Factsheet: What the research says about taxing pass-through businesses

In recent years, so-called pass-through businesses have taken center stage in a number of crucial tax policy debates. This large and growing category of U.S. business—which includes sole proprietorships, partnerships such as law firms, private equity companies, and hedge funds, and S-corporations such as retail stores, banks, and other private, closely held companies—receive special tax benefits. Pass-throughs also received a large, regressive tax break known as the qualified business income deduction, or the Section 199A deduction, as part of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017.

Why do these tax preferences exist for pass-through businesses? Are they justified? This factsheet dives into existing academic evidence on the rise of pass-throughs and how their lax regulation and low taxation contribute to U.S. income and wealth inequality, as well as efficiency losses that are a drag on overall U.S. economic growth. This factsheet also looks at opportunities for tax avoidance and evasion, which many pass-through owners take advantage of, draining critical resources from the public fisc.

Though this factsheet is focused on federal tax treatment of pass-throughs, it is important to note that state tax treatment can be different, including entity-level franchise fees, withholding requirements, and, more recently, the option of entity-level taxes in order to help pass-through owners circumvent the cap on the state and local tax deduction instituted in 2017.

First, let’s turn to the basics: What is a pass-through business?

What is a pass-through business?

All businesses in the United States that are not C-corporations are treated as “pass-throughs” for purposes of federal taxation. These businesses’ profits (and losses) are “passed through” to the owners, who pay taxes on the business via their personal income tax. C-corporations, in contrast, pay a corporate income tax at the entity level, and then C-corporation shareholders generally pay a second tax if and when they either sell their stock for a “capital gain” or receive a dividend.

The form the income takes when earned by the pass-through business—such as capital gains from investments and ordinary income from general business operations—remains intact when it flows to the owner’s personal tax return, meaning pass-through business owners often pay different tax rates on their different types of income and, for ordinary income, face the progressively structured individual income tax.

Pass-through businesses are able to take many of the same tax deductions to which C-corporations are entitled, such as write-offs for employee wages, equipment depreciation, investment in research and development, and other miscellaneous expenses such as business-related meals. But owners of pass-through businesses must pay tax on their businesses’ incomes in the year that they are earned, even if that income is never actually distributed to owners. Allowing business owners to indefinitely defer tax on undistributed profits, as owners of C-corporations are generally allowed to do, would incentivize inefficient “capital lock” and turn pass-through structures into tax shelters.

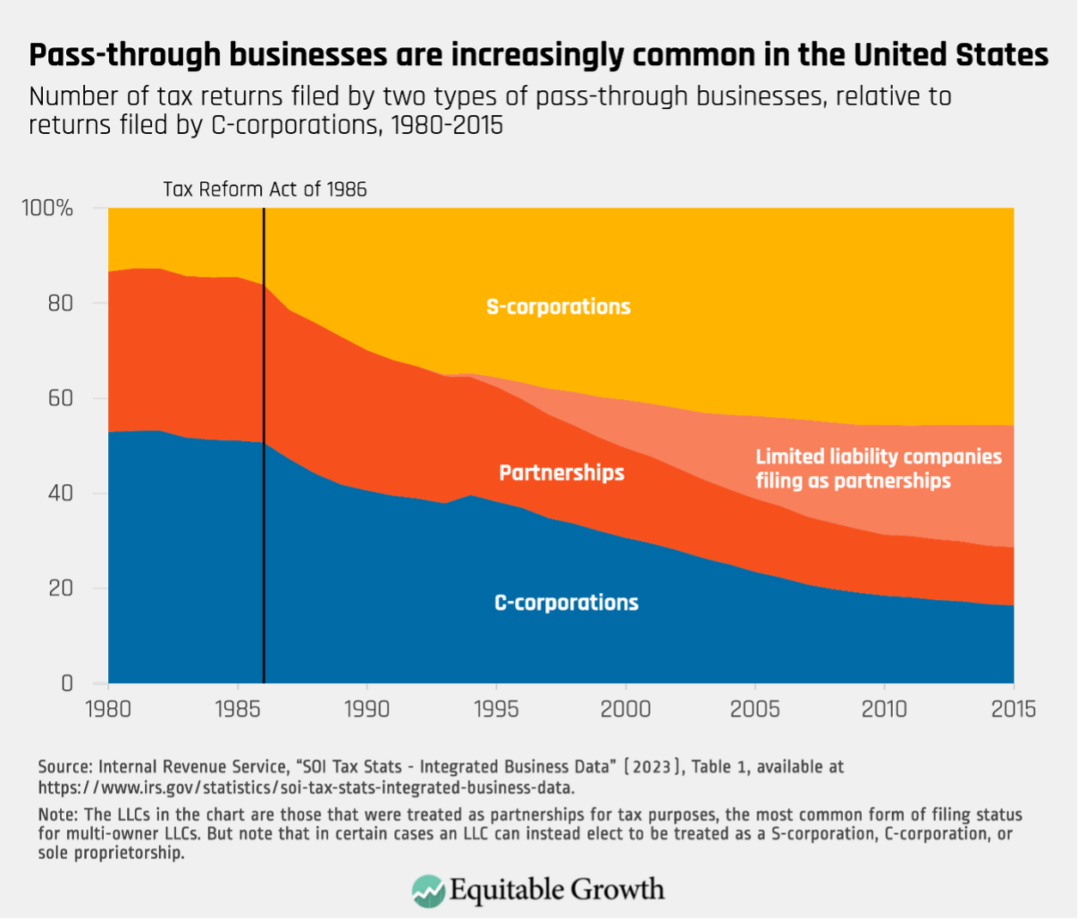

Since the 1986 tax reform bill—which made pass-throughs more attractive by drastically lowering individual tax rates—pass-throughs have become by far the most popular business type in the United States. In 1985, 51 percent of business tax returns, not including sole proprietorships, were filed by C-corporations; in 2015, that figure had plummeted to 16 percent. Pass-throughs have made up the difference, exploding in popularity in part because of the advent of limited liability companies in the 1990s, which, in their multi-owner form, are usually treated as partnerships for tax purposes. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

