Gross Domestic Product sets the tone of the U.S. economic debate while leaving working- and middle-class families behind

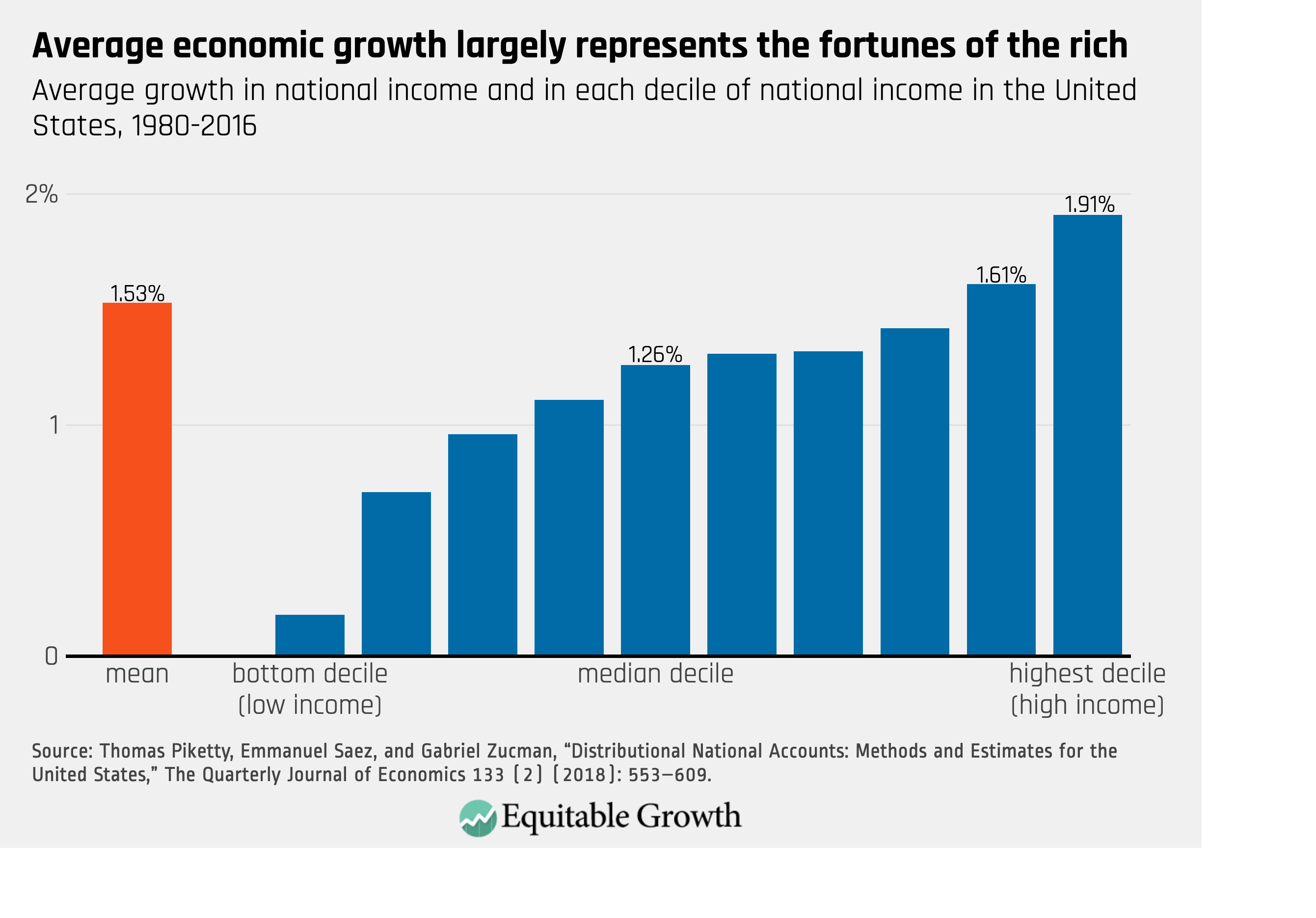

In a now-infamous incident in 2016, social scientist Anand Menon of King’s College London was discussing the economics of Brexit at a public forum. Upon noting that Brexit was likely to lead to declines in the United Kingdom’s Gross Domestic Product, a heckler called out “That’s your bloody GDP, not ours!” The heckler was crude but essentially correct—GDP is no longer reflective of the fortunes of most people. Rising inequality has created separate economies for the rich and poor: Across the globe, aggregate measures of growth tend to track the fortunes of the former, particularly in the United States. (See Figure 1.)

Now, new research from four political scientists shows that reporters continue to treat GDP growth as a critical metric of economic progress despite the disconnect between the metric and the welfare of most Americans. Because GDP growth most closely reflects rising incomes among the rich, the result is that economic news is most positive when the rich are benefitting. By contrast, the tone of economic news is unrelated to the economic fortunes of middle-income and low-income individuals and their families when top-income growth is accounted for. This research emphasizes the need for new measures of economic progress that more accurately capture progress for people at all levels of income. Equitable Growth has advocated for GDP 2.0, which would break aggregate growth into quintiles or deciles so we could see growth not just on average but also for working- and middle-class Americans.

To see how newspapers cover economic progress, the researchers collected stories about the economy from 32 major U.S. newspapers and used automated sentiment analysis to assign a positive or negative tone to each article, ranging from 1 (positive economic news) to -1 (negative economic news). The resulting measure shows the tone of economic reporting over three-month periods beginning in 1980. And while this measure of tone is closely correlated with the fortunes of the top 1 percent of income earners, it is uncorrelated with income growth in the bottom four quintiles.

In fact, the four researchers—Alan Jacobs of the University of British Columbia, J. Scott Matthews of Memorial University of Newfoundland, Timothy Hicks of the University College London, and Eric Merkley of the University of Toronto—further show that tone mostly follows the fortunes of the top 10 percent of income earners. And this shapes how people view the U.S. economy—the researchers find that people’s responses to questions on the Survey of Consumer Attitudes about economic performance closely track the tone of the news. Survey respondents are more likely to say that business conditions are good, that they had heard favorable economic news, and that the government is doing a good job of managing the economy when the news tone is positive.

Why do reporters seem to follow the fortunes of the rich in reporting good news? The authors argue it is not because journalists are biased or ideological. Instead, it is simply because over time, journalists have learned to use major economic aggregates such as GDP growth or stock market indices to track the state of the economy. And these statistics tend to reflect the fortunes of the rich, as shown in Figure 1.

This research demonstrates how ostensibly neutral decisions about how economic progress is defined can have profound consequences for the economic narratives presented in the news. Because GDP growth is released frequently and prominently and has a long history as an important indicator, journalists rely on it, and the consequence is that the American public is led to believe that the economy is good when, in fact, it may only be good for a narrow slice of people at the top of the heap.

Luckily our statistical agencies are working to address the disconnect between GDP and the economic fortunes of Americans at the middle and lower end of the income distribution. A new BEA release, for which a prototype will be released this week, would report personal income growth for Americans in each decile of the income distribution. So, instead of knowing only that overall growth was, say, 2 percent, we would also have data on the growth experienced by those in the middle of the income distribution or those at the bottom.

If reporters continue to rely on GDP growth as an important measure of economic progress, then they will be misinforming the public. Rising inequality has given the lie to the old expression “a rising tide lifts all boats.” GDP growth does not necessarily reflect a good economy for all or even most Americans. To align the U.S. government’s headline measurements of economic progress with the real fortunes of American families, federal agencies must begin to report on growth and other outcomes up and down the income spectrum.