Money for nothing: The Qualified Small Business Stock capital gains exclusion is a giveaway to wealthy investors, startup founders, and their employees

Overview

The Qualified Small Business Stock exclusion, enshrined in Section 1202 of the Internal Revenue Code, permits early-stage venture capital firms and angel investors in high-tech startups, those startups’ founders, and early employees to avoid paying any federal income tax on the capital gains from the eventual sale of early-issued shares in these firms. The QSBS exclusion, which was first enacted into law 30 years ago to promote the creation of these kinds of startups, has undergone major revisions since then. Today, the QSBS exclusion provides tax breaks to those who demonstratively need them the least.

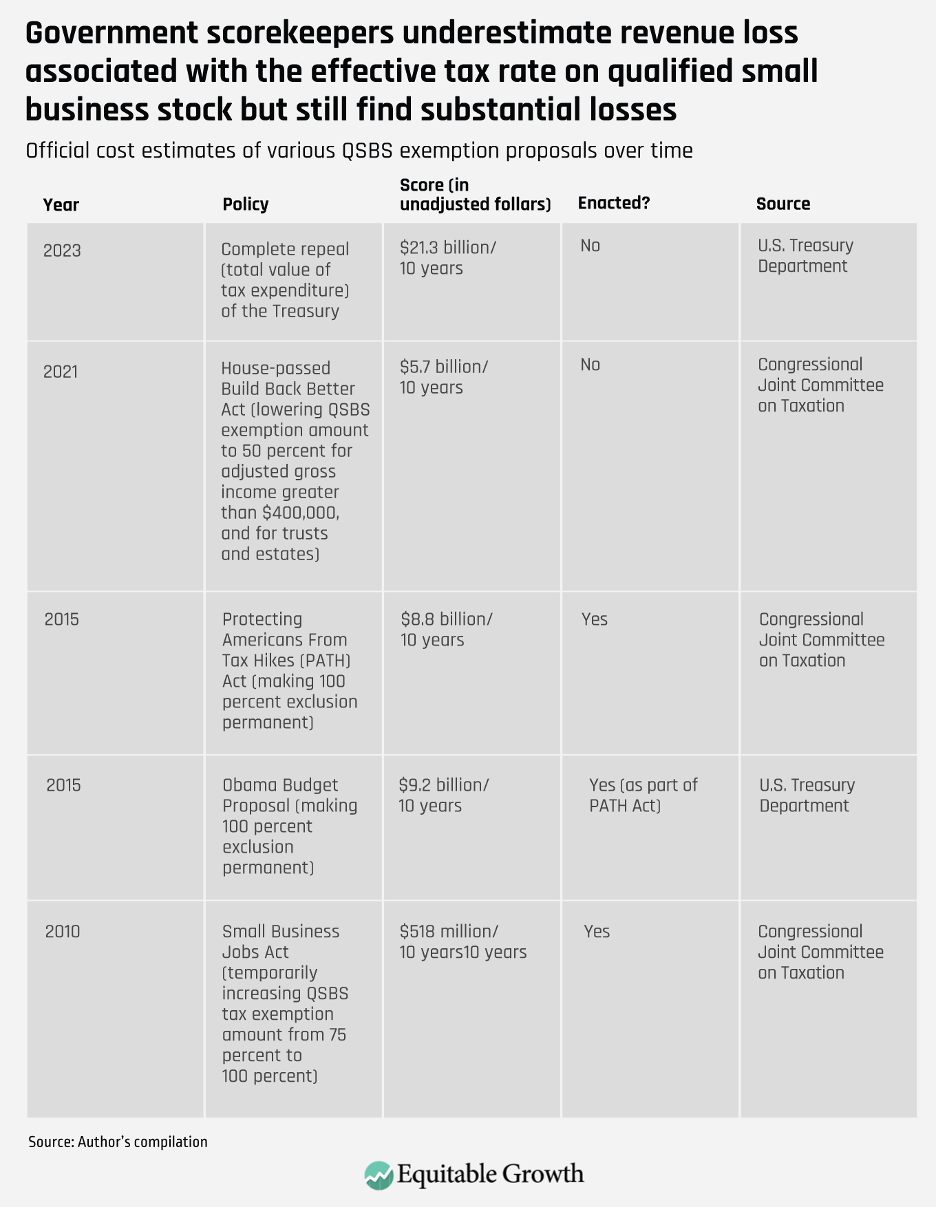

This unnecessary tax break costs the U.S. Treasury an estimated $2 billion to $3 billion a year in lost revenue now and well into the next decade. And those estimates may be seriously understated due to the opaque attributes of the public reporting on the use of the QSBS tax exclusion.