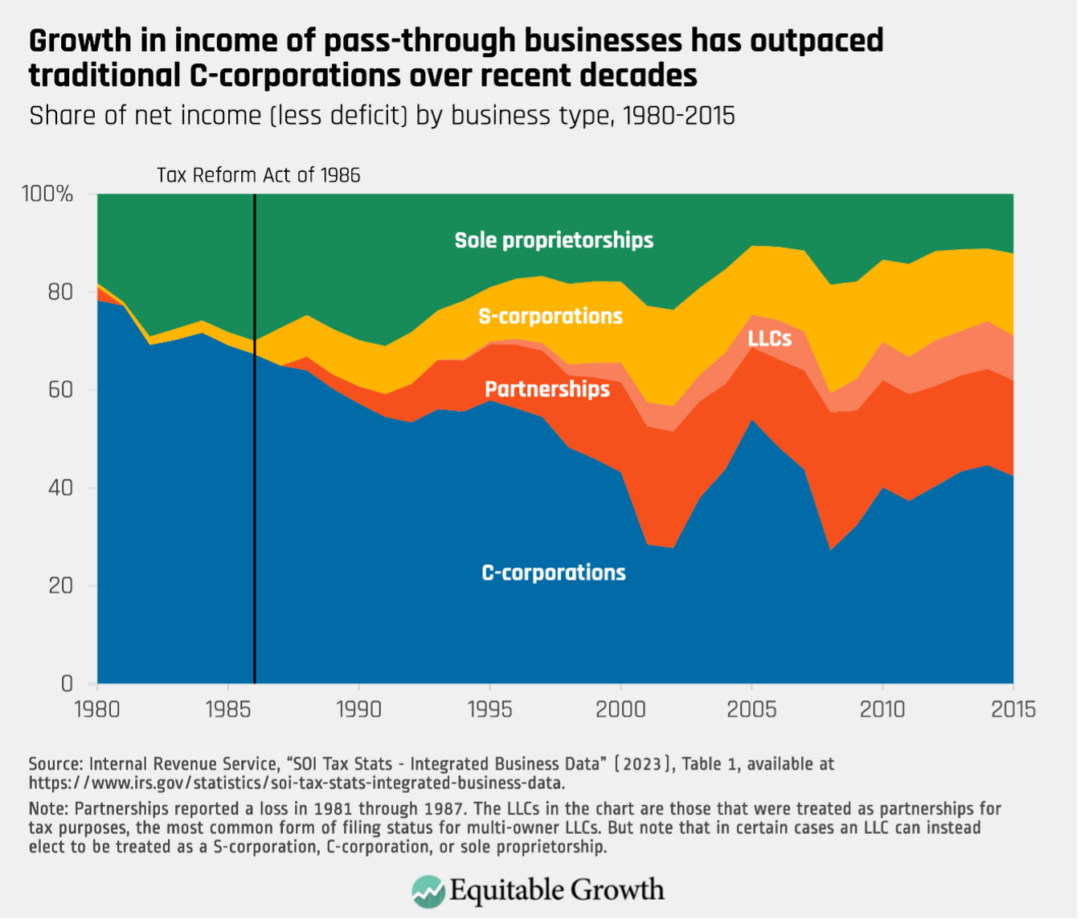

According to tax records—which are probably providing underestimates—pass-throughs earned $1.57 trillion in total net income in 2015.1 That income was generated by 33.4 million tax units, or 95 percent of all business returns. By comparison, 1.6 million C-corporations2 earned a total of $1.15 trillion in net income that same year. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

In 2021, pass-throughs employed 43 percent of the U.S. workforce and 35 percent of total U.S. payroll.3 The United States is an outlier in its widespread use of pass-throughs: It ranks second among the advanced-economy member nations of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development for share of noncorporate businesses at 15 percentage points above the OECD average, which does not include S-corporations, since those are technically still a corporate legal form.

What are the different types of pass-through businesses?

There are three main types of pass-through businesses: sole proprietorships, S-corporations, and partnerships.4 Limited liability companies are usually treated as partnerships for federal tax purposes or, if they have only a single owner, as a sole proprietorship, referred to by tax practitioners as a disregarded entity5

Sole proprietorships

A sole proprietorship is a business run by a single individual or a married couple.6 These businesses generally pay income tax on their business earnings via Form 1040 Schedule C of their owners’ individual tax returns. The types of businesses that file as sole proprietorships are quite varied and include lawyers, contractors, taxi drivers, insurance agents, home healthcare workers, and restaurateurs. Indeed, in 2021, the most popular sectoral classification for sole proprietorships was “other services,” which includes personal and laundry services and auto repair and maintenance, among many others.

There are a lot of sole proprietors in the United States, but they tend to be very small in terms of total income and assets, compared to other business types. In 2021 (the most recent year for which the IRS has released data), there were 29.3 million sole proprietor returns with a total net income of just $411 billion (averaging roughly $14,000 of income per sole proprietor).7 In 2020, sole proprietor profits amounted to 21 percent of total business receipts.

S-corporations

S-corporations have a larger number of shareholders than sole proprietorships, but no more than 100 owners. All owners must be U.S. individuals holding the same class of stock, not foreigners or other business entities. The firms most likely to file as S-corporations are in professional, scientific, and technical services (16.3 percent), construction (13 percent), or real estate and rental and leasing (11.2 percent).8

In 2017 (the most recent year for which the IRS has released complete data), there were 4.7 million S-corporation returns.9 In total, these businesses declared $578 billion of net income and held $4.5 trillion in assets.10

Partnerships

Unlike S-corporations, shareholders of partnerships need not be individuals, but instead can be corporations or other partnerships, which themselves can have other corporations and partnerships as shareholders. Partnerships can also easily switch to C-corporation status should that become advantageous, whereas it is much more difficult for C- and S-corporations to change into partnerships.

Many different types of businesses are treated as partnerships for tax purposes, including limited liability companies (71.7 percent of all partnerships in 2021), general partnerships (12.6 percent), limited partnerships (9.9 percent), and limited liability partnerships (3.2 percent).11 More than half of partnerships are in the real estate and rental and leasing sector, but partnerships in the finance and insurance sector earn the most total net income and hold the most assets.

In 2021, the most recent year for which the IRS has released complete data, there were 4.5 million partnership returns declaring a total of $3.89 trillion in net income.12 In 2019, partnerships held a whopping $36 trillion in assets. One analysis of 2017 IRS data estimates that partnerships earned more than one-third of reported business income that year.

Are all pass-through businesses “small”?

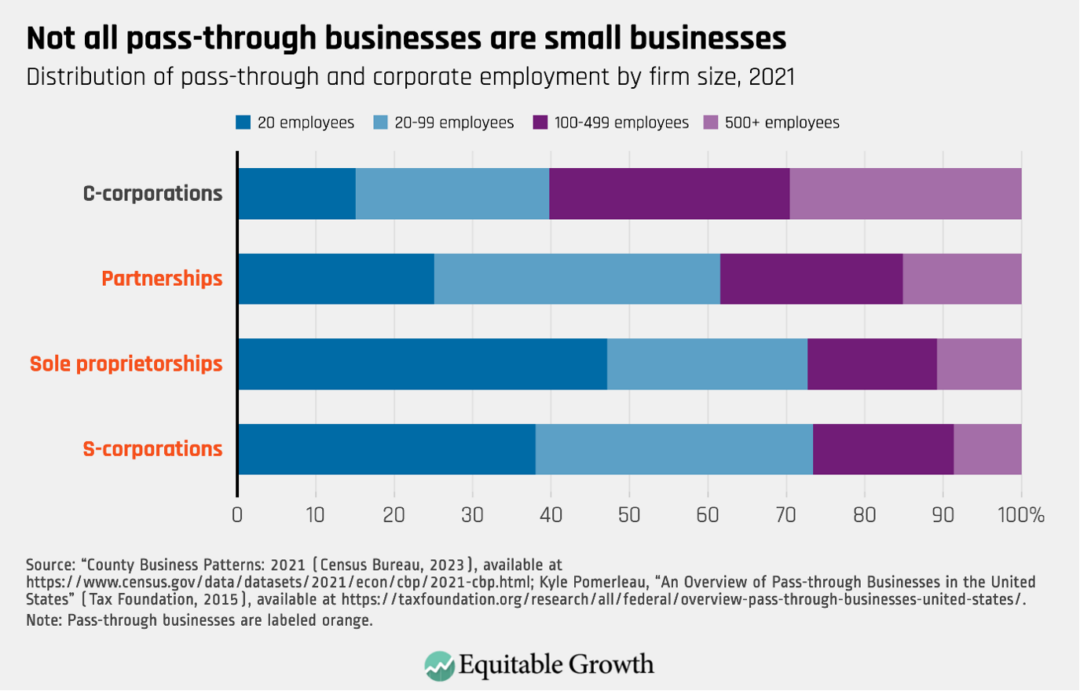

This is a common misconception. While pass-through businesses tend to be smaller both in terms of their number of employees and earnings than C-corporations, there are several exceptions. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

