Lessons from new research on the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

Overview

Policymakers are increasingly paying attention to administrative burdens—those “frictions that people face in their encounters with public services.”1 In 2022, the Biden-Harris administration’s Office of Management and Budget launched an ambitious new effort, calling on federal agencies to better characterize and reduce administrative burdens present in public benefit programs as part of the administration’s commitment to advancing racial equity and improving customers’ experiences.2

Yet while some aspects of administrative burdens are relatively easier to measure and compare across members of the public and within different programs—for instance, the time it takes for individuals to complete the necessary paperwork—other measures of administrative burdens have proven harder to adopt and scale across agencies. In particular, federal agencies have been slow to consider and report on the psychological burdens that may be present for individuals when accessing public benefit programs.

This report contributes to the quantitative measurement of psychological burdens by examining a case study of a single social program: the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, which is administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. In this paper, I consider new quantitative measures of the psychological burdens faced by SNAP applicants, considering two aspects of psychological burdens: stress and stigma.

Using original surveys of SNAP applicants, I compare these new measures to recent work by public administration scholars on other proposed tools to quantify psychological burdens. I show that applicants have meaningful views about the stress they have experienced while applying for the program and the respect or stigma stemming from their interactions with program staff. I also show that stress and respect tap into distinct underlying concepts among SNAP applicants and require different strategies for measurement. That is, if scholars are interested in measuring respect, then they cannot simply extrapolate from measures of stress survey items and vice versa.

I then explore the distribution of these psychological burdens across the population of SNAP applicants, showing they are distributed unequally across race, ethnicity, age, and disability status. I find that Hispanic applicants and applicants with disabilities were substantially more likely to report experiencing stress than other demographic groups. I also find that Asian American and Native American applicants report the highest levels of stigma, compared to White applicants, and that individuals with disabilities, parents, and older applicants reported the highest levels of respect. Overall, older Americans stand out as reporting the lowest levels of stress and stigma compared to other applicants, potentially reflecting streamlined eligibility and outreach to this demographic group by, for example, SNAP program administrators and community-based organizations.

I also examine the relationship between time costs and psychological burdens, looking at how long applicants estimated it took them to complete their SNAP applications. I find that the relationship between time costs and stress was strongest for Black applicants and applicants with disabilities.

This analysis of the distribution of stress and stigma across SNAP applicants sheds light on the groups bearing the largest psychological costs when interacting with this particular income support program so that policymakers and program administrators can better target interventions to reduce these burdens. In so doing, the paper helps to illuminate the ways in which administrative burdens and their unequal distribution can reinforce existing social and economic disparities.

Aside from the findings about the distribution of psychological burdens across SNAP applicant subgroups, the design of the survey—and in particular the individual measures of stress and stigma—provide a model for further quantitative measures and analysis of psychological burdens. Federal agencies, including the Office of Management and Budget and the U.S. Department of Agriculture, could use this model to meet the aims of the federal government’s new initiative to reduce administrative burdens and better measure and identify all sources of burdens across benefit programs.

I conclude this report with policy recommendations for federal agencies to advance the burden-reduction initiative, in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program and more generally across executive branch agencies.

Defining administrative burdens and measuring their impacts: The need for more work on psychological burdens

Scholars are increasingly documenting the importance of administrative burdens—the “frictions that people face in their encounters with public services,” as described by Georgetown University sociologist Pamela Herd and her co-authors—for income support programs.3 Research shows that these burdens, which include the costs of learning about a program, submitting application or recertification materials, interacting with program staff, and understanding how to use public benefits, can pose significant barriers to accessing social programs, undermine individuals’ economic security and well-being, and diminish individuals’ faith in public programs and government institutions.4

Building on this research, policymakers have, in turn, increasingly adopted the administrative-burdens framework, using these concepts to describe and reduce the barriers that individuals experience when accessing public benefits and services.5 Most notably, the federal government now explicitly talks about administrative burdens as part of the review process for federal paperwork and regulations. Additionally, in 2022, the Biden-Harris administration launched an ambitious new effort calling on federal agencies to better characterize and reduce administrative burdens in income support and other social infrastructure programs as part of the administration’s commitment to advancing racial equity and improving customer experience.6

While some aspects of administrative burdens are relatively easier to measure and compare across members of the public and different programs—for instance, the time it takes for individuals to complete necessary paperwork—other measures of administrative burdens are harder to adopt and scale across agencies.7 In particular, federal agencies have been slow to consider and report on the psychological burdens that may be present for individuals when accessing income support programs.

These burdens may include, for instance, the disrespect or stigma individuals feel when needing to recount past traumas or intimate information to government agencies; the stress from uncertainty about how long one might need to wait before receiving benefits; or the anxiety associated with needing to compile multiple pieces of onerous documentation.

