- : Monetary Policy and Inequality in the United States: We study the effects of monetary policy shocks on—and their historical contribution to—consumption and income inequality in the United States since 1980…

- Mark Thoma: Why We Need a Fiscal Policy Commission: During the Great Recession, monetary policymakers were aggressive and creative….

- Ruixue Jia (2014): The Legacies of Forced Freedom: China’s Treaty Ports

- Gabriel Chodorow-Reich and Johannes Wieland: Secular Labor Reallocation and Business Cycles: We study how economies respond to idiosyncratic shocks which induce reallocation of labor across industries….

- Ruddier Bachmann and Eric Sims: Confidence and the Transmission of Government Spending Shocks: In a standard structural VAR, an empirical measure of confidence does not significantly react to spending shocks and output multipliers are around one…

- Marc Andreessen: Software Programs the World: We frequently have delegations from all over the US and the world who come in and ask: “What can we do to have our own Silicon Valley?”…

- Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas et al.: The Greek Crisis: An Autopsy: The Greek crisis is one of the worst in history, even in the context of recorded ‘trifecta’ crises – the combination of a sudden stop with output collapse, a sovereign debt crisis, and a lending boom/bust…

Should Reads:

- Laurence Ball: The Fed and Lehman Brothers

- Chris Dixon: Eleven Reasons To Be Excited About The Future of Technology

- Joe Stiglitz: Prizes, Not Patents

- Nick Rowe: Alpha Banks, Beta Banks, and Negative Rates

- Mark Carney: Inflation Report Q&A

- J. Bradford DeLong (2008): The Republic of the Central Banker

- Weekend Reading; Joe Seligman (1983): Can You Beat the Stock Market?

- For the Weekend…: Guinness: noitulovE (2005):

- Live from Across the Wide Missouri: Is the sprouted quinoa-kamut bread from Ibis Bakery the best loaf of bread in the United States, or just in greater Kansas City?

- What I See as a Marketing Ploy by the University of Chicago…

- Bonnie Kavoussi: Two Classical Models of Leadership: Achilles/Alexander and Aeneas/Augustus

- Brian Resnick: Astronomers just found a new planet that could potentially support life–and it’s really, really close: Astronomers have discovered a new, potentially habitable planet circling Proxima Centauri, the closest star to our own. This is likely the nearest planet outside our solar system that we’ll ever find. What’s more, it should, in theory, be warm enough for liquid water–and warm enough for life…

- Alex Beggs: 5 Chefs on How They’d Doctor Up Frozen Pizza

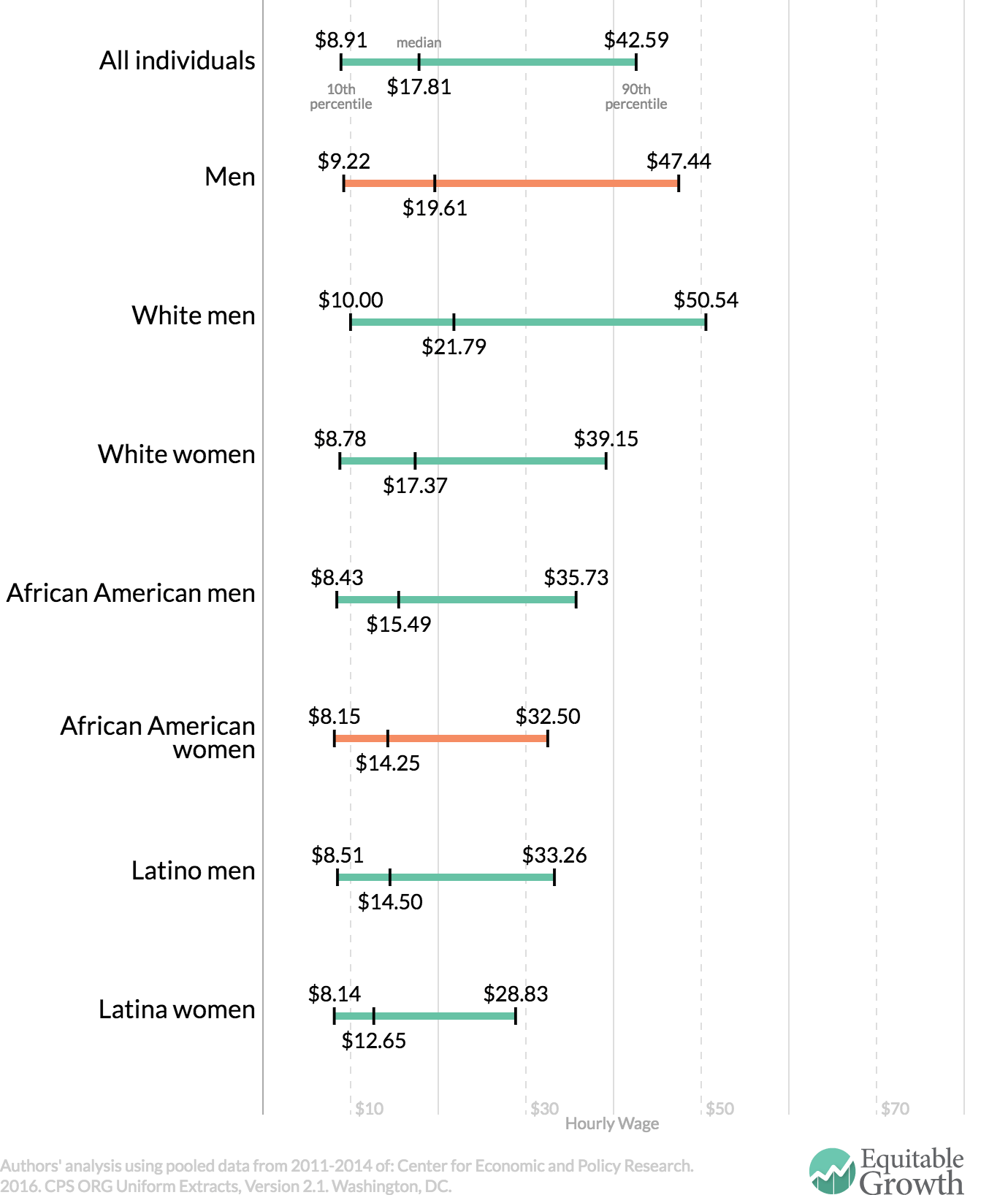

- : Why we need better re-employment policies for formerly incarcerated African American men