In fact, some of the most profitable firms in the United States, even including some publicly traded companies, are pass-throughs.13 Activist investor Carl Icahn’s conglomerate Icahn Enterprises, for example, is a publicly traded partnership, as is the gas pipeline behemoth Energy Transfer. Indeed, many oil and gas companies are structured as master limited partnerships, a special form of pass-through business. And, as various investigative reports have revealed, many large and highly profitable privately held companies—including ABC Supply Co. (roofing), Bechtel (engineering), Blackstone Group (finance), Bloomberg (media), Carlyle Group (finance), Georgia-Pacific (paper), Fidelity Investments (finance), Kinder Morgan (energy), KKR (finance), MidFirst Bank (finance), Oaktree Capital Management (finance), Pretium Partners (real estate), RMR Group (real estate), StoneMor (funeral services), certain Trump Organization companies (real estate), Uline (packaging), and WeatherTech (auto supplies)—are pass-throughs.

This hasn’t stopped pass-throughs from claiming “small business” status in political debates, exploiting the fact that there is no universally accepted definition of “small.”14 But when U.S. Treasury Department researchers attempted to estimate the number of legitimately small business entities in 2010, they identified 22.2 million pass-through filers,15 which is just more than half of all pass-through returns that claim some business activity.16 These bona fide small businesses account for just 26 percent of net pass-through business income, and only 4 million of them, or fewer than 1 in 5, employ any workers.17 This means that, in 2010, just 1 in 4 dollars in pass-through net income was earned by a bona fide small business, and fewer than 1 in 10 pass-throughs were both legitimately small and employed even a single worker.

In 2010, just 1 in 4 dollars in pass-through net income was earned by a bona fide small business, and fewer than 1 in 10 pass-throughs were both legitimately small and employed even a single worker.

Why are pass-throughs advantageous from a tax perspective?

One major reason pass-throughs have grown in popularity is their tax treatment.18 While C-corporations face both an entity-level tax (the corporate income tax of 21 percent) and a shareholder-level tax on dividends (20 percent if “qualified” and received by a high-income investor) and capital gains (20 percent if sold by a high-income investor after holding longer than one year),19 pass-throughs only face one level of tax. This tax has historically been lower than the combined C-corporation rate, even for those owners in the highest marginal income tax rate bracket (currently 37 percent).20

In fact, one analysis of partnerships in 2011 estimated that those businesses face an average effective tax rate of just 15.9 percent, largely because partnerships in the finance sector can classify much of their income as capital gains and can deduct various expenses and losses. Considering that the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 lowered taxes for pass-through firms, this number is likely even lower today.

How does the rise of pass-throughs contribute to U.S. economic inequality?

Owners of pass-through businesses tend to be White, male, and older—demographic groups that already earn more than their non-White, female, and younger peers. They also tend to be high-wealth individuals: In 2023, it is estimated that 20 percent of the top 1 percent’s total assets are in “private businesses,” a category that largely overlaps with pass-throughs. This amounts to 53 percent of all private business assets.21

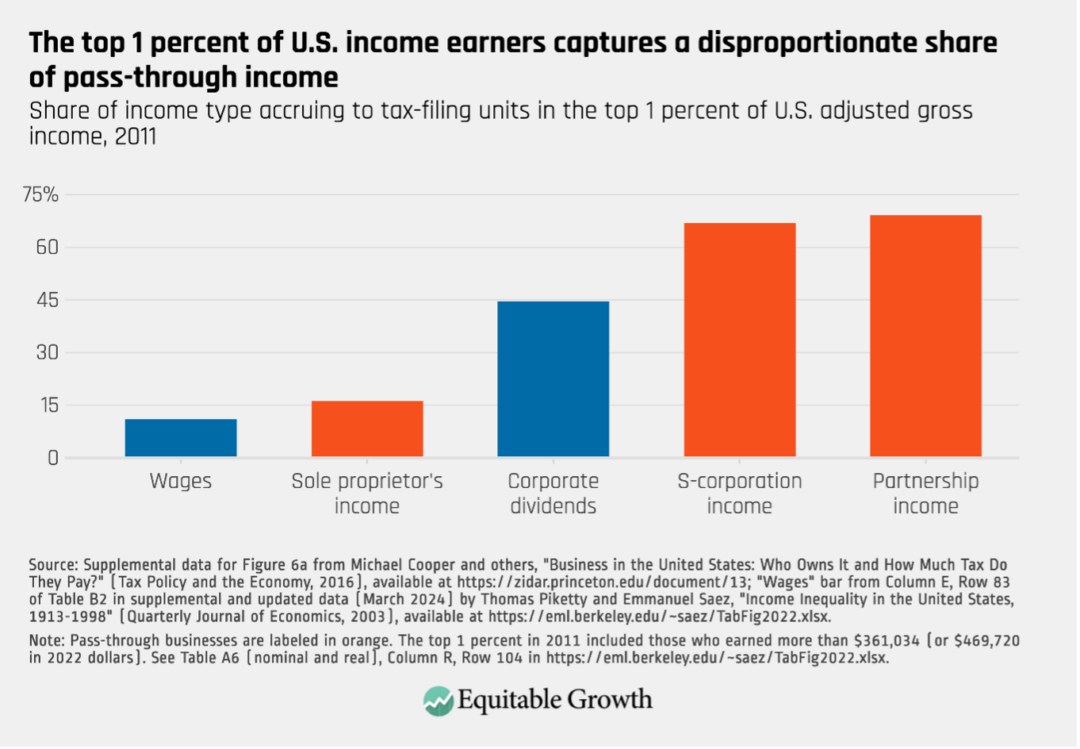

Pass-through owners not only tend to come from wealthy backgrounds but also tend to have high incomes. A Congressional Research Service analysis from 2011 finds that 63 percent of pass-through income was earned by taxpayers with an adjusted gross income higher than $250,000, and 32 percent was earned by individuals with an AGI of more than $1 million. The Joint Committee on Taxation estimates that the top 0.01 percent earned 35 percent of its total income via pass-throughs in 2019, whereas the bottom 90 percent received just 9 percent of its income via pass-throughs. An academic analysis of 2011 tax returns finds that 69 percent of partnership income and 67 percent of S-corporation income accrued to the top 1 percent (those making more than $361,034) that year.22 (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

