-term drop in the U.S. union membership rate—a decline that is explained, in part, by the falling share of employment of industries with relatively high union density such as manufacturing and construction.40 (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

The consequences of the coronavirus recession and subsequent U.S. economic recovery on measures of job quality

The COVID-19 pandemic triggered a short but sharp recession that brought about massive disruptions to workers and the broader U.S. economy. Between February and April of 2020, the unemployment rate skyrocketed from a 50-year low of 3.5 percent to a post-Depression high of almost 15 percent.41 More than 20 million workers were laid off or discharged in the span of those two months, with Black and Latina women suffering particularly deep employment losses.42 Especially for front-line and essential workers, working conditions deteriorated as many faced health risks, economic uncertainty, or had to perform new demanding tasks while on the job.

By mid-2022, however, U.S. employment had fully bounced back to its pre-pandemic levels—a much quicker rebound than the ones after the two previous recessions.43 Further, the exceptionally strong recovery in the labor market was followed by important gains for the lowest earners and a substantial increase in at least some measures of subjective job satisfaction.44

What powered these indications of higher job quality? Recent research by David Autor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Arindrajit Dube and Annie McGrew at the University of Massachusetts Amherst shows, for instance, that as job-switching rates and competition for labor increased after the initial pandemic shock, low-wage workers experienced especially fast real wage growth.45 And while pay inequality continues to be much greater than in the 1980s, the three co-authors find that these dynamics reversed about 25 percent of the four-decade increase in the gap between workers in the top 10 percent of the wage distribution and workers in the bottom 10 percent.

Even in the 5-to-10 years prior to the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, stronger wage growth toward the bottom of the wage distribution was leading to narrower earnings divides between the lowest and highest earners, though this gap seems to have either continued to increase or remained somewhat constant between those in the middle and those at the top of the U.S. wage ladder.46 Of the overall decline in earnings inequality, however, Clem Aeppli at Harvard University and Nathan Wilmers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology caution that “this source of inequality reduction is fragile with respect to the business cycle, and can only be expected to persist as long as labor markets are tight.”47

While there is evidence, then, that wage inequality fell or plateaued in recent years, these gains are likely to erode whenever the U.S. labor market weakens unless policymakers address the structural imbalance of power between workers and employers in the United States and provide greater institutional support for worker power.48

Worker power is a key component—and driver of—job quality

Strong unions and robust collective bargaining institutions deliver a number of positive outcomes for workers and the broader U.S. economy.49 Empirical evidence shows, for example, that unions raise wages for both union and nonunion members and lead to smaller racial and gender pay divides.50 Unions also are associated with non-wage aspects of job quality, with research finding that they contribute to the enforcement of labor standards, promote workplace safety, and foster norms of fairness both inside and outside the workplace.51

Research also finds that the high union membership rate of the mid-20th century helps explain an important chunk of the big decline in income inequality between the mid 1930s and late 1940s. And union membership has been found to foster solidarity and push back against racial resentment.52 A recent study even shows that organized workplaces can slow down the transmission of disease, with a team of researchers finding that the presence of unions was associated with 11 percent lower COVID-19 mortality rates among nursing home residents.53

But as union membership rates declined and collective bargaining institutions weakened over the course of the second half of the 20th century, organized labor became less effective at bargaining for good working conditions and pushing back against the imbalance of power between workers and employers.54 For instance, a paper by Jake Rosenfeld at Washington University in St. Louis shows that the positive relationship that existed between strikes and wages during the mid-20th century broke down around the early 1980s.55 This shift happened because the use of replacement hires by employers during strikes increased, the National Labor Relations Board and the U.S. Supreme Court began to reinterpret the NLRA in a way that was more favorable to businesses, and unions were less able to protect workers against employer retaliation.56

Other studies find that the union wage premium—the pay advantage that union members have vis-à-vis otherwise similar nonunion workers—seems to be declining in tandem with the long-term drop in union density.57 Changes to U.S. labor law contributed to the falling power of organized labor, with research finding that states that adopted “right-to-work” laws experienced a decrease in both union membership and in wages.58 And as union density fell and institutional support for organized labor weakened, so too did the equalizing power of unions.59 (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

By 2022, only 6 percent of private-sector wage and salary workers and 10.1 percent of all wage and salary workers in the United States were union members, the lowest rates on record.60 While a large share of U.S. workers report interest in being part of a union and public support for organized labor is the highest it’s been since the mid 1960s, employer hostility toward unions, lack of institutional support for workers, and labor laws that often fail to safeguard collective bargaining rights have all resulted in the erosion of worker power.61

Even as there have been important recent steps taken to support workers and buttress collective bargaining institutions—pro-worker efforts by the National Relations Board, measures that make it easier for federal employees to join a union, and provisions that aim to support “good-paying, union jobs” in key pieces of industrial policy legislation, for example—U.S. workers continue to face important obstacles when trying to organize, bargain collectively, and share in the gains from the economic value they create.62

Addressing these barriers would go a long way to ensuring industrial policies deliver on their potential to boost job quality in the United States.

Industrial policies will be much more effective in boosting job quality where there is institutional support for labor

There is no broad agreement on what policy interventions constitute industrial policy (just as there is not a single definition of what a good job is). A paper by researchers at the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development describes industrial policies as “interventions intended to improve structurally the performance of the domestic business sector.”63 A recent Congressional Research Service report defines industrial policy as “a comprehensive, deliberate, and more or less consistent set of government policies designed to change or maintain a particular pattern of production and trade within an economy.”64 And when Brian Deese was director of the National Economic Council, he described President Biden’s modern American industrial strategy as one that “uses public investment to crowd in more private investment, and make sure that the cumulative benefits of this investment strengthen our national bottom line.”65

Even though most discussions about industrial policy today focus on investments in infrastructure and manufacturing capacity, industrial policy also can be understood as any government intervention aimed at addressing market failures or improving the functioning of the domestic economy, with some scholars making the argument that the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 and minimum wage floors constitute industrial policy.66

For instance, Marc Linder at the University of Iowa argues that: “[a]lthough the minimum wage was obviously also designed to create microwelfare effects, its primary function lay in removing labor costs from competition, increasing productivity macroeconomically by driving “parasitic” firms out of business and concentrating production in the most competent firms, and in steering capital-labor relations.”67

But whatever its precise definition, there is a growing consensus that industrial policy is making a comeback in the United States. Indeed, as a key component of the Biden administration’s economic policy agenda, the federal government is currently deploying and attracting important investments to expand the country’s clean energy and transportation infrastructure, build more resilient supply chains, ensure the United States can produce key technologies, and create and support “good-paying, union jobs.”68

A number of recent government efforts and policy proposals leverage industrial policy to boost job quality

One mechanism through which the industrial policy laws enacted over the past two years can support good union jobs is by revitalizing the national industrial base.69

