Overview

The steady movement of women into the U.S. workforce over the past half-century has dramatically changed the composition of family incomes across the country and up and down the income ladder. All these additional earnings, however, have not meant that family income has increased faster than in earlier eras. A breadth of research demonstrates that overall family economic security in the United States has been declining since the 1970s, especially among low- and middle-income families. As a result, even as more women have joined the labor force and families have lost their time for caregiving, too many families’ continue to face economic insecurity.

This issue brief explores how over the past four decades, women’s increased earnings and increased annual hours of work have been essential as families across the United States seek to find and maintain economic security. Using data from the Current Population Survey, we document how family income has changed between 1979 and 2013 for low-income, middle-class, and professional families, decomposing the differences in male earnings and female earnings from greater pay, female earnings from more hours worked, and other sources of income over this time period.

Download FileWomen have made the difference for family economic security (pdf)

Read the full PDF in your browser

This analysis is an extension and update of the analysis presented in the forthcoming book “Finding Time: The Economics of Work-Life Conflict” authored by one of the co-authors of this issue brief, Equitable Growth’s Executive Director and Chief Economist Heather Boushey. Here are our key findings:

- Between 1979 and 2013, on average, low-income families in the United States saw their incomes fall by 2.0 percent. Middle-income families, however, saw their incomes grow by 12.4 percent, and professional families saw their incomes rise by 48.8 percent.

- Over the same time period, the average woman in the United States saw her annual working hours increase by 26.4 percent. This trend was similar across low-income, middle-class, and professional families.

- Across all three income groups, women significantly helped family incomes both because they earned more per hour and worked more per year. Women’s contributions saved low-income and middle-class families from steep drops in their income.

These findings establish that working women, especially those within low-income and middle-income families, have made the key difference in securing earnings for their families. Without women’s added earnings, families would be much worse off.

Women’s changing role in the U.S. labor force

An increasing number of families across the United States, especially low- and middle-income families, are becoming less economically secure. This trend began more than four decades ago, long before the Great Recession of 2007–2009. In light of this increasing instability and stagnant growth in family incomes, families have had to find ways to cope—including an growing reliance on the earnings of women. The role of women in the United States has transformed from predominantly being a wife or mother to being all of these things and a breadwinner.