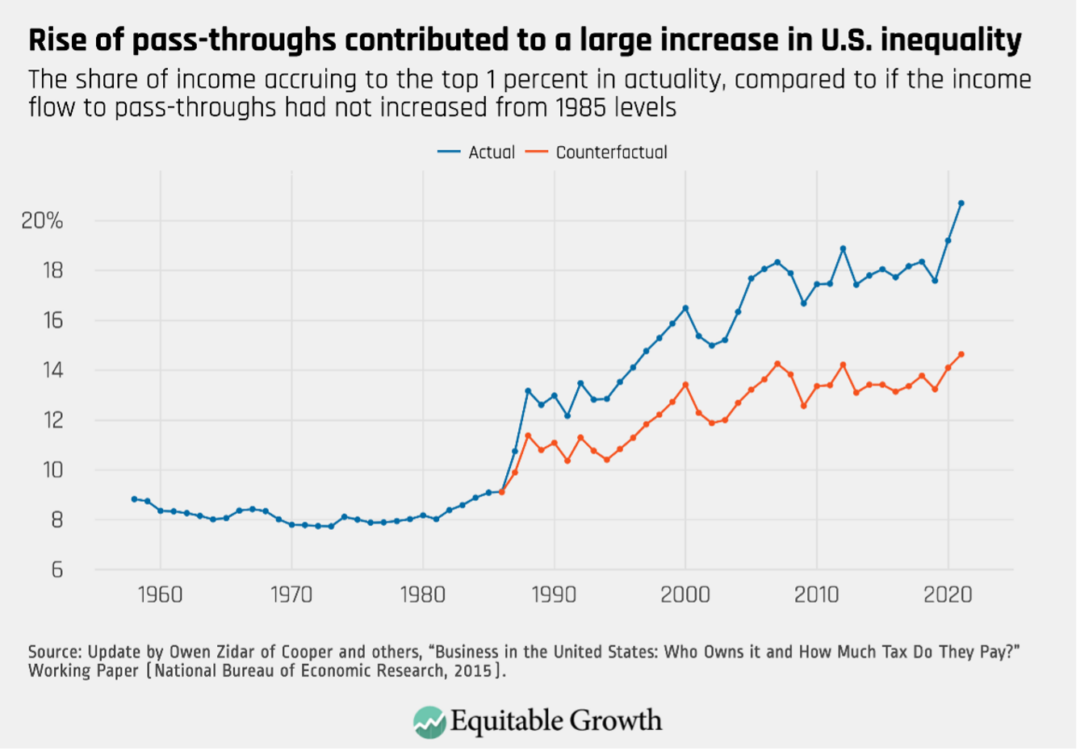

Before 1986, most profitable firms were organized as C-corporations. After the tax reform of 1986, however, rich business owners began converting to—or began new firms as—pass-throughs to take advantage of the lower tax on owners.

Not surprisingly, then, the rise of pass-throughs has contributed to an explosion in income inequality in the United States, as the rich earn more and pay less in taxes. One rigorous analysis from researchers at Princeton University, the University of Chicago, the University of California, Berkeley, and the U.S. Treasury Department finds that 52 percent of the increase in the income share going to the top 1 percent between 1985 and 2021 came in the form of higher pass-through business income.

In other words, if pass-through income had stayed at its 1985 level, the top 1 percent’s income share would be up just 5.55 percentage points, compared to 1985, from 9.09 percent to 14.64 percent. Instead, the top income share skyrocketed 11.61 percentage points over that period, from 9.09 percent to 20.7 percent. (See Figure 5.)

Figure 5

Another study from 2019 finds similar results, noting that the pass-through-fueled increase in U.S. inequality is not simply a matter of the form in which the income happens to be generated and reported on tax returns, but also the result of real economic phenomena, including reduced overhead costs for pass-throughs, higher fractions of profits being distributed to pass-through owners, and riskier investments taken on by pass-throughs (to compensate for a less diversified capital raise), compared to C-corporations.23

How has the rise of pass-throughs undermined tax enforcement and contributed to tax avoidance and evasion?

Pass-throughs can be complicated legal structures, and current tax law allows pass-throughs many opportunities for game-playing to reduce federal tax burdens. The result is low audit rates and high levels of tax avoidance and potential evasion.

Take, for example, partnerships. Eighty-five percent of partnerships are simple structures owned by individual taxpayers. But the other 15 percent are highly complex and opaque, using multi-tiered ownership webs that are difficult for tax authorities to trace.24

Partnerships also take advantage of lax rules around partner contributions of capital or labor to the business, as well as allocations—how tax gains and losses are distributed—to engage in sophisticated tax planning.25 Two classic examples of this are:

- The now well-documented “carried interest” loophole, which allows partners of investment firms to be paid for services in the form of long-term capital gains rather than wages, reducing high-income partners’ income tax rate and completely eliminating their self-employment tax liability.