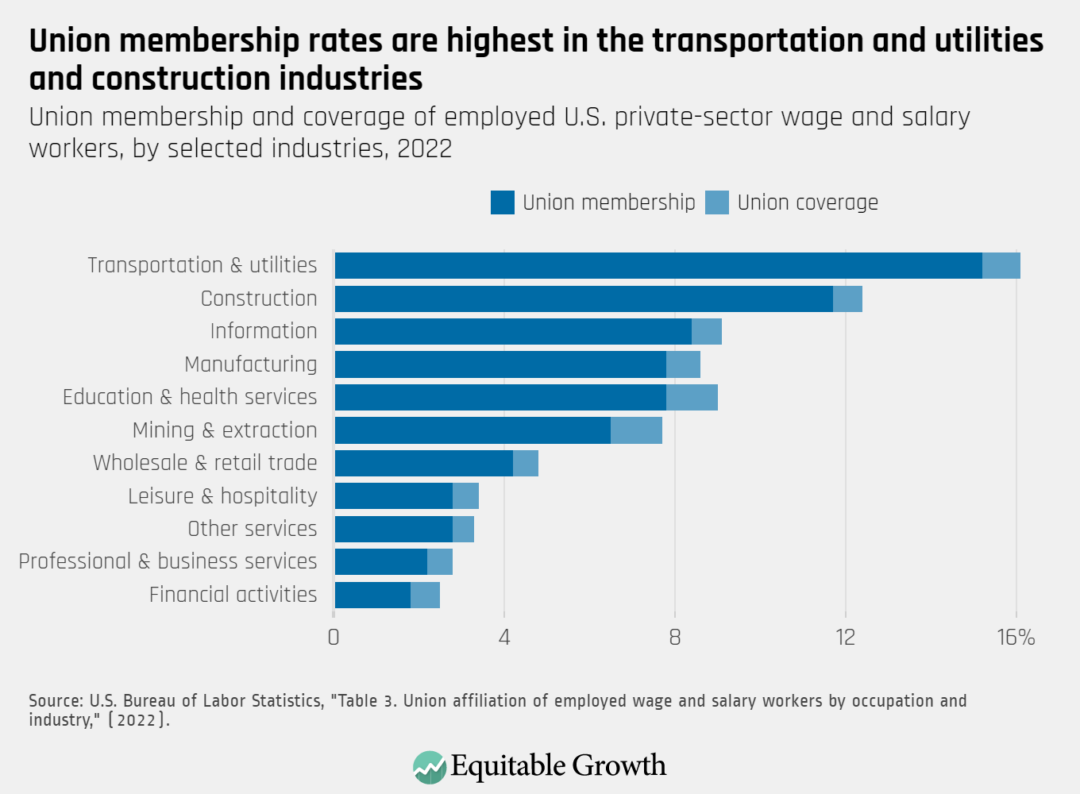

A large chunk of the roughly 9 million jobs the Inflation Reduction Act, for example, is expected to create over the next decade are likely going to be positions in manufacturing, transportation and utilities, and construction—parts of the U.S. economy that have relatively high union membership rates and that are still an important source of well-paying jobs for workers with lower levels of formal education, even as both union membership and job quality in those sectors deteriorated in the past few decades.70 (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

Similarly, the CHIPS and Science Act aims to increase the domestic manufacturing capacity of key technologies and create good employment opportunities in parts of the country that are especially likely to benefit from the construction of new plants and a boost in economic activity.71 The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act is projected to support millions of new jobs through investments in public transit, the building of roads and bridges, and electric and water infrastructure.72 And a number of ongoing government efforts aim to create high-quality jobs by establishing incentives and requirements that bolster demand for U.S-made products and materials such as steel and iron.73

A second mechanism through which the federal government is looking to improve job quality in the country is by attaching robust labor standards to industrial policy programs and projects.74 The majority of projects receiving funds under the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act have to meet prevailing wage requirements.75

Similarly, the Inflation Reduction Act includes enhanced tax credits and deductions for contractors and subcontractors of clean energy projects who pay prevailing wages.76 And under the CHIPS and Science Act, semiconductor manufacturers that apply for more than $150 million in subsidies are required to submit plans to make child care accessible to their facility and construction workers.77

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the CHIPS and Science Act, and the Inflation Reduction Act all include provisions to encourage or require the use of registered apprentices—workers who participate in U.S. Department of Labor-validated programs, earn wages, and learn new skills while on the job.78 And these three laws include requirements, incentives, and oversight mechanisms designed to ensure that the projects receiving government funding meet labor and equity standards and engage in high-road employment practices.79

A third way industrial policy investments can support good jobs is by increase the productive capacity of the U.S. workforce. Several scholars and government officials are making the case that industrial policies can create and support good employment opportunities by boosting labor productivity, including through workforce development programs. These kinds of programs can give workers “the skills and training to access newly created high-quality, unionized jobs in growing sectors,” argues a recent White House report.80 The idea, then, is that an industrial policy for good jobs should both foster an environment where firms supply more high-quality jobs and workers have the resources they need to meet employers’ demand for skills.81

What Dani Rodrik at Harvard University calls “productivism,” for instance, calls for government interventions such as traditional workforce development programs and the creation of an ARPA-W, an innovation program modeled after the Defense Advanced Research Project Agency that would create technologies to complement, rather than replace, workers’ labor.82

Industrial policies are less likely to be an effective vehicle to lift job quality if they are not accompanied by robust efforts to boost worker power

For these industrial policy efforts to improve working conditions and foster equitable economic growth effectively they need to be accompanied by steps to boost workers’ bargaining power more broadly. First, measures aimed at revitalizing the U.S. industrial base will be less likely to create good jobs without the presence of strong unions and institutional support for labor. Reshoring, domestic content requirements, and investments in clean energy infrastructure and semiconductor capacity, for instance, might not deliver the good, middle-wage manufacturing jobs so prevalent in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s if they are not accompanied by the robust labor laws and protections enacted before and during those during those decades.83

Indeed, while the U.S. manufacturing sector continues to represent an important source of good jobs for workers without a college degree, the sector no longer offers workers the advantages it did in the mid-20th century.84 A recent paper by economists at the U.S. Federal Reserve Board shows, for example, that the manufacturing wage premium—the additional pay that manufacturing workers used to receive vis-à-vis similar workers in other industries—disappeared in recent years largely because of the decline in union membership among manufacturing workers.85 Likewise, research by Rachel Dwyer at The Ohio State University and Erik Olin Wright at the University of Wisconsin-Madison finds that while the manufacturing sector experienced a small employment rebound in the 2010s, most of these job gains were low-paying positions.86

Productivity growth will be a less powerful mechanism to raise wages and drive better working conditions in the U.S. economy if workers do not also have access to the institutions and bargaining power that allows them to benefit from the economic value they create. For instance, research shows that these two labor market metrics rose in tandem between the 1940s and the 1960s, but starting in the early 1970s wage growth for the typical U.S. worker started to lag behind productivity growth—a decupling that is, at least in part, a result of the erosion of workers’ bargaining power.87

That U.S. workers’ pay has failed to keep up with the gains they have made in terms of labor productivity does not mean that the positive relationship between productivity growth and wage growth has completely broken down, or that current industrial policy investments will not create good jobs.88 It does mean, however, that efforts such as boosting innovation and creating incentives for workforce training might be weaker mechanisms to lift working conditions than during the decades when the relationship between productivity and pay was stronger.

