Measurement matters. An equitable economy is impossible without it.

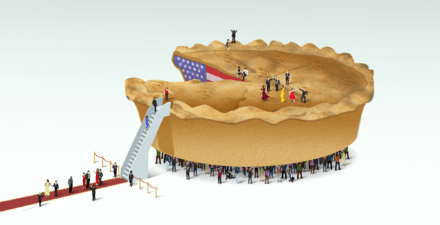

“What we measure affects what we do. If we measure the wrong thing, we will do the wrong thing. If we don’t measure something, it becomes neglected, as if the problem didn’t exist.” That’s the bottom-line message of a new report from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development that recommends changes in how nations measure their economic progress and the well-being of their citizens. Equitable Growth has long argued that many of our topline economic statistics are doing a poor job of measuring the welfare of citizens. As a first step to remedying the problem, Gross Domestic Product growth should be disaggregated so that each report tells us to whom growth is accruing. Academic analyses of federal tax data show that economic growth is too often benefitting only those at the top of the wealth and income ladders, leaving working- and middle-class Americans behind.

Advocating for one federal agency to generate a couple of new numbers may strike many readers as inconsequential, the kind of technocratic window dressing that will do nothing, in itself, to address the challenges posed by rising economic inequality. But as the OECD report makes clear, the policies that governments implement are influenced by the data available to them and by the data that dominate public discourse.

This lesson is plain from our experience in the United States. A few key economic statistics dominate our discussion of economic progress. Chief among them is GDP growth. The value of growth is an article of religious faith for most politicians and the political press. Small wonder that presidential candidates promise specific growth targets if they are elected and trumpet gains in GDP as proof of their success. But these conversations are often misguided. They often overlook the fact that not all GDP growth is the same and, moreover, that GDP growth in the aggregate means little for any individual person. In fact, GDP growth could be rising while the majority of workers see stagnant incomes. That we nonetheless pay so much attention to it is proof of the agenda-setting power of government statistics.

The impact is not simply rhetorical. What we measure has a strong impact on policy. Consider the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017. The bill’s sponsors promised strong growth gains from the cuts, and critics engaged with this point specifically, arguing in many cases that these claims were unrealistic, and that the actual contribution to growth would be low. But GDP growth really isn’t the right metric at all. The core analytic tools necessary for evaluating a tax cut, as Equitable Growth pointed out at the time, are distribution tables and revenue estimates. Distribution tables provide estimates of the change in economic well-being that results from tax legislation for people at different income levels.

Moving “Beyond GDP,” as the OECD report’s title suggests, is a significant challenge. Economists need to agree on what the right metrics are and how to calculate them. But U.S. policymakers can move ahead on some reforms now. Earlier this year, Sens. Charles Schumer (D-NY) and Martin Heinrich (D-NM) and Rep. Carolyn Maloney (D-NY) introduced bills in their respective chambers of Congress to task the Bureau of Economic Analysis with providing distributional estimates of GDP growth. Rather than one GDP growth estimate, this legislation would require estimates for Americans in each decile of income and would further break out gains made by those in the top 1 percent. Passage of the bill would fulfill “Recommendation 6” of the OECD report. In addition to refocusing the public and policymakers on the need for broad-based growth, these statistics may help economists diagnose weaknesses in the economy earlier and respond to them better. The OECD report persuasively suggests that having better statistics might have prompted a better policy response to the Great Recession worldwide.

But we will also have to train politicians and pundits to stop paying attention solely to GDP, which is increasingly divorced from the experience of everyday Americans in this age of widening inequality. The additional complexity of tracking a range of growth numbers instead of one need not be terrifying. If anything, it is terrifying that one-number economic barometers devised in the 1950s still guide our actions, despite their declining relevance to the economic fortunes of average Americans.