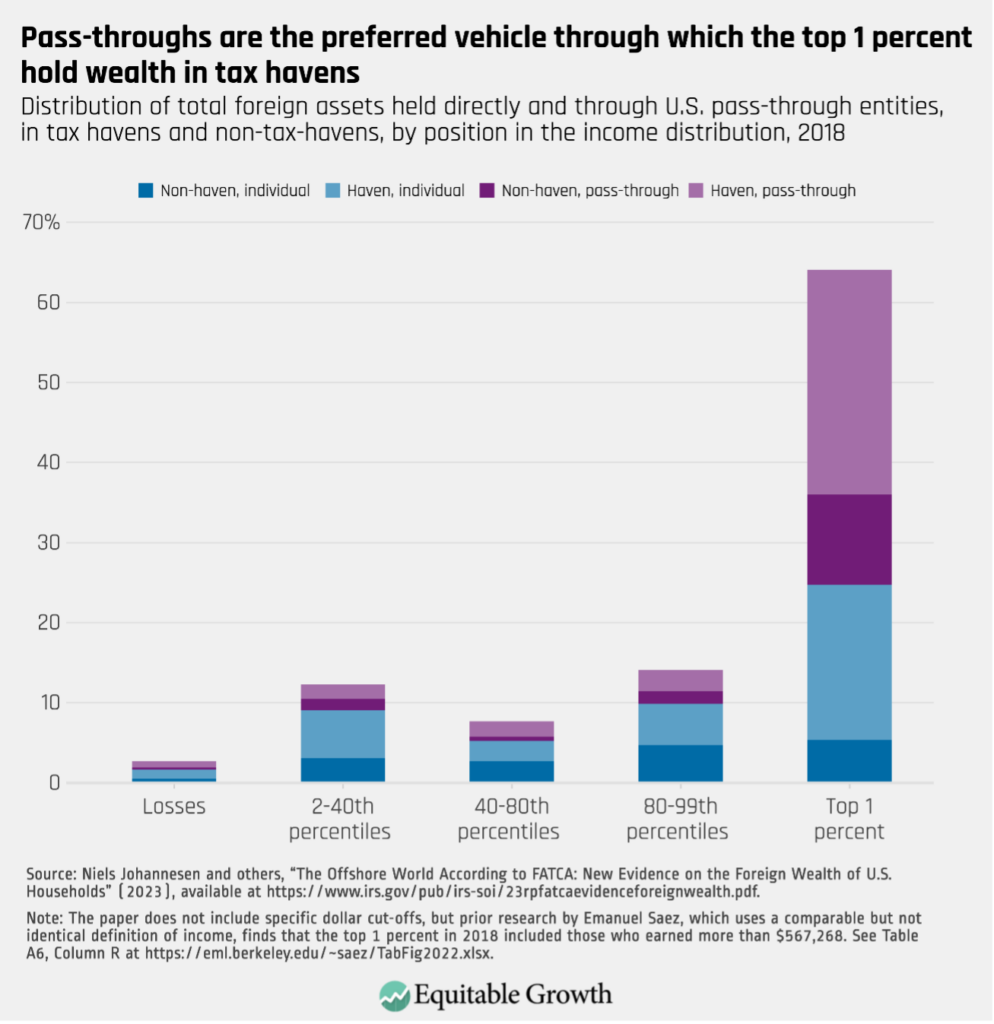

- So-called blocker corporations in tax havens, through which partnerships, particularly private equity firms and hedge funds, can funnel money to shield foreign investors from filing and paying U.S. taxes and to prevent tax-exempt investors, such as pension funds and university endowments, from paying unrelated business taxable income.26 These schemes are powered in part by highly flexible “check the box” rules that allow business entities to choose their organizational form for tax purposes. The same firm can select partnership status for the United States and corporate status for a foreign jurisdiction. This is likely one of the reasons why one recent study using new data from the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act, or FATCA, finds that partnerships are the preferred vehicle through which excessively rich Americans hold wealth in tax havens. In fact, 64 percent of U.S.-owned foreign wealth is held by the top 1 percent, 61 percent of which is funneled through pass-throughs. (See Figure 6.)

Figure 6

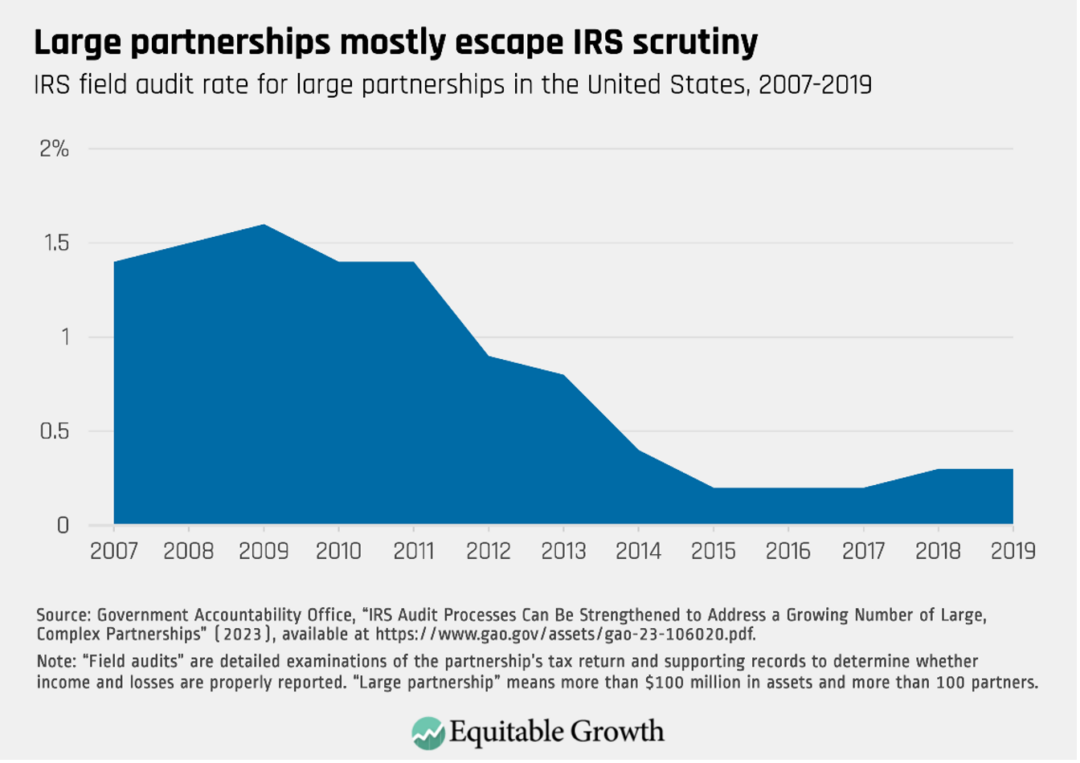

These findings are consistent with other evidence that tax evasion is prevalent among large,27 complex partnerships, which are very rarely audited by the IRS.28 (See Figure 7.)

Figure 7

New audit procedures that went into effect in 2018, alongside additional funding for the IRS as part of the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, may close some of these enforcement gaps.29 One promising enforcement tactic is the use of sophisticated machine-learning, nonlinear models to identify potential underpayment. Academics have shown that these approaches are superior to traditional linear prediction models at identifying tax evasion by partnerships.

S-corporations are also problematic from a tax compliance and enforcement standpoint. Many service companies, such as law firms and doctors’ offices, often miscategorize their owners’ labor income as business income to avoid self-employment taxes.30 Famously, former U.S. Sen. John Edwards (D-NC), former U.S. Rep. Newt Gingrich (R-GA), and President Joe Biden have all taken advantage of this loophole. Self-employment taxes help pay for Medicare and Social Security, so this ploy drains resources from those critical social insurance programs.31 Limited partnerships are also able to play this game, though it’s not as straightforward and has been the subject of tougher IRS scrutiny.32

Similarly, sole proprietorships are likely underpaying taxes, according to reports from the Government Accountability Office and IRS.33

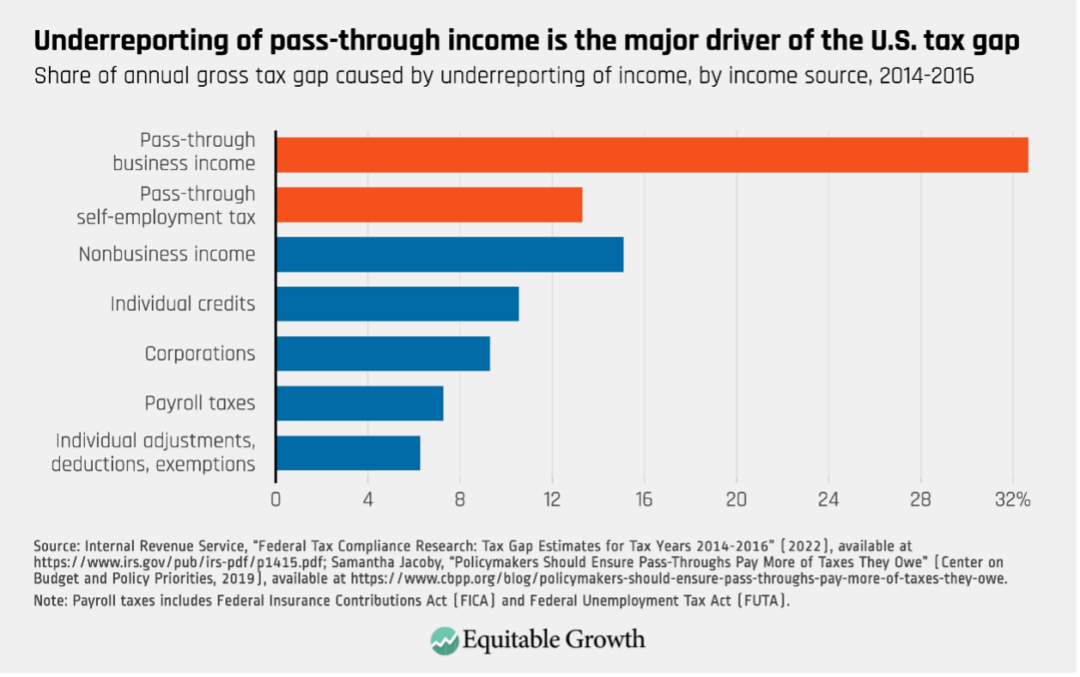

All of the above examples highlight why the underreporting of pass-through income is believed to be the single biggest driver of the tax gap, or the difference between what taxpayers owe the IRS and what they voluntarily pay on time. (See Figure 8.)

Figure 8

How has the rise of pass-throughs affected the overall U.S. economy?

Low tax rates on rich business-owners and loophole-laden tax regulations for pass-throughs are not just bad for equality and tax compliance, but also for the overall U.S. economy. It means fewer resources are available to invest in productivity- and growth-enhancing public programs, such as universal child care, high-quality public education, and green technologies.

In addition to draining the federal government of much-needed resources, this trend toward pass-throughs has negative efficiency effects, keeping businesses artificially small and capital constrained. This is because most pass-throughs are not able to be listed on public stock exchanges, putting them at a disadvantage in terms of raising capital. Some academic researchers have modeled this effect, including:

- Katarzyna Bilicka and former AEA Summer Economics Fellow at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth Sepideh Raei, both from Utah State University, find that eliminating the artificial tax difference between C-corporations and pass-throughs, while keeping total revenue collected constant, would boost aggregate economic output by 1.3 percent due to a more efficient allocation of capital as the most productive firms choose to be C-corporations rather than pass-throughs.

- Sebastian Dyrda from the University of Toronto and Benjamin Pugsley from University of Notre Dame estimate that the Tax Reform Act of 1986 pushed the most productive firms—and those firms with the richest active owners—to pass-through status, leading each firm to reduce its employment growth by an average of 1.86 percentage points, reducing employment across the U.S. economy by 0.8 percent and reducing aggregate output by 1.1 percent.34 The same authors also helpfully point out that more than three-quarters of all pass-through establishments are nonemployers, belying claims that pass-throughs are engines of job growth.

- Daphne Chen from Econ One Research, Inc., and Shi Shao Qi and Don Schlagenhauf from Florida State University find that funneling productive businesses toward the pass-through structure also probably costs the economy jobs because C-corporations are less capital-constrained and can thus do more hiring.

- A separate study from Florida State’s Qi and Schlagenhauf looked at a policy in Kansas that eliminated the state tax on pass-through income, concluding that the reform likely led more businesses to organize as pass-throughs instead of C-corporations, which would explain the reduced output, reduced capital formation, and reduced employment growth experienced after the reform took effect in the state.

There also is an efficiency cost to the amount of time, effort, and money that goes into pass-through tax planning. Many investment funds, for example, expend considerable expense to set up multiple partnerships and blocker corporations to maximize tax savings. The cost of these activities, which serve no real business purpose and could be better spent on any number of other productivity-enhancing endeavors, are what economists call deadweight loss.

How can policymakers improve the taxation of pass-throughs?

There are strong efficiency, fairness, and anti-evasion arguments for equalizing the tax treatment of different business forms. Complete harmonization between C-corporations and pass-throughs, which would require a substantial rewrite of the tax code, is unlikely in the near term.

Even so, some more immediate policy actions could include:

- Fully funding enforcement efforts at the IRS

- Closing the “carried interest” loophole, something the most recent Biden administration budget proposes35

- Closing self-employment tax loopholes, also something the most recent Biden administration budget proposes36

- Allowing Section 199A—a large, unjustified tax break for pass-through business owners—to expire as scheduled at the end of 2025

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the invaluable assistance I received in writing this factsheet from Karen Burke, Jason DeBacker, Sebastian Dyrda, Zorka Milin, Gregg Polsky, Kyle Pomerleau, Daniel Reck, and Owen Zidar. All errors are my own.

Did you find this content informative and engaging?

Get updates and stay in tune with U.S. economic inequality and growth!

End Notes

1. Author’s calculations from Table 1 in IRS, “SOI Tax Stats—Integrated Business Data,” available at https://www.irs.gov/statistics/soi-tax-stats-integrated-business-data, removing regulated investment companies and real estate investment trusts, both of which can be treated as pass-throughs in certain instances but are outside the scope of this factsheet. Similarly, Anmol Bhandari and Ellen R. McGrattan, “Sweat Equity in U.S. Private Business.” Working Paper 24520 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2020), available at https://www.nber.org/papers/w24520, finds that pass-throughs accounted for 57 percent of post-audit business net income between 2004 and 2014.

2. The most recent IRS Data Book reports that there were 2.5 million C-corporation returns filed in 2023, a 9 percent increase from the year prior, but those figures are not associated with income information and are not perfectly comparable to historical findings, so they were not included in Figures 1 or 2. See Table 2 in IRS, “Internal Revenue Service Data Book, 2023,” available at https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p55b.pdf.

3. Author’s calculations from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2021 County Business Patterns database, available at https://www.census.gov/data/datasets/2021/econ/cbp/2021-cbp.html. Pass-throughs represented by S-corporations, sole proprietorships, and partnerships. Non-pass-throughs includes C-corporations, government entities, and nonprofits but excludes “other,” since that (small) category probably includes some establishments that are treated as pass-throughs, such as trusts, estates, and cooperatives.

4. The other types of tax entities that sometimes get pass-through status but are outside the scope of this factsheet are sole proprietor farming businesses, regulated investment companies, real estate investment trusts, cooperatives, estates, and certain other trusts.

5. The “C” in C-corporation and the “S” in S-corporation are references to their respective subchapters in the Internal Revenue Code. Partnerships are governed by Subchapter K of the Internal Revenue Code.

6. This is a reference to “nonfarm” sole proprietors. There is a separate tax classification (and a separate schedule, Schedule F) for sole proprietors with farm income, which are treated as a special kind of pass-through for tax purposes. Only 1.9 million taxpayers filed as farm sole proprietors in 2015, the latest year for which IRS has released data. See IRS, “SOI Tax Stats—Historical Table 21a,” available at https://www.irs.gov/statistics/soi-tax-stats-historical-table-21a.

7. IRS, “SOI Tax Stats—Integrated Business Data,” Table 1, available at https://www.irs.gov/statistics/soi-tax-stats-nonfarm-sole-proprietorship-statistics.

