Overview

Across Europe, populist parties—once relegated to the political fringe—are now mainstays of national politics. Some are even winning power in the Netherlands, Sweden, Italy, Austria, and beyond. Whether left-wing or right-wing, populists share a message that resonates widely: The system has failed you, but we can take you back to something better.

What is it about this nostalgic promise that proves so powerful? In my recent research with Tyler Reny of Claremont Graduate University and Jeremy Ferwerda of Dartmouth College,1 we seek answers to exactly that question, surveying nearly 20,000 people across 19 European countries.2 We find that many of these voters support populist parties not just because of economic anxiety or ideological conviction, but also because they believe that people like them had it better in the past. This phenomenon—what we call nostalgic deprivation—captures a potent psychological undercurrent shaping European politics today.

This sentiment is not simply personal nostalgia for a golden youth. It also is the belief that one’s broader social group—defined by class, culture, geography, or political identity—has declined in wealth, respect, or influence over the past generation.3 In Hungary, Italy, Slovenia, and even parts of Western Europe, large portions of the public feel not only left behind but left out as well.

Consider the case of France, where Marine Le Pen’s right-wing populist party, National Rally, steadily increased its vote share over the past decade. Her messaging emphasized a return to traditional French values, national sovereignty, and protection from globalization. This appeal resonates strongly with voters in deindustrialized regions who feel abandoned by Paris-based elites. Similarly, in Germany, the Alternative for Germany, or AfD populist party has capitalized on eastern Germans’ sense of marginalization in the post-reunification era, painting a picture of cultural erosion and political neglect.

It is striking that this sense of loss doesn’t always align with objective reality. Certainly, many fringe party supporters experience measurable economic disadvantages.4 Yet social scientists have shown that voters’ subjective attitudes similarly predict their political preferences.5

In my own aforementioned research, we find that many people who report feeling worse-off politically or socially today are not necessarily facing personal hardship. And in countries where living standards have improved dramatically since the fall of communism, such as Poland or Slovakia, we find that nostalgic deprivation remains common. The perception—not necessarily the data or reality—is what drives political behavior.6

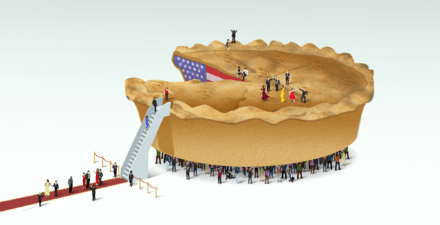

This helps explain the cross-cutting appeal of populism in Europe, but also in the United States under President Donald Trump. Left-wing populist parties emphasize economic injustice, while right-wing populists focus on cultural and national identity. But both speak to voters who feel that “people like me” were once more central to society—and are now dismissed by political elites.

This essay first delves into our research on nostalgic deprivation and its root causes before projecting future trends in populist support at the national level. We then turn to the implications of this political and psychological dynamic on the prospects for mainstream parties going forward.

Strong feelings of status loss drive populism’s rise

In our research, my co-authors and I find that these emotions of being left behind or worse off than they used to be are not just common, but politically potent, too. Across countries in Europe, those who feel deprived compared to the past—economically, socially, or politically—are significantly more likely to support populist parties.