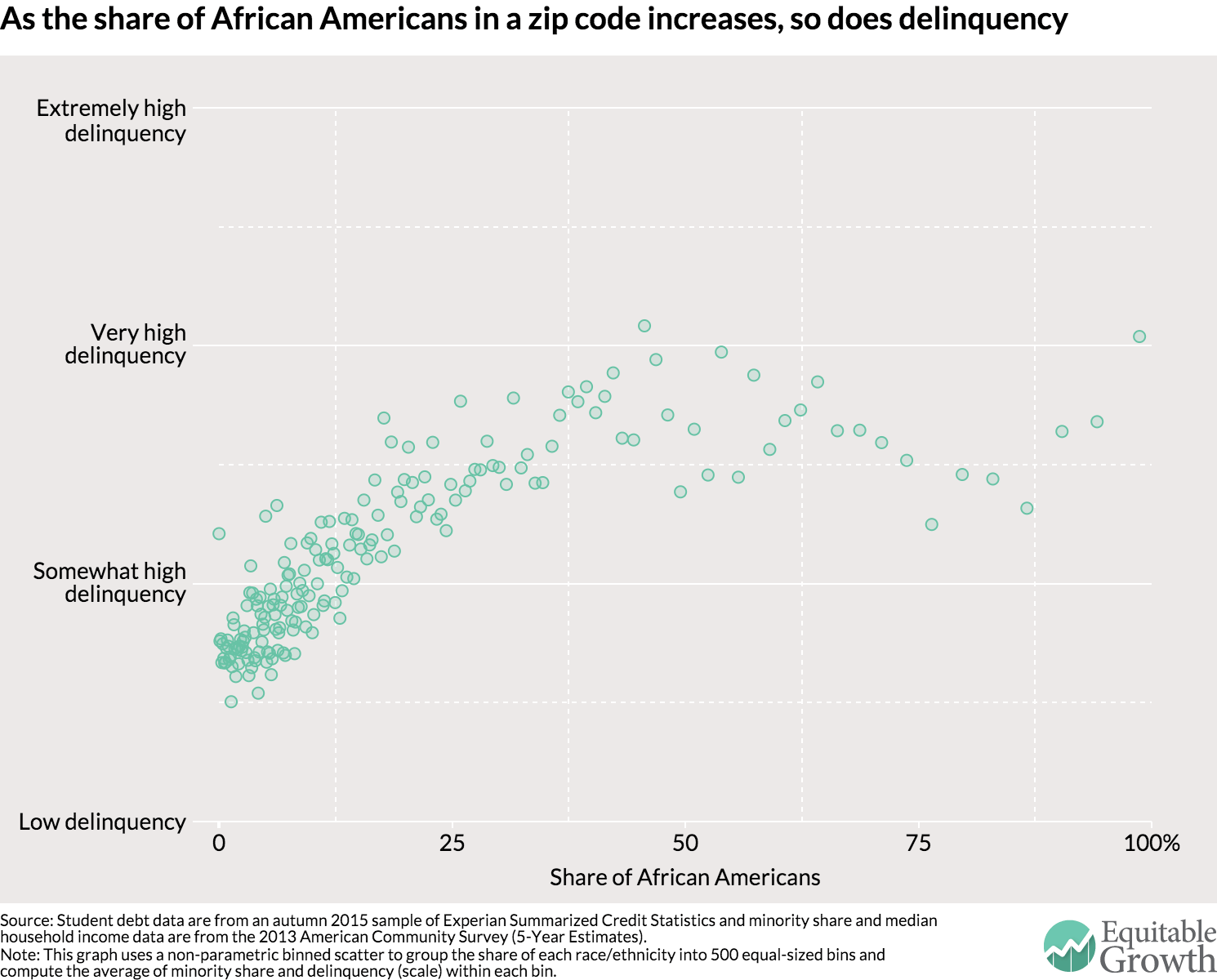

Half a century ago, women—especially middle-class women—began entering the U.S. labor force and staying there, although they were still more likely to be their family’s caregiver for children, the aging, and the ill. And starting in the 1970s, more women started gaining professional degrees, which along with other factors contributed to a sharp rise in women’s labor force participation as well, especially for prime-age working women (ages 25 to 54). By 2000, about 60 percent of all U.S. women were in the labor force, which remained the case until the financial crash in 2007 and the ensuing Great Recession. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

As women engaged more in the labor force, they also started working more hours on average. In 1979, 28.6 percent of all U.S. women were working full time. By 2007, right before the Great Recession, this number had increased to 43.6 percent. This change has made a substantial difference at a macroeconomic level: Our gross domestic product in 2012 would have been $1.7 trillion less if women had not increased their working hours over the past four decades.

Updating and building on the findings that Heather Boushey presents in her forthcoming book, “Finding Time: The Economics of Work-Life Conflict,” this brief explores the difference that women’s increased work hours have made at the family level, and how this effect varies for different types of families. Using data from the Current Population Survey, we calculate how family income changed between 1979 and 2013 for low-income, middle-class, and professional families in the United States, decomposing it by differences in male earnings, female earnings, and other sources of income over that time period. We further dissect the change in female earnings to find what portion of that change is due to increases in pay and what portion is due to working more hours in 2013 in comparison to 1979.

