Must-Read: : Smart Regulation and Economic Growth:

Category: Equitablog

Must-read: Kevin O’Rourke: “The Davos Lie”

Must-Read: From last winter…

: The Davos Lie: “As I write these words, the great, the good and the self-important are trudging around in the Alpine slush…

…sporting their best parkas and a variety of silly hats, and opining about the state of the world…. If there’s one thing that people agree about in Davos, it’s that globalisation is a Good Thing. And indeed, so it is, if the alternative is the autarky of the inter-war period…. If you are even slightly cosmopolitan in your ethical outlook, you should want this to continue. But it always makes sense to ask whether you can have too much of a good thing…. Who are the winners from globalisation, and who are the losers?… Developing economies with lots of cheap unskilled labour should export textiles and other labour-intensive manufactured goods to rich economies where wages are high. A second implication is that labour-intensive industries should go into decline in rich countries. A third implication is that this should lower the demand for unskilled workers, hence lowering unskilled wages and increasing inequality…. The debate has swung back towards the view that trade is important in explaining rising inequality, not only in rich countries, but potentially in developing economies such as Mexico as well….

I happen to think that inequality matters for its own sake, but even if you don’t agree with that value judgement you should still care about inequality, since it matters politically as well…. Unfortunately for Davos, globalisation’s losers are becoming increasingly hostile to trade (and immigration)…. Such attitudes are now beginning to influence politics in several rich countries…. Economists can tut-tut all they want about working-class people refusing to buy into the benefits of globalisation, but as social scientists we surely need to think about the predictable political consequences of economic policies. Too much globalisation, without domestic safety nets and other policies that can adequately protect globalisation’s losers, will inevitably invite a political backlash. Indeed, it is already upon us.

Weekend reading: “Working papers, interactives, and blog posts, oh my!” edition

This is a weekly post we publish on Fridays with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth has published this week and the second is work we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

The U.S. unemployment rate is close to many economists’ estimate of its long-run level. But accelerating wage growth isn’t here yet. What could explain the lack of takeoff? We investigate.

On Tuesday, we published the latest set of papers in the Equitable Growth working paper series. This month’s batch covers the macroeconomic effects of unemployment benefit extensions, the possible decline in intragenerational mobility, and how elections affect foreign direct investment.

When it comes to that second working paper, the result is quite surprising. Most of the research has found that mobility over a career has stayed relatively flat since the early 1980s. But the paper argues that one’s relative position at the beginning of their career has become more correlated with their position later on.

Last week, we released an interactive graph on trends in U.S. labor force participation that lets you select a specific time period to look at. This week, we released another edition that lets you select an age bracket to look at. Check it out.

Good news: The labor share of income in the United States is creeping upward. The bad news: This is partly due to productivity growth being so slow right now. So while labor may be gaining relatively, it’s in part because the economy’s long-run potential is slowing down.