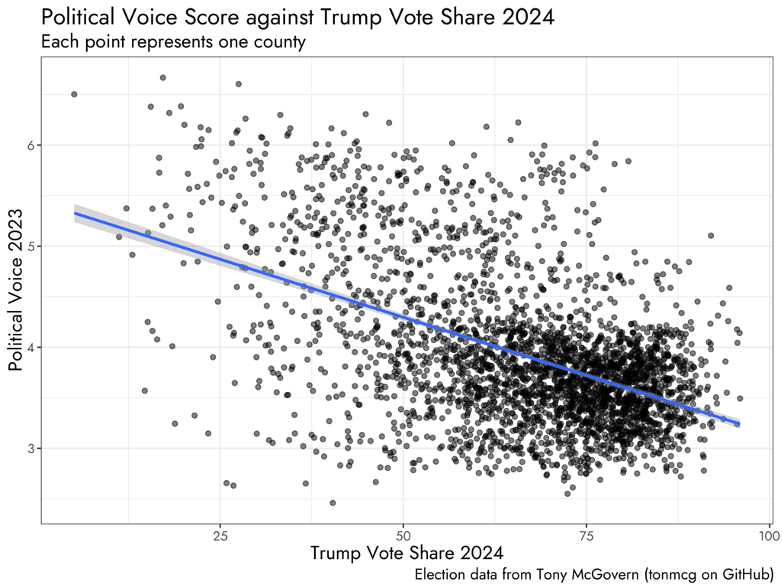

We measure this sentiment by inquiring about respondents’ scaled sense of financial well-being, political power, and social status today and 25 years ago. This allows us to more precisely observe feelings of loss without querying people about it directly. Importantly, we find that these feelings vary by ideological camp: Voters on the right are more likely to feel politically deprived, believing that their group has lost voice or representation, while those on the left expressed more social deprivation—feeling less respected or valued in society.

In short, populist energy is not fueled by a single grievance. Rather, it is a shared feeling of collective decline, refracted through different lenses.

Take Spain’s left-wing populist Podemos party, which rose in prominence in response to the 2008 global financial crisis. Its leaders channeled the anger of a generation, those who felt not just economically stunted but also ignored in the corridors of power. These voters demanded redistribution of resources and restoration of dignity. At the same time, Spain’s far-right party, Vox, appealed to a very different kind of nostalgia—for a unified, Catholic Spain that many feel is disappearing amid secularization, regional devolution, and immigration. These diametrically opposed visions share a common root: a perceived loss of standing among certain voters.

Somewhat paradoxically, our research also reveals that nostalgic deprivation is most impactful where populist parties are not in power. In these countries, populists can make sweeping promises to restore what was lost. But once they hold office, their ability to fulfill these promises is constrained. Subsequently, their supporters, faced with present-day responsibilities rather than a symbolic mission of revival, tend to report less deprivation—and, sometimes, less enthusiasm.

Hungary offers a partial exception. Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has managed to retain a populist appeal despite being in power for more than a decade. He does this by continuously identifying new external enemies—EU bureaucrats in Brussels, George Soros, immigrants—and presenting himself as a defender of Hungary’s authentic identity. Yet even in Hungary, some signs suggest that the emotional force of nostalgic deprivation is gradually waning, as allegations of corruption accumulate and the image of Prime Minister Orbán transitions from insurgent to establishment.

This, however, does not mean populist movements will fade once in office. If anything, it shows how resilient and adaptable they are. As long as voters continue to feel overlooked or disrespected, there will be a market for political actors who promise recognition.

Nostalgic deprivation is widespread across European nations

Our research finds that a sense of lost wealth or economic stability is most prominent in EU countries with the highest overall reported levels of nostalgic deprivation. By contrast, among those countries with lower overall reported deprivation, we find that perceived loss of social status is more conspicuous. The sense of lost political power is, on average, the least common form of deprivation expressed.