The QSBS exclusion today permits avoiding all taxes on capital gains arising from the sale of early-issued C-corporation stock—a narrow exclusion because more than 90 percent of small businesses in the United States (defined as having less than $10 million of annual revenue) are organized as something other than C-corporations.1 As a result, the QSBS exclusion exacerbates U.S. income and wealth inequality by targeting a tax break toward savvy and already wealthy high-tech investors and (often repeat) entrepreneurs who are perfectly willing to take risks with their money and time without any encouragement from the tax code.

This issue brief details the history of the QSBS exclusion to show how it became a vehicle for perpetuating income and wealth inequality. I then detail the extent to which the revenue losses associated with the QSBS exclusion are understated, perhaps significantly so. I then turn to potential options for reform, among them repealing Section 1202 of the tax code or amending it so that the sweeping 100 percent deduction available today is scaled back for taxpayers with excessively high incomes.

A brief history of the Qualified Small Business Stock exclusion

The U.S. Congress first considered the QSBS exclusion in 1989, when then Sen. John Kerry (D-MA) proposed exempting certain stock from preferential capital gains rates to incentivize “investors to put their money into small and developing businesses.”2 Although his version didn’t gain traction, by 1991 a bipartisan coalition including Kerry and then Sens. Al Gore (D-TN), Trent Lott (R-MS), and Arlen Spector (R-PA) were voicing support for similar legislation.3

The QSBS exclusion finally became law in 1993, which provided reduced capital gains rates on newly issued stock held for more than 5 years, issued by a C-corporation with less than $50 million of gross assets, and involved in an active business. This requirement excludes non-“qualified trades or businesses” such as banking, financing, leasing, and businesses involving the performance of certain skilled services.4

And as previously noted, because the QSBS exclusion limited the tax break to early stage C-Corporations, it in effect also ensured that other kinds of small businesses organized as limited liability companies, sole proprietorships, and S-corporations did not qualify for the tax break. This leaves more than 90 percent of small businesses in the United States (defined as having less than $10 million of annual revenue) ineligible for the tax break.5

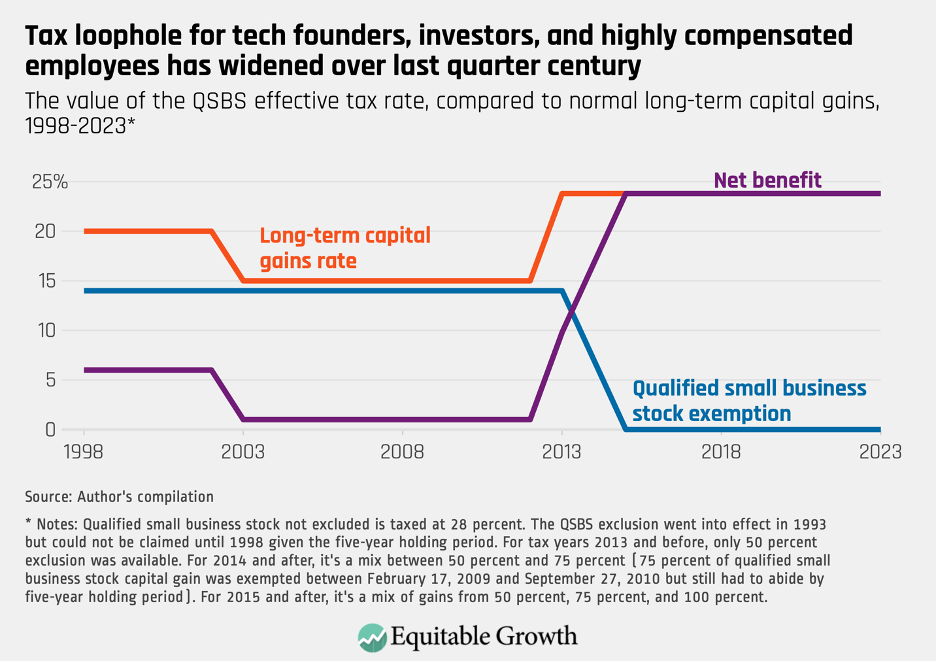

The value of the QSBS exclusion for its intended beneficiaries has waxed and waned since its initial enactment into law. Initially, 50 percent of qualified small business stock was exempted from federal tax, but the tax rate from the sale of qualified small business stock that was not excluded by Section 1202 was pegged at 28 percent, the top capital gains rate in 1993. This resulted in an effective qualified small business stock capital gains rate of 14 percent.