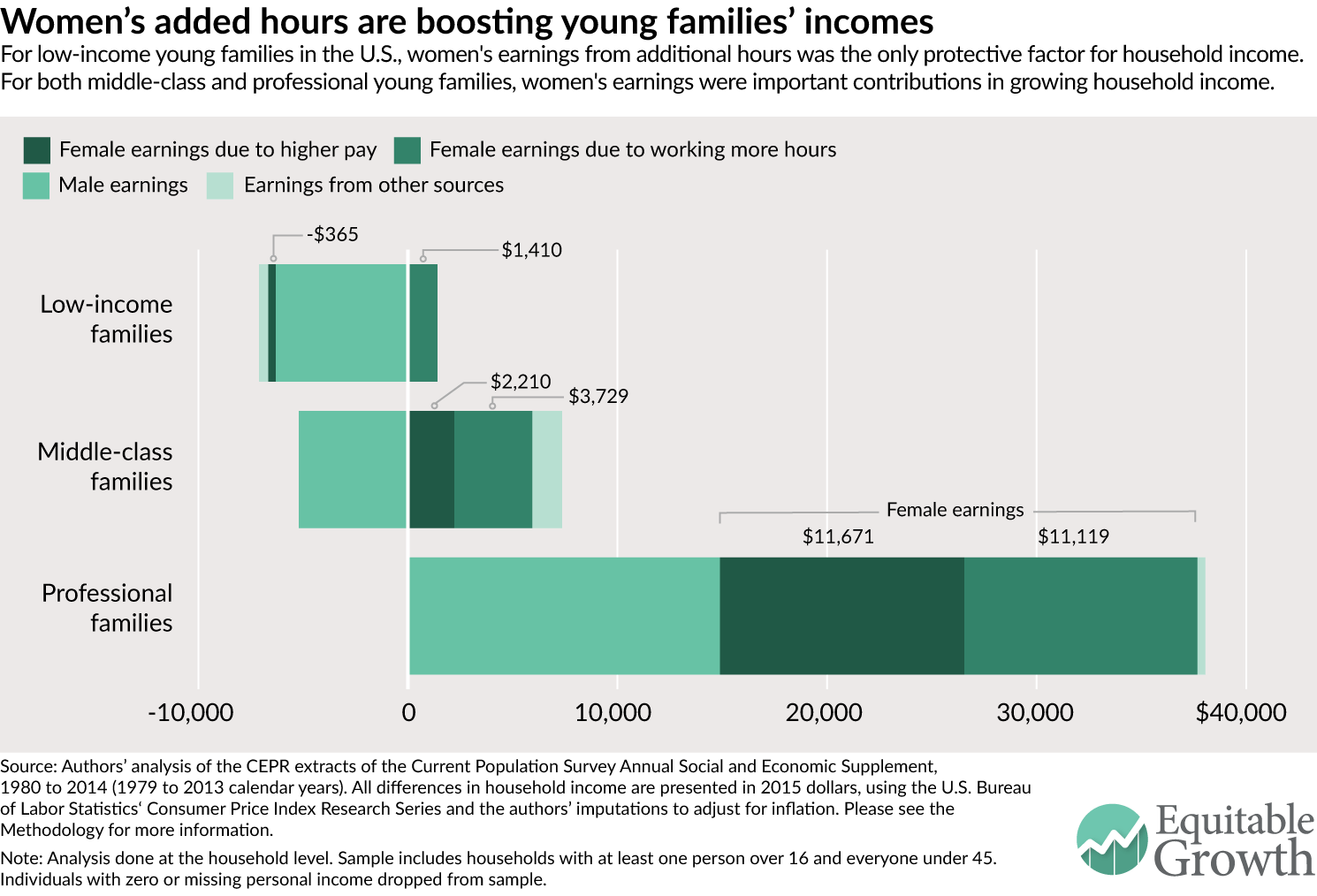

Heather Boushey and Kavya Vaghul continue their series of issue briefs on the importance of women’s working hours for family economic security. In this installment, the two look at trends in economic security for young families.

Links from around the web

The recovery in the U.S. housing market after the bursting of the bubble has been quite unequal. In fact, the increase in housing inequality has now reached its highest level since the Second World War. Jim Tankersley and Ted Mellnik dig into the data and the story. [wonkblog]

Gig economy companies—those like Uber and Airbnb that serve as digital platforms—have been heralded as many things, including forces for reducing income inequality. But new evidence indicates they do just the opposite, as Eric Morath reports. [real time economics]

Wealth can be transmitted from one generation to the next in a number of ways. Homeownership is one such way, as parents can help their children build up enough money for a down payment. But this doesn’t seem to happen as often for black Americans. Emily Badger looks into this finding. [wonkblog]

The increases in the U.S. labor force participation rate in recent months have spurred some hopes that labor market strength is pulling workers back into the labor force. But as Luke Kawa reports, there’s some evidence that this hasn’t happened yet, and the increases may be fleeting. [bloomberg]

As economists have started to contemplate the use of “helicopter money” to help boost economic growth, many have maintained that it’s just a form of fiscal policy run through a central bank. But Martin Sandbu disagrees with that framing. [free lunch]

Friday figure

Figure from “Garnering economic security is complicated for young families,” by Heather Boushey and Kavya Vaghul.

Must-read: Noah Smith: “Brad DeLong Pulpifies a Cochrane Graph”

Must-Read: Very welcome backup from the very-sharp and extremely hard-working newly ex-academic Noah Smith. I very much hope his new career path is very successful: it deserves to be…

: Brad DeLong Pulpifies a Cochrane Graph: “I’ve always been highly skeptical of John Cochrane’s claim that if we simply launched a massive deregulatory effort…

…it would make us many times richer than we are today. Cochrane typically shows a graph of the World Bank’s ‘ease of doing business’ rankings vs. GDP, and claims that… if we boost our World Bank ranking slightly past the (totally hypothetical) ‘frontier’, we can make our country five times as rich as it currently is…. Brad DeLong, however, has done me one better. In a short yet magisterial blog post, DeLong shows that even if Cochrane is right that countries can move freely around the World Bank ranking graph, the policy conclusions are incredibly sensitive to the choice of functional form….