Indeed, efforts aimed at bolstering labor productivity through workforce development programs and the introduction of new workplace technologies might not deliver high-quality jobs if U.S. workers do not have sufficient bargaining power and are not appropriately represented in the implementation of these initiatives. Suresh Naidu at Columbia University and Aaron Sojourner at the Upjohn Institute for Employment Research propose, for example, propose that under certain conditions these programs might even deepen income inequality.89

To that point, Naidu and Sojourner argue that in labor markets where there is outsized employer power, some training programs can result in employers capturing most if not all of the productivity gains from skills development, as well as “blunt worker incentives to search for something better.”90 Likewise, even so-called labor-friendly technologies can result in an erosion in job quality if they are deployed in a context of insufficient worker power.91

Evidence tends to find that labor standards included in industrial policy legislation improve working conditions

Labor law reform is perhaps the most powerful way to strengthen worker power in general and collective bargaining rights in particular.92 But the U.S. government has other tools to try to ensure that the employment opportunities created and supported by federal dollars pay fair wages and provide good working conditions.

Agencies that administer and implement programs created as part of industrial policy efforts, for example, can lift job quality by attaching conditions that prevent or discourage employers receiving federal funds from interfering with organizing efforts. This approach might already be working, with some reports that these requirements are translating into gains for workers.93

More broadly, the three most recent industrial policy laws—the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the Chips and Science Act, and the Inflation Reduction Act—include a number of provisions that aim to foster robust labor standards and promote high-road employment practices. Among them are:

- Prevailing wage standards

- Project labor agreements

- Registered apprenticeships

- Place-based policies

Below is a brief overview of each of these approaches to implementing industrial policies, analyzed with an eye toward understanding their value for boosting worker power and overall U.S. productivity.

Prevailing wage standards

At their most basic, prevailing wage laws set geographic and job-specific compensation floors for public work projects and projects that receive federal funding.94 By establishing minimum hourly wage rates and benefit levels, these laws aim to ensure public funds are not dragging down compensation in any given community, especially if large projects bring in contractors from areas that pay lower wages or offer fewer benefits.At the federal level, the Davis-Bacon and Related Acts and the McNamara-O’Hara Service Contract Act mandate that government contractors and subcontractors meeting certain criteria pay the local prevailing wages and benefits for specific job categories.95 In addition, more than half of U.S. states and several cities have their own prevailing wage laws.96

Academic evidence generally finds that prevailing wages promote worker safety and create incentives for employers to invest in worker training.97 Some studies find that prevailing wage laws substantially increase construction costs, but newer research tends to find no evidence of these negative effects.98 Rather, research finding that prevailing wages cause cost increases seems to fail to use the appropriate statistical controls.99

Some scholars also argue that prevailing wage standards exacerbate disparities between Black and White construction workers, since these standards disproportionately benefit workers who are members of construction unions—institutions with a history of racism and discrimination.100 The finding that prevailing wage standards contribute to racial disparities, however, is greatly contested. Recent evidence finds that Black workers in construction trades experience a greater wage premium from prevailing wages than White workers. Other research finds that prevailing wages result in greater racial disparities in labor market outcomes disappear once the appropriate statistical controls are applied.101

Project labor agreements

Project labor agreements are collective bargaining agreements between contractors and construction unions that aim to establish good working conditions and ensure that projects are completed efficiently and on time.102 Project labor agreements generally establish workers’ wage rates, overtime policies, and benefits. In addition, they often include provisions that set in place labor-dispute procedures, require contractors to hire workers locally or through union hiring halls, establish employment equity plans, and put in place no-strike and no-lockout clauses.

In 2009 President Obama signed an Executive Order encouraging federal agencies to consider using these agreements in large construction projects. And in 2022 President Biden singed an Executive Order that requires their use on federal projects of $35 million or more.103

Research examining the effects of project labor agreements is somewhat scarce, with the bulk of existing studies focusing on the effect these agreements have on project costs.104 A RAND Corporation study, for example, makes the case that requiring project labor agreements raised the cost and reduced the number of units constructed in a housing program in Los Angeles, since many developers avoided these agreements by proposing smaller projects that would not require an agreement.105 Indeed, critics of project labor agreements often argue they reduce competition by disincentivizing nonunion contractors from bidding on projects.

One report focusing on New York finds, however, finds that these agreements can lead to higher on-time and on-budget project completion rates, and are especially valuable when used for larger, longer, and more complicated projects since they provide certainty and standardized schedules, pay arrangements, and dispute resolution processes.106 Another study proposes that research finding that these agreements raise project costs often fail to apply adequate statistical controls.107 Further, this last analysis finds that project labor agreements are associated with greater workplace safety, equity, and high levels of satisfaction among the different stakeholders.108

Registered apprenticeships

Usually a combination of paid on-the-job training with classroom courses, the goal of apprenticeships is to develop skills, create pathways for upward career mobility, and boost workers’ productivity. Many forms of apprenticeships and workforce development exist in the United States, but one of the biggest and most important ones flows from the 1937 National Apprenticeship Act, which established the Registered Apprenticeship Program.109

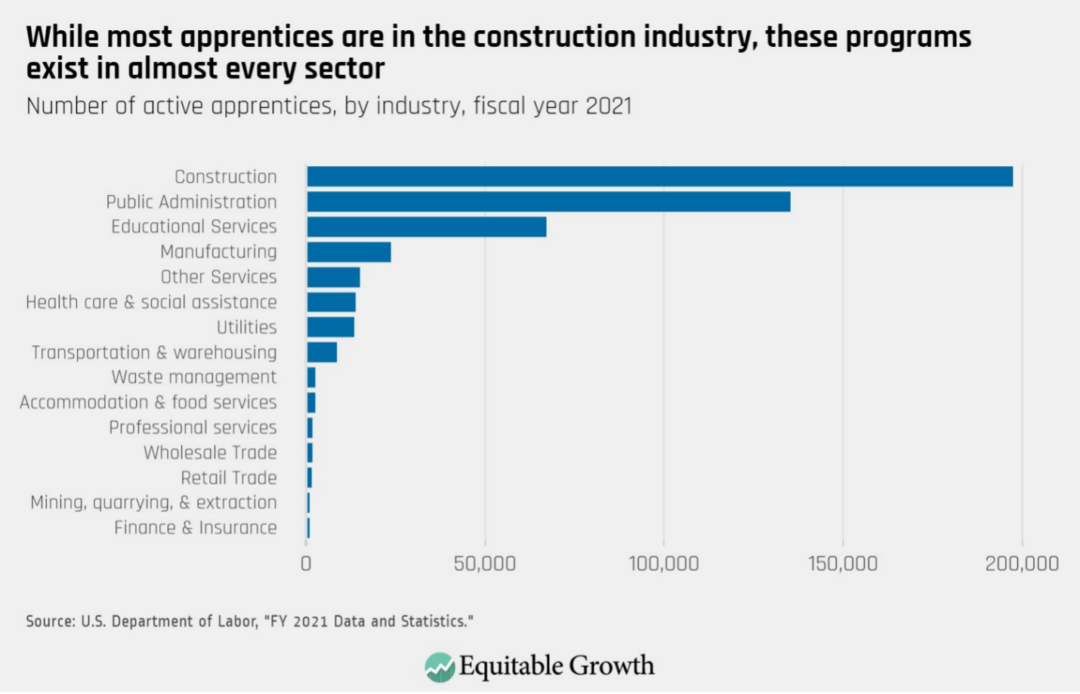

The Registered Apprenticeship program requires that employers, groups of employers, or joint union-employer groups act as sponsors and meet certain standards for their apprenticeships to be recognized by the U.S. Department of Labor. These requirements include guaranteeing that apprentices receive supervised training, wage increases that match the learning of new skills, and compliance with the Equal Employment Opportunity Act.110 Employers can pay apprentices less than the prevailing wage rate, and the federal government offers a number of grants and tax incentives for employers who use registered apprenticeships.111 While the bulk of apprenticeships take place in the construction and manufacturing industries, sectors such as healthcare and information technology also have apprentices.112 (See Figure 5.)