As capital gains rates changed over the years, decreasing to 20 percent in 1998 and to 15 percent in 2003, the tax savings associated with the QSBS exclusion, which still had an effective tax rate of 14 percent, decreased first to 6 percent and then to just 1 percent. With this small differential, the QSBS exclusion provided little by way of tax savings for early investors in young start-up firms, their founders, and early employees.

This changed significantly with the enactment of the Small Business Jobs Act of 2010. The newly updated statute temporarily increased the QSBS exclusion percentage to 100 percent and excluded qualified small business stock from any alternative minimum tax calculations.6 This meant the exclusion could still be used by taxpayers taking many other deductions and who pay very little in taxes overall. Because the top capital gains rate was now 23.8 percent, the benefit of the QSBS exclusion suddenly became very significant in terms of tax savings for its intended beneficiaries.

In 2015, these changes were made permanent. Taxpayers acquiring qualified small business stock after September 2010 now had assurance that $10 million (or ten times their initial investment, whichever was greater) of their capital gains, if realized at least 5 years after their investment, would be completely exempt from federal income taxes—and without any income-based restrictions on its use or explicit prohibitions on its use by trusts and estates. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Policymakers considered limiting the QSBS exclusion in 2021, when the U.S. House of Representatives passed the Build Back Better Act. The proposed legislation would have limited the QSBS exclusion to 50 percent (from 100 percent) for taxpayers with adjusted gross incomes of greater than $400,000, and for trusts and estates. The exclusion was never taken up by the U.S. Senate when parts of the Build Back Better Act were folded into the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, which left the QSBS exclusion untouched.

Who benefits from the Qualified Small Business Stock exclusion?

Qualified small business stock is typically obtained by three groups: the founders of start-up C-Corporations, their early employees, and early-stage venture capital firms and angel investors. Founders receive equity in exchange for their work in launching the company, known colloquially as “sweat” equity. The venture capital firms and angel investors (individuals wealthy enough to invest directly in young startups), and often individual venture capitalists and repeat tech entrepreneurs receive equity in return for providing that early-stage funding. And early employees receive equity in the form of stock options so long as they remain employed by the startup.

Additionally, Section 1202 potentially allows businesses worth billions of dollars to benefit from the exclusion. The reason: “Small” businesses under this law are permitted to have gross assets of up to $50 million and still qualify for the exclusion, but this limit refers to the amount of cash and “aggregate adjusted bases of property” held by the business, not to the actual valuation of the business.7 Thus stock issued by a company valued at, say, $200 million with minimal assets or property that has been completely depreciated (for tax purposes) could still potentially qualify for the QSBS exclusion.

Importantly, once stock is established as qualified small business stock, it retains that classification regardless of how large the business gets. The founders and early investors behind the creation of Uber Technologies Inc., for example, used the QSBS exclusion despite Uber’s valuation at its Initial Public Offering in 2019 of approximately $80 billion.

Achieving the purported benefits of the Qualified Small Business Stock exclusion

There is limited recent work into whether the QSBS exclusion is accomplishing its purported goals of encouraging more high-tech startup formation in the U.S. economy. One study in 2018 found that the exclusion increased funding slightly for qualifying businesses, but those that benefited the most were those which generally had high administrative capacity, meaning they were less likely to be “small.”8 This same study, and one from 2012, found that the early-stage investors—rather than the businesses themselves—captured about a third of the benefit.9

Therefore, the extent to which qualifying businesses truly benefit from the QSBS exclusion is unclear. Most small businesses are precluded from using it while providing a windfall for high-tech startup founders, investors, and employees. These companies are already generally formed as C-corporations due to the administrative complexity of establishing companies as passthrough entities, the greater ease of C-corporations to attract investors, and the prevalence of investors—such as foreign investors and pension funds—who are indifferent to obtaining passthrough losses because they are either not taxed by the United States or are tax-exempt.10

In short, the QSBS exclusion provides a tax break to the founders, investors, and employees in early-stage startups who would have founded, invested, and worked anyway. The provision is giving away tax revenue without providing any meaningful incentive to future innovation and economic growth. Indeed, the QSBS tax exemption provides a massive tax break to taxpayers who arguably need it the least.