8. IRS, “SOI Tax Stats—Integrated Business Data,” Table 6.1, available at at https://www.irs.gov/statistics/soi-tax-stats-s-corporation-statistics#basictables.

9. The most recent IRS Data Book reports that there were 5.9 million S-corporation returns filed in 2023, a 5.3 percent increase from the year prior, but those figures are not associated with income information and are not perfectly comparable to historical findings, so they were not included in Figures 1 or 2. See Table 2 in IRS, “Internal Revenue Service Data Book, 2023,” available at https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p55b.pdf.

10. IRS, “SOI Tax Stats—Integrated Business Data,” Table 2.4, available at https://www.irs.gov/statistics/soi-tax-stats-s-corporation-statistics#basictables. But note that net income calculations for S-corporations are likely understatements because they do not include owners’ labor income, a type of earnings that sole proprietors and partnerships do report as net income on tax returns. C-corporation net income figures may also be understatements for the same reason. See Susan C. Nelson, “Paying Themselves: S Corporation Owners and Trends in S Corporation Income, 1980–2013.” Working Paper 107 (U.S. Department of the Treasury: Office of Tax Analysis, 2016), available at https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/131/wp-107.pdf

11. IRS, “SOI Tax Stats – Partnership Statistics by Entity Type,” Table 9a, available at https://www.irs.gov/statistics/soi-tax-stats-partnership-statistics-by-entity-type. The other two types are foreign partnerships (0.7 percent of the total number of partnership filings that year) and entities that select the “other” box or did not check any box on Form 1065 (1.8 percent).

12. IRS, “SOI Tax Stats – Partnership Statistics by Entity Type,” Tables 9a and 9b, available at https://www.irs.gov/statistics/soi-tax-stats-partnership-statistics-by-entity-type. The most recent IRS Data Book reports that there were 5.1 million partnership returns filed in 2023, an 11.7 percent increase from the year prior, but those figures are not associated with income information and are not perfectly comparable to historical findings, so they were not included in Figures 1 or 2. See Table 2 in IRS, “Internal Revenue Service Data Book, 2023,” available at https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p55b.pdf.

13. Some publicly traded partnerships are treated as C-corporations for tax purposes, but PTPs, as they are known, can get more attractive partnership tax treatment if more than 90 percent of their income is from passive investments or certain natural resource development. Sophisticated tax planners, however, have figured out how to “launder” nonqualifying income through blocker corporations, allowing private equity firms and even cemetery operators to win the exemption. See John D. McKinnon, “More Firms Enjoy Tax Free Status,” Wall Street Journal, January 10, 2012, available at https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052970203733504577026361246836488.

14. Even the U.S. Small Business Administration often varies its thresholds by industry (between $1 million and $35.5 million in sales, and between 50 employees and 1,500 employees).

15. This includes sole proprietors, partners, and S-corporation shareholders (and those taxpayers who declare farm or rental income) with less than $10 million of annual income or deductions. It does not include the additional 1.4 million small businesses that filed as C-corporations. Nor does it include pass-through owners who are not really operating a business under the common use of that word, such as misclassified workers who are forced to file a business return to pay tax as independent contractors, hobbyists who misclassify costs associated with their pastime as business losses, partnerships that offer no goods or services to the marketplace but are purely passive investment vehicles, and infrequent renters of a vacation home or others with de minimis business activity.

16. There were 42.9 million pass-through returns with some business activity in 2010.

17. Net income calculations are extracted from Richard Prisinzano and others, “Methodology to Identify Small Businesses.” Technical Paper 4 Update (U.S. Department of the Treasury Office of Tax Analysis, 2016), available at https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/131/TP4-Update.pdf. See Tables 1b (all filers net income minus C-corporation all filer net income) and 2b (small business net income minus C-corporation small business net income). Employers are identified by having more than $5,000 in direct labor deductions (wage-salary expenses).

18. In addition to lower taxes, other legal developments over the past three decades made pass-throughs more attractive to business owners, including the advent of the limited liability corporation, or LLC, in the 1990s, which allowed easy limited liability for all owners that had previously only been available to C-Corporation shareholders; “check-the-box” rules from the late 1990s that made it easier for business entities to choose the most beneficial tax category; and the liberalization of the rules governing S-corporations. See IRS, “LB&I Concept Unit Knowledge Base – International (Washington: U.S. Department of the Treasury, n.d.), available at https://www.irs.gov/pub/int_practice_units/ore_c_19_02_01.pdf.

19. Note that many shareholders of C-corporations are exempt from investor-level tax on account of their nonprofit status, such as university endowments, or tax-deferred status, such as shares held in an Individual Retirement Account, or foreign status. See Steve Rosenthal and Theo Burke, “Who’s Left to Tax? US Taxation of Corporations and Shareholders” (Washington: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, 2020), available at https://www.law.nyu.edu/sites/default/files/Who%E2%80%99s%20Left%20to%20Tax%3F%20US%20Taxation%20of%20Corporations%20and%20Their%20Shareholders-%20Rosenthal%20and%20Burke.pdf. They find that only roughly one-fourth of all U.S. corporate stock is taxable at the investor level.

20. This is not always the case and will depend on idiosyncratic characteristics of the business, including the extent to which the firm, if organized as a C-corporation, plans to retain its earnings rather than distribute dividends (thus reducing the immediate tax liability facing shareholders); the administrative burden of allocating profits and deductions to passive investment partners each year, which is one reason venture capitalists seem to opt against partnership structures for their portfolio companies (see Gregg Polsky, “Explaining Choice-of-Entity Decisions by Silicon Valley Start-Ups,” Hastings Law Journal 70 (2019), available at https://digitalcommons.law.uga.edu/fac_artchop/1273/); the extent to which start-up investors want to be eligible for the qualified small business stock exclusion, a potentially lucrative—and regressive—tax break on the capital gains of early-stage C-corporations (see James R. Repetti, “The Impact of the 2017 Act’s Tax Rate Changes on Choice of Entity,” Florida Tax Review 2 (2018), available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3134794; Manoj Viswanathan, “Money for nothing: The Qualified Small Business Stock capital gains exclusion is a giveaway to wealthy investors, startup founders, and their employees” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2023), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/money-for-nothing-the-qualified-small-business-stock-capital-gains-exclusion-is-a-giveaway-to-wealthy-investors-startup-founders-and-their-employees/); and the extent to which pass-through business owners think the C-corporation rate cuts in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 will remain intact, since it is difficult to cheaply extricate assets after putting them into corporate form (see Penn Carey Law School, “New article by Knoll challenges the consensus that the 2017 tax reform bill incentivizes small business to incorporate” (2019), available at https://www.law.upenn.edu/live/news/9168-new-article-by-knoll-challenges-the-consensus-that).

21. Staff of the Joint Committee on Taxation, “Present Law And Background On The Income Taxation Of High Income And High Wealth Taxpayers” (Washington: U.S. Congress, 2023), Tables 6 and 7, available at https://www.jct.gov/getattachment/b2168cb1-1026-4e58-9f62-65802dddfa79/x-51-23.pdf.