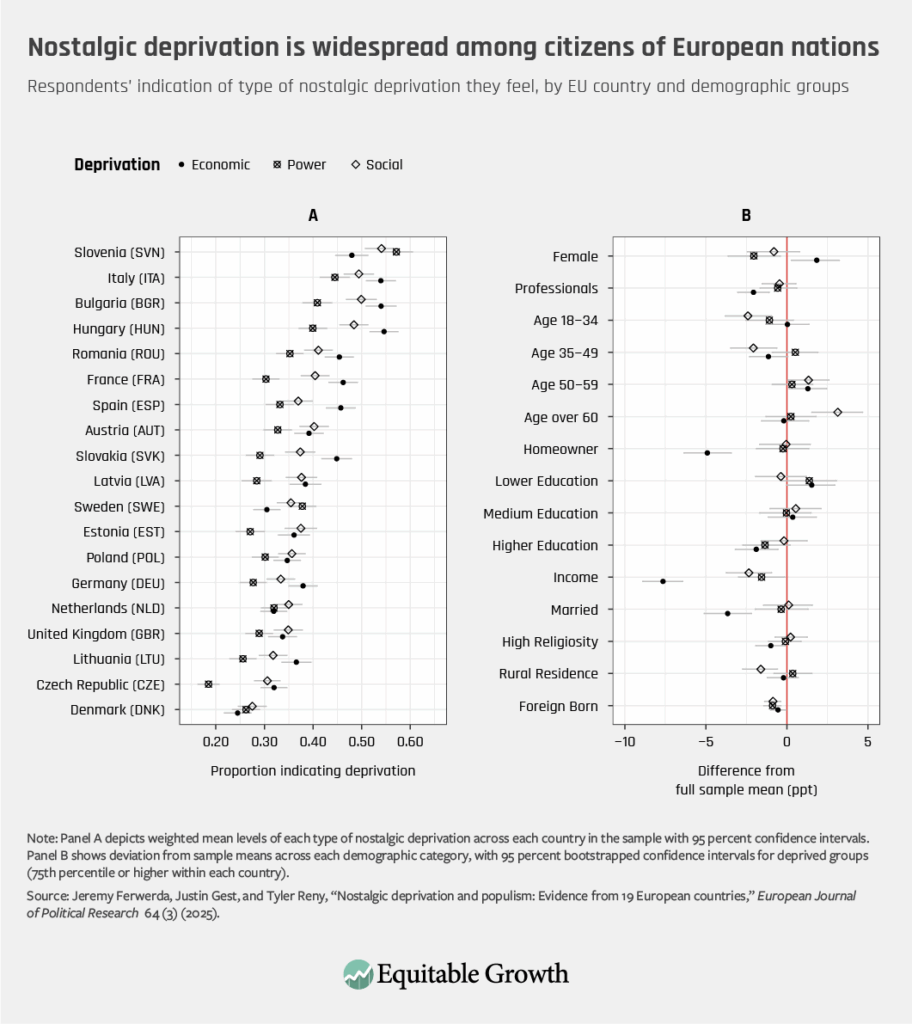

Figure 1 below shows that a sense of nostalgic deprivation—be it economic, political, or social—is widespread among European citizens. Panel A plots the proportion of respondents expressing economic, political power, and social deprivation in each country studied, with each dimension of deprivation rescaled between 0 and 1. Panel B examines the demographic characteristics of those respondents reporting the highest levels of each type of deprivation (75th percentile or higher within each country). Each point in Panel B indicates how the demographic characteristics of economically, politically, or socially deprived individuals, respectively, deviate from the full sample of respondents. Values to the right of the red line indicate cases where a group experienced more deprivation than all survey respondents as a whole within countries, while values to the left of the red line indicate cases where a group experienced less deprivation. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

As Panel A shows, the lowest rates of nostalgic deprivation are found in Denmark, where approximately a quarter of respondents indicated of deprivation to some extent, while the highest is in Slovenia, where roughly half of respondents do. Notably, the countries exhibiting the highest overall levels of deprivation—Slovenia, Italy, Hungary, and Bulgaria—were governed by populists during the survey fielding period. A clear exception to this pattern is Poland, which was governed by the right-wing populist Law and Justice party at the time of fielding our survey but displayed deprivation scores more consistent with its Baltic neighbors not governed by populist parties.

Still, when we aggregate the measure of deprivation, we find that respondents moving from the minimum to the maximum level of nostalgic deprivation would be 55 percentage points more likely to express populist attitudes in Western Europe and 29 percentage points more likely to do so in Eastern Europe. With respect to voting, the difference between locations is even sharper: We estimate that those citizens moving from the minimum to the maximum on the deprivation score would be 57 percentage points more likely to vote for a populist party in Western Europe and 17 percentage points more likely to support a populist party in Eastern Europe. The weaker results in Eastern Europe for this measure likely reflect that many populist parties in this region were incumbents at the time the survey was fielded.

