Jobs report: Amid continued job gains, Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander workers experience the U.S. labor market in different and often hidden ways

Between mid-March and mid-April, the U.S. economy added a strong 428,000 jobs, making it the 12th consecutive month in which employment growth surpasses 400,000 jobs. In addition, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Employment Situation Summary released this morning, the national unemployment rate remained unchanged at 3.6 percent—near the pre-pandemic rate of 3.5 percent. The share of 25- to 54-year-olds with a job dropped slightly to 79.9 percent in April from 80 percent in March, and the labor force participation rate fell, going to 62.2 percent from 62.4 percent in the same period.

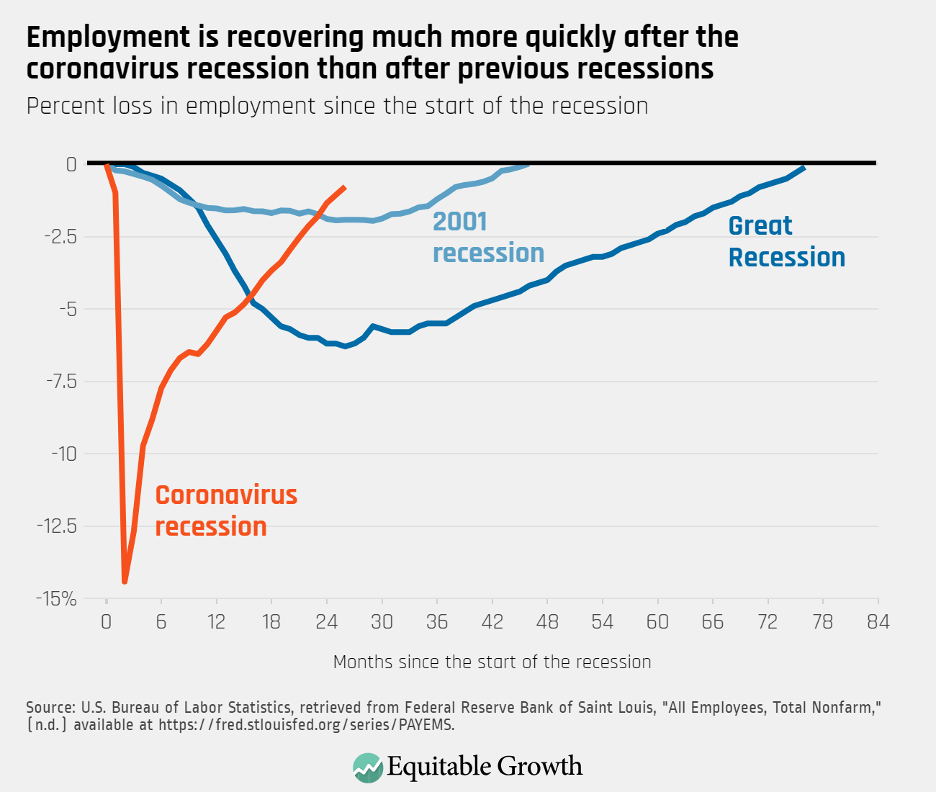

This April also marks 2 years since the U.S. labor market shed a record 20 million jobs in a single month as the COVID-19 pandemic sent shockwaves through the economy. Since then, the recovery in employment has been exceptionally fast, compared to previous recessions. As of last month, there is now only a 1.2 million job deficit with respect to February 2020. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