22. Supplemental data for Figure 6a from Michael Cooper and others, “Business in the United States: Who Owns It and How Much Tax Do They Pay?,” Tax Policy and the Economy 30 (1) (2016), available at https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.1086/685594 (data available at https://zidar.princeton.edu/document/13). The top 1 percent in 2011 included those who earned more than $361,034 (or $469,720 in 2022 dollars). See Table A6 (nominal and real), Column R, Row 104 in https://eml.berkeley.edu/~saez/TabFig2022.xlsx.

23. In addition to contributing to the share of income going to the top 1 percent, the rise of pass-throughs also helps explain the decline in the corporate-sector value added accruing to labor in national accounts, a phenomenon that has long puzzled economists. See Matthew Smith and others, “The Rise of Pass-Throughs and the Decline of the Labor Share.” Working Paper 29400 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2021), available at https://www.nber.org/papers/w29400.

24. Partnerships also benefit from lax reporting requirements, making it more difficult for researchers—and IRS auditors—to confidently estimate their tax compliance. A recent judicial decision that the Corporate Transparency Act, which requires businesses, including pass-throughs, to report their ultimate owners to federal authorities, is unconstitutional will likely only complicate efforts in this area. See Kate Kelly, “Judge’s Ruling Sets Back Law Meant to Fight Money Laundering, The New York Times, March 3, 2024, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2024/03/03/us/politics/judge-ruling-corporate-transparenct-act.html.

25. See Emily Cauble and Greg Polsky, “The Problem of Abusive Related-Partner Transactions,“ Florida Law Review 16 (479) (2014), available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2526464, for just one example: the problem of “related-partner allocations,” which allow family members to game the loophole-laden “substantial economic effect” test while also not running afoul of the “partnership anti-abuse rule.” It appears former President Trump’s father made common use of this loophole. See David Barstow, Susanne Craig, and Russ Beuttner, “Trump Engaged in Suspect Tax Schemes as He Reaped Riches from His Father,” The New York Times, October 2, 2018, available at https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/10/02/us/politics/donald-trump-tax-schemes-fred-trump.html. Before he was president, Donald Trump himself also seems to have taken advantage of the lax partnership rules to take distributions of profits tax free. See Russ Beuttner, Susanne Craig, and Mike McIntire, “Long-Concealed Records Show Trump’s Chronic Losses and Years of Tax Avoidance, The New York Times, September 27, 2020, available at https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/09/27/us/donald-trump-taxes.html.

26. Conversely, many C-corporations embed pass-through entities in their ownership structure for tax avoidance reasons. See Ashish Agarwal, Shannon Chen, and Lilian Mills, “Entity Structure and Taxes: An Analysis of Embedded Pass-Through Entities,” The Accounting Review 96 (6) (2021), available at https://publications.aaahq.org/accounting-review/article-abstract/96/6/1/4359/Entity-Structure-and-Taxes-An-Analysis-of-Embedded?redirectedFrom=fulltext

27. The Government Accountability Office defines a large partnership as having $100 million or more in assets and 100 or more total partners.

28. How much high-income partners—and high-income owners of other pass-through businesses more generally—are underreporting income is a major battleground in the academic debate over the extent to which inequality has increased over time. See Austin Clemens, “New research does not overturn consensus on rising U.S. income inequality” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2024), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/new-research-doesnt-overturn-consensus-on-rising-u-s-income-inequality/.

29. See Initiative 3.3, “Expand enforcement for large partnerships,” in Internal Revenue Service, “Inflation Reduction Act Strategic Operating Plan: FY2023–2031” (2023), available at https://www.irs.gov/about-irs/irs-inflation-reduction-act-strategic-operating-plan. There also has been a more recent announcement that the IRS is in the process of standing up a special pass-through unit. See Kristen A. Parillo, “LB&I Eyes End of Fiscal Year Launch of Pass-Through Unit,” Tax Notes, March 26, 2024, available at https://www.taxnotes.com/tax-notes-today-federal/audits/lbi-eyes-end-fiscal-year-launch-passthrough-unit/2024/03/26/7jchx.

30. The current self-employment tax, which is designed to mimic the payroll taxes that are withdrawn from W2 workers’ paychecks, includes a 12.4 percent Social Security tax (up to a cap of $168,600 in 2024), a 2.9 percent Medicare tax (no cap), and an 0.9 percent additional Medicare tax (on income higher than $200,000 for single taxpayers and $250,000 for married joint filers). One corroborating piece of evidence comes from an analysis of firms that switch from C-corporation status to S-corporation status, finding that they immediately reduce reported labor payments and increase reported profits, likely a tax-motivated decision. See Smith and others, “The Rise of Pass-Throughs and the Decline of the Labor Share.”

31. S-corporations are technically limited in their ability to mischaracterize wages in this way because of a legal requirement that they pay “reasonable compensation” in the form of labor income, which is subject to self-employment tax, to owners who are active in managing the business. But given the subjective nature of “reasonableness” and the nontransparent nature of these firms, this rule is nearly impossible to enforce. Instead, S-corporation owners often pay themselves in the form of business profits, which are not subject to the self-employment tax. What makes this avoidance strategy particularly effective is that, thanks to a separate loophole, active S-corporation owners can also avoid the net investment income tax (a 3.8 percent tax meant to mimic the self-employment tax for high-income, passive investors) on those business profits by claiming that, while they are not working for the S-corporation, they are “materially participating” in the business. See Karen C. Burke, “Exploiting the Medicare Loophole,” Florida Tax Review 21 (2018), available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3431989.

32. As a general rule, general partners in limited partnerships must pay the self-employment tax on their share of the business’s income, as well as any “guaranteed payments” they receive for services rendered (a term of art connoting the equivalent of labor income). Yet pursuant to what’s known as the “limited partner exception,” limited partners only pay the self-employment tax on guaranteed payments, thus creating an incentive for general partners to be miscategorized as limited partners (as well as for LLC owners, called “members,” to claim limited partner status). But the IRS has been aggressively litigating against these uses of the limited partner exception, with some success. See Gibson Dunn, “Tax Court Determines That Limited Partners Are Not Necessarily Exempt from Self-Employment Tax – The Limits of the Limited Partner Exception, as Such,” December 19, 2023, available at https://www.gibsondunn.com/tax-court-determines-that-limited-partners-are-not-necessarily-exempt-from-self-employment-tax-limits-of-limited-partner-exception/. As in the S-corporation context, limited partners can also sometimes avoid the net investment income tax, which was intended to fill the self-employment tax gap for high-income, passive investors, by claiming material participation in the business. See Burke, “Exploiting the Medicare Loophole.”

33. This is likely because of a lack of an income withholding regime, which would make compliance with quarterly tax obligations easier; and a lack of third-party reporting on certain small payments, which would improve both compliance and enforcement efforts.

34. These are general equilibrium effects. The partial equilibrium effects are 1.2 and 1.5, respectively.

35. U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Treasury Greenbook” (2024), pp. 137–138, available at https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/131/General-Explanations-FY2025.pdf.

36. Ibid, pp. 73–75, available at https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/131/General-Explanations-FY2025.pdf.