New study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences shows schedule stability supports U.S. workers and the broader economy

As COVID-19 vaccination rates rise in the United States many businesses, especially in hard-hit industries such as retail and food service, are seeking to fill positions to keep pace with public demand. Securing or returning to a job is a huge relief to workers who faced or narrowly avoided unemployment over the past 18 months, but it also is important to ask what kinds of jobs these service-sector workers are returning to.

Long before the coronavirus pandemic hit, U.S. policymakers were discussing the quality of work schedules for service-sector workers. As discussions about reemployment heat up, many advocates and policymakers are revisiting conversations about job quality. That’s why the time is right to reexamine policy interventions that are designed to ensure scheduling practices in the service sector work well for employers, employees, and the broader U.S. economy alike.

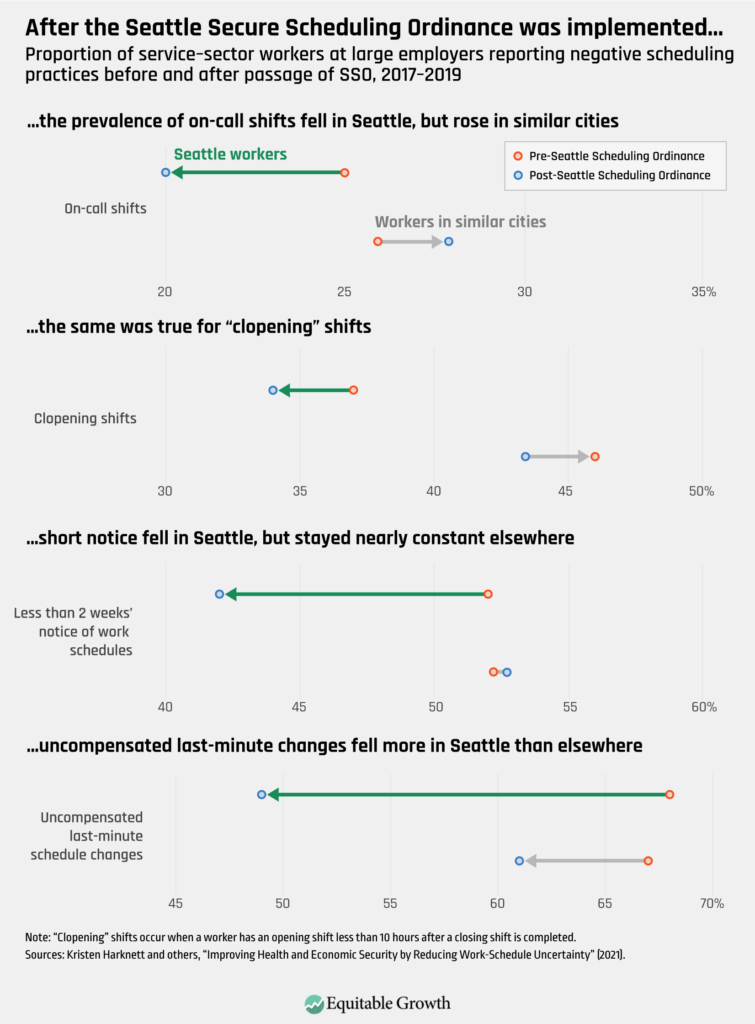

Evidence published last week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on the effects of a stable scheduling law enacted in Seattle provides a useful jumping-off point. Using an innovative approach to data collection, rigorous statistical methods, and building upon previous research conducted in Seattle, the article provides important insights into the effects of stable schedules on workers. Prior to implementation of the ordinance in 2017, the majority of hourly workers in Seattle experienced instability or unpredictability—defined by the researchers as receiving less than 2 weeks’ notice of upcoming work schedules, not receiving compensation for last-minute changes to their schedules, and working an on-call shift or a so-called clopening shift, in which workers have less than 10 hours to rest between shifts or back-to-back closing and opening shifts.