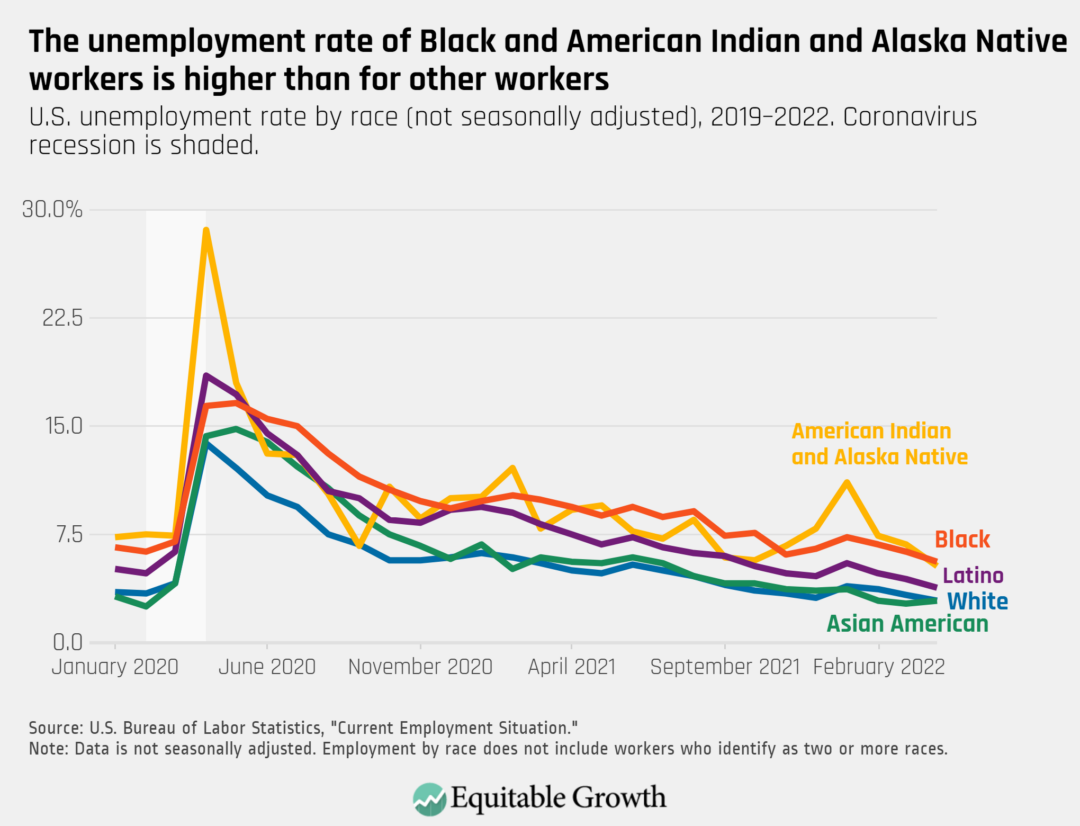

But the recovery has been far from even. Across different demographic groups, joblessness is highest for Black workers, whose unemployment rate went to 5.6 percent in April from 6.3 percent in March. American Indian and Alaska Native workers are facing a 5.3 percent unemployment rate, Latino workers are at 3.8 percent, and White workers and Asian American workers at 2.9 percent. (The Bureau of Labor Statistics began publishing monthly data on American Indian and Alaska Native workers in February 2022, which means this statistic is not available on a seasonally adjusted basis.) (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

While Asian American workers, along with White workers, are currently experiencing the lowest unemployment rate of any other major racial and ethnic group, their unemployment rate saw one of the biggest proportional increases at the onset of the pandemic and was slower to recover than the unemployment rate for White workers. In addition, both aggregate statistics and the topline unemployment rate fail to reflect a full picture of how this group of workers experiences the U.S. labor market.

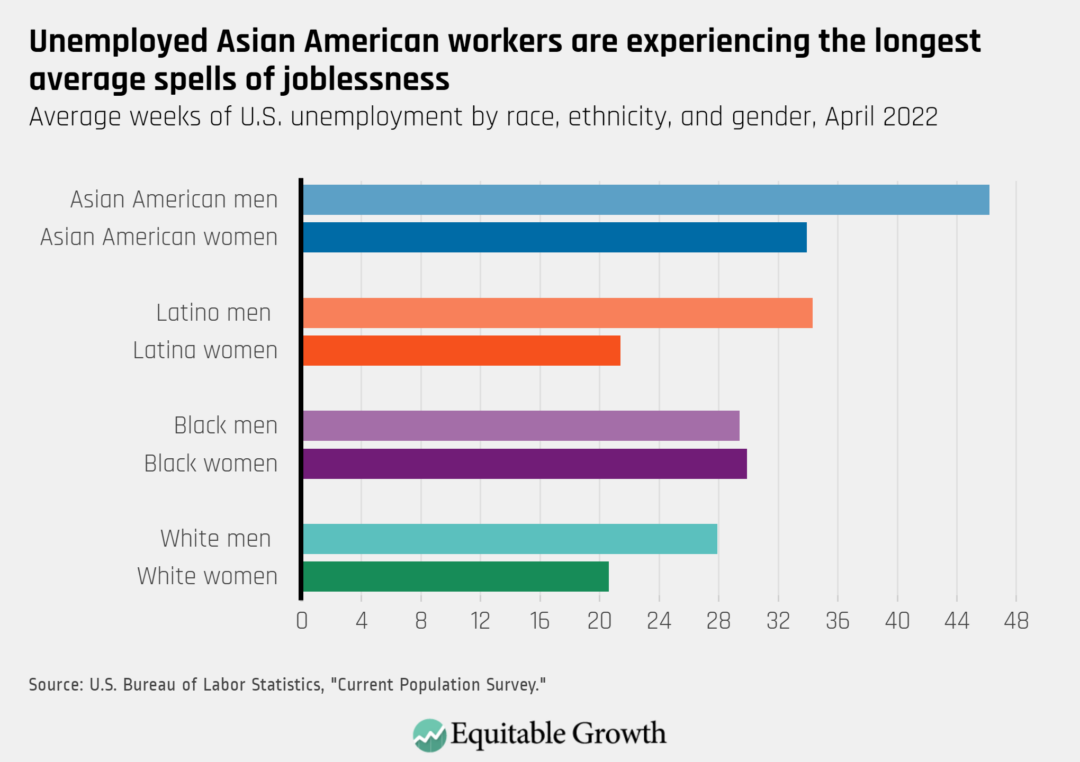

Take long-term joblessness. According to BLS data, since the onset of the pandemic, Asian American workers in general, and Asian American men in particular, faced longer periods of unemployment than their Black, Latino, and White counterparts. In 2021, for instance, it took unemployed Asian American workers an average of 31.7 weeks to find a job—a full 3 weeks longer than the average unemployment spell for all U.S. workers. As of April 2022, the average unemployment duration was 46.2 weeks for Asian American men and 33.9 weeks for Asian American women. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

