How combating voter suppression can help close the economic divides between Black and White Americans and spur U.S. economic growth

Economic analysis that does not account for political power—who has it and how it is wielded—will inevitably fail to fully capture what keeps the United States from achieving equitable economic growth. The dominant fault line in that battle for political power across the country historically and today is race. And at the center of that fault line are Black Americans, the vast majority of whom are the descendants of those who emerged from enslavement in the 19th century only to face vicious and direct voter suppression until the late 1960s—followed by indirect but still effective tactics to suppress their votes up through the 2020 elections.

Our new report, titled “The consequences of political inequality and voter suppression for U.S. economic inequality and growth,” demonstrates the clear links between access to the ballot box for Black Americans and economic well-being. These economic links are evident in the enduring and deep divides today between Black and White Americans in terms of income and wealth, as well as access to good healthcare and child care, equal education and housing, and criminal justice and environmental safety.

But first, the history—important not least because this week marks the beginning of Black History Month. While de jure racial discrimination at the polls is no longer tolerated—thanks, in part, to the 1965 Voting Rights Act—de facto discrimination, including facially neutral policies with disparate racial impacts, remain rampant. Take, for example, the widespread practice of states disenfranchising convicted felons. Only two states—Vermont and Maine, both with largely White populations—never take away felons’ right to vote, even while they are incarcerated. In the other 48 states, felons are subject to at least some voting restrictions, which have a profoundly disproportionate impact on Black Americans, who are targeted by the biased enforcement of drug laws and the country’s racist criminal justice system.

Black Americans are regular victims of overzealous and partisan purges of voter rolls, too. In Georgia, for example, a conservative estimate finds 198,351 voters were wrongfully deleted from the state’s voter rolls in a series of purges leading up to the 2018 elections, disproportionately disenfranchising young voters and voters of color on the erroneous grounds that they had moved residences.

How polling places are resourced and where they are located also have clear racial ramifications. According to an analysis by The Guardian, a new policy in Texas that allowed for widespread closure of polling locations disproportionately reduced access for Black and Latinx communities.

These examples just scratch the surface. Even if policymakers were to ignore the most egregious cases of targeted voter suppression, the universally applied bureaucratic barriers that make voting in the United States harder than in most other developed nations disproportionately disenfranchise Black Americans. Those barriers include a byzantine registration process and Election Day being held on a weekday during limited hours, both of which interact negatively with Black Americans—and low-income Americans of all races—who are less likely to have paid time off from work, are more transient in their place of residence, and are less likely to have stable transportation and child care arrangements.

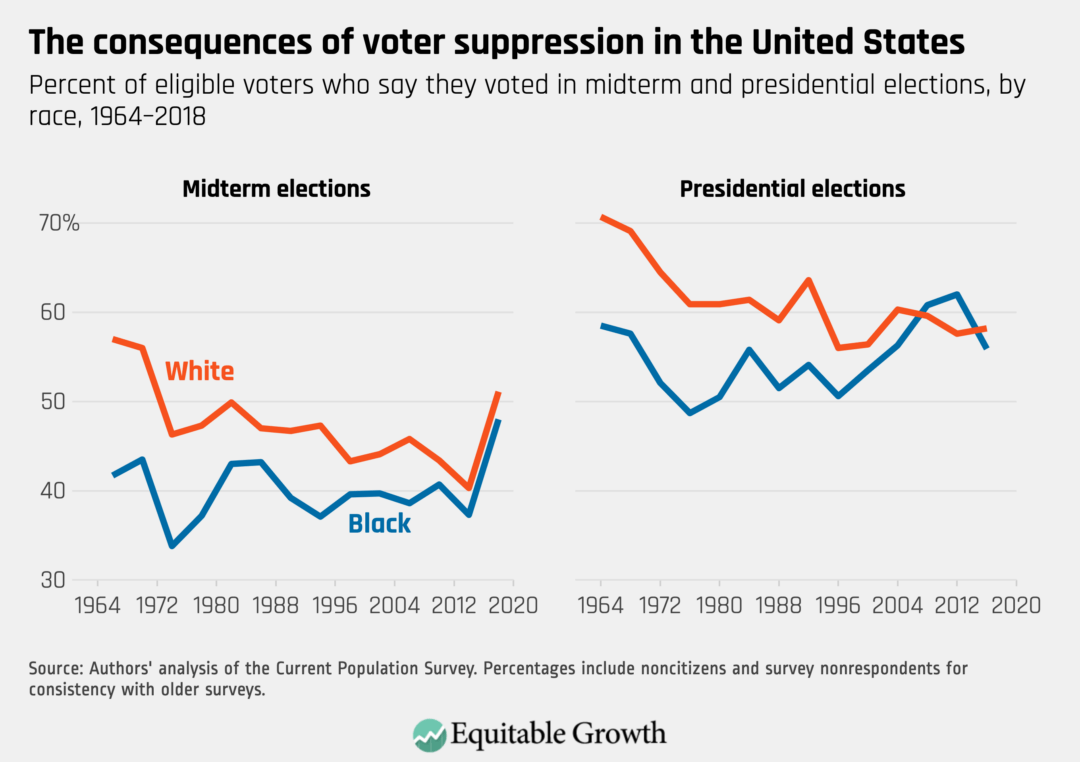

All of these economic barriers to voting are due to the ingrained structural racism in all U.S. laws, policies, and institutions, not just those related to voting, including discrimination and stratification in the labor market. Yet despite all these voter suppression barriers, turnout among Black Americans is relatively high, though it still often trails that of White Americans. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