Demographically, we find that those perceiving lost political clout are more likely to be men, while those perceiving lost economic stability are more likely to be women. We also see that socioeconomic indicators, such as people’s jobs, homeownership rates, education levels, and incomes are strongly correlated with economic deprivation and, to a lesser extent, with social deprivation. Perceived lost social status is notably correlated with age, with older respondents indicating elevated rates, and negatively correlated with living in a rural environment.

Despite these findings, however, the broader correlation between nostalgic deprivation and demographic characteristics remains relatively weak. In other words, on average, citizens who express high levels of deprivation are demographically similar to citizens who do not view their situation as pessimistically. High levels of nostalgic deprivation are evident in Western Europe, but also in Eastern Europe, where living conditions have improved more substantially over the past 25 years.

Potential for future support for populist parties

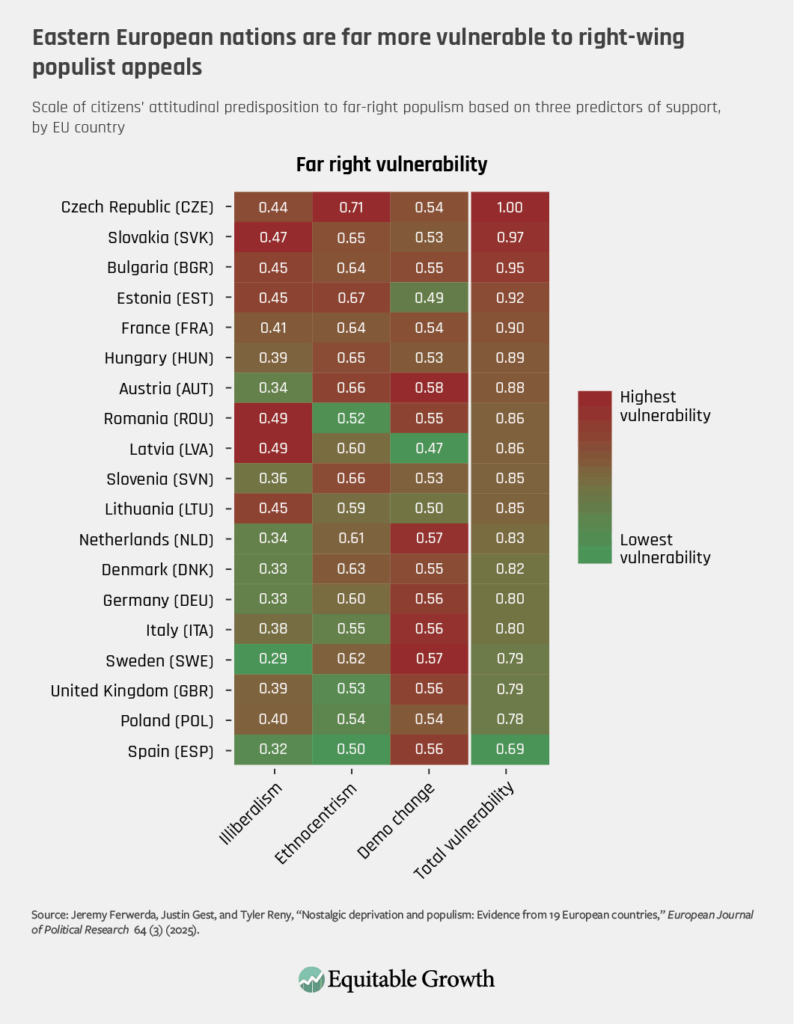

Which countries are most susceptible to far-right appeals in the future? Table 1 below lays out each country’s average score on the three separate attitudinal predispositions that, according to my research, are correlated to nostalgic deprivation and best predict far-right support: illiberal attitudes, or opposition to democratic principles; ethnocentrism, or the tendency to view one’s own culture as superior to others; and perceptions of demographic change, such as that caused by immigration.7 I add these scores together into a scale of far-right “vulnerability” (rescaled so that the highest vulnerability score is 1.00) to estimate how fertile each country’s public attitudes are toward far-right rhetoric and ideas.8

As Table 1 shows, we find much higher vulnerability to the far-right in Eastern Europe and much less in Western Europe, with the notable exceptions of Austria and France. (See Table 1.)