Defining income groupsThis analysis follows the same methodology presented in “Finding Time.” For ease of composition, we use the term “family” throughout the brief, even though the analysis is done at the household level. We split households in our sample into three income groups. Low-income households are those in the bottom third of the income distribution, which means those earning less than $25,440 per year in 2015 dollars. Professional households are those in the top fifth of the income distribution who have at least one household member with a college degree or higher; in 2015 dollars, these households have an income of $71,158 or higher. Everyone else falls in the middle-class category. |

Setting some context

Before we delve into the main analysis, let’s first set some context for how family incomes and women’s hours have changed across low-income, middle-class, and professional families.

How did family incomes change between 1979 and 2013?

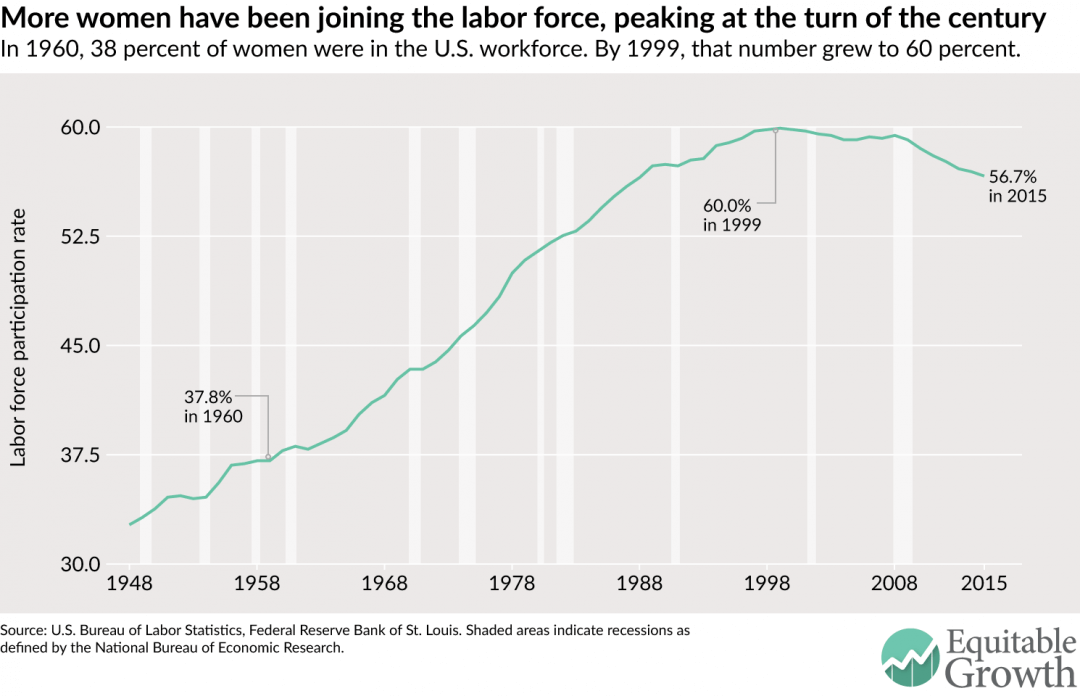

The changes in average U.S. family incomes between 1979 and 2013 show widening inequality, consistent with other research. In 1979, low-income families had an average annual family income of $23,697 in 2015 dollars—by 2013, that number dropped by 2.0 percent to $23,224. Middle-class families only fared marginally better: In 1979, they had an average income of $72,168, which by 2013 rose by 12.4 percent to $81,152. Over the same time period, however, professional families saw a 48.8 percent increase in their average income, going from $132,492 in 1979 to $197,141 in 2013. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