As Figure 1 shows, the voting divide between White and Black Americans used to be wider. The aforementioned Voting Rights Act of 1965 cracked down on the worst abuses in the South, including poll taxes and literacy tests. In addition to boosting turnout among Black Americans almost overnight, the law presented a golden research opportunity, offering what academics call a “natural experiment” that can be exploited to test various hypotheses.

One such hypothesis is the claim we referenced earlier: that political inequality at the polls directly translates into economic inequality. This argument makes intuitive sense—to get reelected, politicians must be responsive to their voters’ preferences, and as the electorate gets more racially and economically diverse, politicians will pursue policies that deliver broader economic well-being. Yet it is hard to prove. In a democratic republic, it can be difficult to draw a straight line from voting behavior to policymaking, given the large number of mediating factors, from lobbyist strangleholds to gerrymandered districts.

But a number of recent papers looking at the Voting Rights Act help untangle this morass, making clear that expanding Black Americans’ political power indeed results in stronger economic standing as well. Giovanni Facchini and Cecilia Testa at the University of Nottingham and Brian Knight at Brown University find that the Voting Rights Act reduced the rate of Black arrests in jurisdictions where the chief law enforcement officer is elected, not appointed. The authors conclude that when Black Americans have the ability to vote for their sheriff, they are more likely to receive improved treatment by the criminal justice system—an important factor in shaping labor market outcomes.

Similarly, economists Elisabeth Cascio at Dartmouth College and Ebonya Washington at Yale University find that Southern counties with higher shares of Black Americans as residents experienced greater increases in both voter turnout and state investments in institutions and government programs important to Black citizens, compared to otherwise-similar counties, in the 20 years after the Voting Rights Act banned literacy tests.

Abhay Aneja, a law professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and finance professor Carlos Fernando Avenancio-León at Indiana University Bloomington (both Equitable Growth grantees) find that counties where voting rights were more strongly protected under the Voting Rights Act experienced larger reductions in the wage divide among Black workers and White workers between 1950 and 1980. The main reason seems to have been expanded access to public-sector jobs—jobs that White politicians had previously doled out almost exclusively to their White constituents without fear of electoral retribution. Other potential explanations for the result include fiscal redistribution, affirmative action, and anti-discrimination laws.

Of course, the opposite can also be true. As voter suppression tactics succeed in blocking access to the polls, economic inequality worsens. In a follow-up piece to their earlier study, Aneja and Avenancio-León found that the 2013 Supreme Court decision in Shelby County v. Holder, whicheffectively nullified major parts of the Voting Rights Act—and which was quickly followed by a resurgence in race-based voter suppression—exacerbated the wage divide between Black and White workers. A historical paper looking at Black disenfranchisement during the Jim Crow era of enforced segregation found that voting restrictions resulted in reduced teacher-child ratios in Black schools and lower wages for Black workers, in part because politicians had no incentive to make productive investments in Black communities.

These studies help give lie to the assertion, often espoused by “free-market” adherents, that economics is a naturally occurring phenomenon and that government can do little to address the growing threat of income and wealth inequality. In truth, those with political power determine the rules governing the U.S. economy, which means racial inequality in the nation’s electoral system is itself a major source of the enduring racial income and wealth divides. And as other researchers demonstrate, racial economic inequality can obstruct the supply of talent and slow innovation, hurting overall U.S. economic growth.

Like so many other American institutions throughout the nation’s history, the U.S. electoral system is continually subverted by those in power to perpetuate racial inequality, deepening both economic and democratic injustice. But unequal access to the polls, and the economic disparities that follow, are not immutable laws of our democracy. Tireless activism and a diversifying electorate paved the way, for example, for the 2021 election of Georgia’s first Black U.S. senator, Rev. Raphael Warnock.

But there are a number of evidence-backed steps policymakers can take to crack down on race-based voter suppression tactics that Black and low-income Americans still have to overcome. These solutions include reinstating the Voting Rights Act, making voter registration automatic, ending the disenfranchisement of former felons, and turning Election Day into a federal holiday. Many of these proposals and more were recently proposed by Democrats in the U.S. House of Representatives as part of the pro-democracy For the People Act.

For more on how policymakers can equalize access to the polls and ensure the U.S. electorate is truly representative of the country’s economic and racial diversity, read our new Equitable Growth report, “The consequences of political inequality and voter suppression for U.S. economic inequality and growth.”