Figure 5

Available research tends to find that registered apprenticeships lead to higher worker earnings, higher worker retention rates, greater worker productivity, and better firm performance.113 There also is evidence that the returns workers receive from apprenticeships are substantially greater than the returns they receive from other forms of training, such as two-year community college programs.114 Employers also value these programs, with a 2007 survey showing that 97 percent of sponsors would recommend registered apprenticeships.115 Yet the share of U.S. workers who participate in apprenticeships is substantially smaller than in peer countries.116

One barrier to wider participation of employers in apprenticeship programs is that employers are often reluctant to invest in apprenticeships and training in a context of high rates of turnover. Further, unlike countries with more institutionalized apprenticeship systems such as Austria and Germany, in the United States apprenticeships are often designed and created by individual employers, who are less likely to have the know-how to navigate the registration process and maintain compliance.117 All in all, as a share of their GDP, countries such as Austria, Finland, Denmark, and France all spend more than four times as much as the United States on worker training.118

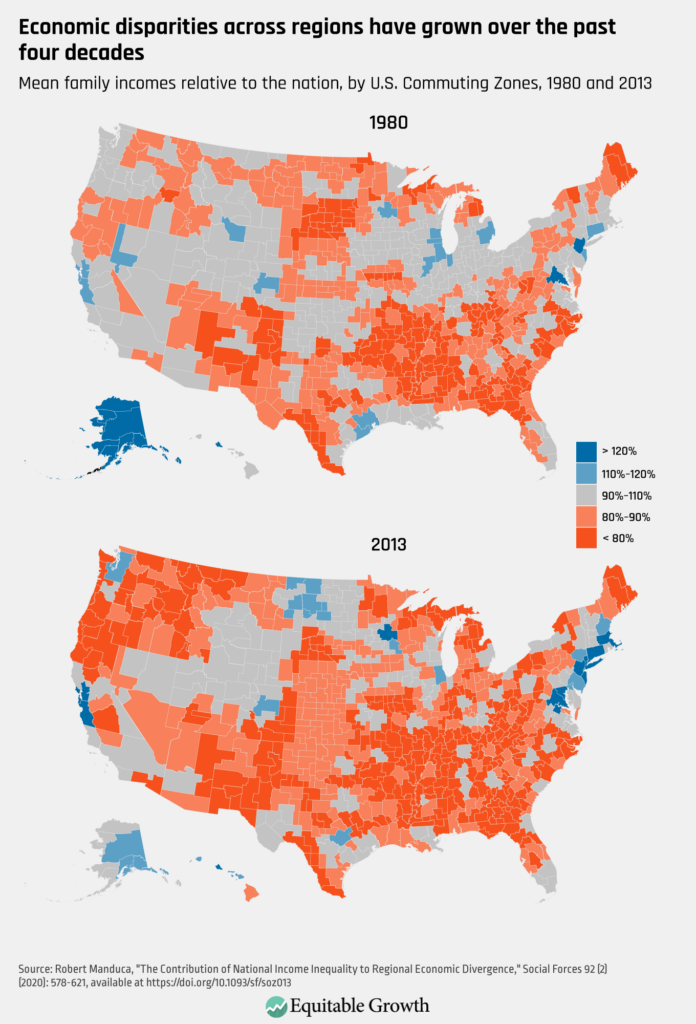

Placed-based policies

Broadly, place-based policies are government efforts aimed at improving the economic performance of a given area.119 They can be deployed through a number of mechanisms, including tax incentives for businesses, the creation of enterprise zones, customized job trainings, grants, and infrastructure investments. Place-based policies often have the objective of sparking economic activity in parts of the country that are underperforming, as well as of tempering deep regional disparities within the United States.120 (See Figure 6.)

Figure 6

The Tennessee Valley Authority is an important early example.121 More recently, as part of the American Rescue Plan of 2021, the U.S. Economic Development Administration launched the Good Jobs Challenge—awarding funds to workforce training partnerships that look to “solve for local talent needs and increase the supply of trained workers and help workers secure jobs in 15 key industries that are essential to U.S. supply chains, global competitiveness, and regional development.”122

What does research find about the effectiveness of these measures? A review of the economics literature by economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco finds that some place-based policies tend to be more successful than others.123 The authors find, for example, that economic enterprise zones do not seem to increase employment or reduce poverty, but they do seem to increase housing prices—a finding consistent with other analyzes showing that enterprise zones tend to be regressive.124

Yet place-based infrastructure investments and targeted subsidies do tend to have positive effects on employment and productivity. In a recent paper, for example, Timothy Bartik at W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research proposes that even though place-based policies can be expensive, they lead to substantial job gains and lead to better outcomes if they are deployed in distressed areas and in the form of public services to businesses rather than as tax incentives.125 Similarly, economists at Harvard University propose that employment subsidies are more effective in parts of the country where employment rates are relatively low to begin with.126

Prevailing wages, project labor agreements, registered apprenticeships, and place-based policies are, in some way or another, embedded in the industrial policy laws enacted over the past two years. Along with efforts to boost worker power, the effective implementation of these and other requirements, rules, incentives, and programs represent a historic opportunity for policymakers to ensure that federal dollars deployed through the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the CHIPS and Science Act, and the Inflation Reduction Act support good jobs.

Boosting workers’ bargaining power in a new industrial policy era

Industrial policies are expected to create millions of new jobs. Researchers at the Political Economy Research Institute of the University of Massachusetts Amherst estimate that the Inflation Reduction Act will create about 912,000 jobs per year over the course of a decade, with especially important gains through electricity, building, manufacturing, environmental justice and community resilience, land, and agricultural programs.127 The CHIPS and Science Act investments are projected to create about 1.1 million jobs by 2026.128 And the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act is expected to create somewhere between 883,000 and 2 million jobs per year through 2030.129

The extent to which these jobs will offer good wages and high-quality working conditions will depend on a number of factors, among them:

- Support workers’ bargaining power through enforcement of labor standards and accountability

- Increase workers’ bargaining power across entire sectors

- Increase workers’ bargaining power across the U.S. labor market

All three of these factors are necessary for this new industrial policy era in the United States to take hold in order to create more equitable economic growth that in turn is stronger and sustainable well in the first half of the 21st century. So let’s review each of them in turn.