DeLong… decides to do his own curve-fitting exercise. Instead of a linear model for log GDP, he fits a quadratic polynomial, a cubic polynomial, and a quartic polynomial…. Cochrane’s conclusion disappears entirely! As soon as you add even a little curvature to the function, the data tell us that the U.S. is actually at or very near the optimal policy frontier. DeLong also posts his R code in case you want to play with it yourself. This is a dramatic pulpification of a type rarely seen these days. (And Greg Mankiw gets caught in the blast wave.)…

You’d think Cochrane would care about this possibility enough to at least play around with slightly different functional forms before declaring in the Wall Street Journal that we can boost our per capita income to $400,000 per person by launching an all-out attack on the regulatory state. I mean, how much effort does it take? Not much. And this is an important issue. An all-out attack on the regulatory state would inevitably destroy many regulations that have a net social benefit. The cost would be high. Economists shouldn’t bend over backwards to try to show that the benefits would be even higher. That’s just not good policy advice.

Play with the R-code if you want to see how much a more flexible functional form wants to say that the U.S. has the optimal “Business Climate”: http://tinyurl.com/dl20160505c. I.e.:

Must-reads: May 6, 2016

- : A Springfield Education

- : Is Globalization Really Fueling Populism?

- : Black Lives Matter, Economic History Edition

Should-reads:

- : What Brexit surveys really tell us: “We can learn surprisingly little…”

- : Central Banking’s Final Frontier?

Must-read: Allen Guelzo: “A Springfield Education”

Must-Read: : A Springfield Education: “The Political Life of Abraham Lincoln: A Self-Made Man, 1809-1849 by Sidney Blumenthal

Simon & Schuster, 576 pp….

…This is a splendid book, and on a Lincolnian theme—the political Lincoln—that was in sagging need of a facelift…. Lincoln so closely resembled the Manchester School of Richard Cobden and John Bright that people spoke of Cobden as the British Lincoln, and Lincoln kept on his office mantelpiece a lithograph of Bright. Lincoln had had entirely too much of governmental intervening, over and over again, to protect the interests of slaveholders to find much charm in a government-directed economy….

Blumenthal’s work of building the context for Lincoln’s political activism in the presidential elections of 1836 through 1848 is a miracle of detail and his six chapters on Lincoln as a congressman in antebellum Washington are worth the price of the book alone. Blumenthal continually reminds us of what happened next door, as in this single ominous sentence: ‘Eight days after [Charles] Sumner was bludgeoned nearly to death, Lincoln stood on the stage at Bloomington to found the Illinois Republican Party.’ Never have we had such an exquisite warp of the ins and outs of political life in the 1830s and ’40s laid across the weft of Lincoln’s individual trajectory.

Rarely has a Lincoln biographer come to his task with such elegance of style…. Here is a great book, on a theme that too many people disdain to regard as great. That they are wrong about the theme, and wrong about Lincoln, is the burden of Blumenthal’s labor, and no one can come away from reading A Self-Made Man without understanding that, or without eagerly anticipating the ensuing volumes.

Must-read: Daniel Gros: “Is Globalization Really Fueling Populism?”

Must-Read: : Is Globalization Really Fueling Populism?: “Amid relative economic stability, rising real wages, and low unemployment rates [in northern Europe]…

…grievances about the economic impacts of economic globalization are simply not that powerful. Instead, right-wing populist parties like the FPÖ, Finland’s True Finns, and Germany’s Alternative für Deutschland are embracing identity politics, playing on popular fears and frustrations – from ‘dangerous’ immigration to the ‘loss of sovereignty’ to the European Union – to fuel nationalist sentiment.

In the southern European countries, however, the enduring impact of the euro crisis makes populist economic arguments far more powerful. That is why it is left-wing populist parties that are winning the most support there, with promises of, say, tax credits for low-paid workers. The most extreme case is Greece’s leftist Syriza party, which rode to victory in last year’s elections on pledges to end austerity. (Once in power, of course, Syriza had to change its tune and bring its plans in line with reality.)

Calling the rise of populism in Europe a revolt by the losers of globalization is not just simplistic; it is misleading. If we are to stem the rise of potentially dangerous political forces in Europe, we need to understand what is really driving it – even if the explanation is more complex than we would like.