Table 1

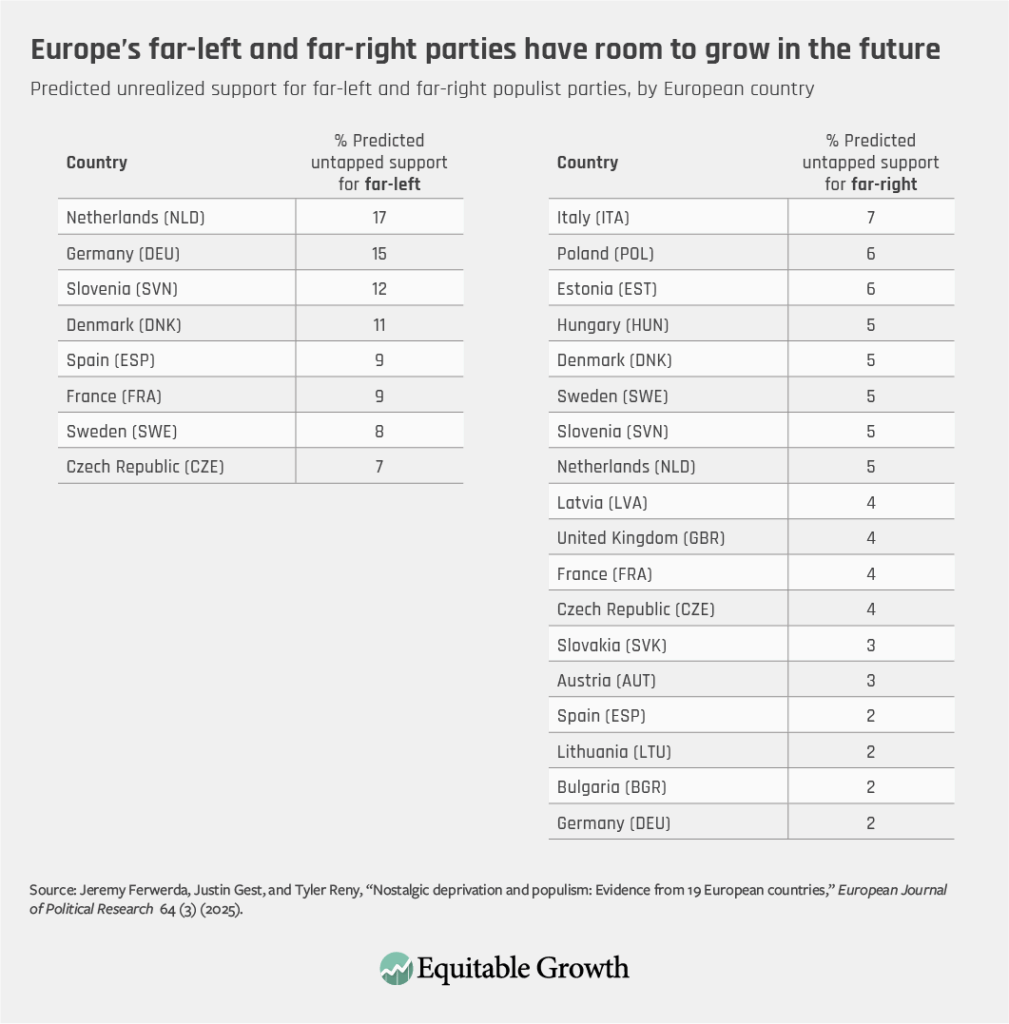

To identify the unrealized potential of far-right and far-left parties in different EU countries, my colleagues and I created a model that uses demographic and attitudinal data to predict which current mainstream center-left and center-right party supporters would be most likely to defect to the fringe in the future. We examine the average demographic and attitudinal characteristics of far-left and far-right supporters, as well as those of current center-left and center-right supporters who our model predicts would support the far-left or far-right down the road.