The study’s co-authors—Kristen Harknett of the University of California, San Francisco, Daniel Schneider of Harvard University, and Véronique Irwin of UC Berkeley—collected 1,942 surveys from hourly workers at large retail businesses in Seattle, along with 15,747 surveys from workers in similar cities without scheduling laws as a comparison group. They find that the ordinance decreased the prevalence of workers reporting on-call shifts and clopening shifts by 7 percentage points and 6 percentage points, respectively, increased the share of workers who know their schedule at least 2 weeks in advance by 11 percentage points, and decreased the share of workers experiencing last-minute shift changes without pay by 13 percentage points. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

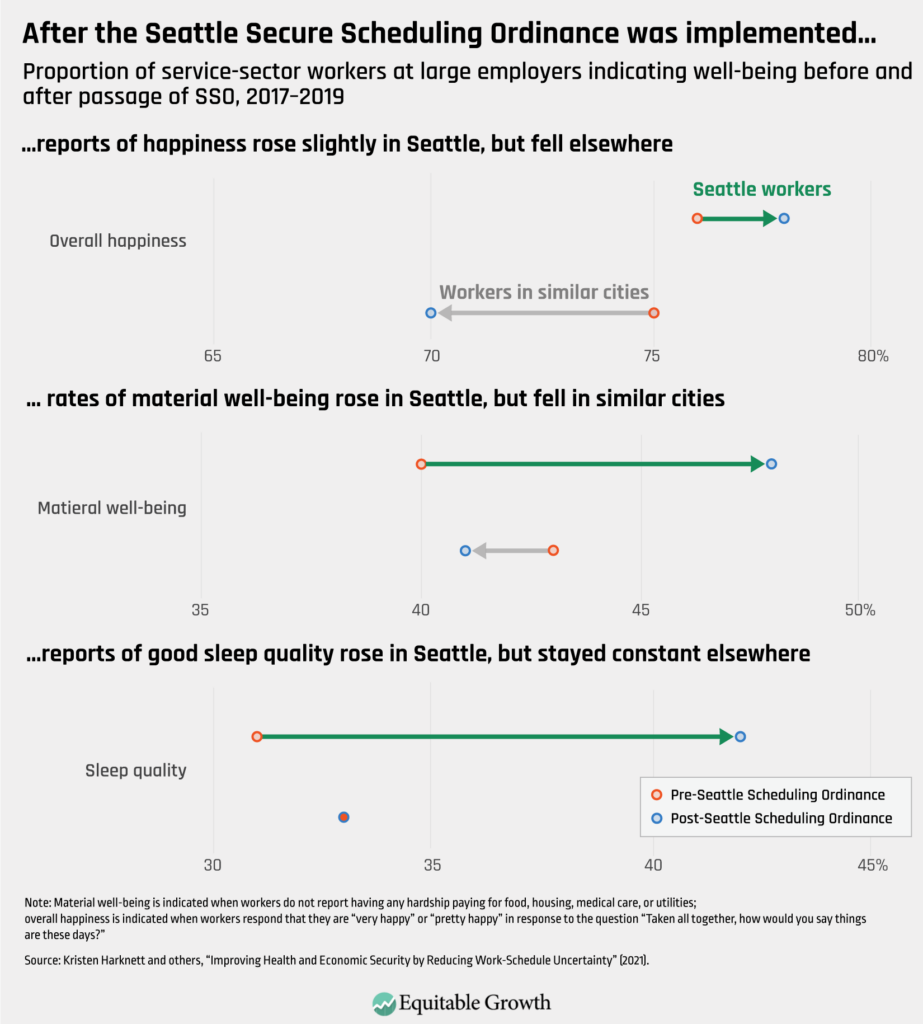

But that’s not all. The ordinance also had an impact on these employees outside of the workplace. Workers reported an improvement in their material well-being: The ordinance was associated with a 10 percentage point fall in rates of material hardship. It also was associated with an 11 percentage point increase in reports of good sleep quality and a 7 percentage point increase in levels of overall happiness. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

In sum, the ordinance not only improved working conditions in terms of schedule stability but also enhanced Seattle workers’ lives and well-being outside of work and bettered their financial stability.