Must-read: Chris Blattman: “Black Lives Matter, Economic History Edition”

Must-Read: : Black Lives Matter, Economic History Edition: “‘I use the individual-level records from my own family…

…in rural Mississippi to estimate the agricultural productivity of African Americans in manual cotton picking nearly a century after Emancipation, 1952-1965.

That is from Trevon Logan’s Presidential address to the National Economics Association.

Partly he calculates the productivity of his sharecropping ancestors relative to slave holding estates a century before (a persistent question in American economic history). But mainly he makes an argument for doing more qualitative interviews, which seems like an obvious point, except that systematic qualitative work is the exception in economic history (as it is in development economics):

That richer, fuller picture reveals that the work behind the estimates came to define the way that the Logan children viewed racial relations, human capital, savings, investment, and nearly every aspect of their lives. We learn not only about the picking process itself, but that chopping cotton may have been the most physically taxing aspect of the work. Similarly, the sale of cotton seed during the picking season was an important source of revenue for the family, and yet this economic relationship with the landowner was outside of the formal sharecropping contract. We also learn that it is impossible to divorce the work from its social environment{ an era in which Jim Crow, segregation, and other elements of overt racial oppression were a fact of life. Although none of the children has picked cotton in more than forty years, this experience continues to govern their daily lives and the way they interact with the world around them. Rather than being an item of the past, the work recorded in the cotton picking books continues to be a salient factor in their current economic decision-making.

Must-reads: May 5, 2016

- : Four Common-Sense Ideas for Economic Growth

- : The Elite’s Comforting Myth: We Had to Screw Rich Country Workers to Help the World’s Poor

Should-reads:

- : Implementing Monetary Policy Post-Crisis: What Have We Learned? What Do We Need to Know?

- : Ben Bernanke and Democratic Helicopter Money

- : The productivity slump and what to do about it

- : Li Hongzhang

- : For ‘Brexit,’ Like ‘Grexit,’ It’s Not About Economics

- : Another interactive look at changes in U.S. labor force participation

Labor gains in an era of low productivity growth?

The decline of the labor share of income in the United States—a topic well covered in this space—seems to have paused. As Neil Irwin points out at The Upshot, the data over the past year or so show a rising share of national income going to compensation of labor. At the same time, corporate profits as a share of income are on the decline. Irwin notes that corporate profits accounted for 14.2 percent of income in the middle of 2014 but were closer to 12 percent by the end of last year.

And yesterday morning, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics released data on productivity growth in the first quarter of 2016. The average cost of labor to make another unit of output, known as a unit labor cost, rose by more than 4 percent. Most of that gain was due to rising wages, but also because labor productivity declined by a percentage point.

So what are we to make of a rising labor share when productivity growth is close to zero?

Labor productivity growth has been quite terrible as of late. It declined at an annualized rate of 1.1 percent in the first three months of 2016, while its descent was steeper in the last quarter of 2015 at a 1.8 percent annual rate. This is in keeping with the longer trends of weak labor productivity growth in recent years and the declining total factor productivity growth.

The source of weak productivity growth is one of the most important economic questions right now, but it doesn’t seem like we’re going to definitively answer it soon. Jared Bernstein runs through some interesting possibilities, including a malfunctioning financial system, a slack macroeconomy, and dysfunctional government. But mechanically, the recent struggles of labor productivity may have to do with the industries where workers are being hired.

Since the start of the fourth quarter of 2015, the largest gains in employment have been in low-productivity industries such as leisure and hospitality, construction, and education and health services. More workers are producing things, but these workers are increasingly in industries where their labor isn’t producing that much more. A recent post by economist Dietz Vollrath shows that this trend has been going on since 2000, as workers have moved into industries that don’t just have low productivity but declining productivity growth as well. These are accounting exercises that can’t tell us the reason for these movements, but they’re instructive. Maybe we want to pay attention to the flow of workers and the dynamism of businesses.

In an era of low or even negligible productivity growth, policymakers may face some choices about what they’d like to achieve. At FT Alphaville, Toby Nangle lays out an “impossible trinity” of high corporate profits, steady inflation of 2 percent, and nominal wage growth of 4 percent. And while increasing productivity in the past hasn’t necessarily led to broadly shared wage growth, it’s definitely necessary. Hopefully, the recent trend is just an anomaly and we’ll soon see more sustained productivity growth. Fingers crossed.

So if inflation-adjusted wage growth exceeds productivity growth, then labor will get relatively more of output. But unless productivity growth jumps up, the absolute gains labor will see will be modest. A world where gains happen on both fronts definitely sounds more preferable.