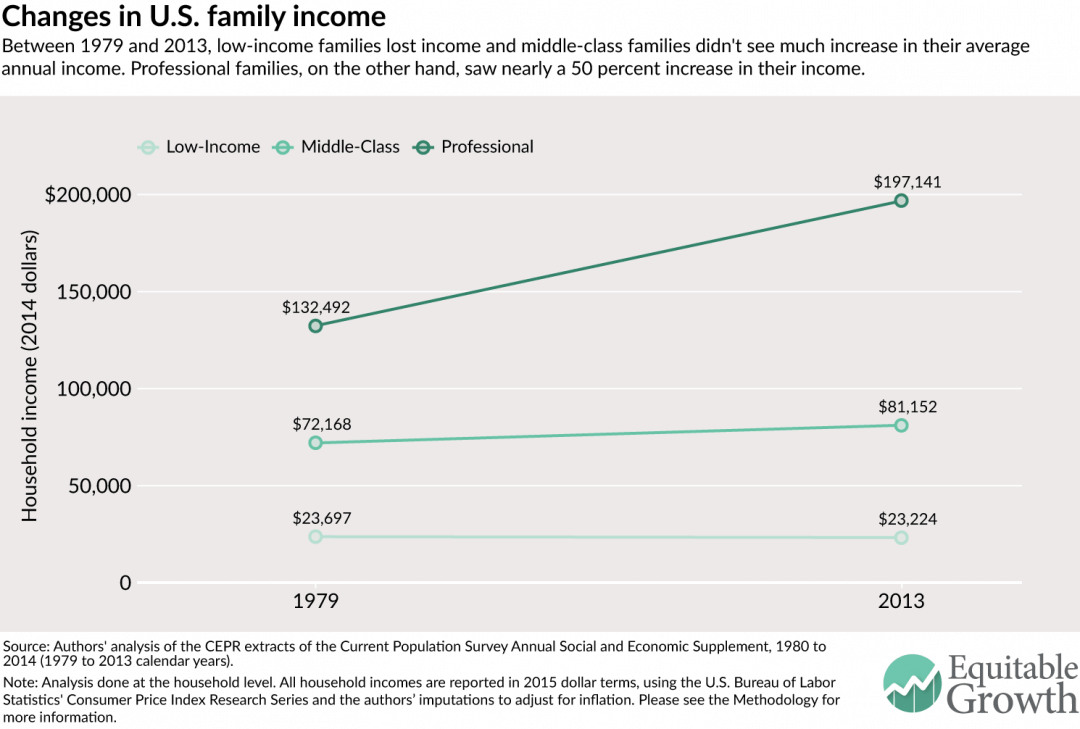

How did women’s working hours change between 1979 and 2013?

Women across all three income groups saw their working hours rise. In 1979, on average, women from low-income families worked 629 hours per year (or 12 hours per week), and by 2013 their annual work hours had grown by 24.1 percent to 780 hours (or 15 hours per week). Similarly, middle-class and professional women’s hours grew by 25.7 percent (from 23 per week in 1979 to 29 hours per week in 2013) and 29.4 percent (from 26 hours per week in 1979 to 34 hours per week in 2013) over that same time period, respectively. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

Decomposing the changes in family income between 1979 and 2013

Figures 2 and 3 establish that between 1979 and 2013, even as women’s working hours increased at parallel rates for all income groups, family income was either stuck or stalled for low-income and middle-class families. This paradox is resolved when we break down the changes in average family income into male earnings, female earnings, and income from Social Security, pensions, or any other non-employment-related source over that same time period.

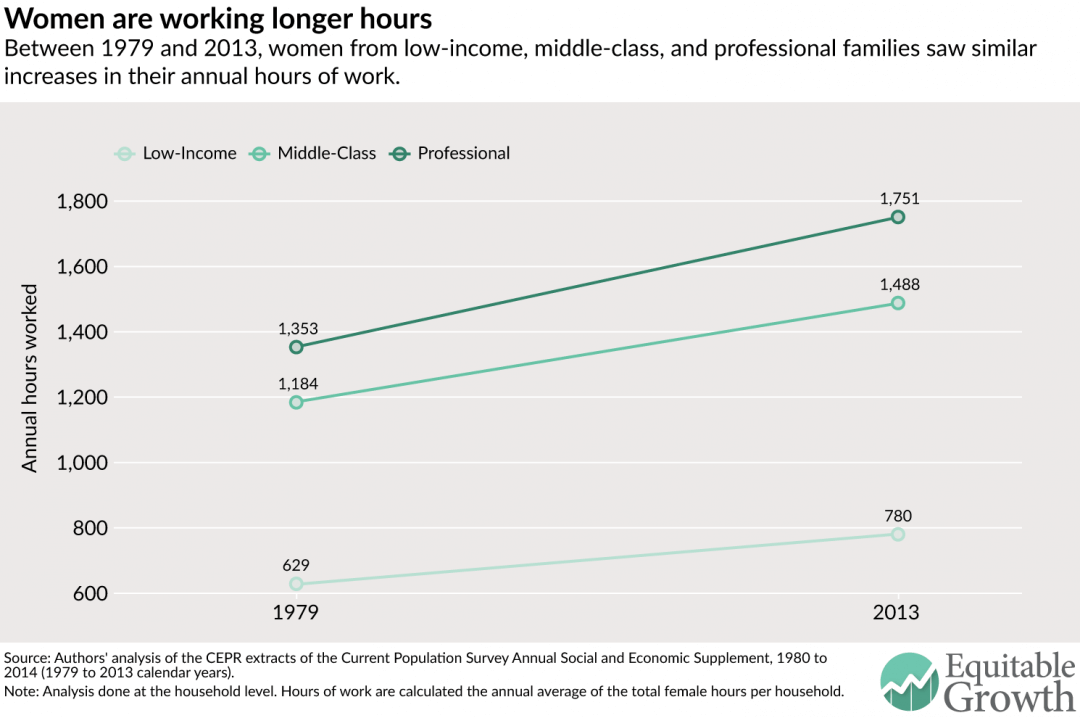

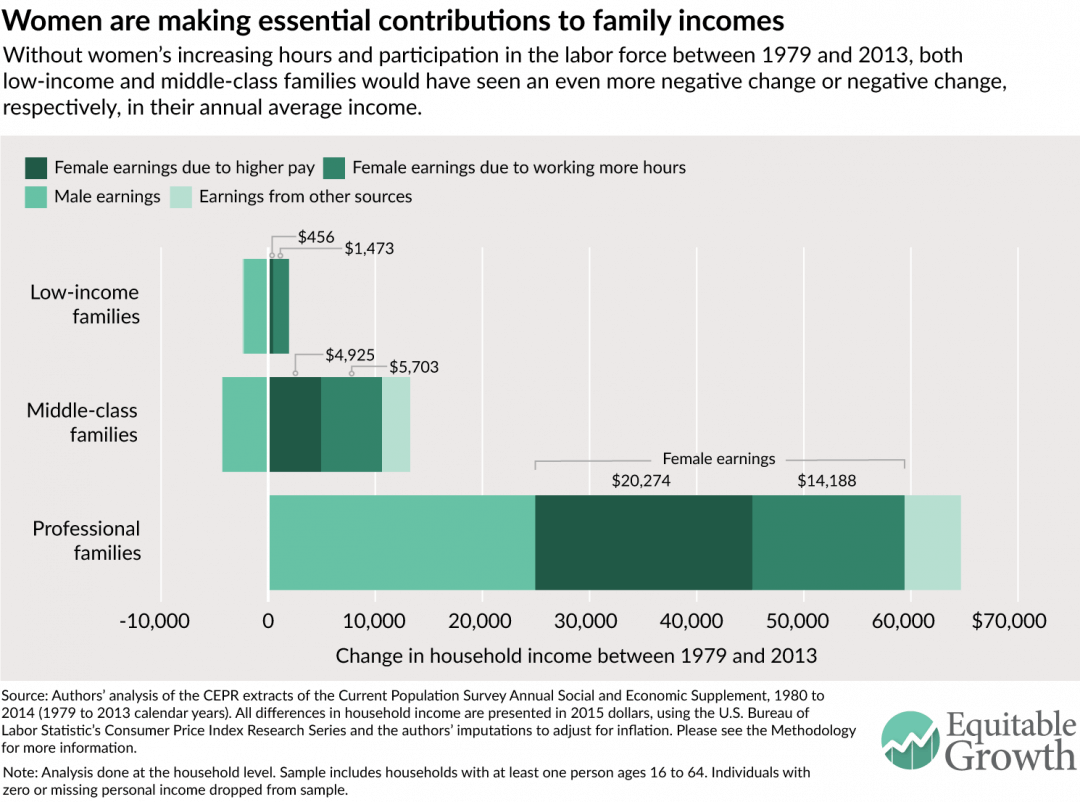

Specifically, we divide female earnings into the portion due to women earning more per hour and that due to women working more per year. To calculate female earnings stemming directly from the additional hours worked, we take the difference between 2013 female earnings and the hypothetical earnings of women if they earned 2013 hourly wages, but worked the same hours as women did in 1979. (For more on how we did this calculation, please see our Methodology.) It turns out that this is an important distinction because, as shown in Figure 4, the difference in female earnings due to additional hours has made a significant positive difference for every income group, especially for low-income and middle-class families. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

Between 1979 and 2013, low-income families saw their income fall, as shown in Figure 2; in Figure 4, we see that this is because men’s earnings fell. Women not only increased their working hours but also their pay per hour—so much so that their overall contribution grew the average annual family income by $1,929 making up for much of the losses from declining male earnings. Women’s earnings from working additional hours alone added $1,473.

In middle-class families, the average annual income grew by $8,984. But, like low-income families, this change was also entirely due to women’s added hours and earnings. Between 1979 and 2013, women’s earnings from working more hours accounted for the largest share of the gains, adding $5,703. The second-largest factor was once again women’s pay, which contributed about $4,925. Also similar to low-income families, men’s earnings pulled down overall income within middle-income families, falling by $4,278.