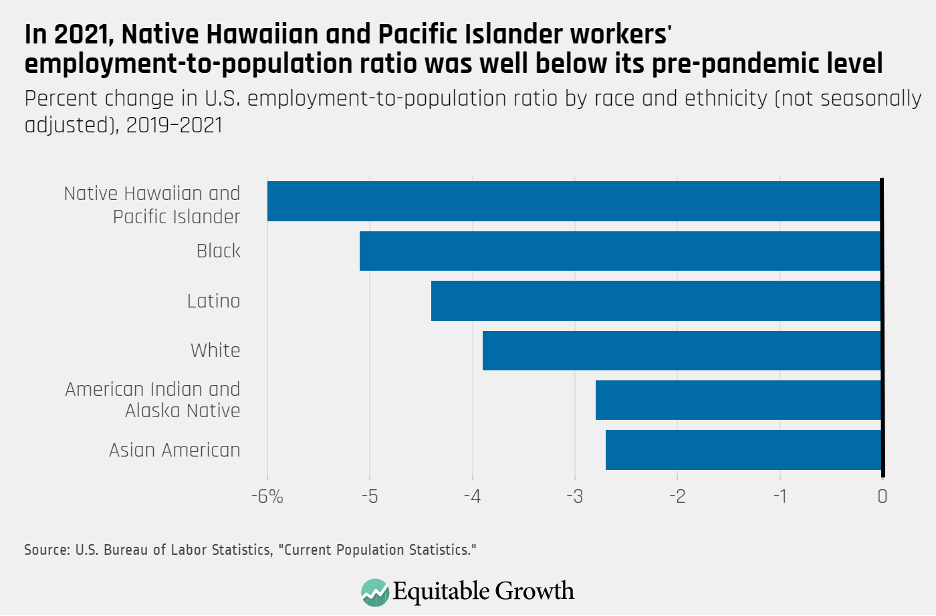

While the Bureau of Labor Statistics does not report monthly statistics on Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander workers, annual data reflect that this group of workers faced big job losses as the COVID-19 pandemic hit. Available data show, for instance, that in 2021, the employment-to-population ratio of NHPI workers had yet to recover the most ground to return to its 2019 level. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

The barriers Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander workers face in the U.S. labor market are often obscured by aggregate statistics

Asian American workers also experienced especially long periods of unemployment during the previous economic downturn. For instance, an analysis by Marlene Kim at the University of Massachusetts Boston shows that in 2010—when long-term joblessness was even more prevalent than during the Great Recession of 2007–2009—almost 49 percent of unemployed Asian American workers had been jobless for 6 months or more, a substantially higher proportion than for Latino workers and White workers and a slightly higher proportion than for Black workers.

Further, Kim found that Asian American workers’ concentration in states where long-term unemployment was especially prevalent and their higher likelihood of having been born outside the United States, alongside racial bias, were all likely explanations for why this group of workers was facing an especially difficult time finding a job after unemployment.

Indeed, a number of studies show that place of birth (about 3 in 4 Asian American, Pacific Islander, and Native Hawaiian workers are foreign born), as well as employment discrimination, hurt AANHPI workers’ employment outcomes, earnings, and opportunities for career advancement. For instance, research has found that getting an education abroad and English language ability can hurt AANHPI workers’ earnings. Further, analyses have found that workers within the AANHPI community can experience discriminatory pay penalties, where lower wages cannot be explained by workers’ level of formal education, years of work experience, and other characteristics believed to determine pay.

As the U.S. economy continues to add jobs, it will be essential to identify and address the obstacles facing AANHPI workers and communities

The jobs recovery continued in April, and the U.S. economy is now 1.2 million jobs away from its pre-pandemic level. Collecting and reporting detailed disaggregated data on AANHPI workers and communities will be crucial to ensure all workers share in the economic recovery, accurately capture experiences of these communities, and inform equitable policymaking. An analysis by Christian Edlagan and Raksha Kopparam at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth shows, for instance, that while AANHPI workers are overrepresented among front-line essential workers, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander workers, Thai workers, and Filipino workers were especially likely to work in occupations that put them at risk of contracting the coronavirus. More broadly, the big disparities in income, occupation, health, and educational attainment make it essential to understand how to target funds and policymaking efforts.

At the same time, policymakers need to invest in robust antidiscrimination enforcement and bolster existing laws to cover workers who are currently unprotected due to gaps in coverage, including independent contractors and others in nontraditional work arrangements. And a robust income support infrastructure is another important component to both reduce inequality and support AANHPI workers who may experience discrimination by improving their outside options.

Policies that support worker power—including raising the minimum wage, adopting a just cause employment standard, and supporting workers’ ability to form a union—are a vital foundation for addressing discrimination and improving earnings and working conditions for AANHPI workers, especially those in low-wage occupations. These changes, paired with innovative approaches to enforcing labor standards, including strategic enforcement and co-enforcement, are especially important to protecting vulnerable workers during times of economic upheaval.