Getting cash transfer payments to recipients faster boosts household spending and stimulates the economy

Cash transfer programs are a widespread economic policy tool often used to stimulate spending or encourage savings among consumers. The United States most notably uses direct cash payments as part of its fiscal stimulus programs during economic downturns, such as during the Great Recession of 2007–2009. More recently, the federal government paid more than $850 billion directly to U.S. households during the coronavirus pandemic through three rounds of economic impact payments between March 2020 and March 2021.

Yet these programs that send money directly to households are relevant in other economic contexts aside from acute economic crisis. More than 130 countries around the world use direct cash payments as part of their social infrastructure and anti-poverty programs. Additionally, many developed economies are considering so-called universal basic income policies, which would send cash payments to households on a regular basis.

Whether the goal is to alleviate poverty or encourage consumer spending, our new working paper shows that the success of these programs depends on when households actually receive the funds. Using real-world data from two widely different cash transfer programs, we examine whether the timing of one-time cash transfer payments relative to when they are publicly announced has large impacts on household consumption behavior.

Our study demonstrates that household spending does not merely depend on the size of the transfer but also on the amount of time households anticipate receiving their payment. We find that in both developing and developed country settings, households scheduled to receive cash transfers earlier are more likely to spend and less likely to save, compared to those who receive cash transfers later.

Below, we explain the methodology behind our working paper and its findings, before detailing its implications for policy design.

The timing of cash transfers impacts household consumption and savings behavior

Standard economic theory says that households may respond to “unanticipated” payments by increasing their spending patterns, but should respond little, if at all, to the arrival of “anticipated” payments. This suggests that households spend more when they receive an unexpected cash transfer but do not necessarily increase their spending if the payment was previously publicly announced.

The effectiveness of widely publicized, previously announced fiscal stimulus payments, however, suggests that this story is incomplete. Studies show that households still increase their spending upon receiving a payment even if they know about it in advance. What effect, then, does the amount of time that households spend waiting for the cash to arrive have on their spending decisions?

Our working paper seeks to answer this question by comparing two cash transfer scenarios that played out in different economic contexts. We look at data from both the 2008 U.S. economic stimulus payments that were disbursed amid the financial crisis of 2007 and the ensuing Great Recession, as well as data on the distribution of one-time cash transfers in randomized controlled trials in Kenya and Malawi.