The 2022 burden-reduction initiative called on agencies to assess the presence and distribution of psychological burdens more comprehensively during benefit application or recertification.8 But executive branch agencies have been slower to formally document these burdens when proposing or revising forms or in the impact analyses of regulations potentially affecting access to public benefit programs. Those at the Office of Management and Budget who are leading the burden-reduction initiative have indicated in public remarks that a key barrier to agencies considering psychological burdens is that there are no straightforward quantitative measures that can easily characterize these burdens across programs and agencies.

By comparison, agencies have long been accustomed to using so-called burden hours—a measurement of how long it takes to fill out necessary paperwork—to measure the time costs associated with applying for or accessing income support programs. While burden hours often undercount the full extent of learning and compliance costs, they do offer an intuitive measure that is easy to grasp and understand, that provides clear comparisons across forms, programs, and agencies, and that has straightforward strategies for measurement through surveys, focus groups, and user observations.

With these challenges to the adoption of measuring psychological burdens in mind, this report explores whether it is possible to create quantitative measures of psychological burdens and then to use those indicators to yield insights about the distribution and sources of these burdens within a public benefit program. Building on other recent work in this area—in particular, I compare my measures to those proposed by Sebastian Jilke and co-authors in their 2024 paper, “Short and Sweet: Measuring Experiences of Administrative Burden”—I tap into both similar and different concepts, especially around dignity and respect.9

This report focuses on the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, an income support program administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture that offers low-income families benefits to supplement their food budgets. Reaching around 40 million U.S. individuals—and even more during economic downturns, when the program expands with increased demand—the program is the most important anti-hunger program in the U.S. welfare state and a critical economic stabilizer in recessions.10 Given its substantive importance and the fact that it has been studied before in the context of administrative burdens, this program offers an important case study for the measurement of psychological burdens.

Psychological burdens in the SNAP application process and their disparate impacts

The Office of Management and Budget’s 2022 guidance to federal agencies on reducing burdens references the need to better estimate and address different forms of burdens, including learning costs, compliance costs, and psychological costs. Psychological costs can include “the cognitive load, discomfort, stress, or anxiety a respondent may experience as a result of attempting to comply with a specific aspect of an information collection,” according to a 2022 OMB memo.11 While agencies have long estimated the time costs associated with completing a form, agencies have thus far not tended to include estimates of psychological burdens in information-collection requests.

This report draws on original research I conducted in January 2024, interviewing 1,492 individuals with experience applying for or receiving benefits from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, to try to quantify these psychological burdens.12 I specifically look at the stress applicants experienced while applying for and accessing the program and the respect or stigma they felt stemming from their interactions with program staff.

The survey provides an important window into the experiences of a diverse set of individuals with firsthand SNAP experiences. The survey population closely resembles the English-speaking population of SNAP beneficiaries in recent years along demographic characteristics, including race and ethnicity, age, education, employment status, and geographic region.

Let’s turn first to the survey results around stress.

Stress

To gauge the stress applicants felt around accessing SNAP benefits, I asked survey respondents the following question:

How much do you agree or disagree with the following statement: Applying for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), or food stamps, was stressful.