Professional families experienced significant income growth between 1979 and 2013 across all earnings and income categories. As with low-income and middle-class families, women’s earnings from higher pay and increased hours were the most important factor. Women’s earnings from pay increased by an average of $20,274 per year, while women’s earnings from more hours accounted for $14,188. However, as opposed to families further down the income spectrum, men in professional families earned on average $24,936 more per year over this period, helping boost family income.

Conclusion

Across every income group, women’s increased working hours have helped bolster family economic security. But for low-income and middle-class families, women’s contributions, particularly from working more per year, have been essential in abating the effects of stuck or stalled family income growth. Simply, women’s participation in the workforce has made the key difference for middle-class families and more vulnerable families on the brink.

Families have benefited greatly from the changing roles of women in the home and the work force. Yet across the U.S. job market and across all levels of the income distribution, men and women face daily conflicts between work and family. As researchers strengthen the finding that what happens within a family is just as important to the economy as what happens within a business, it is imperative that we design policies that support families where they live, work, and play. These policies, among them work flexibility, paid family and medical leave, and child care, must be designed so that their distributional effects help all families equitably in order to truly strengthen our economy.

Heather Boushey is the Executive Director and Chief Economist at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth and the author of the forthcoming book from Harvard University Press, “Finding Time: The Economics of Work-Life Conflict.” Kavya Vaghul is a Research Analyst at Equitable Growth.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank John Schmitt, Ben Zipperer, Dave Evans, David Hudson, and Bridget Ansel. All errors are, of course, ours alone.

Methodology

The methodology used for this issue brief is identical to that detailed in the Appendix to Heather Boushey’s “Finding Time: The Economics of Work-Life Conflict.”