Tax data from the IRS show that tax returns using the QSBS exclusion between 2003 and 2020 had, on average, at least $500,000 of reported QSBS capital gains.11 Because neither these taxpayers’ income nor their wealth affect their eligibility to claim the QSBS exclusion, taxpayers with millions of dollars of income and assets pay the same rate — that is, zero—on their post-2010 QSBS capital gains as do taxpayers with minimal income and assets.

The QSBS exclusion also disproportionately benefits White taxpayers compared to Black and Latino taxpayers. As described earlier, the provision benefits startup founders, investors, and early employees—groups in which Black and Latino taxpayers are traditionally underrepresented. As reported by Crunchbase, more than 77 percent of VC-backed startup founders are White, while only 2.8 percent of founders are Black or Latino (the remainder are mostly Asian American founders.)12 Venture capitalist and tech-sector employment by gender and race and ethnicity reveals a similar lack of diversity, with White men managing 93 percent of all VC dollars and the overwhelming majority of tech-sector employees being either White or Asian men. 13

Taxpayers of color also generally obtain their income from working, as opposed to making investments that result in tax-preferred capital gains. This is especially true for investments in companies that are not publicly traded and are therefore inaccessible to lay investors. According to the Federal Reserve Board’s Survey of Consumer Finances, Black and Latino families have, on average, approximately 30 percent of the capital assets of privately held businesses of all kinds that White families own.14 Thus, Black and Latino taxpayers have less access to the investments that can result in qualified small business stock tax benefits.

The cost of the Qualified Small Business Stock exclusion

The U.S. Department of Treasury estimates that repealing the QSBS exclusion would result in $21.3 billion of additional tax revenue between 2023 and 2032, or about $2.1 billion per year.15 The cost of foregone revenue is difficult to measure since qualified small business stock owners might hold their qualified small business stock beyond the 10-year budget window, possibly even until death. This results in complete avoidance of capital gains taxes due to heirs receiving the shares at a stepped up basis, meaning that gain from any future sale is calculated using the value at the time of inheritance rather than the price that was paid by the original owner.

But the lost tax revenue is almost certainly higher than government estimates indicate. Publicly available IRS data only captures QSBS capital gains from stock acquired prior to 2010, which is excluded at a rate of 50 percent or 75 percent. The untaxed capital gains from qualified small business stock obtained after 2010 is fully excluded but is not reported in data provided by the IRS, despite strong evidence that post-2010 QSBS issuance is increasing.16 If post-2010 QSBS capital gains are simply equal to pre-2010 QSBS (still unrealized) gains, then tax revenue lost per year could triple to approximately $3 billion per year.17 (See Table 1.)

Table 1

But it is highly likely that the amount of qualified small business stock held by founders, investors, and early employees increased substantially after 2010. Data from recent Initial Public Offerings indicate that the true cost probably exceeds the estimates issued by government officials, potentially by an order of magnitude.18 Additionally, it has been widely reported that lawyers and accountants have devised sophisticated tax planning techniques to take advantage of the 2010 expansion of the benefit.19

Indeed, although the QSBS exclusion is limited to the greater of $10 million or ten times the basis of the taxpayer’s investment, qualified small business stock can be gifted to other taxpayers who are then able to claim their own $10 million (or greater) exemption.20 An investor anticipating that their stock holdings will someday become valuable can give their stock to friends and family, increasing the exemption many times over.

Holders giving qualified small business stock also are increasingly using alternative structures, such as trusts, to multiply the exemption amount. Because trusts can function as distinct taxable entities even if they have identical beneficiaries, tax advisors have suggested that giving qualified small business stock to qualifying trusts allows for essentially unlimited exclusions.21

This means an investor in a startup with $100 million of capital gains on their qualified small business stock need only create ten trusts all naming the investor’s children as beneficiaries to exclude all this profit from federal taxation. Because the IRS has yet to promulgate regulations clarifying the propriety of these tax planning techniques, savvy taxpayers are able to easily circumvent the stated exemption limits.

These significant costs might still be worth bearing if the QSBS exclusion truly motivated innovation and economic growth. There is no compelling evidence, however, that startup founders, investors, and early employees are engaging in these actions because of the tax savings. For instance, U.S. venture capital financing in 2021 was approximately $330 billion, according to the accounting and business advisory firm KPMG.22

If current government estimates of the cost of the QSBS exclusion are accurate, then it’s unlikely that savings for the exclusion’s beneficiaries of less than 1 percent of total capital allocated will move the needle with regards to early stage investments in startup firms. The QSBS exclusion is likely conferring a windfall on wealthy taxpayers to do what they would have done anyway.