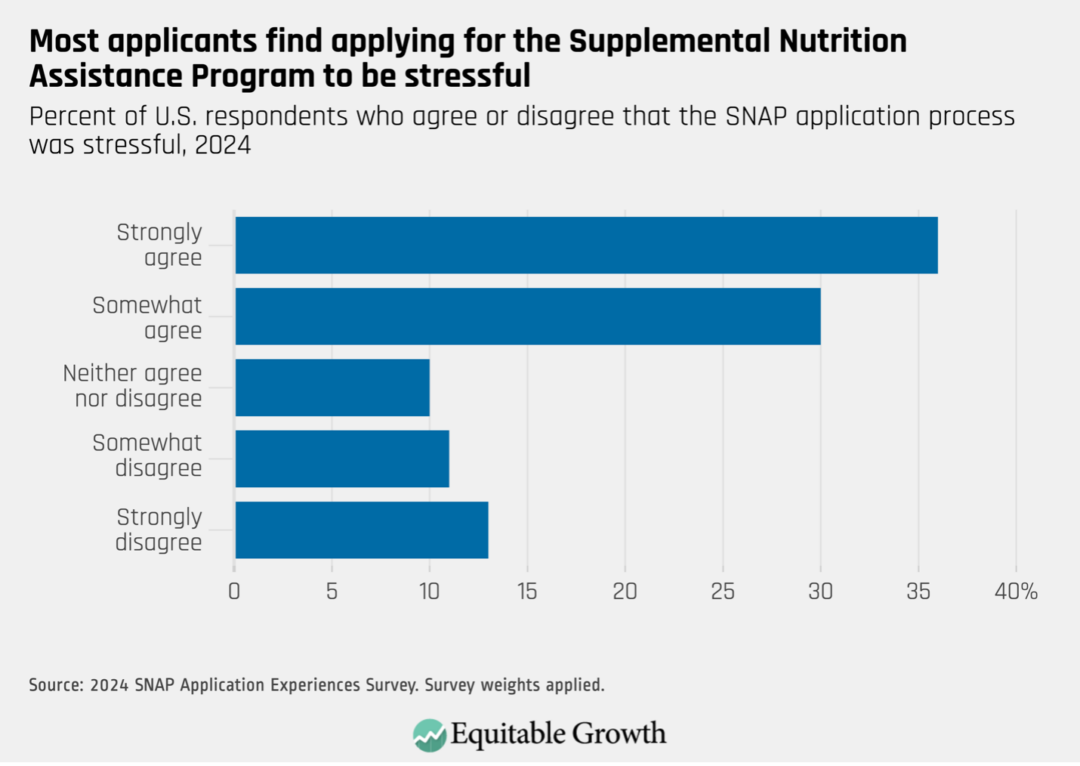

Respondents could provide six responses, ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree,” with an additional “not sure” option. Overall, two-thirds of respondents agreed that the application experience was stressful, including 36 percent of respondents who strongly agreed—the most common response. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

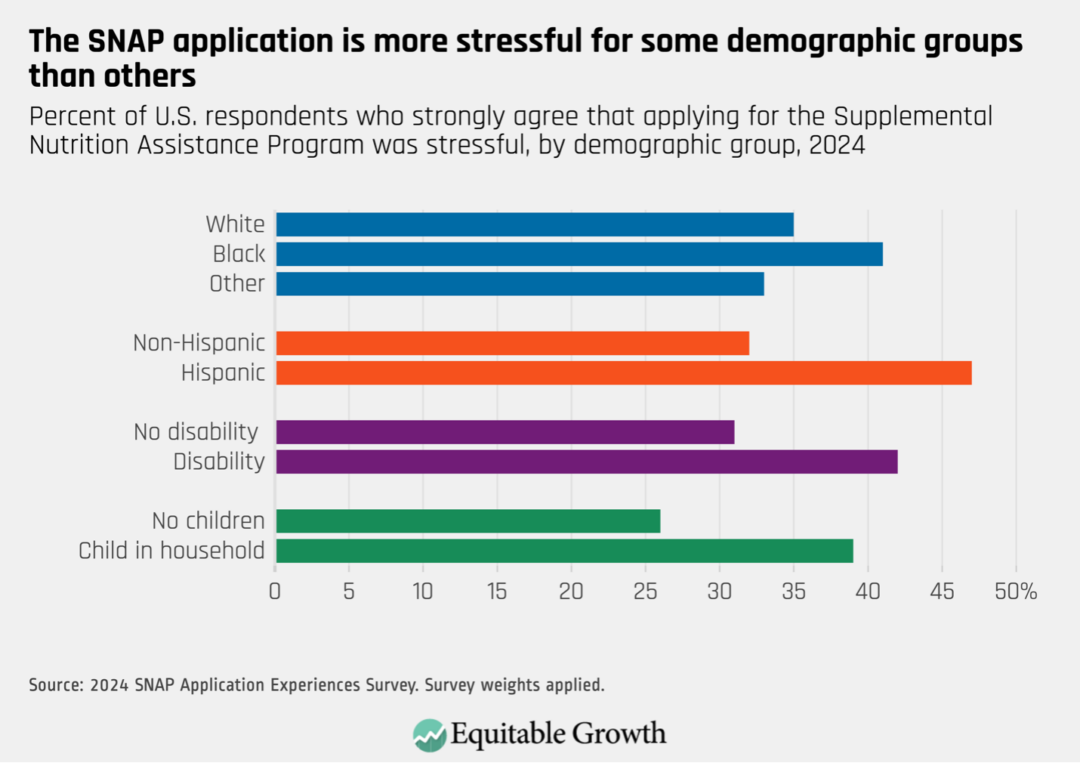

Not all respondents reported the same levels of stress, however, and I identified important differences across demographic groups. Black and Hispanic individuals in particular were more likely to strongly agree that the experience was stressful, as were individuals reporting a disability and parents of children. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

As Figure 2 shows, the largest stress gap was between parents and nonparents (a 51 percent gap), followed by the gap between Hispanic applicants and non-Hispanic applicants (a 45 percent gap) and the gap by disability status (a 37 percent gap). When accounting for these demographic characteristics together, the strongest predictors of stress included disability status and Hispanic ethnicity.13 The finding for Hispanic individuals reinforces other recent survey work by the Urban Institute documenting higher barriers to SNAP enrollment for Hispanic individuals.14

The survey also asked about the specific stressors that individuals encountered in the application process, including whether the respondents had trouble:

- Finding application materials

- Submitting application materials

- Understanding program rules and requirements

- Compiling necessary documents and records

- Contacting program staff in person

- Contacting program staff over the phone

- Visiting program offices

- Completing the forms

- Proving eligibility

- Getting benefits in a timely manner

- Documenting income

- Documenting assets

- Documenting medical expenses

- Documenting disability

- Documenting work hours

- Documenting utility expenses

Using this set of barriers, I examined which barriers were most predictive of a more stressful application experience.15 I find that the strongest predictor of more stressful experiences was reporting challenges communicating with SNAP administrative staff in person, and this was relatively consistent across different demographic groups.