Policy interventions to support workers’ bargaining power through enforcement of labor standards and accountability

First, policymakers must ensure the implementation of robust enforcement and accountability mechanisms to ensure that recipients of government funds comply with the labor standards embedded in industrial policy legislation, such as prevailing wage requirements. Policymakers must also ensure that investments reach and benefit the workers and communities who need them most through robust outreach, technical assistance, and support.

Timely and robust analysis of these investments will be critical, both in the near term and the long term. Also key will be for government agencies and researchers to have access to adequate data and data infrastructure. This data also will be important for policymakers as they consider how to design future investments. Targeted and ongoing communications with and feedback from workers and worker-led organizations are also important for the implementation of policies.

To support organized labor, there are recent examples of how the implementation and administration of industrial policy investments can protect collective bargaining rights. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, for instance, prohibits manufacturers participating in its Clean School Bus Program from using rebate funds to prevent workers from organizing.130 In the spring of 2023, workers at a factory in Georgia used the rule to call out anti-union tactics by their employer and as part of their ultimately successful organizing campaign.131

Likewise, the Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment program, which is administered by the U.S. Department of Commerce and sets the conditions for more than $42 billion in funds allocated by Congress in the Infrastructure Investment and jobs Act for broadband infrastructure, requires that grant applicants disclose their history of compliance with federal employment and labor law and create plans with commitments to labor standards.132 These plans include commitments to prevent the misclassification of workers as independent contractors and union neutrality.133 Similarly, the CHIPS Incentives program administered by the U.S. Department of Commerce strongly encourages the use of project labor agreements in construction projects.134

Policy interventions to increase workers’ bargaining power across entire sectors

Policymakers should consider leveraging the coordinating power of the government to establish good working conditions across entire industries. Indeed, research shows that sectoral bargaining, wage boards, and sectoral employment programs would deliver gains for workers and the entire U.S. labor market.

Collective bargaining in the United States generally happens at the firm-level, which often leads to tensions between workers and employers because unionization is generally perceived by businesses as a driver of higher labor costs and therefore a disadvantage vis-à-vis competitors with nonunionized workforces.135 Widespread practices such as domestic outsourcing and workplace fissuring also make firm-level collective bargaining harder, since subcontracting arrangements limit workers’ ability to bargain with the firms that have control over their working conditions.136

In contrast, a system of sectoral bargaining where workers are also able bargain at the level of the industry or sector would lead to greater collective bargaining coverage and presents a powerful opportunity to lift labor standards for more U.S. workers.137

Similarly, research shows that wage boards—governmental bodies that usually include representatives from labor, business, and the general public who establish minimum pay for entire industries or occupations—would not only increase pay at the bottom of the U.S. income ladder but also would lead to substantial wage gains for middle-wage workers.138

Likewise, a report by economists Suresh Naidu and Aaron Sojourner for the Roosevelt Institute finds that sectoral employment programs have the potential to result in more significant gains for workers, and might be particularly effective if they partner with unions as is the case of the Wisconsin Regional Training Partnership.139 Existing sectoral programs usually include representatives from businesses and workers, identify industrywide needs, and provide services such as job search assistance, employer matching, and retention coaching—services that benefit employers and can result in higher returns to workers.

Policy interventions to increase workers’ bargaining power across the entire U.S. labor market

More broadly, many of the steps needed to ensure that industrial policies result in the creation of good jobs are the same policy interventions needed to increase worker power across the entire U.S. labor market. These measures include continuing to increase the capacity and resources of the National Labor Relations Board so that it can more effectively protect workers against illegal employment practices and safeguard collective bargaining rights.140 They also include reforms to U.S. labor law so that workers are better protected against unfair and illegal employment practices, among them policies to:

- Prevent employers from misclassifying workers as independent contractors141

- Extend collective bargaining rights to workers that are not currently covered by the National Labor Relations Act142

- Allow workers to bargain with the firms that have control over their working conditions even if they are not directly employed by those firms143

- Clarify protections around workers’ right to strike144

Strengthening the U.S system of income supports would also deliver better outcomes for workers and boost their standing in the labor market.145 Research finds, for instance, that more generous Unemployment Insurance benefits give workers the time and financial security needed to find jobs that are a better match for their interests and skills, leading to more productive employer-worker matches and to a better functioning of the labor market as a whole.146 A higher federal minimum wage also would go a long way toward improving workers’ bargaining power, increasing the earnings of low earners, and narrowing racial wage divides after being stuck at $7.25 since 2009.147

Conclusion

Over the past decade or so U.S. workers experienced an overall reduction in earnings inequality, with gains for workers at the bottom of the wage distribution explaining most if not all of this decline. In addition, the robust and quick policy response to the COVID-19 health and economic crises resulted in an exceptionally strong recovery in employment, with a tight U.S. labor market delivering further gains for workers. Yet available evidence finds that these gains are fragile and contingent on the strength of the U.S. labor market, since public policy has yet to address the structural imbalance of power between workers and employers.148

This means that institutional support for U.S. workers and strong collective bargaining rights will be essential for both continuing to see improvements in workers’ labor market outcomes and for ensuring President Biden’s industrial policies deliver on their promise to support millions of good union jobs.

Ultimately, some of the most effective measures to ensure that the jobs created through industrial policies are good jobs are the same measures needed to boost job quality throughout the entire economy: labor law reform and other efforts to boost worker power, including strengthening the system of income supports and raising the federal minimum wage. Labor standards and measures that encourage high-road employment practices in projects receiving federal funding also will be key, with effective mechanisms to enforce and monitor compliance playing an essential role.

Investments in industrial policies present a historic opportunity to lift job quality, drive innovation, and foster broadly shared economic growth, but these efforts will be much more effective if they are paired with steps to boost worker power across the United States.

About the author

Carmen Sanchez Cumming is a research associate at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth. Prior to joining Equitable Growth, Sanchez Cumming was a campaigns assistant at Oxfam America and research assistant at Middlebury College’s Department of Sociology. Her interests are in labor market policy, wage inequality, and market concentration. Sanchez Cumming holds a B.A. in economics and sociology from Middlebury College. In the fall of 2023, she will enter the Master in Public Policy program at the University of California, Berkeley.

End Notes

1. Todd Tucker and Stephen Sterling, “Industrial policy and planning: A new (old) approach to policymaking for a new era” (Washington: Roosevelt Institute, 2021), available at https://rooseveltinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/RI_ANewOldApproachtoPolicymakingforaNewEra_IssueBrief_202108.pdf.

2. “Remarks on executing a modern American industrial strategy by NEC director Brian Deese,” (White House, 2022), available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2022/10/13/remarks-on-executing-a-modern-american-industrial-strategy-by-nec-director-brian-deese/.

3. “Fact sheet: The Inflation Reduction Act supports workers and families,” (White House, 2022), available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/08/19/fact-sheet-the-inflation-reduction-act-supports-workers-and-families/. See also “Biden-Harris administration roadmap to support good jobs,” (White House, 2023), available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/05/16/biden-harris-administration-roadmap-to-support-good-jobs/.