Options for reforming the Qualified Small Business Stock exclusion

The simplest solution is for Congress to repeal the QSBS exclusion in its entirety. In the absence of total repeal, however, imposing additional ability-to-pay restrictions on its eligibility would result in less revenue losses to the U.S. Treasury Department and less inequitable capital gains tax breaks accruing to wealthy investors.

The income limitation and preclusion of eligibility for trusts and estates contained in the Build Back Better Act, for example, was a step in the right direction, but a more nuanced phaseout that increasingly reduced the exclusion as income for investors, founders, and early employees holding qualified small business stock would do more to correct the provision’s distributional inequities. For instance, each dollar of income above $400,000 could reduce the permitted exclusion by an identical amount, thereby precluding the exemption for taxpayers with incomes greater than $800,000.

The Internal Revenue Service should also promulgate regulations that curb abusive qualified small business stock tax and accounting transactions. For instance, current IRS guidance is silent on whether a company’s valuation can be calculated by reference to the adjusted tax basis of the company’s assets. If so, the bonus depreciation that new businesses are permitted to take can artificially decreases a startup company’s “aggregate gross assets” for purposes of the $50 million determination, thereby permitting businesses with valuations much higher than $50 million to still be classified as “small” for QSBS exclusion purposes.

Similarly, the IRS should administratively curtail the ability of savvy taxpayers to gift qualified small business stock to family members and use trusts, especially those with identical beneficiaries, to multiply the QSBS exclusion. Stock should lose its QSBS exclusion status upon its transfer, thereby preventing the original recipients of this now-valuable stock from shifting the tax benefits to other people. The stated purpose of the QSBS exclusion is to promote the development of small high-tech startup businesses, not to provide the friends and family of those investors with tax-free capital gains.

There is limited publicly available data on the QSBS exclusion. Policymakers, economists, and tax specialists alike know neither how much the exclusion really costs, nor the attributes of the taxpayers that qualify for it. Because QSBS exempt capital gains are stated on taxpayer returns, the IRS can and should release precise numbers on how much QSBS exempt capital gains are actually being excluded.

The IRS also should release data on the attributes of the taxpayers availing themselves of the QSBS exclusion. The extent to which the exclusion is used primarily by taxpayers that already have hundreds of thousands of dollars or much more in other income should inform future policy debates about the efficacy of the exemption in promoting small business formation, innovation, and economic growth.

States also have a role in reforming the QSBS exclusion. Of the more than 40 states that tax capital gains, only five include federally excluded QSBS capital gains into their capital gains tax base, and only two of them boast high-tech hotbeds, California and New Jersey.23 The other states unnecessarily piggyback off of federal definitions of capital gains to exclude qualified business stock gains at the state level. States should instead treat capital gains from qualified small business stock identically to other capital gains, and not throw away good state fiscal revenue just because the federal government does so.

Conclusion

The Qualified Small Business Stock exclusion provides an incentive for investment and economic behavior that likely would have happened anyway among the beneficiaries of this capital gains exclusion—early venture capital and angel investors in start-up firms, their founders, and their earlier employees—at a revenue cost that likely exceeds current governmental estimates. By excluding these capital gains, the provision gives an unneeded windfall to the wealthy.

The QSBS exclusion is most prevalent in the tech sector, an industry in which certain racial and ethnic groups have been systematically excluded. This makes its continued prevalence that much more indefensible. The IRS, the U.S. Congress, and state legislatures and state tax authorities should all strive to curtail its significance in the U.S. tax code and state tax codes.

— Manoj Viswanathan is a professor of law and the Harry and Lillian Hastings Research Chair and Co-Director of the Center on Tax law at the University of California College of the Law, San Francisco (formerly UC Hastings)

End Notes

1. Manoj Viswanathan, “The Qualified Small Business Stock Exclusion: How Startup Shareholders Get $10 Million (Or More) Tax-Free,” 120 Columbia Law Review Forum 38 (2020), available at https://columbialawreview.org/content/the-qualified-small-business-stock-exclusion-how-startup-shareholders-get-10-million-or-more-tax-free/.

2. 135 Cong. Rec. S10268-01, 135 Cong. Rec. S10268-01, S10280, 1989 WL 193789 (Aug. 4, 1989), available at https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/GPO-CRECB-1989-pt1.

3. 137 Cong. Rec. S16213-02, 137 Cong. Rec. S16213-02, S16219, 1991 WL 229544, 16 (Nov. 7, 1991), available at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1991-pt21/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1991-pt21-2-2.pdf.

