According to the National Organization for Women, today is African American women’s Equal Pay Day, when African American women will have worked all of 2015 through today—an additional 236 days—in order to earn the same amount that men made last year. In other words, in 2015, on average, black women earned about 63 cents per every dollar earned by a man. This isn’t necessarily surprising given what the research says about pay equity, but it sparked further interest at Equitable Growth to see what the wage gap looks like for African American women up and down the income ladder.

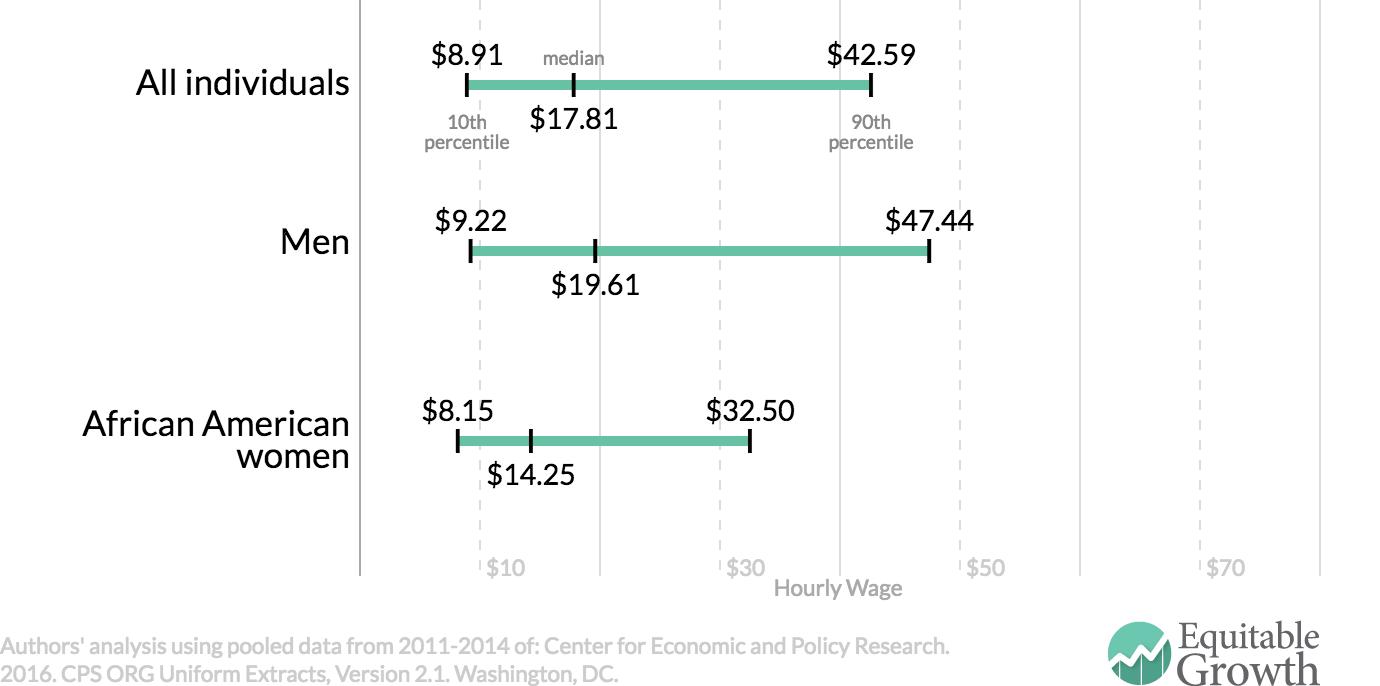

Equitable Growth’s new interactive tool allows for a careful look. Though our interactive’s numbers don’t quite match the National Organization for Women’s Equal Pay Day levels due to methodological differences (primarily, our interactive covers a slightly different time period), they still prove the same point: Men across the board are paid substantially more than African American women. By our calculations, men earn a median wage of $19.61 per hour, while African American women earn a median wage of $14.25, an hourly wage differential of $5.36 or a pay gap of about 38 percent relative to African American women’s hourly rate. (See Figure 1.)

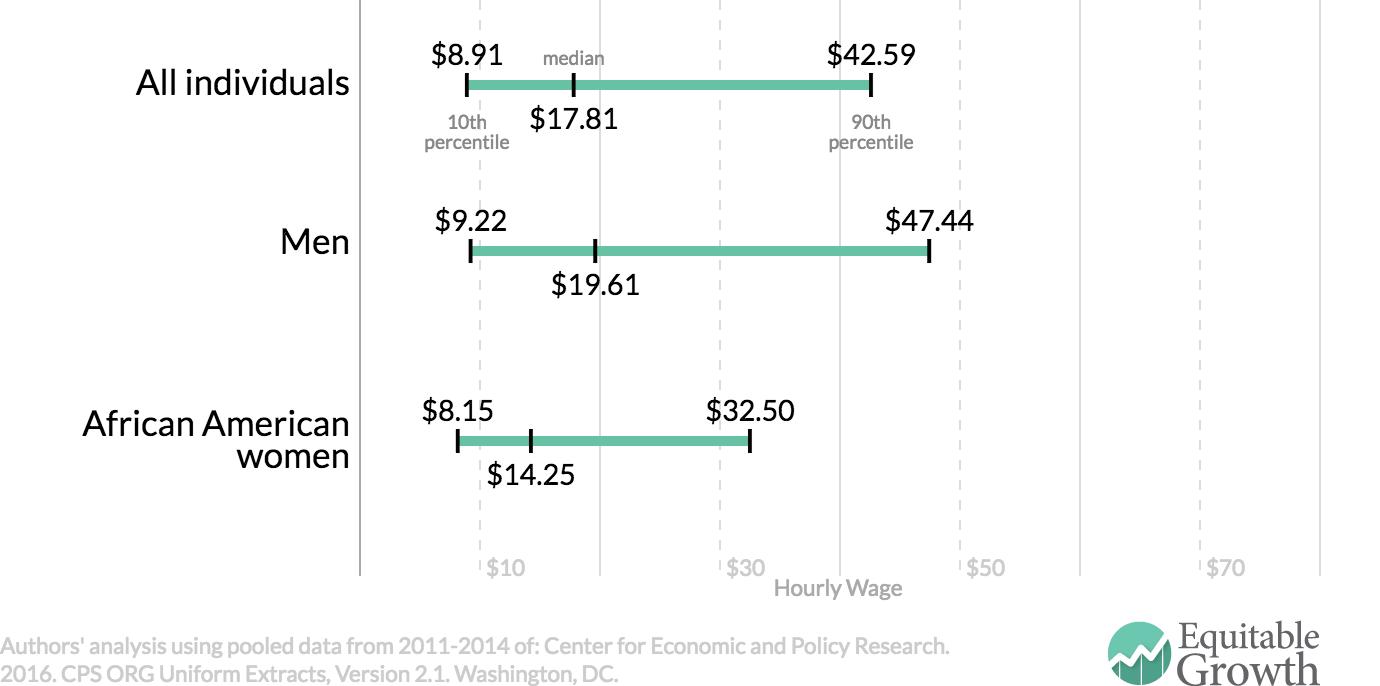

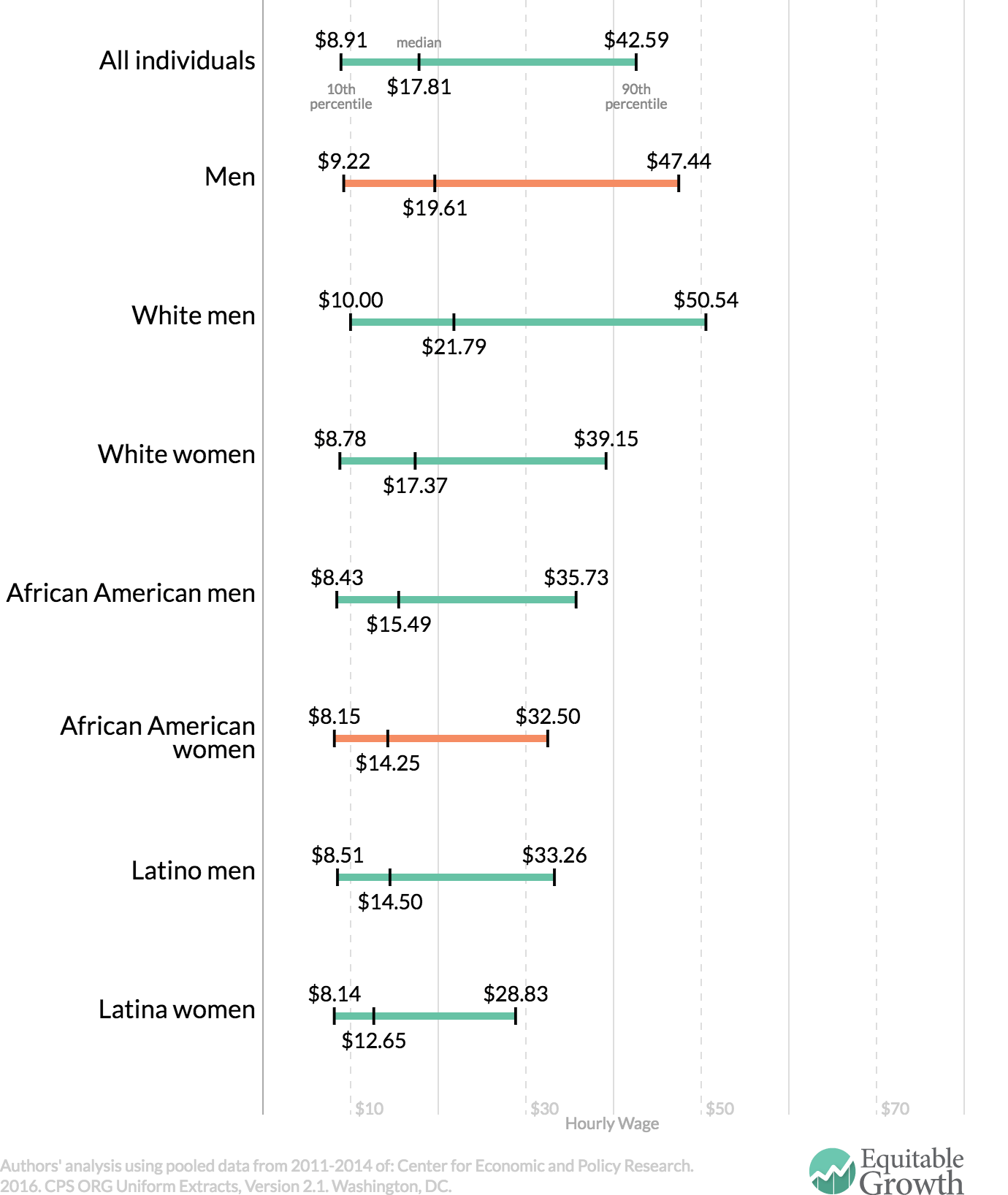

Figure 1

When looking across the wage distribution detailed in Figure 1, the same pattern is clear—men get paid more. Low-wage male workers make about $9.22 per hour compared to the $8.15 earned by low-wage black women, a pay gap of about 13 percent. Near the top, however, the pay gap is substantially larger, approximately 46 percent, with men earning $47.44 and African American women earning $32.50.

These data also demonstrate that the pay gap between men and black women is narrower for workers at the bottom, but widens as a worker moves up the wage distribution. This same pattern also holds when we observe the wage distributions for different genders, races, and ethnicities. (See Figure 2.)

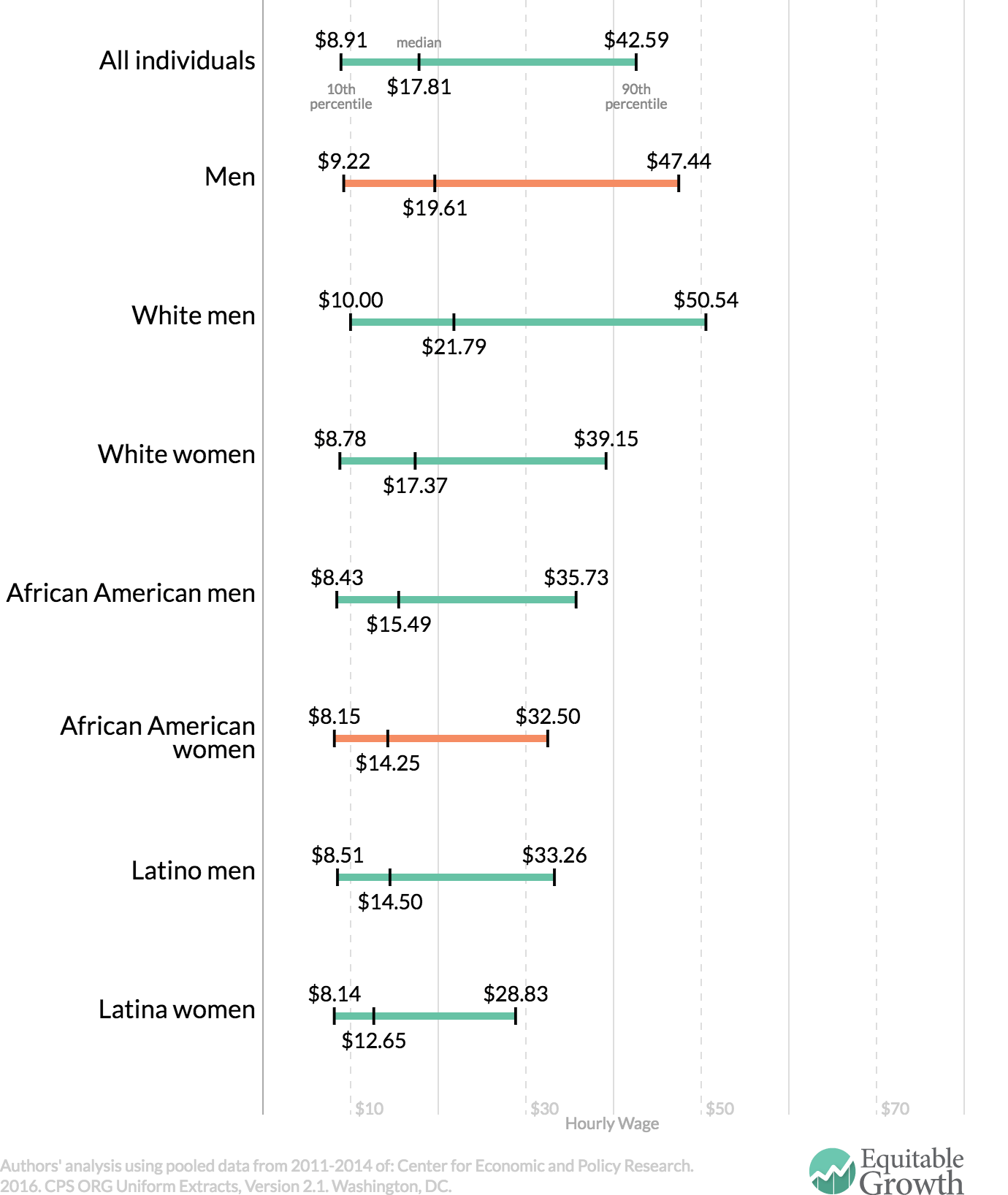

Figure 2

At the bottom of the distribution, low-wage workers from different demographic backgrounds have relatively similar wages. Low-wage Latinas and African American women earn the least ($8.14 and $8.15 per hour, respectively), while low-wage white men earn the most ($10.00). This clustering of wages at the bottom is likely a result of current federal and state minimum wage policies, which legally mandate employees to be paid at least $7.25 per hour (or more, in many states).

For workers in the middle range of each demographic group, the gender gap is bigger. Median-wage Latinas and African American women are the lowest-wage recipients, earning $12.65 and $14.25 per hour, respectively. In contrast, white men earn the highest median wages, making $21.79. At the top, where the gap is largest, the lowest wages are $28.83 (Latinas) and $32.50 (African American women), while the highest wage is $50.54 (white men), a difference of more than $20.00. The spreading out at the top reflects discrimination across both gender and race.

What explains these wage gaps? On one hand, social and cultural norms at work, occupational sex segregation, and a lack of workplace policies, among other factors, play a role in pushing women out of higher-paying jobs. On the other hand, racial discrimination, which appears in hiring practices and other labor market interactions, disproportionately leaves workers of color with lower pay than their white counterparts. African American women (and Latinas) are doubly disadvantaged, as they experience both of these forms of discrimination.

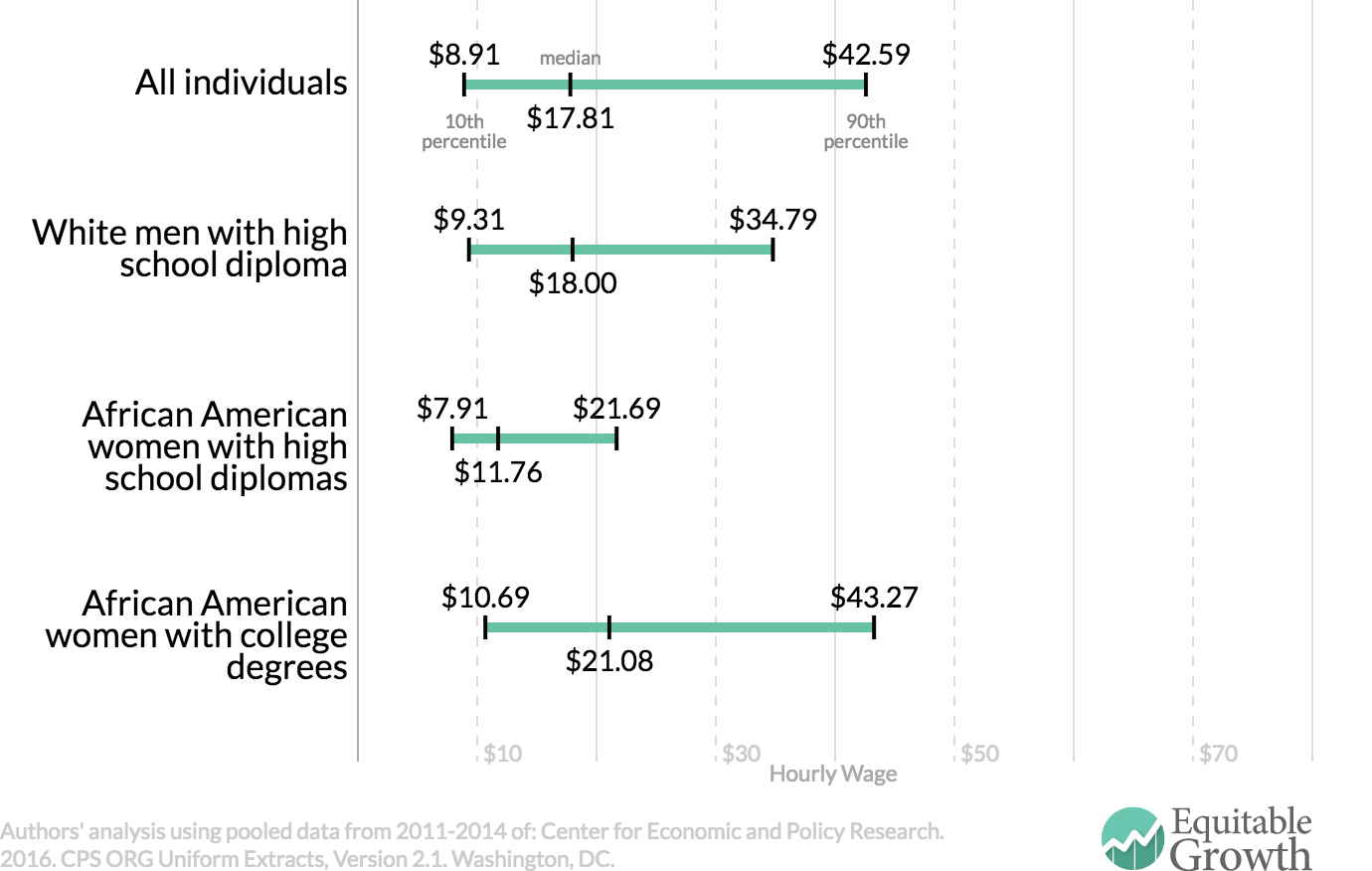

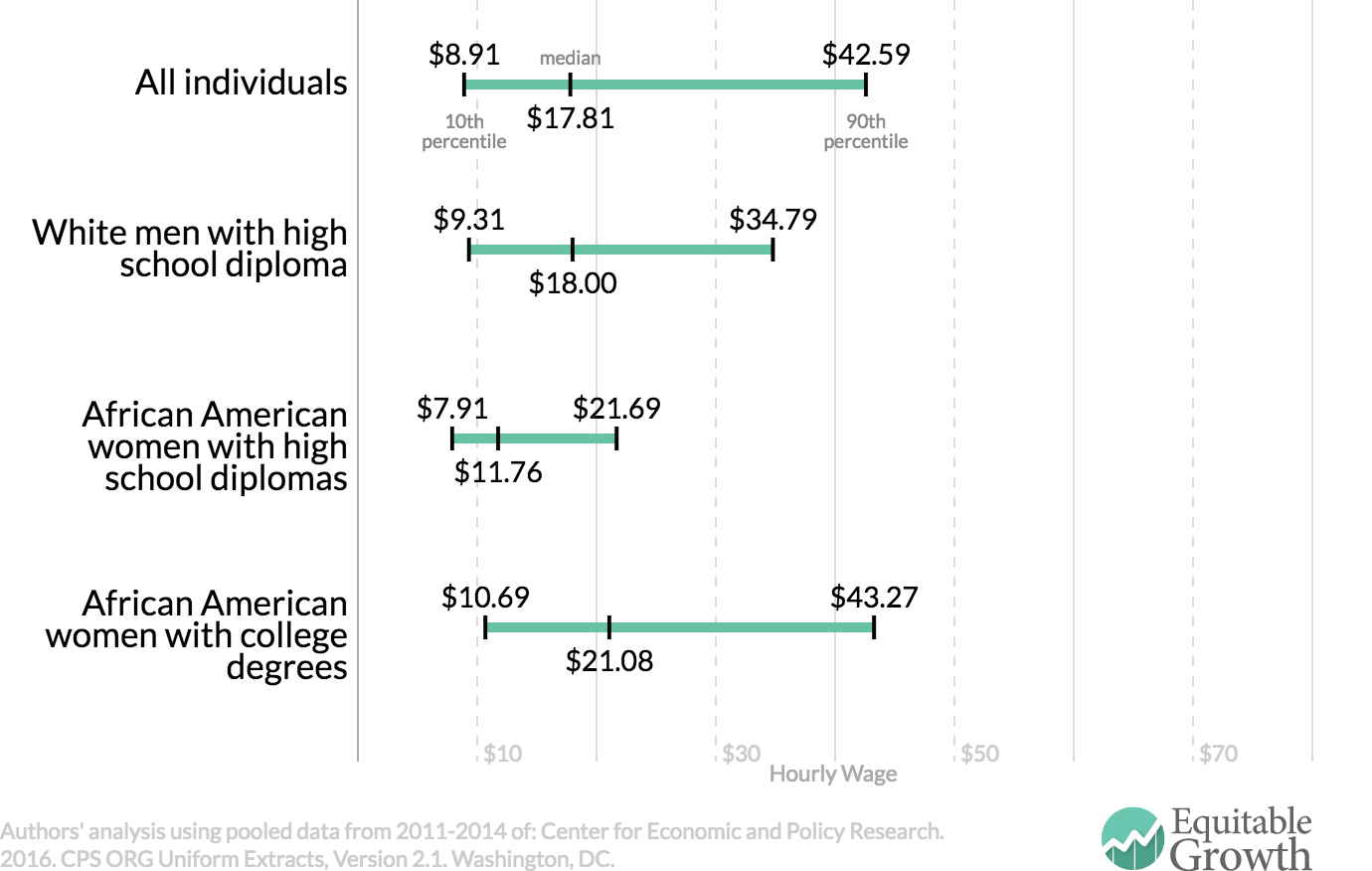

Increasing educational attainment by women of color is probably the most commonly suggested solution to closing the gender wage gap. Yet over the past two decades, women have outpaced men in college enrollment and college enrollment for black women has surged. Despite these gains in education, African American women still earn less. So other solutions would seem to be in order. But first, it’s worthwhile to examine the wage distribution by a worker’s educational attainment. Comparing the earnings of white men with high school degrees to African American women with college degrees shows there are many similarities in their wages despite the much higher level of educational attainment for this group of African American women. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

The lowest-paid white men with high school diplomas earn $9.31 per hour, which is only about 15 percent less than the $10.69 earned by African American women with a four-year college degree. At the median, white men with a high school degree make $18.00 per hour, or only about 17 percent less than the $21.08 earned by the median college-educated African American women. Even for the best paid workers in both groups, the pay gap is only about 22 percent, with white male high school graduates receiving $34.79 per hour, compared to $43.27 top-earning African American women with college degrees.

Closing the pay gap for African American women clearly is no simple task. On the policy front, raising the minimum wage and the tipped minimum wage at the federal, state, and local levels would make a positive difference for women of color. So, too, would increased unionization, crackdowns on workplace discrimination, and improved work flexibility and childcare policies. But the wage gap will persist for African American women as long as structural racism goes unaddressed, which admittedly is a more complex and challenging issue. In the meantime, African American women’s Equal Pay Day helps serve as a reminder that much work is left in order to achieve pay equity across gender and race.