4. Bluegreen Alliance, “A user guide to the Inflation Reduction Act: How new investments will deliver good jobs, climate action, and health benefits,” (2023), available at https://www.bluegreenalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/BGA-IRA-User-Guide-Print-FINAL-Web.pdf.

5. Christopher Thomas, “A semiconductor strategy for the United States,” (Washington: The Brookings Institution, 2022), available at https://www.brookings.edu/research/a-semiconductor-strategy-for-the-united-states/. See also “FACT SHEET: CHIPS and Science Act Will Lower Costs, Create Jobs, Strengthen Supply Chains, and Counter China,: (White House, 2022), available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/08/09/fact-sheet-chips-and-science-act-will-lower-costs-create-jobs-strengthen-supply-chains-and-counter-china/.

6. Michelle Holder and Shaun Harrison, “Why the Infrastructure and Jobs Act is good economics,” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2022), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/why-the-infrastructure-investment-and-jobs-act-is-good-economics/.

7. Patrick Kline and Enrico Moretti, “Local economic development, agglomeration economics, and the big push: 100 years of evidence from the Tennessee Valley Authority,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 129 (1)(2014): 275–331, available at https://academic.oup.com/qje/article-abstract/129/1/275/1899702. See also Lawrence Mishel, Lynn Rhinehart, and Lane Windham, “Explaining the erosion of private-sector unions: How corporate practices and legal changes have undercut the ability of workers to organize and bargain,” (Washington: Economic Policy Institute, 2020), available at https://www.epi.org/unequalpower/publications/private-sector-unions-corporate-legal-erosion/.

8. Kimberly Bayard, Tomaz Cajner, Vivi Gregorich, and Maria Tito, “Are manufacturing jobs still good jobs? An exploration of the manufacturing wage premium,” Finance and economics discussion series, (Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 2022), available at https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/feds/files/2022011pap.pdf

9. Jake Rosenfeld, “Desperate measures: Strikes and wages in post-Accord America,” Social Forces 85 (1)(2006): 235–265, available at https://academic.oup.com/sf/article-abstract/85/1/235/2234993.

10. David Cooper and Lawrence Mishel, “Collective bargaining’s erosion expanded the pay-productivity gap,” https://www.epi.org/publication/collective-bargainings-erosion-expanded-the-productivity-pay-gap-2/. See also Michael Wachter, “The striking success of the National Labor Relations Act,” Faculty Scholarship at Penn Carey Law, (2012): 424–462, available at https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1492&context=faculty_scholarship. See also Henry Faber and others, “Unions and inequality over the twentieth century: new evidence from survey data” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 163 (3)(2021): 1325–1385, available at https://academic.oup.com/qje/article/136/3/1325/6219103.

11. Lawrence Mishel, Lynn Rhinehart, Lane Windham, “Explaining the erosion of private-sector unions: How corporate practices and legal changes have undercut the ability of workers to organize and bargain.”

12. Nicole Fortin, Thomas Lemieux, and Neil Lloyd “Right-to-Work laws, unionization, and wage setting.” Working Paper 30098 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2022), available at https://www.nber.org/papers/w30098. See also Paul Secunda, “The Contemporary ‘First inside the velvet glove’: Employer captive audience meetings under the NLRA,” Labor: Public Policy & Regulation eJournal (2010), available at https://ecollections.law.fiu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1103&context=lawreview. See also Kate Bronfenbrenner, “No holds barred – the intensification of employer opposition to organizing” (Washington: Economic Policy Institute, 2009), available at https://www.epi.org/publication/bp235/.

13. Wilma Liebman, “Decline and Disenchantment: Reflections on the Aging of the National Labor Relations Board,” Berkeley Journal of Employment and Labor Law 28 (2)(2007): 569–89, available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/24052247 . See also Kathryn Zickuhr and Carmen Sanchez Cumming, “Labor Day: Labor Standards and institutional support for collective action are essential for an equitable U.S. economy,” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, September 4, 2020), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/labor-day-labor-standards-and-institutional-support-for-collective-action-are-essential-for-an-equitable-u-s-economy/nlrb-figure/. See also Mark Stelzner, “The new American way—how changes in labour law are increasing inequality,” Industrial Relations Journal 48 (3)(2017): 231– 255, available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/irj.12177.

14. Kate Bronfenbrenner, “No holds barred—the intensification of employer opposition to organizing.” See also Jake Rosenfeld, What unions no longer do, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014), available at https://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674725119.

15. Kate Bahn and Corey Husak, “Factsheet: The PRO Act addresses income inequality by boosting the organizing power of U.S. workers,” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, February 6, 2020), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/factsheet-the-pro-act-addresses-income-inequality-by-boosting-the-organizing-power-of-u-s-workers/.

16. International Labour Organization, “Measuring job quality: difficult but necessary,” January 27, 2020, available at https://ilostat.ilo.org/measuring-job-quality-difficult-but-necessary/.

17. Ali Mohammad Mosadeghrad, Ewan Ferlie, and Duska Rosenberg, “A study of relationship between job stress, quality of working life and turnover intention among hospital employees” Health Services Management Research 24 (4)(2011):170-181, available at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1258/hsmr.2011.011009?journalCode=hsma. See also Maaike van der Noordt and others, “Health effects of employment: a systematic review of prospective studies” Occupational and Environmental Medicine (71)(2014):730-736, available at https://oem.bmj.com/content/71/10/730.short. See also Trevor Peckham and others, “Evaluating Employment Quality as a Determinant of Health in a Changing Labor Market,” RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 5(4)(2019):258–281, available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6756794/. See also Daniel Schneider and Kristen Harknett, “It’s about time: How work schedule instability matters for workers, families, and racial inequality,” The Shift Project, available at https://shift.hks.harvard.edu/its-about-time-how-work-schedule-instability-matters-for-workers-families-and-racial-inequality/. See also Faith Karahan, Serdar Ozkan, and Jae Song, “Anatomy of lifetime earnings inequality: Heterogeneity in job ladder risk vs human capital.” Working Paper no. 2022-22 (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 2022), available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4006858.

18. Saija Mauno, Ting Cheng, and Vivian Lim, “The Far-reaching consequences of job insecurity: A review on family-related outcomes,” Marriage and family review 53 (8)(2017): 717–743, available at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01494929.2017.1283382.

19. Kate Bahn and Carmen Sanchez Cumming, “Improving U.S. labor standards and the quality of jobs to reduce the cost of employee turnover to U.S. companies,” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2020), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/improving-u-s-labor-standards-and-the-quality-of-jobs-to-reduce-the-costs-of-employee-turnover-to-u-s-companies/.

20. Mario Pianta and Jelena Reljic, “The good jobs-high innovation virtuous cycle,” Economia Politica (39)(2022): 783–811, available at https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40888-022-00268-6#Sec11.

21. Zeynep Ton, “Why ‘good jobs’ are good for retailers,” Harvard Business Review, January-February, 2012, available at https://hbr.org/2012/01/why-good-jobs-are-good-for-retailers.

22. Anne Saint-Martin, Hande Inanc, and Christopher Prinz, “Job Quality, Health and Productivity: An evidence-based framework for analysis,” OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, (Paris, 2018), available at https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/paper/a8c84d91-en.