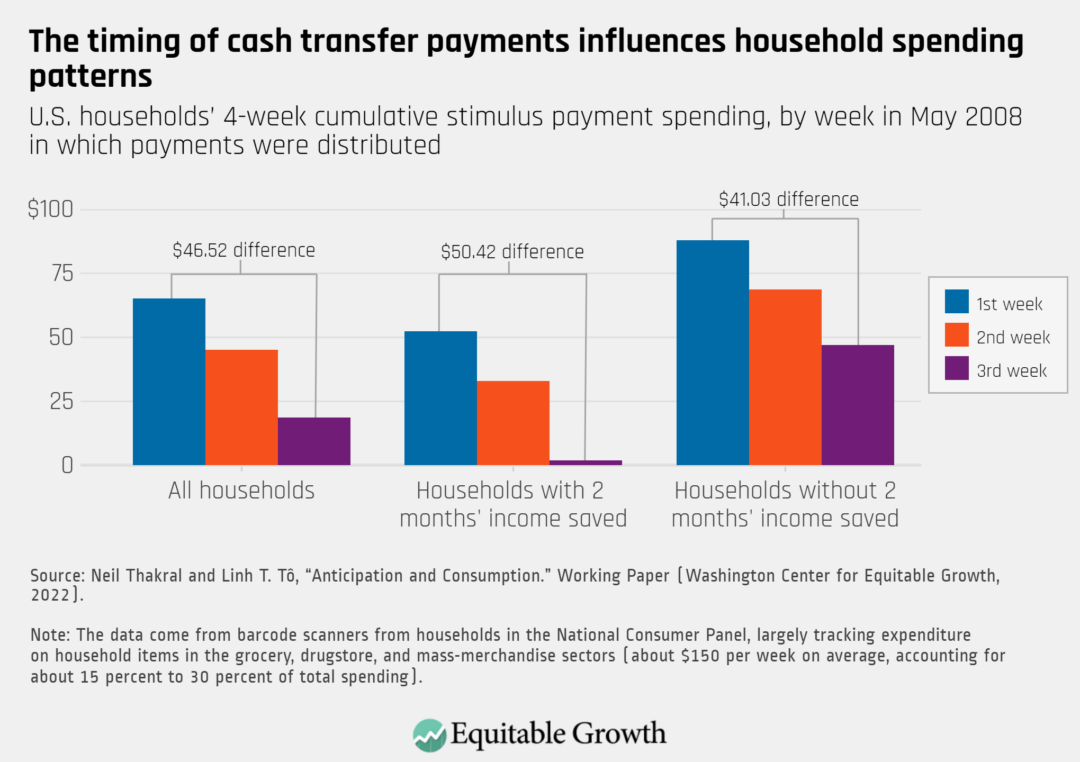

In the first scenario, the timing of federal government tax rebates sent to low- and middle-income households in the United States during the Great Recession was based on the last two digits of the recipient’s Social Security Number. Over a 3-month period starting in May 2008, checks were sent out to households, which also received written notice from the IRS several days prior to their payment dates. We utilize this to compare weekly spending habits across similarly situated households receiving transfers in different weeks. Specifically, we look at three groups who received checks in the first, second, and third weeks of May. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

As Figure 1 shows, the spending response for households in each of the three groups receiving transfers differs across different weeks. Households randomly assigned—Social Security Numbers are effectively assigned at random—to receive payments at the earliest-possible date had double the spending increase over the 4 weeks after receiving their rebate, compared to the average household. In fact, we find that an additional 1 week of waiting for a transfer decreases the propensity to spend that transfer as much as would increasing the size of the transfer by $340. This suggests that the timing of payments plays an important role in their effectiveness at boosting spending.

We then examine the relevance of liquidity, or whether a household has at least 2 months of income available either in cash, a bank account, or otherwise accessible in case of an unexpected decline in income or increase in expenses. As seen in Figure 1, we find that these divergent spending habits by payment timing remain across households regardless of their liquidity status. While households that do have some available savings tend to spend less out of their stimulus payments and save more than those that do not have savings, the households with savings that received their payment at the earliest possible date spent about as much as households without savings that had to wait an extra 2 weeks to receive their payments.

Turning to the second scenario and context of our study, we analyze data from existing randomized controlled trials distributing one-time cash payments to households in Kenya and Malawi. These programs were not instituted as a response to economic crisis, as seen in the U.S. scenario, but rather as part of randomized controlled trials by researchers and nongovernmental organizations to understand the impact of cash transfers on households in poverty.

We find that the differential spending behavior by the timing of the transfer delivery seen in the U.S. context holds in these two other settings as well. In other words, we find that shorter waiting times between payment announcement and receipt led to increases in household spending rates, while those households that experienced delays in payments increased their total household savings rates.

Implications for designing cash transfer program policies

The results of our working paper have implications for designing cash transfer programs intended to boost consumer spending, as well as those that aim to alleviate poverty. Taken together, the data and our model suggest that a payment delay of even just 1 week can have a large impact on how much of that payment a household spends versus saves—an important distinction for policymakers, depending on their broader economic priorities.

Our study suggests, for instance, that households treat large, one-time payments, such as stimulus checks, differently from a smaller series of regular transfers. Researchers have argued that large payments tend to feel more like wealth and less like disposable income, so households may save more of a large lump-sum payment and spend more of a series of smaller payments. Yet in 2009 and 2010, when the United States implemented a series of small transfers to households with the Making Work Pay Tax Credit, these payments were only half as effective in stimulating U.S. household spending, compared to the one-time stimulus payments in 2008.

Our model addresses this tension by highlighting the crucial role of anticipation and timing. The unexpectedly diminished effectiveness for consumption of the smaller series of payments in 2009 and 2010 can be explained by the fact that households had more time to anticipate receiving those transfers, thus shifting their focus to saving rather than spending.

Getting money urgently to low-wage U.S. workers

March 30, 2020

This implies that different household responses to both the size of a payment and how and when it is distributed must be taken into account when determining a policy’s effectiveness. Household spending behavior following one-time transfers, for instance, might not be an accurate indication of the efficacy of universal basic income policies—which tend to be smaller and delivered on a monthly basis rather than in one larger lump-sum—for reducing poverty.

Our findings also indicate that policymakers must consider their ultimate goals—boosting spending or building wealth—when designing the disbursement of cash transfers. If increasing consumption is the top priority, then cash payments should be rapidly sent out to households with little notice of their arrival. If longer-term investments and savings are the goal, however, then policymakers should consider providing more advance warning of the impending payments to households.

—Neil Thakral is an assistant professor of economics and international and public affairs at Brown University and the Watson Institute. Linh T. Tô is an assistant professor of economics at Boston University.