The study’s co-authors make a point of noting that their findings do not indicate that hourly workers in Seattle no longer have unstable schedules. In fact, they note that many workers still report a fair amount of unpredictability and instability. For instance, 40 percent of workers covered by the ordinance reported less than 2 weeks’ notice of their schedules 2 years after the law took effect. This suggests that the ordinance’s accompanying training and awareness campaign may have fallen short of its goal to educate the city’s workforce about these changes. The continued high rates of unpredictable schedules also serve as an important reminder that labor standards enforcement is a key—and perhaps missing or flawed—piece of carrying out these schedule stability ordinances.

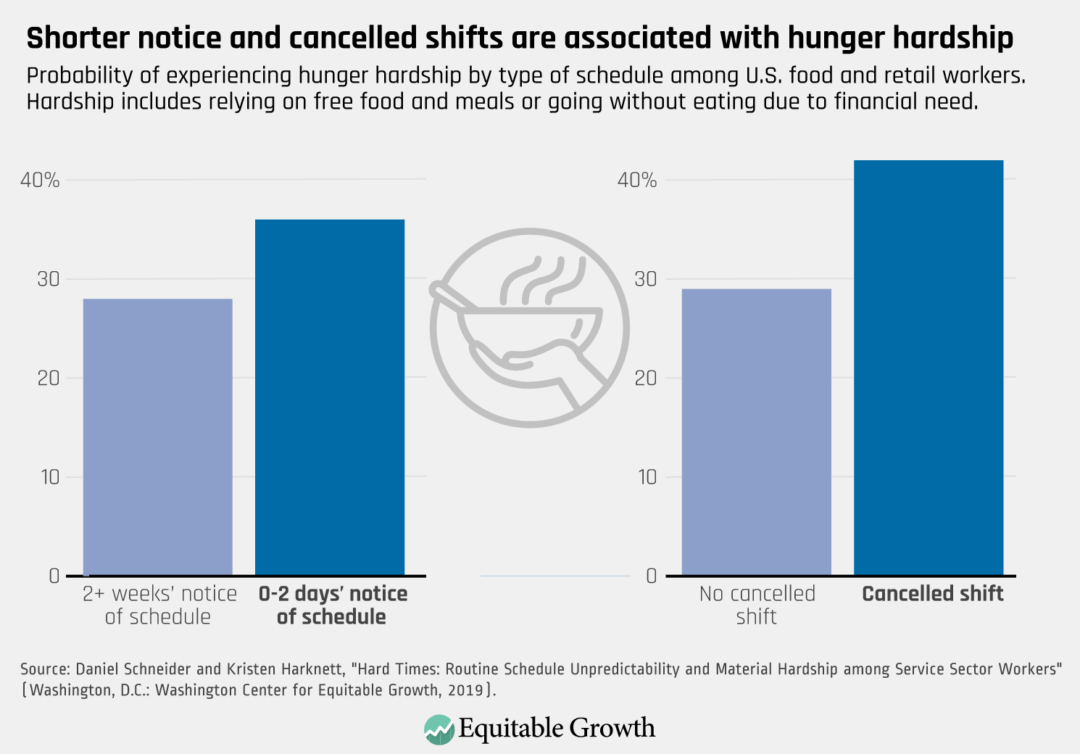

The study is a fascinating addition to the literature on work schedules, which has generally been focused on two main areas. One strand of the existing research examines the associations between scheduling practices and outcomes such as happiness, levels of distress, sleep quality, and financial security. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