The final dimension of stress that I explored involved the application assistance upon which individuals reported relying. I asked individuals about their application assistance in the following way:

Did you get any help applying for Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) or food stamps benefits from anyone? Please check all that apply.

Options included a friend or family member, a co-worker, an employer, a church or faith group, a union or worker group, a legal assistance or aid group, a food bank, a health care provider or clinic, government agency staff, a community group, or someone else.

I find three application assistance sources that had a statistically significant relationship with reported stress. Individuals who said they relied on help from family and friends, as well as food banks, tended to report higher levels of application stress. By comparison, individuals who said they relied on legal aid groups reported lower levels of application stress.

We cannot know from these data whether the application assistance itself is driving changes to stress levels or whether individuals with higher or lower levels of stress seek out particular forms of application assistance. This analysis does, however, help us pinpoint where individuals might be experiencing greater psychological burdens in the application process and thus allow policymakers to target application assistance and support accordingly.

Stigma

In addition to stress, I considered stigma, or what Harvard University’s Jessica Lasky-Fink and Elizabeth Linos at the University of California, Berkeley have described as “a social construct that can result in social rejection, devaluation, and discrimination based on a given attribute, identity, or behavior.”16 I focus on the stigma that SNAP applicants might experience in their interactions with program staff, using the following survey question:

How much do you agree or disagree with the following statement: Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), or food stamps, staff treated me with respect when I was applying for benefits.

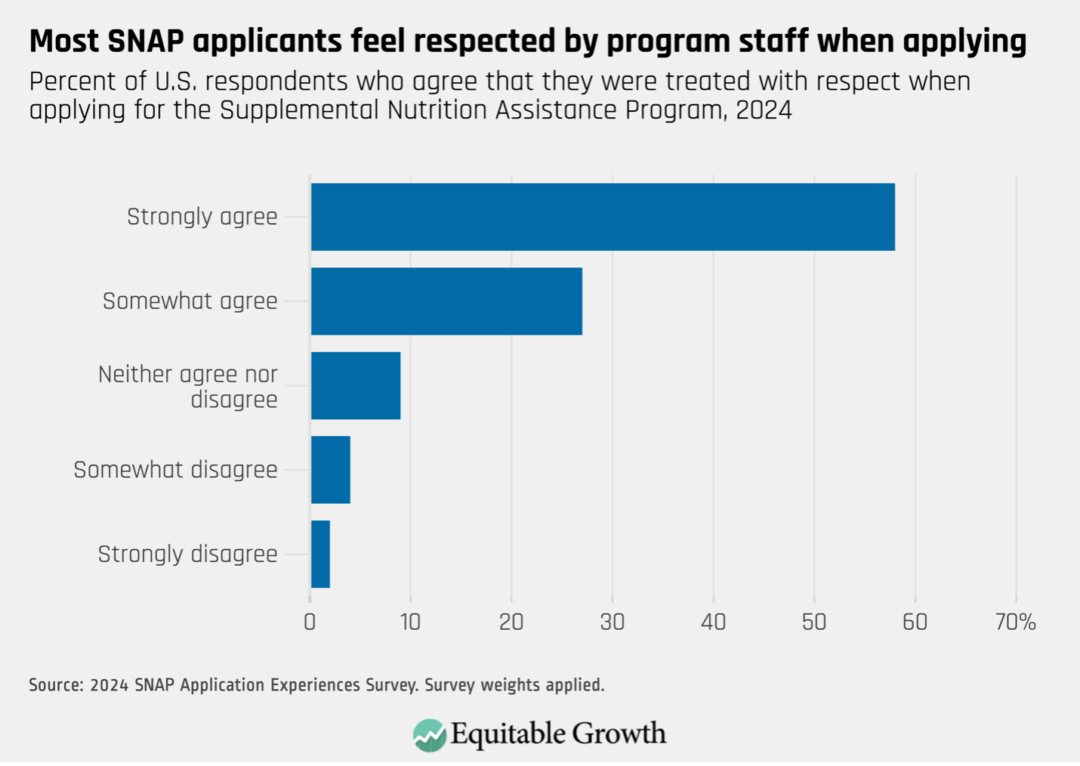

The vast majority of applicants reported high levels of respect (and therefore low levels of stigma) in their interactions with program staff. More than half of applicants—58 percent—strongly agreed with the statement, and another 27 percent somewhat agreed, totaling 85 percent of all applicants. Only 2 percent of applicants strongly disagreed, and just 4 percent somewhat disagreed. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

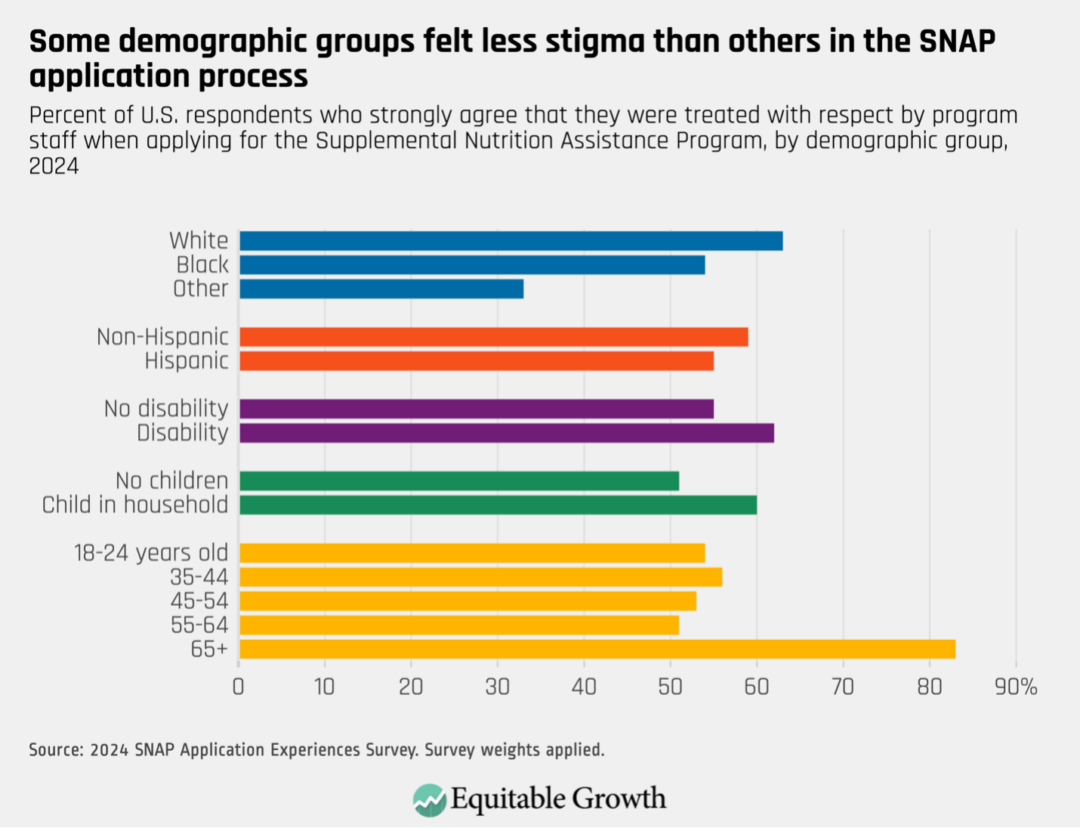

Nevertheless, as with the stress items, there were important differences across SNAP applicants with respect to the treatment they reported receiving from program staff. The largest differences were along race and age lines. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

As Figure 4 shows, non-White applicants were far less likely than White applicants to say that they had been treated with respect by program staff: 63 percent of White applicants strongly agreed, compared to 54 percent of Black applicants and 33 percent of other applications, which pools together Asian American or Pacific Islander applicants with American Indian/Native American and other races. Hispanic applicants were slightly less likely to say that they had been treated with respect than non-Hispanic applicants, but the differences were not large, compared to those by race.

In contrast to the stress results reported earlier, individuals reporting disabilities were more likely to say that they had been treated with respect than individuals who did not report disabilities. Similarly, parents reported higher levels of stress in the application process, but also reported higher levels of respect from program staff. I also find that older Americans were the group most likely to say that they had been treated with respect in the application process.

Learning costs in the SNAP application process and their relationship to psychological burdens

The 2022 burden-reduction guidance from the federal government also calls on agencies to better estimate individuals’ “beginning-to-end experience” with paperwork, including the time spent learning about program rules, as well as the time spent completing forms. Agencies to date have not typically included such expansive definitions of time costs in information collection requests, and so one objective of my survey was to understand a form of these time costs for SNAP applicants.

The survey included a question with the following prompt:

We’re interested in how long it took you to complete and submit your application for Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits, or food stamps. Use the slider below to indicate about how long it took for you to do the following things, even if it is just your best guess.

One of the aforementioned “things” was reading about the program and understandingrules—a category which captures part of the concept of learning costs. For this item, I restricted analysis to the 572 respondents who reported having applied for SNAP benefits in the past year to ensure that respondents were estimating time costs as accurately as possible.

On average, respondents reported that they spent 46 minutes reading about the program and understanding its rules. But this time estimate differed across demographic groups. Black respondents and respondents with children both reported spending more time on learning costs, with Black respondents reporting an average of 53 minutes (a 23 percent difference compared to White respondents) and parents reporting an average of 49 minutes (a 26 percent difference as compared to nonparents).17

Looking at the intersection between time spent on learning costs and stress, I find that there is no relationship in the aggregate. Individuals who reported more time spent learning program rules were not more likely to report stressful experiences, on average.

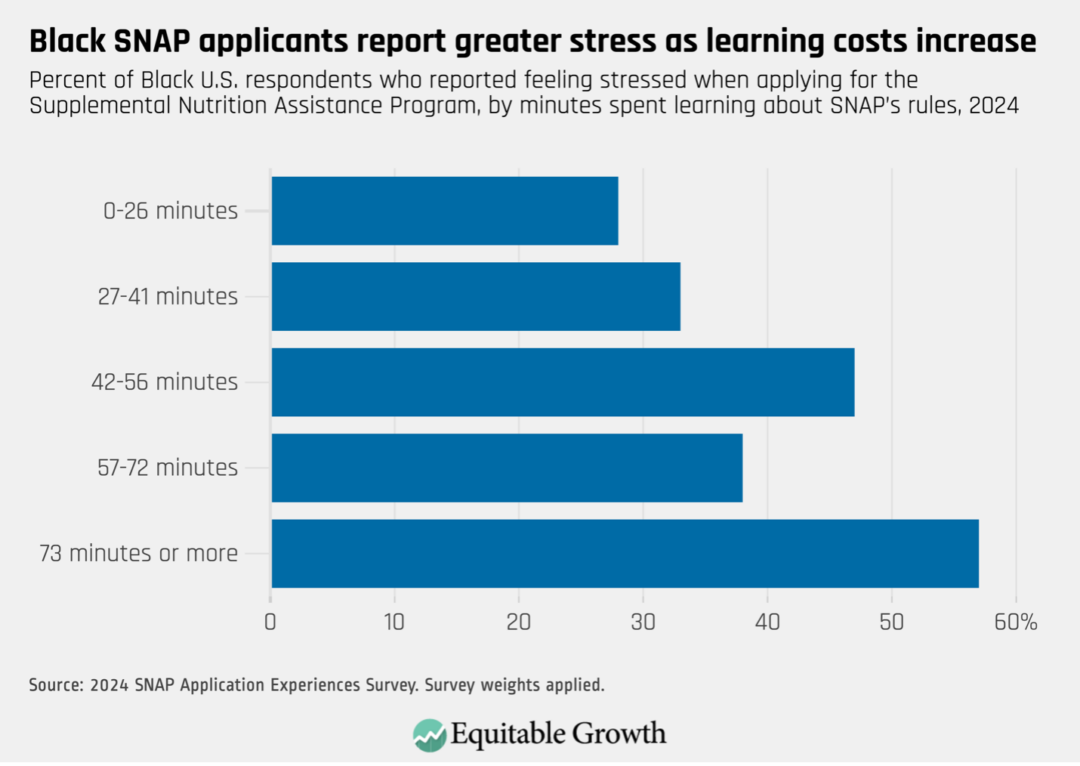

Yet this relationship was significantly different for Black individuals and individuals with disabilities. For both of these populations, greater time spent on learning costs was related to higher levels of stress, as Figure 5 shows for Black respondents. (See Figure 5.)

Figure 5

As Figure 5 demonstrates, among Black SNAP applicants who spent less than 27 minutes reading and learning about program rules, only 28 percent strongly agreed that the SNAP application experience was stressful. By comparison, nearly 60 percent of Black applicants who reported spending 73 minutes or more learning about SNAP application rules strongly agreed that the experience was stressful.

This suggests one important way that the effects of SNAP learning costs may be different for different demographic groups: While additional learning costs might not matter for the stress experienced by some groups, for others, it may increase stress or other psychological burdens.

Comparing measurements of psychological burdens

In addition to the primary survey, I also report results from a follow-up survey of 479 respondents that I fielded in March 2024 intended to compare my measures of psychological burdens with those of other scholars. In particular, I explored how my survey items about stress and respect compared to new work by Sebastian Jilke and his co-authors in their 2024 paper, “Short and Sweet: Measuring Experiences of Administrative Burden,” in which they propose a three-item battery of survey questions intended to measure psychological burdens:

- “How difficult was the process of finding information about the program, such as how to apply or what you needed to do to renew your benefit?”

- “How was the process of filling out the paperwork, providing proof of eligibility (such as pay stubs, proof of residence, birth certificates, etc.), and/or attending interviews?”

- “Please describe how you felt during these experiences: Frustrated?”18

I fielded these items, as well as my stress and respect items, in the March 2024 follow-up survey and examined how closely they were correlated with one another. Two important conclusions emerge from this analysis.

First, I find stress and respect (or stigma) are only modestly related to one another, indicating that they are tapping into different aspects of psychological burden, confirming my findings in the January 2024 survey. This affirms the need to distinguish between the two when measuring burdens in applications.

Second, and most importantly, I find that my measure of stress was strongly related to the Jilke scale, but the measures of respect were much less correlated with Jilke’s items. This suggests that to measure respect and dignity, agencies and researchers may need separate items, such as the ones I explore here, that are distinct from items related to stress, frustration, or learning costs.

Policy recommendations

My findings offer several areas in which the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Office of Management and Budget should consider revisions to SNAP application materials. There are also implications for the broader burden-reaction initiative that the Biden-Harris administration is spearheading across the federal government.

Encourage states to simplify SNAP application materials

Survey respondents consistently note the need for further simplification of application materials, including simplifying or eliminating burdensome documentation requirements and improving application design, including website design. Respondents point specifically to documentation requirements as a significant source of administrative burden.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture and Office of Management and Budget should work with state-level SNAP agencies to promote more streamlined application materials, including introducing mobile-friendly applications, encouraging greater use of categorical or “adjunctive eligibility” (that is, agencies using eligibility for one social benefit as proof of eligibility for another social benefit, or using an individual’s broad demographic category—e.g., pregnant person or person with a disability—as proof of eligibility for a social benefit) to reduce documentation requirements, eliminating unnecessary documentation records, and ensuring the availability of translated materials and culturally and linguistically sensitive application assistance.

Help states expand options for applicants to communicate with SNAP staff and reduce wait times

Survey respondents also consistently note the challenges they face communicating with SNAP program offices, both over the phone and in person. One of the strongest predictors of psychological stress in the application process involved challenges with in-person communications. Additionally, applicants consistently mentioned long phone wait times as an important barrier to receiving timely benefits.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Office of Management and Budget should work with state-level SNAP agencies to ensure that applicants have more options for communicating with program staff and that applicants receive information about the program and their applications as promptly as possible.

Ease access to application assistance and interventions for communities with higher levels of administrative burdens

My survey reveals important differences across demographic groups in administrative burdens, including psychological burdens related to stress. I find that Black and Hispanic applicants, applicants with disabilities, and applicants with children were all substantially more likely to report higher levels of stress in the SNAP application process than were other applicants, even net of other demographic characteristics.

This suggests that the U.S. Department of Agriculture, working together with state-level SNAP agencies, should target application assistance to these communities. In addition, the survey results indicate that individuals applying for the nutrition assistance program at food banks tend to experience higher levels of stress than other applicants, and so the federal government should ensure that food banks are equipped to support applicants requesting their assistance.

Develop and incorporate better measures of psychological burdens and beginning-to-end time costs

This survey suggests several ways that the U.S. Department of Agriculture and Office of Management and Budget could be assessing psychological burden, and especially stress and stigma. The federal government should support additional research on psychological burdens that could help inform further simplification of the SNAP application and improve service delivery, testing my survey’s measures and other approaches—and social scientists outside government could play an important role in contributing this research.

In addition, federal agencies should consider steps to estimate more accurately the full beginning-to-end time costs of applying for and recertifying SNAP benefits, including using survey-based measures, including those described in this report, as well as other approaches such as user testing or participant observation. The U.S. Department of Agriculture and Office of Management and Budget should pay particular attention to the ways that burdens may vary across different populations, as illustrated by the time costs and stress reported by Black SNAP applicants and SNAP applicants with disabilities in my survey. New measures of burden and time costs should be designed in ways sensitive to these differential impacts.

Engage and incorporate the lived experiences of SNAP applicants

Ongoing federal initiatives related to burden reduction and customer experience emphasize the need for more direct engagement with individuals who have lived experience with the programs the government administers. My survey illustrates one way that the federal agencies can draw from such experiences in a systematic manner: conducting interviews with a large sample of public benefit applicants.

The U.S. Department to Agriculture and Office of Management and Budget should explore more approaches to engage SNAP applicants that could inform improvements in the program and build greater trust with both applicants and beneficiaries. This outreach, however, should be mindful of the burden that engagement by applicants and beneficiaries with SNAP staff and processes can pose to underserved communities and should be conducted in a culturally and linguistically appropriate manner. The two agencies should consider strategies such as surveys, interviews, and partnerships with community-based organizations and networks of organizational affiliates that could provide sustainable platforms for such two-way, durable engagement.

Conclusion

Psychological burdens pose important barriers to individuals’ and families’ access to critical public benefits and services—and, through those effects, to their well-being. To tackle these burdens, U.S. federal agencies need better tools for measuring psychological burdens and their impacts on individuals.

Aside from the findings about the distribution of psychological burdens across SNAP applicant subgroups, the design of my survey—and in particular the individual measures of stress and stigma—provide a model for further quantitative measures and analysis of psychological burdens. Federal agencies, including the Office of Management and Budget and the U.S. Department of Agriculture, could use this model to meet the aims of the federal government’s new burden reduction initiative, to better measure and identify all sources of burdens across benefit programs.

Additionally, researchers, working together with individuals who have direct experience with relevant social programs, program administrators, and policymakers, can play an important role in building an evidence base for the sustained reduction of these burdens. This would not only improve the experience of individual applicants but also help policymakers target interventions for future applicants and beneficiaries of U.S. social infrastructure.

About the author

Alexander Hertel-Fernandez is a visiting fellow at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth and associate professor and vice dean at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs. He previously served as a political official in the U.S. Department of Labor and Office of Management and Budget.

Acknowledgements

For helpful feedback on this draft and related research, I thank the Equitable Growth communications team, Korin Davis, Donald Moynihan, Pamela Herd, Randy Akee, Chris Wimer, and Sophie Jacobson.

End Notes

1. Pamela Herd and others, “Administrative Burden as a Mechanism of Inequality in Policy Implementation,” RSF: Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 9 (5) (2023), available at https://www.rsfjournal.org/content/9/5/1

2. Office of Management and Budget, “Improving Access to Public Benefits Programs Through the Paperwork Reduction Act” (Executive Office of the President: M-22-10), p.1, available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/M-22-10.pdf; Office of Management and Budget, “Tackling the Time Tax: How the Federal Government Is Reducing Burdens to Accessing Critical Benefts and Services” (2023), available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/OIRA-2023-Burden-Reduction-Report.pdf.

3. Pamela Herd, Donaly Moynihan, and Amy Widman, “Identifying and Reducing Burdens in Administrative Processes” (2023).

4. For barriers, see Janet Currie, “The Take Up of Social Benefits.” Working Paper No. 10488 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2004), available at https://www.nber.org/papers/w10488; Wonsik Ko and Robert A. Moffitt, “Take-up of Social Benefits.” Working Paper No. 30148 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2022), available at https://www.nber.org/papers/w30148. For economic security and well-being, see Pamela Herd and Donald Moynihan, “How Administrative Burdens Can Harm Health,” Health Affairs Policy Brief (October 2 2020), available at https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20200904.405159/; Zachary Parolin, Christina J. Cross, and Rourke O’Brien, “Administrative Burdens and Economic Insecurity Among Black, Latino, and White Families,” RSF: Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 9 (5) (2023), available at https://www.rsfjournal.org/content/rsfjss/9/5/56.full.pdf. For faith in institutions, see Carolyn Barnes, State of Empowerment: Low-Income Families and the New Welfare State (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2020); Aske Halling and Martin Baekgaard, “Administrative Burden in Citizen-State Interactions: A Systematic Literature Review,” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 34 (2) (2024), available at https://academic.oup.com/jpart/article/34/2/180/7287903; Jamila Michener, Fragmented Democracy: Medicaid, Federalism, and Unequal Politics (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2018); Jamila Michener, Mallory SoRelle, and Chloe Thurston, “From the Margins to the Center: A Bottom-Up Approach to Welfare State Scholarship,” Perspectives on Politics 20 (1) (2020), available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/346793698_From_the_Margins_to_the_Center_A_Bottom-Up_Approach_to_Welfare_State_Scholarship.

5. Herd, Moynihan, and Widman, “Identifying and Reducing Burdens in Administrative Processes.”

6. Office of Management and Budget, “Improving Access to Public Benefits Programs Through the Paperwork Reduction Act”; Office of Management and Budget, “Strategies for Reducing Administrative Burden in Public Benefit and Service Programs” (Executive Office of the President, 2022) available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/BurdenReductionStrategies.pdf; Office of Management and Budget, “Tackling the Time Tax: How the Federal Government Is Reducing Burdens to Accessing Critical Benefts and Services.”

7. Herd, Moynihan, and Widman, “Identifying and Reducing Burdens in Administrative Processes,” pp. 47–8.

8. Office of Management and Budget, “Improving Access to Public Benefits Programs Through the Paperwork Reduction Act.”

9. Sebastian Jilke and others, “Short and sweet: Measuring experiences of administrative burden,” Journal of Behavioral Public Administration 7 (2024), available at https://pure.au.dk/portal/en/publications/short-and-sweet-measuring-experiences-of-administrative-burden; Marla McDaniel and others, “Customer Service Experiences and Enrollment Difficulties Vary Widely across Safety Net Programs” (Washington: Urban Institute, 2023), available at https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/2023-01/Customer%20Service%20Experiences%20and%20Enrollment%20Difficulties%20Vary%20Widely%20across%20Safety%20Net%20Programs.pdf.

10. Christopher J. Bosso, Why SNAP Works: A political history—and defense—of the food stamp program (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2023); Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “Policy Basics: The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)” (2022), available at https://www.cbpp.org/research/policy-basics-the-supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program-snap.

11. Office of Management and Budget, “Improving Access to Public Benefits Programs Through the Paperwork Reduction Act,” p.2.

12. See Appendix for more details on the survey.

13. Using an Ordinary Least Squares regression. Regression included survey weights.

14. McDaniel and others, “Customer Service Experiences and Enrollment Difficulties Vary Widely across Safety Net Programs.”

15. These questions were asked of individuals’ most recent application experience. Used Ordinary Least Squares, or OLS, regression analysis.

16. Jessica Lasky-Fink and Elizabeth Linos, “Improving Delivery of the Social Safety Net: The Role of Stigma,” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 34 (2) (2024), available at https://academic.oup.com/jpart/article-abstract/34/2/270/7280562?redirectedFrom=fulltext.

17. This difference continued to persist even when I accounted for other demographic characteristics in an OLS regression.

18. Jilke and others, “Short and sweet: Measuring experiences of administrative burden.”

Related

Explore the Equitable Growth network of experts around the country and get answers to today's most pressing questions!