In this issue brief, we use the Center for Economic and Policy Research extracts of the Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement for survey years 1980 and 2014 (calendar years 1979 and 2013). The CPS provides data on income, earnings from employment, hours, and educational attainment. All dollar values are reported in 2015 dollars, adjusted for inflation using the Consumer Price Index Research Series available from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Because the Consumer Price Index Research Series only includes indices through 2014, we used the rate of increase between 2014 and 2015 in the Consumer Price Index for all urban consumers from the Bureau of Labor Statistics to scale up the Research Series’ 2014 index value to a reasonable 2015 index estimate. We then used this 2015 index value to adjust all results presented.

For ease of composition, throughout this brief we use the term “family,” even though the analysis is done at the household level. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, in 2014, two-thirds of households were made up of families, defined as at least one person related to the head of household by birth, marriage, or adoption.

We divide our sample into three income groups—low-income, middle-class, and professional households—using the the definitions outlined in “Finding Time.” For calendar year 2013, the last year for which we have data at the time of this analysis, we categorized the income groups as follows:

- Low-income households are those in the bottom third of the inflation- and size-adjusted household income distribution. These households had an income of below $25,440 (as compared to $25,242 and below for 2012). In 1979, 28.3 percent of all households were low-income, increasing to 29.7 percent in 2013. These percentages are slightly lower than one third because the cut-off for low-income households is based on household income data that includes persons of all ages, while our analysis is limited to households with at least one person between the ages of 16 and 64. The working-age population (16 to 64) typically has higher incomes than older workers, and as a result, the working-age population has somewhat fewer households that fall into this low-income category.

- Professionals are those households that are in the top quintile of the inflation- and size-adjusted household income distribution and have at least one member who holds a college degree or higher. In 2013, professional households had an income of $71,158 or higher (as compared to $70,643 or higher in 2012). In 1979, 10.2 percent of households were considered professional, and by 2013, this share had grown to 16.8 percent.

- Everyone else falls in the middle-class category. For this group, the household income ranges from $25,440 to $71,158 in 2013 (as compared to $25,242 to $70,643 in 2012); the upper threshold, however, may be higher for those households without a college graduate but with a member who has an extremely high-paying job. This explains why within the middle-income group, the share of households exceeds 50 percent: The share of middle-income households declined from 62 percent in 1979 to 53.4 percent in 2013.

Note that all cut-offs above are displayed in 2015 dollars, using the inflation adjustment method presented earlier.

In our analysis, we limit the universe to persons with non-missing, positive income of any type. This means that even if a person does not have earnings from some form of employment but does receive income from Social Security, pensions, or any other source recorded by the CPS, they are included in our analysis.

These data are decomposed into income changes between 1979 and 2013 for low-income, middle-class, and professional families. The actual household income decomposition uses a simple shift-share analysis to find the differences in earnings between 1979 and 2013 and calculate the extra earnings due to increased hours worked by women.

To do this, we first calculate the male, female, and other earnings by the three income categories. To calculate the sex-specific earnings per household, we sum the income from wages and income from self-employment for men and women, respectively. The amount for other earnings is derived by subtracting the male and female earnings from total household earnings. We average the household, male, female, and other earnings by each income group for 1979 and 2013, and take the differences between the two years to show the raw changes in earnings by each income group.

To find the change in hours, for each year by household, we sum the total hours worked by men and women. We average these per-household male and female hours, by year, for each of the three income groups.

Finally, we calculate the counterfactual earnings of women. We use the 2013 earnings per hour for women and multiply it by the 1979 hours worked by women. Finally, we subtract this counterfactual earnings from the female earnings in 2013, arriving at the female earnings due to additional hours.

One important point to note is that because of the nature of this shift-share analysis, the averages don’t exactly tally up to the raw data. Therefore, when presenting average income, we use the sum of the decomposed parts of income. While economists typically show median income, for ease of composition and the constraints of the decomposition analysis, we show the averages so that the data are consistent across figures. Another important note is that we make no adjustments for changes over time in topcoding of income, which likely has the effect of exaggerating the increase in professional families’ income relative to the other two income groups.