Looking at the far-right, there remains a substantial share of the population—about 4 percent of our sample—who do not currently support the far-right but are more ethnocentric, ideologically conservative, authoritarian, and illiberal than current far-right supporters. With the far-left, we also find that there is a substantial share of people—about 10 percent of our sample—who are young, single, low-income, and are relatively illiberal, and who could be persuaded to back the far-left in the future.

As such, there is modest potential for growth in support for the far-right, and potentially even more growth for the far left, across most of Europe. These findings suggest that Europe’s fringe parties have not yet peaked and still have room to grow. (See Table 2.)

Table 2

A dilemma for mainstream political parties

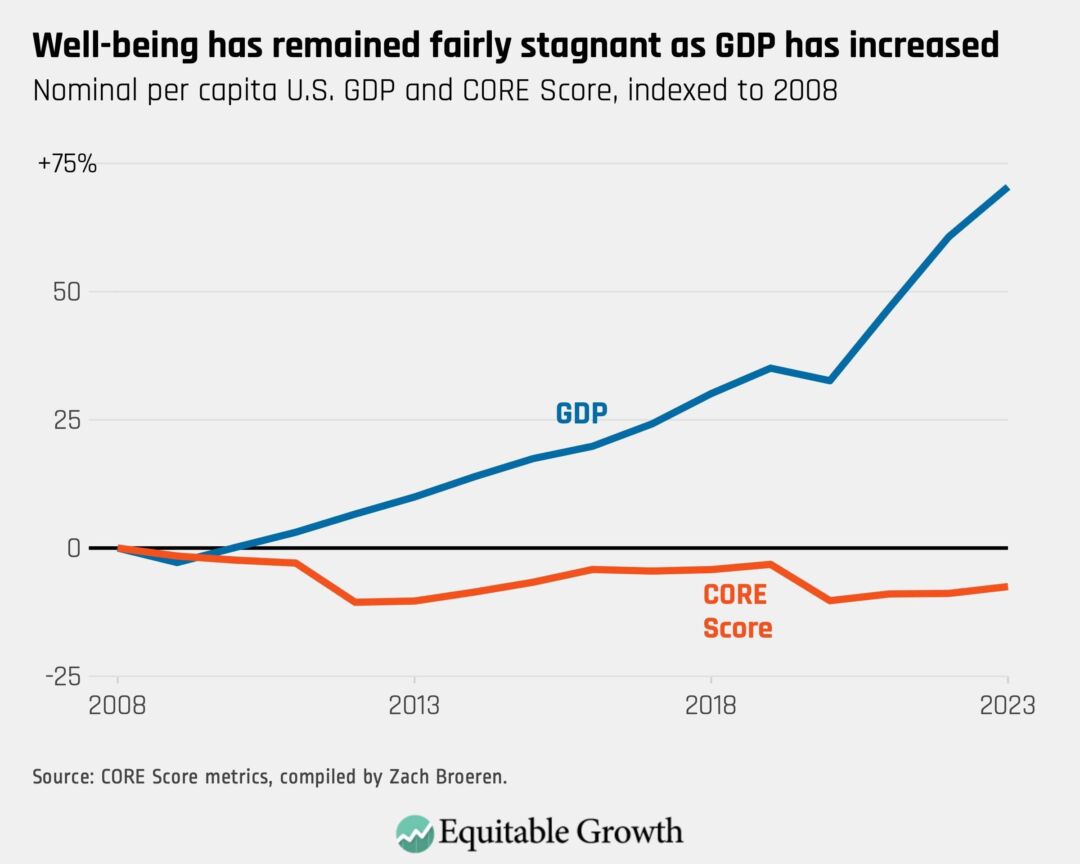

For mainstream political parties, the power of subjective feelings associated with fear, loss, and exclusion—feelings that are often separate from the empirical realities of the voters who express these emotions—creates a dilemma. Technocratic solutions, policy proposals, and Gross Domestic Product growth alone will not restore trust among these voters for the “establishment.”

Instead, what is needed is a reengagement with the emotional fabric of democratic life—an understanding that people vote not just with their wallets or ideologies, but also with their sense of belonging. That task is harder than it sounds.

But even though recognition cannot be legislated, it can be modeled through inclusive rhetoric, genuine consultation, and policies that reflect more than just economic efficiency. Political elites must find ways to speak to the diverse sources of dignity and identity that citizens hold dear to reassure these voters about their place in an uncertain future. This means attending not just to material needs but also to symbolic ones: the desire to be seen, heard, and respected.

Center-right and center-left governments would do well to design and effectively communicate policies that seek to rein in globalization’s excesses without diminishing the benefits of connected open markets. They should manage the flows of migration with selective, strategic admissions systems that identify newcomers best positioned to contribute to national goals.

Ultimately, though, these policies must also be laden with meaning. They must recognize that identity, history, and belonging are not just cultural touchstones—they are political forces as well. A politics of recognition does not mean pandering to prejudice. It means acknowledging the ways that people define themselves and making sure that diverse identities can find affirmation within a shared democratic project and shared national goals.

In this sense, nostalgic deprivation is not just a warning sign. It also is an opportunity to reflect on how democratic systems can better include those who feel excluded so as to create a future that people feel is truly theirs—rather than something they simply endure.

Conclusion

Europe’s experience with populism holds lessons for the United States, where similar trends are evident. Nostalgic slogans, polarized media, and a growing divide between urban and rural identities all contribute to a familiar feeling: the sense that “my” group once mattered more and now matters less.

In the United States, President Donald Trump’s “Make America Great Again” movement explicitly invoked this narrative.9 Because the MAGA movement needed to navigate the U.S. two-party system, its populism is awkwardly married with the Republican Party’s religious conservativism and aversion to taxing wealth. But ultimately, Trumpism is essentially about restoring lost political, economic, and cultural status10—even though, as in Europe, the appeal of this message does not always correlate with objective deprivation.

Populist voting is ultimately a reflexive response to rapid societal change. And both in the United States and in Europe, the past two generations have experienced rapidly increasing ethnic and religious diversity,11 which has eroded the position of formerly dominant demographic groups, leading to fears of reduced social status—or, at the extreme, “replacement” by immigrant populations. Concurrently, the consolidation of corporate power and deunionization in Europe and the United States has produced widening economic inequality, greater economic insecurity, and diminished prospects for socioeconomic mobility.12

Grievances associated with these cultural and economic transformations are commonly connected to growing support for far-right and far-left political movements, respectively. Yet both sets of grievances are linked to globalization—the expansion and intensifying interconnectedness of human migration and markets. The research my co-authors and I have done shows that while right- and left-wing populist platforms may ultimately reach different targets and point to different scapegoats, they appeal to voters with similar feelings about their own place in society and the economy.

Understanding these emotions isn’t an endorsement of its political outcomes. But ignoring them is perilous. Democracies depend not only on participation, but also on a shared belief in a system that sees and values everyone. When that belief erodes, the ground becomes fertile for those who claim they can restore what was lost—even if they cannot.

About the authors

Justin Gest is a professor of policy and government at George Mason University. He previously was a postdoctoral fellow and lecturer in Harvard University’s Departments of Government and Sociology. Gest earned his bachelor’s degree in government at Harvard University and his Ph.D. in government from the London School of Economics.

Did you find this content informative and engaging?

Get updates and stay in tune with U.S. economic inequality and growth!

Stay updated on our latest research