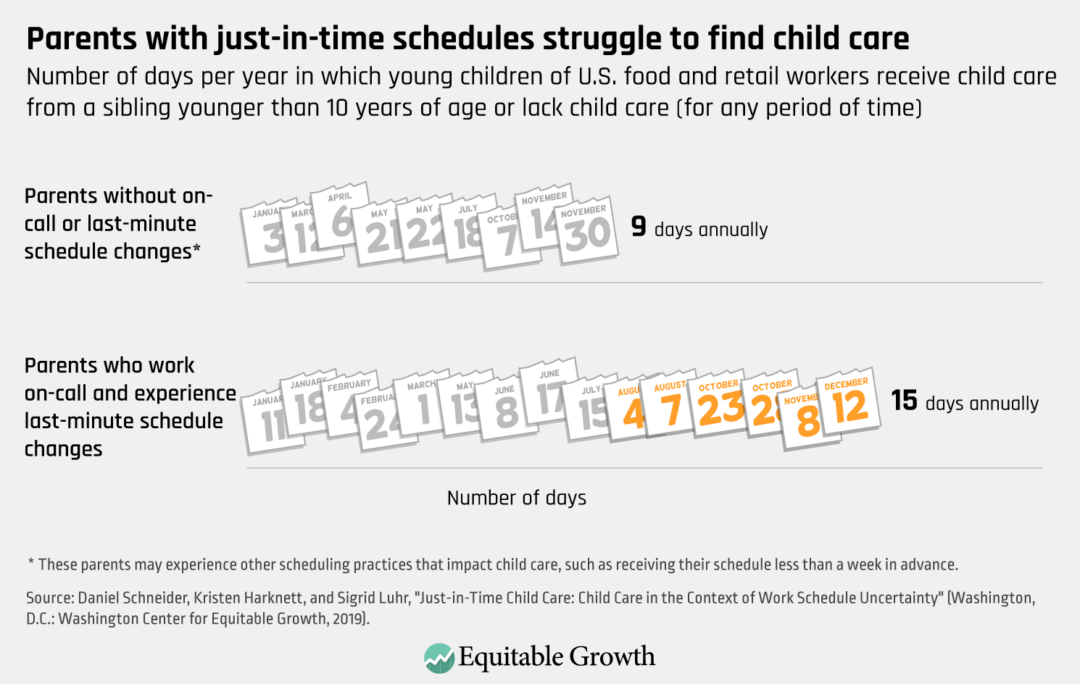

This area of research also looks into the effects of schedule stability on child care arrangements, finding that better schedules are associated with better outcomes in these domains. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

This body of research also finds that unpredictable and unstable schedules are not distributed equally across the population. Food, retail, and other low-wage service-sector employees—who are disproportionately likely to be workers of color and women workers—frequently face precarious scheduling practices because they are widespread in these industries. These low-wage workers also have been hit the hardest by the coronavirus recession and the continuing COVID-19 pandemic.

Another strand of schedule stability research evaluates interventions at the company level, finding that when companies, such as Gap Inc., implement changes designed to improve schedule quality, workers report improvements such as higher productivity and better sleep quality, and firms report improvements such as decreased turnover, longer job tenure, and increased profits. Reductions in turnover save companies money—replacing an employee can cost an employer an average of 40 percent of that employee’s salary. These outcomes are good for the broader U.S. economy.

Inspired in part by these twin strands of research, nine cities and states have passed “fair workweek laws” that attempt to improve the quality of work schedules in the service sector. Yet, to date, little research has drawn causal conclusions about the impact of these laws. That’s what makes the newly published study so exciting.

It’s important to bear in mind that the three researchers’ surveys with workers took place prior to the onset of the coronavirus pandemic in the United States. This is especially important considering the outsize impact of this public health crisis and the ensuing recession on low-wage and service-sector employees. A separate research team led by Susan Lambert at the University of Chicago’s School of Social Service Administration and Anna Haley at Rutgers University’s School of Social Work plan to release a study later this year that focuses on employer implementation of the Seattle law. The forthcoming study will incorporate the coronavirus pandemic’s impact on staffing and scheduling choices during these times of unprecedented stress and business uncertainty.

Even as the availability of COVID-19 vaccines allows many service-sector workers to feel safer going to work, it’s clear that the precarious working conditions that so many of them face are not conducive to quality living standards and, indeed, exacerbate inequality in the United States. Many service-sector workers are, in fact, not returning to their jobs even as the economy and society reopen, with some preferring to look for jobs with better working conditions and benefits or higher pay.

This body of research suggests that policymakers should heed the evidence on the myriad benefits of predictable schedules and enact scheduling stability laws. This new study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences adds to the existing research that shows how improvements to workers’ schedules reduce turnover, boost worker productivity, and grow company profits, and demonstrates the clear personal and professional benefits for individual workers. Together, this body of work implies that benefits of stable schedules for workers and their families ripple out to the broader U.S. economy, facilitating the current economic recovery and improving life for all U.S. workers and their families.