4. IRC §1202(e)(3), available at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2011-title26/pdf/USCODE-2011-title26-subtitleA-chap1-subchapP-partI-sec1202.pdf.

5. Viswanathan, “The Qualified Small Business Stock Exclusion: How Startup Shareholders Get $10 Million (Or More) Tax-Free.”

6. U.S. Government Publishing Office, Public Law 111-240, “Small Business Jobs Act of 2010” (September 27, 2010), available at https://www.congress.gov/111/plaws/publ240/PLAW-111publ240.pdf.

7. Internal Revenue Code §1202(d)(2).

8. See Alexander Edwards and Maximilian Todtenhaupt, “Capital Gains Taxation and Funding for Start-Ups” (October 7, 2018), available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3265385 (finding that the QSBS exclusion increases funding for startups by 12 percent and that one-third of the benefit is captured by investors rather than the startups).

9. Other work has found that the exclusion is needlessly inefficient and distortionary. See Ibid, and also Alan D. Viard, “The Misdirected Debate and the Small Business Stock Exclusion,” Tax Notes (Feb. 6, 2012), available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2218388.

10. Greg Polsky, “Explaining Choice-of-Entity Decisions by Silicon Valley Start-Ups,” Hastings Law Journal 70 (410) (2019), available at https://hastingslawjournal.org/wp-content/uploads/70.2-Polsky-2.pdf.

11. IRS Statistics on Income, 2003-2020 (on file with the Washington Center for Equitable Growth). Publicly available IRS data only captures QSBS capital gains tax breaks from before 2010. Thus, this number likely understates the true amount of QSBS capital gains.

12. Mary Ann Azevedo, “Untapped Opportunity: Minority Founders Still Being Overlooked” (Feb. 27, 2019), available at https://news.crunchbase.com/venture/untapped-opportunity-minority-founders-still-being-overlooked/

13. Suraj Gupta, “Diversity: The Holy Grail of Venture Capitalism” (May 26, 2022), available at https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesbusinesscouncil/2022/05/26/diversity-the-holy-grail-of-venture-capital/?sh=330f7d374178; See also Sam Dean and Johana Bhuiyan, “Why are Black and Latino people still kept out of the tech industry?,” The Los Angeles Times (June 24, 2020), available at https://www.latimes.com/business/technology/story/2020-06-24/tech-started-publicly-taking-lack-of-diversity-seriously-in-2014-why-has-so-little-changed-for-black-workers.

14. Urban Institute, “Racial Disparities and the Income Tax System” (Jan. 30, 2020), available at https://apps.urban.org/features/race-and-taxes/#capital-gains-and-dividends.

15. U.S. Dept. of Treasury, Office of Tax Analysis, Tax Expenditures in Fiscal Year 2024, available at https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/131/Tax-Expenditures-FY2024-update.pdf. This analysis assumes no behavior changes if the tax provision is repealed.

16. Viswanathan, “The Qualified Small Business Stock Exclusion: How Startup Shareholders Get $10 Million (Or More) Tax-Free.

17. Ibid. Because pre-2010 QSBS capital gains are excluded at between 50 percent and 75 percent, and because post-2010 QSBS capital gains are excluded at 100 percent, each dollar of post-2010 QSBS capital gain results in up to twice as much lost tax revenue as each dollar of pre-2010 QSBS capital gain.

18. Ibid.

19. Jesse Drucker, “A Lavish Tax Dodge for the Ultrawealthy Is Easily Multiplied,” The New York Times (Dec. 28, 2021), available at https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/28/business/tax-break-qualified-small-business-stock.html; See also Alexander M. Stephenson, “Stacking the Chips,” 76 The Tax Lawyer 2 (2023), available at https://www.americanbar.org/digital-asset-abstract.html/content/dam/aba/publishing/tax_lawyer/vol76/762/5-stephenson-stackingthechips-ttl-23win-pp419-450.pdf.

20. Internal Revenue Code §1202(h).

21. See, for example, Frost, Brown, Todd Attorneys, “Maximizing the Section 1202 Gain Exclusion Amount,” (October 67, 2012), available at https://frostbrowntodd.com/maximizing-the-section-1202-gain-exclusion-amount/.

22. KPMG, “Global Venture Capital Annual Investment Shatters Records Following Another Healthy Quarter” (Jan. 19, 2022), available at https://kpmg.com/xx/en/home/media/press-releases/2022/01/global-venture-capital-annual-investment-shatters-records-following-another-healthy-quarter.html.

23. These states are comprised of Alabama, California, Mississippi, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania.