Must-Read: One of the many, many reason to be very glad that I am here at Berkeley…

: David Card: “Peter J. Walker profiles David Card…

the economist who has questioned conventional wisdom on minimum wages, immigration, and education…

Must-Read: One of the many, many reason to be very glad that I am here at Berkeley…

: David Card: “Peter J. Walker profiles David Card…

the economist who has questioned conventional wisdom on minimum wages, immigration, and education…

Must-Watch: : Book Talk: “Concrete Economics” | Institute of Governmental Studies: “Friday, April 8, 2016 :: 4:00pm to 6:00pm :: 109 Moses Hall, IGS Library…

Must-Read: : A Bunch of Websites Migrate to Medium–Following: How We Live Online: “Medium has now placed its bets firmly on the ‘platform’ side of its bipolar business…

…It makes sense. Of the many reasons given for the decline of the media establishment, one of the most compelling has been the technological blind spot of many publishing companies, which operate at a slower pace than the portals and social networks that dictate how much traffic they receive. Part of the reason that BuzzFeed–to name the most prominent example–ate everyone else’s lunch so quickly is due to their substantial in-house tech department. Many others outsource development of new features to contractors. Medium wants to be everyone’s tech department (and, eventually, their ad department as well). In return for bearing the brunt of that work, Medium gets a bunch of publications to publish good stuff on their platform. And for a small website in particular, the pitch is good….

The dream of the internet, with its low overhead and near-infinite user base, is that a smart publication can find a large audience whose attention and traffic can sustain it. But it’s increasingly clear that the demands of the web economy are squeezing out the already-small middle class of independent content creators — even those with audiences in the hundreds of thousands. If Medium can help small and self-sustaining publishers like the Awl and Pacific Standard be better, for longer, that’s something to celebrate. But it also feels like the latest in a series of increasingly clear signals that the display-ad model, relying as it does on irritating and cheap programmatic ad networks, and competition with much larger publications (not to mention social networks), is not a sustainable business model even for the smart and popular.

Niall Ferguson (2013): An Open Letter to the Harvard Community: “Last week I said something stupid about John Maynard Keynes…

…Asked to comment on Keynes’ famous observation “In the long run we are all dead,” I suggested that Keynes was perhaps indifferent to the long run because he had no children, and that he had no children because he was gay. This was doubly stupid. First, it is obvious that people who do not have children also care about future generations. Second, I had forgotten that Keynes’ wife Lydia miscarried…

Niall, I think, misses the entire point. There is much, much more here than he recognizes… And what he recognizes is not, in fact, here at all…

Niall speaks of Keynes’s “In the long run we are all dead” as if it is a carpe diem argument–a “seize the day” argument, analogous to Marvell’s “To His Coy Mistress” or Herrick’s “To the Virgins”. Ferguson sees his task as that of explaining why Keynes adopted this be-a-grasshopper-not-an-ant “party like we’re gonna die young!” form of economics, or perhaps form of morality.

But that is not what is going on.

May 20, 2021

April 26, 2021

Go to Keynes’s Tract on Monetary Reform. Read pages 80-82, so you see the “in the long run we are all dead” quote in context. It is not part of any carpe diem argument. Two sentences earlier we find:

If, after the American Civil War, that American dollar had been stabilized and defined by law at 10 per cent below its present value, it would be safe to assume that n and p would now be just 10 per cent greater than they actually are and that the present values of k, r, and k’ would be entirely unaffected…

Six sentences earlier we find:

[T]he [Quantity] Theory [of Money] has often been expounded on the further assumption that a mere change in the quantity of the currency cannot affect k, r, and k’,–that is to say, in mathematical parlance, that n is an independent variable in relation to these quantities…

Two sentences later we find:

In actual experience, a change in n is liable to have a reaction both on k and k’ and on r…

And six sentences later we find:

There was a decided tendency on the part of these banks between 1900 and 1914 to bottle up gold when it flowed towards them and to part with it reluctantly when the tide was flowing the other way…

Keynes is discussing not how to “seize the day” for pleasure.

Keynes is discussing how to use the quantity theory of money as an analytical tool.

What he is saying is that you cannot assume that you can analyze the consequences of an altered time path of the quantity of cash in the economy–n, in Keynes’s notation–without considering whether the public’s demand for real cash balances k, the public’s demand for real checking-account balances k’, and banks’ desired reserves-to-deposits ratio r will also change. This is a principle that today’s economists call the “Lucas Critique”. (No, it is not clear to me why they do not call it the “Keynes Critique”.) And this critique is correct: assume that those three other variables are not themselves altered when you consider an altered path for the money stock is, as Keynes says in the sentence after “in the long run…”, for economists to set themselves too easy a task–it sweeps all the problems of analysis under the rug–and too useless a task–it generates predictions that are simply wrong.

In this extended discussion of how to use the quantity theory of money, the sentence “In the long run we are all dead” performs an important rhetorical role. It wakes up the reader, and gets him or her to reset an attention that may well be flagging. But it has nothing to do with attitudes toward the future, or with rates of time discount, or with a heedless pursuit of present pleasure.

So why do people think it does?

Note that we are speaking not just of Ferguson here, but of Mankiw and Hayek and Schumpeter and Himmelfarb and Peter Drucker and McCraw and even Heilbronner–along with many others.

I blame it on Hayek and Schumpeter. They appear to be the wellsprings.

Hayek is simply a bad actor–knowingly dishonest. In what Nicholas Wapshott delicately calls “misappropriation”, Hayek does not just quote “In the long run we are all dead” out of context but gives it a false context he makes up:

Are we not even told that, since ‘in the long run we are all dead’, policy should be guided entirely by short run considerations? I fear that these believers in the principle of apres nous le déluge may get what they have bargained for sooner than they wish.

And Hayek’s bad-faith writing yielded a lot of fruit: cf. Himmelfarb:

[S]omething of the “soul” of Bloomsbury penetrated even into Keynes’s economic theories. There is a discernible affinity between the Bloomsbury ethos, which put a premium on immediate and present satisfactions, and Keynesian economics, which is based entirely on the short run and precludes any long-term judgments. (Keynes’s famous remark. “In the long run we are all dead,” also has an obvious connection with his homosexuality – what Schumpeter delicately referred to as his “childless vision.”) The same ethos is reflected in the Keynesian doctrine that consumption rather than saving is the source of economic growth – indeed, that thrift is economically and socially harmful. In The Economic Consequences of the Peace, written long before The General Theory, Keynes ridiculed the “virtue” of saving. The capitalists, he said, deluded the working classes into thinking that their interests were best served by saving rather than consuming. This delusion was part of the age-old Puritan fallacy:

The duty of “saving” became nine-tenths of virtue and the growth of the cake the object of true religion. There grew round the non-consumption of the cake all those instincts of puritanism which in other ages has withdrawn itself from the world and has neglected the arts of production as well as those of enjoyment. And so the cake increased; but to what end was not clearly contemplated. Individuals would be exhorted not so much to abstain as to defer, and to cultivate the pleasures of security and anticipation. Saving was for old age or for your children; but this was only in theory – the virtue of the cake was that it was never to be consumed, neither by you nor by your children after you.

Never mind that Himmelfarb cuts off her quote from Keynes just before Keynes writes that he approves of this Puritan fallacy–that he is not, as Himmelfarb claims, ridiculing it, but rather praising it:

In the unconscious recesses of its being Society knew what it was about. The cake was really very small in proportion to the appetites of consumption, and no one, if it were shared all round, would be much the better off by the cutting of it. Society was working not for the small pleasures of today but for the future security and improvement of the race,—in fact for “progress.” If only the cake were not cut but was allowed to grow in the geometrical proportion predicted by Malthus of population, but not less true of compound interest, perhaps a day might come when there would at last be enough to go round, and when posterity could enter into the enjoyment of our labors…

So if you do read Himmelfarb, do so with great caution: this is a strange woman indeed[1].

As for Schumpeter, in Schumpeter’s Keynes obituary Schumpeter is working as hard as he can to try to minimize Keynes’s global influence:

[England’s] social fabric had been weakened and had become rigid. Her taxes and wage rates were incompatible with vigorous development, yet there was nothing that could be done about it. Keynes was not… in the habit of bemoaning what could not be changed… not the sort of man who would bend the full force of his mind to the individual problems of coal, textiles, steel, shipbuilding…. He was the English intellectual, a little deracine and beholding a most uncomfortable situation. He was childless and his philosophy of life was essentially a short-run philosophy. So he turned resolutely to the only “parameter of action” that seemed left… monetary management. Perhaps he thought that it might heal. He knew for certain that it would sooth–and that return to a gold system at pre-war parity was more than his England could stand. If only people could be made to understand this, they would also understand that practical Keynesianism is a seedling which cannot be transplanted into foreign soil: it dies there and becomes poisonous be- fore it dies.

[“Childless”] is a truly classless move given Keynes’s wife Lydia Lopokova’s two miscarriages–the best we can hope for Schumpeter is that his self-absorption in the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s had kept him from ever learning about them. There was when I was an undergraduate an oral tradition that Schumpeter’s “childless” was a sotto voce synonym for “homosexual”–I presume Himmelfarb picked that up from similar sources to those I heard it from.

But Schumpeter, at least, does not cite “In the long run we are all dead” as evidence for the proposition that Keynes’s “philosophy of life was essentially a short-run philosophy”. Instead, he simply asserts that Keynes’s “philosophy of life was essentially a short-run philosophy”.

Is there any evidence that Keynes’s “philosophy of life was essentially a short-run philosophy” that unjustly neglected the long run? Keynes would have denied it: Keynes would have said that he gave proper balance to the short run and the long run. But, he would have added, it is also the case–as Skidelsky quotes him in The Economist as Saviour–that:

Burke ever held, and held rightly, that it can seldom be right… to sacrifice a present benefit for a doubtful advantage in the future…. It is not wise to look too far ahead; our powers of prediction are slight, our command over results infinitesimal. It is therefore the happiness of our own contemporaries that is our main concern; we should be very chary of sacrificing large numbers of people for the sake of a contingent end, however advantageous that may appear…. We can never know enough to make the chance worth taking…

So here we have it: not Herrick or Marvell or decadent Bloomsbury. Instead, Edmund Burke. Not a heedless disregard for the future, but a sober acknowledgement of the limited power of the brains of jumped-up East African Plains Apes like us to even see the long-run, and a plea not to sacrifice those currently alive to the Dreadful Moloch of Utopian Fantasies of the Future.

Schumpeter has, I think, considerable explaining to do.

As does Hayek.

As does Himmelfarb.

The rest–the Fergusons and the McCraws and the Druckers and the Heilbronners and company? At the very least, they need to explain why they didn’t check their “In the long run we are all dead” quotes against the context, and why doing so did not then lead them to have an Inigo Montoya moment as they said: “wait a minute–this doesn’t mean what I thought it meant”.

[1] Himmelfarb, writing in 1960:

The familiar racist sentiments of Buchan, Kipling, even Conrad, were a reflection of a common attitude. They were descriptive, not prescriptive; not an incitement to novel political action, but an attempt to express differences of culture and colour in terms that had been unquestioned for generations. To-day, when differences of race have attained the status of problems–and tragic problems–writers with the best of motives and finest of sensibilities must often take refuge in evasion and subterfuge. Neutral, scientific words replace the old charged ones, and then, because even the neutral ones–“Negro” in place of “nigger”–give offense, in testifying to differences that men of goodwill would prefer forgotten, disingenuous euphemisms are invented–“non-white” in place of “Negro”. It is at this stage that one may find a virtue of sorts in Buchan: the virtue of candor, which has both an aesthetic and an ethical appeal…

That somebody could–in 1960–write of how “to-day… differences of race have attained the status of problems–and tragic problems” as opposed to 1920, when presumably differences of race were not problems? Feh!

Must-Read: : The Financial Crisis, Austerity and the Shift from the Centre: “Think of two separate one dimensional continuums…

…one economic, with neoliberal at one end and statist at the other, and the other something like identity. Identity can take many forms. It can be national identity (nationalism at one end and internationalism at the other), or race, or religion, or culture, or class. Identity politics is stronger on the right…. For the political right identity in terms of class can work happily with neoliberalism, but identity in terms of the nation state, culture and perhaps race less so…. When neoliberalism is discredited, this potential contradiction on the right becomes more evident… [as] politicians on the right use identity politics to deflect attention from the consequences of neoliberalism…. Identity has always been strong on the right, so it is a little misleading to see it as only something that the right uses in an instrumental way….

None of this detracts from the basic point that Quiggin makes: the apparent drift from the political centre ground is a consequence, for both left and right, of the financial crisis…. One interesting question for me is how much the current situation has been magnified by austerity. If a larger fiscal stimulus had been put in place in 2009, and we had not shifted to austerity in 2010, would the political fragmentation we are now seeing have still occurred? If the answer is no, to what extent was austerity an inevitable political consequence of the financial crisis, or did it owe much more to opportunism by neoliberals on the right, using popular concern about the deficit as a means by which to achieve a smaller state? Why did we have austerity in this recession and not in earlier recessions? I think these are questions a lot more people on the right as well as the left should be asking.

Job-hopping is, unfortunately, on the decline in the United States. While we don’t fully understand the reasons for the decline yet, we should start thinking about economic and policy changes that may help workers switch more readily between jobs. Which leads us to non-compete agreements.

Non-compete agreements are contracts between employers and employees that determine how long a worker has to wait after leaving a firm before he or she can go work for a competitor. Some of the logic behind non-competes makes sense, as employers might want to protect trade secrets or the agreements may give employers an incentive to invest more in their workers. But there’s mounting evidence that non-competes have expanded too far and pose a problem for workers and the U.S. economy.

A new report from the U.S. Department of the Treasury looks at the extent and impact of non-compete agreements in the labor market. For a labor market institution just now gaining significant attention from researchers and policymakers, non-competes are fairly common. According to one estimate, 18 percent of U.S. workers currently work under a non-compete and 37 percent have been subject to such an agreement at some point during their career. You might think that these agreements are mostly for highly educated or high-income workers, but 15 percent of workers without college degrees and 14 percent of workers making less than $40,000 a year are working under non-competes. As the infamous example of Jimmy John’s shows, it’s unlikely that these workers have trade secrets they’ll spill to their new employers.

So why are employers are using these kinds of agreements? One possibility is that employers want to hold on to the workers they invest in, so non-competes give employers the security to invest in the human capital of their workers. As the Treasury report notes, there is some evidence for this effect as the probability of firm-sponsored training increases in states where non-competes are enforced more, but only by 2.4 percent for high litigation occupations relative to low ones. Another possible reason is that workers aren’t aware of these agreements when they take a job and then the agreement is used as a means to suppress workers’ bargaining power and therefore their wages.

One way to sort out this question is to look at how wage growth across states that enforce non-compete agreements differs from other states. First, states that have stronger enforcement of non-competes have lower worker job mobility. Furthermore, stricter enforcement is associated with lower initial wages and lower wage growth over the source of one’s career. This second result is particularly troubling for the job-training story, because we’d expect wage growth over a career to be higher if non-compete enforcement increased training relative to areas where the agreements aren’t strictly enforced. Instead, the opposite happens, strengthening the argument that the agreements are about shifting bargaining power to employers.

But given this information, how should states reform these agreements moving forward? The Treasury report suggests reforms such as states specifying the exact extent to which the agreements can be enforced or making firms give “consideration” to workers in the form of payout. Or perhaps the agreements should be banned outright, as some commentators such as Jordan Weismann of Slate have argued. Regardless, whether we scale them back or end them outright, it’s clear the right direction is backward when it comes to non-competes.

Yesterday, the U.S. Department of Labor released data for February from its Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, or JOLTS—the lesser-known monthly report on the U.S. labor market. The dataset shows us some of the labor market dynamics that underlie numbers like net job creation. The survey tells us, for example, how readily workers are quitting or getting hired for jobs. It also tells us how many job openings employers are posting—a sign of labor demand as firms get ready to hire.

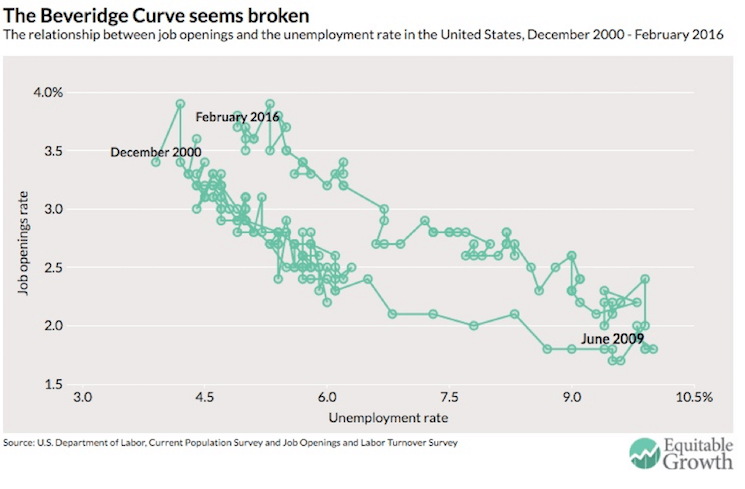

Over the course of the labor market recovery from the Great Recession, there’s been concern about the number of job openings. There seems to be a breakdown in the Beveridge Curve, the relationship between openings and the unemployment rate shown below. A shift outward in the curve indicates that firms are posting jobs at a rate they would have done at a lower unemployment rate before. Some economists interpret this shift as a sign that employers can’t find qualified workers.

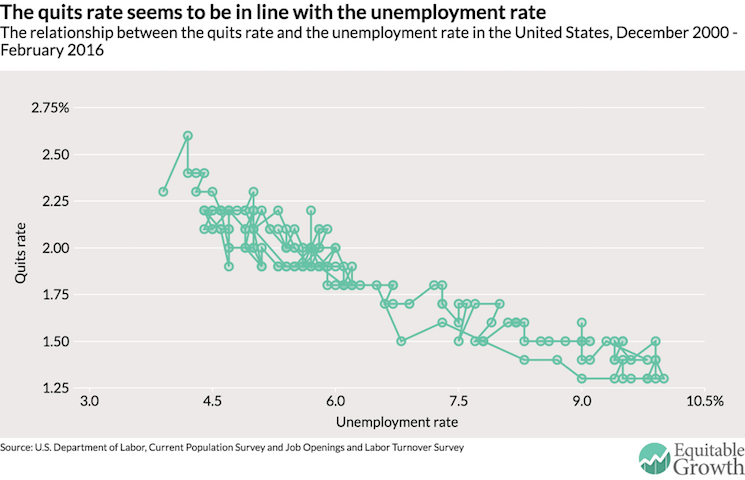

There’s reason to be skeptical, however, that this seeming shift is a sign of a skills breakdown. Let’s consider the relationship between some other JOLTS data and the unemployment rate.

First, let’s look at the quits rate, or the amount of workers voluntarily leaving a job. As Evan Soltas pointed out a couple of years ago, the relationship between the quits rate and the unemployment rate in the United States seems unchanged. Workers still seem to take a lower unemployment rate as a sign that they can get another job.

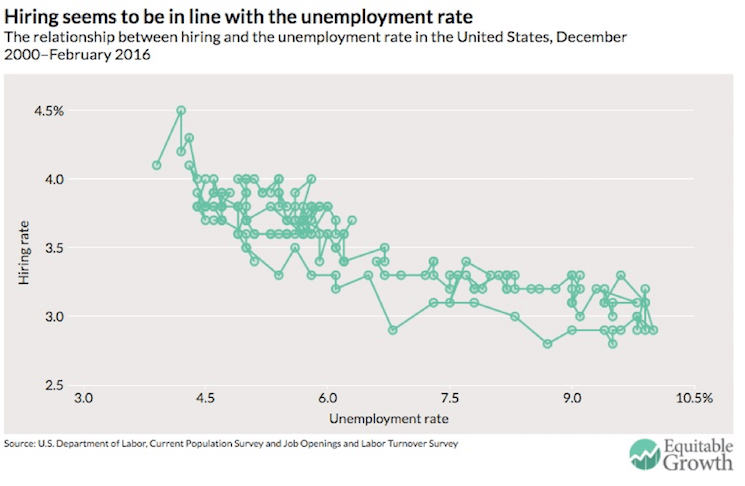

And data on hiring in the United States seems to back up their confidence. The hiring rate, or the percent of workers hired to new jobs, also seems to be following its previous relationship with the unemployment rate. So businesses are hiring workers at a rate in line with what we’ve seen at similar levels of the unemployment rate.

Firms seem to be hiring just as they were before, but they are posting jobs at a much higher rate. What could account for this disconnect between openings and hiring? It may be that shifts in worker bargaining power and increased profits are making employers more willing to post more jobs as they are less costly. Or it could be that employers are sending the wrong demand signals to workers or looking for future employees in the wrong ways. That’s a possibility that Byron Auguste, Managing Director of Opportunity@Work, floated in this interview with Equitable Growth’s Heather Boushey.

But let’s be clear about what a consistent relationship would mean for the labor market. This doesn’t mean that because unemployment has hit a healthy level, the labor market is strong. The points for recent months when it comes to quits and hires may be on the old curve, but they still could move up and to the left. U.S. wage growth is still subpar and underemployment is still quite high, meaning unemployment could go lower. That means we should also be looking for the quits rate and the hiring rate to go higher as well.

Must-Read: IMHO, long, long overdue…

: U.S. Unveils Retirement-Savings Revamp, but With a Few Concessions to Industry: “The Obama administration Wednesday rolled out a long-anticipated new rule aimed at transforming the way the financial industry delivers retirement-savings advice…

…Administration officials intend it as a direct attack on what they consider ‘a business model [that] rests on bilking hard-working Americans out of their retirement money,’ Jeff Zients, director of the White House National Economic Council, told reporters Tuesday. About $14 trillion in retirement savings could be affected… which requires stockbrokers providing retirement advice to act as ‘fiduciaries’ who will serve their clients’ ‘best interest.’ That is stricter than the current standard, which only says they need to offer ‘suitable’ recommendations…. Still… the financial industry… has fought the regulation since it was first proposed six years ago, [and] the final version includes a number of modifications… extending the implementation period… giving advisers more flexibility to keep touting their firm’s own mutual funds… curbing the paperwork and disclosure requirements…. Those fixes… could also give opposing companies and skeptical lawmakers more time to try to dilute the rule further or even try to kill it altogether under the new administration…. The new rule will be the centerpiece of President Barack Obama’s efforts to help middle-class families build retirement savings in an era when few have guaranteed pension benefits…

Must-Read: (2012): Is U.S. Economic Growth Over? Faltering Innovation Confronts the Six Headwinds: “Start by assuming that future innovation propels growth…

in per-capita real GDP at the same rate as in the two decades before 2007, about 1.8 percent per year…. Baby-boomer retirement (the reversal of the demographic dividend) brings us down to 1.6 and the failure of educational attainment to continue its historical rise takes us to 1.4 percent…

And adding 1.0%/year population growth gets us up to 2.4%/year as the U.S. economy’s future projected rate of economic growth.