23. Chang-Tai Hsieh and others, “The allocation of talent and U.S. economic growth,” Econometrica 87 (5)(2019), available at https://www.econometricsociety.org/publications/econometrica/2019/09/01/allocation-talent-and-us-economic-growth.

24. See Almarina Gramozi, Theodore Palivos, and Marios Zachariadis, “On the degree and consequences of talent misallocation for the United States,” University of Cyprus Working Papers in Economics (2020), available at https://ideas.repec.org/p/ucy/cypeua/09-2020.html. See also Lisa Cook and Jan Gerson, “The implications of U.S. gender and racial disparities in income and wealth inequality at each stage of the innovation process,” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2019), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/072519-innovation-inequal-ib.pdf.

25. David Howell and Arne Kalleberg, “Declining job quality in the United States: Explanations and evidence,” RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the social sciences, 5(4)(2019): 1–53, available at https://www.rsfjournal.org/content/5/4/1. See also David Howell, “From decent to lousy jobs: New evidence on the decline in American job quality, 1979–2017.” Working paper (Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2019), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/working-papers/from-decent-to-lousy-jobs-new-evidence-on-the-decline-in-american-job-quality-1979-2017/. See also Drew Desilver, “For most U.S. workers have barely budged in decades,” Pew Research Center, August 7, 2018, available at https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2018/08/07/for-most-us-workers-real-wages-have-barely-budged-for-decades/.

26. Elise Gould, “State of working America wages 2019,” (Economic Policy Institute, February 20, 2020), available at https://www.epi.org/publication/swa-wages-2019/. See also John Schmitt, “Low-wage lessons,” (Washington: Center for Economic and Policy Research, 2012), available at https://www.cepr.net/documents/publications/low-wage-2012-01.pdf.

27. Leonard Greenhalgh and Zehava Rosenblatt, “Evolution of research on job insecurity,” International Studies of Management and Organization 20 (1)(2020): 6-19, available at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.2753/IMO0020-8825400101. See also Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez, “Income and wage inequality in the united states, 1913-2002.” In A.B. Atkinson and Thomas Piketty, ed., Top incomes over the 20th century: A contrast between Continental European and English-speaking countries, (Oxford, 2007), available at https://wid.world/document/piketty-thomas-and-saez-emmanuel-2007-income-and-wage-inequality-in-the-united-states-1913-2002-in-atkinson-a-b-and-piketty-t-editors-top-incomes-over-the-twentieth-century-a-contra/.

28. Lawrence Mishel and Jori Kandra, “Wages for the top 1% skyrocketed 160% since 1979 while the share of wages for the bottom 90% shrunk,” (Washington: Economic Policy Institute, December 1, 2020), available at https://www.epi.org/blog/wages-for-the-top-1-skyrocketed-160-since-1979-while-the-share-of-wages-for-the-bottom-90-shrunk-time-to-remake-wage-pattern-with-economic-policies-that-generate-robust-wage-growth-for-vast-majority/.

29. Congressional Research Service, “Real wage trends, 1979 to 2019,” December 28, 2020, available at https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R45090.pdf.

30. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Average Hourly Earnings of Production and Nonsupervisory Employees, Total Private [AHETPI]”, retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, available at https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=ozZ. See also U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Average Hourly Earnings of Production and Nonsupervisory Employees, Total Private [AHETPI]”, retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, available at https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=qa1U.

31. Bruce Sacerdote, “Fifty years of growth in American Consumption, Income, and wages.” Working Paper no.23292 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2023), available at https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w23292/revisions/w23292.rev0.pdf.

32. University at Buffalo School of Management, “U.S. private sector Job Quality Index (JQI),” available at https://ubwp.buffalo.edu/job-quality-index-jqi/.

33. David Howell, “From decent to lousy jobs: New evidence on the decline in American job quality, 1979–2017,” available at https://equitablegrowth.org/working-papers/from-decent-to-lousy-jobs-new-evidence-on-the-decline-in-american-job-quality-1979-2017/.

34. Kathryn Zickuhr, “Worker power and pay quality for young workers without a college degree in the United States,” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, December 9, 2021), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/worker-power-and-pay-quality-for-young-workers-without-a-college-degree-in-the-united-states/.

35. Ibid. The poverty-wage threshold (referred to as the “lousy-wage” threshold in Howell’s 2019 working paper) is defined as two-thirds of the median wage for full-time workers, the conventional low-wage definition used by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Poverty-pay jobs are those that are paid below the poverty-wage threshold or those in which the worker is employed part-time involuntarily. The inclusion of involuntary part-time workers also distinguishes the poverty-pay definition from typical low-wage definitions by capturing a worker’s overall earnings adequacy, instead of only wage levels.

36. Kate Bahn and Carmen Sanchez Cumming, “How corporate governance strategies hurt worker power in the United States,” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, September 6, 2022), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/how-corporate-governance-strategies-hurt-worker-power-in-the-united-states/

37. Dani Rodrik, “A primer on trade and inequality,” (2021), available at https://drodrik.scholar.harvard.edu/files/dani-rodrik/files/a_primer_on_trade_and_inequality.pdf. See also David Autor, Lawrence Katz, and Alan Krueger, “Computing Inequality: Have computers changed the labor market?,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 113(4)(1998): 1169-1213, available at https://academic.oup.com/qje/article-abstract/113/4/1169/1917014. See also Kate Bahn, “Research finds the domestic outsourcing of jobs leads to declining U.S. job quality and lower wages,” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, August 21, 2019), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/research-finds-the-domestic-outsourcing-of-jobs-leads-to-declining-u-s-job-quality-and-lower-wages/.

38. Erin Wolcott, “Did racist labor policies reverse equality gains for everyone,” available at https://erinwolcott-econ.github.io/Wolcott_RacistLaborPolicies.pdf. See also Kate Bahn and Will McGrew, “Factsheet: Minimum wage increases are good for U.S. workers and the U.S. economy,” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, July 8, 2019), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/factsheet-minimum-wage-increases-are-good-for-u-s-workers-and-the-u-s-economy/.

39. Rachel Dwyer, “The care economy? Gender, economic restructuring, and job polarization in the U.S. labor market,” American Sociological Review 78 (3)(2013), available at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0003122413487197. See also Rachel Dwyer and Erik Olin Wright, “Low-wage job growth, polarization, and the limits and opportunities of the service economy,” RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 5 (4)(2019):56-76, available at https://www.rsfjournal.org/content/5/4/56.abstract. See also Harry Holzer, “Job market polarization and U.S. worker skills: A tale of two middles,” (Washington: The Brookings Institution, 2015), available at https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/polarization_jobs_policy_holzer.pdf.

40. Mark Paul and Mark Stelzner, “Rethinking collective action and U.S. labor laws in a monopsonistic economy,” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, December 20, 2018), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/rethinking-collective-action-and-u-s-labor-laws-in-a-monopsonistic-economy/. See also Henry Faber and others, “Unions and inequality over the twentieth century: new evidence from survey,” available at https://academic.oup.com/qje/article/136/3/1325/6219103.

41. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Unemployment Rate [UNRATE],” retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, available at https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/UNRATE.

42. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Layoffs and Discharges: Total Nonfarm [JTSLDL],” retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, available at https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/JTSLDL. See also Kate Bahn and Carmen Sanchez Cumming, “jobs report: a year into the coronavirus recession, employment losses have been greatest for Black women workers and Latinx workers,” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, March 5, 2021), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/jobs-report-a-year-into-the-coronavirus-recession-employment-losses-have-been-greatest-for-black-women-workers-and-latinx-workers/.

43. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “All Employees, Total Nonfarm [PAYEMS],” retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, available at https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/PAYEMS.

44. Lauren Weber, “Workers are happier than they’ve been in decades,” The Wall Street Journal, May 11, 2023, available at https://www.wsj.com/articles/workers-job-satisfaction-survey-c42addba.

45. David Autor, Arindrajit Dube, and Annie McGrew, “The unexpected compression: Competition at work in the low wage labor market.” Working paper no.31010 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2023), available at https://www.nber.org/papers/w31010. See also Carmen Sanchez Cumming, “Ahead of new jobs data releases, here’s what employment growth and job switching mean for wage disparities in the U.S. labor market,” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, March 7, 2023), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/ahead-of-new-u-s-jobs-data-releases-heres-what-employment-growth-and-job-switching-mean-for-wage-disparities-in-the-u-s-labor-market/.

46. Matthew Dey, “Were wages converging during the 2010s expansion?,” Monthly Labor Review, June 2022, available at https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2022/article/were-wages-converging-during-the-2010s-expansion.htm. See also Clem Aeppli and Nathan Wilmers, “Rapid wage growth at the bottom has offset rising U.S. inequality,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 119 (42)(2022), available at https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2204305119.

47. Ibid.

48. Kate Bahn, “’Clean Slate for worker power’ promotes a fair and inclusive U.S. economy,” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, January 29, 2020), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/clean-slate-for-worker-power-promotes-a-fair-and-inclusive-u-s-economy/.

49. Paul Gabriel and Susan Schmitz, “A longitudinal analysis of the union wage premium for U.S. workers,” Applied Economics Letters 21 (7)(2014): 487–489, available at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13504851.2013.868583. See also Patrick Denice and Jake Rosenfeld, “Unions and nonunion pay in the United States, 1977–2015,” Sociological Science 23 (5)(2018), available at https://sociologicalscience.com/articles-v5-23-541/.

50. Cherrie Bucknor, “Black workers, unions, and inequality,” (Washington: Center for Economic Policy Research, 2016), available at https://www.cepr.net/report/black-workers-unions-and-inequality/. See also Elise Gould and Celine McNicholas, “Unions help narrow the gender wage gap,” (Economic Policy Institute, 2017), available at https://policycommons.net/artifacts/1407587/unions-help-narrow-the-gender-wage-gap/2021850/.

51. Ioana Marinescu, Yue Qiu, and Aaron Sojourner, “Wage inequality and labor rights violations,” (Social Science Research Network, 2022), available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3673495. See also Aaron Sojourner, “Effects of union certification on workplace-safety enforcement: Regression-discontinuity evidence,” ILR Review, 75 (2)(2022): 373–401, available at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0019793920953089?journalCode=ilra. See also Bruce Western and Jake Rosenfeld, “Unions, norms, and the rise in U.S. wage inequality,” American Sociological Review 76 (4)(2011): 513-537, available at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0003122411414817?journalCode=asra.

52. Henry Farber and others, “Unions and inequality over the twentieth century: New evidence from survey data.” See also Kate Bahn and Carmen Sanchez Cumming, “Labor Day: How unions promote racial solidarity in the United States,” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, September 2, 2021), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/labor-day-how-unions-promote-racial-solidarity-in-the-united-states/. See also Paul Frymer and Jake Grumbach, “Labor unions and white racial politics,” American Journal of Political Science 65 (1)(2021): 225–240, available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/ajps.12537.

53. Adam Dean, Jamie McCallum, Atheendar Venkataramani, “Unions in the United States improve worker safety and lower health inequality,” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2022), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/research-paper/unions-in-the-united-states-improve-worker-safety-and-lower-health-inequality/.

54. Jake Rosenfeld, “What unions no longer do.”

55. Jake Rosenfeld, “Desperate measures: Strikes and wages in post-accord America.”

56. Mark Stelzner, “The new American way—how changes in labour law are increasing inequality.” See also Joseph McCartin, “The PATCO strike and the decline of labor,” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History 31 (2021), available at (https://oxfordre.com/americanhistory/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.001.0001/acrefore-9780199329175-e-867;jsessionid=D446F9323159812381CD51A6F8F74795.

57. David Blanchflower and Alex Bryson, “What effects do unions have on wages and would Freeman and Medoff be surprised?” Journal of Labor Research 25 (2004):384-414, available at https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12122-004-1022-9. See also Tony Fang and John Hartley, “Evolution of wages and determinants.” Working Paper no.15333 (IZA Institute of Labor Economics, 2022), available at https://docs.iza.org/dp15333.pdf.

58. Nicole Fortin, Thomas Lemieux, and Neil Lloyd, “Right-to-Work laws, unionization, and wage setting.”

59. Mark Stelzner, “The new American way–how changes in labour law are increasing inequality.”

60. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Union members – 2022,” (2023), available at https://www.bls.gov/news.release/union2.nr0.htm.

61. Worker voice in America: Is there a gap between what workers expect and what they experience?” IRL Review, 72 (1) (2019), available at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0019793918806250. See also Justin McCarthy, “U.S. approval of labor unions at highest point since 1965,” Gallup, August 30, 2022, available at https://news.gallup.com/poll/398303/approval-labor-unions-highest-point-1965.aspx.

62. U.S. National Labor Relations Board, “NLRB General Counsel Jennifer Abruzzo issues memo on captive audience and other mandatory meetings,” April 7, 2022, available at https://www.nlrb.gov/news-outreach/news-story/nlrb-general-counsel-jennifer-abruzzo-issues-memo-on-captive-audience-and. See also Lauren Kaori Gurley, “Nearly 80,000 federal employees joined unions in a year, White House says,” The Washington Post, March 17, 2023, available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2023/03/17/unions-federal-workers-harris-biden-white-house-task-force/. See also “Fact sheet: The Bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act creates good-paying jobs and supports workers,” (White House, 2021), available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/08/03/fact-sheet-the-bipartisan-infrastructure-investment-and-jobs-act-creates-good-paying-jobs-and-supports-workers/.

63. Chiara Criscuolo and others, “An industrial policy framework for OECD countries,” (Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2022), available at https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/science-and-technology/an-industrial-policy-framework-for-oecd-countries_0002217c-en.

64. Congressional Research Service, “Industrial policy and international trade,” (2023), available at https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF12119#:~:text=While%20there%20is%20no%20formal,and%20trade%20within%20an%20economy.

65. Brian Deese, “Remarks on executing a modern industrial strategy by NEC Director Brian Deese,” (White House, 2022), available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2022/10/13/remarks-on-executing-a-modern-american-industrial-strategy-by-nec-director-brian-deese/.