Brad DeLong: Worthy reads on equitable growth, January 20–25, 2021

Worthy reads from Equitable Growth:

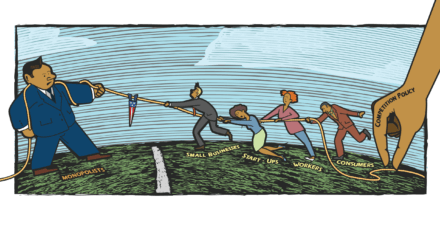

1. In previous decades, our claims to understand the relationship between the structure of the U.S. economy on the one hand and possibilities for equitable growth on the other have been a combination of guesses and platitudes. Now, finally, we are closing in on some real knowledge. The combination of the empirical turn in economics and the availability of massive new data sets collected by our information technology systems makes the promise for research progress very bright indeed. And Equitable Growth is on it. Read Christian Edlagan and Maria Monroe, “Understanding the role of market structure in equitable growth,” in which they write: How does market organization and firm behavior affect economic growth and its distribution? In this installment of Expert Focus, we highlight the industry- and market-specific analyses of researchers helping to advance our understanding of the complex relationship between industrial organization and market structure, antitrust law and competition policy, and economic inequality and growth … Leemore Dafny: “we continue to rely heavily on private insurers … [to] administer and sell commercial insurance … [and] because public insurance programs increasing rely on private insurers to deliver benefits to enrollees … Policymakers ought to look more closely …” Ying Fan: “There are too few products in the US smartphone market … The welfare effect of a merger may be underestimated when we take it to account the effect of the merger on product choice …” Nathan Miller: “If the objective was to prevent price increases for consumers, the MillerCoors merger should not have been approved. The reason is almost entirely do the coordinated effects …” John Van Reenen: “if girls were as exposed to female inventors as boys are to male inventors, the gender gap in innovation would fall by half …” Nancy Rose: “Government has likely retreated too far from the role it assumed almost 130 years ago with the passage of the Sherman Antitrust Act to ensure open, fair, and competitive markets.”

2. Back last spring, Equitable Growth warned about how unemployment insurance systems needed to be immediately changed to deal with what was about to come down the pike. In the Trump administration, of course, none of this work was actually done. But that the need for reform was ignored then does not mean that the reform is not still needed now. And now there is a chance for action, if somebody makes it a priority. Read Alix Gould-Werth, “Fool me once: Investing in unemployment insurance systems to avoid the mistakes of the Great Recession during COVID-19,” in which she writes: “To be able to respond nimbly to the next twists and turns in the coronavirus recession, policymakers should … increase the federal taxable wage base to the same level as the Social Security taxable wage base and index it to inflation so that states have adequate resources for program administration[;] redesign benefit extensions so that the program responds quickly and efficiently to macroeconomic changes[;] implement a standardized minimum benefit level and minimum benefit duration that are generous enough to incentivize workers to apply for benefits.”

3. Disability insurance appears to have much larger effects on social outcomes than the money amounts involved had led me to guess. I think this is because people use it as a last-gasp insurance program. It is highly unreliable. There are a great many people who ought to qualify for it and who, indeed, ought to have had it for years, but who did not consider it as an option until their financial affairs got dire. Nevertheless, many of them do not get benefits when they do apply. That is is a great shame. Read Manasi Deshpande, Tal Gross, and Yalun Su, “The effects of disability programs on financial outcomes,” in which they write: “A Social Security Administration rule … instructs government examiners to use more lenient standards for applicants who are above age 55 relative to those who are below age 55. A similar change in rules occurs at age 50 … We can attribute any differences in financial distress after the decision to the higher likelihood of being approved for disability benefits above the age cut-off … Being approved for disability benefits at the initial stage (before appeals) reduces bankruptcy rates by 30 percent over the next 3 years. Among homeowners, approval reduces foreclosure rates by 30 percent and reduces rates of home sales by 20 percent over the next 3 years … Many recipients use their disability benefits to stay in homes that they would have otherwise lost to foreclosure or sale … These effects are large relative to the size of disability benefits—on the order of $9,000 annually for the Supplemental Security Income program and $15,000 annually for the Social Security Disability Insurance program. Why are the effects so large? … Disability applicants apply for these programs after several years of increasing financial distress. At the time they apply, a large fraction of applicants are at risk.”

Worthy reads not from Equitable Growth:

1. The Federal Reserve continues to see itself as being all-in with respect to providing support for the U.S. economy. I confess that I wish that they were buying more bonds. I am not sure I understand why they have settled into this particular policy configuration. But every drop is very helpful. Read Steve Matthews, and Kyungjin Yoo, “Fed to Taper Asset Purchases in 2022 or Later, Say Economists,” in which they write: “Federal Reserve officials meeting next week are likely to put off any changes in their bond-buying program until 2022, when a tapering of purchases may begin, according to economists surveyed by Bloomberg News. About 88% of the 40 respondents to a Jan. 15-20 questionnaire said the Federal Open Market Committee’s next move will be to shrink purchases gradually rather than to increase their pace … “The release of pent-up demand, powered by monetary and fiscal policy, pushes the risks for both growth and inflation on the upside in the second half of 2021 and 2022,” economist Lynn Reaser of Point Loma Nazarene University said in a survey response … Many of the economists surveyed said they have altered forecasts in light of the fiscal stimulus, with virtually all of them raising their outlook for economic growth … Chair Jerome Powell as well as other Fed policy makers have suggested they don’t see any reason to change their bond buying or interest rates anytime soon. “Now is not the time to be talking about exit,” Powell said in a virtual speech Jan. 14. The FOMC last month pledged to continue to make $120 billion in monthly asset purchases until there’s “substantial further progress” toward employment and inflation goals. The economists in the Bloomberg survey don’t expect that to be met for some time … Nearly half of the economists are looking for a 2023 liftoff, while 40% see the first rate hike happening in 2024 or later … With super-easy monetary policy forecast, Powell might well get reappointed as chair by Biden when his term expires in 2022, according to economists. A second term is seen as likely to be offered, almost three-quarters of the respondents said.”

2. This still may be the last word on the minimum wage debate. It is nuanced. But it is not very nuanced. I continue to think that the sweet spot is clearly the proper coordinated mix of minimum-wage increases and expanded earned-income tax credits. Read Doruk Cengiz, Arindrajit Dube, Attila Lindner, and Ben Zipperer, “The Effect of Minimum Wages on Low-Wage Jobs,” in which they write: “We estimate the effect of minimum wages on low-wage jobs using 138 prominent state-level minimum wage changes between 1979 and 2016 in the United States using a difference-in-differences approach. We first estimate the effect of the minimum wage increase on employment changes by wage bins throughout the hourly wage distribution. We then focus on the bottom part of the wage distribution and compare the number of excess jobs paying at or slightly above the new minimum wage to the missing jobs paying below it to infer the employment effect. We find that the overall number of low-wage jobs remained essentially unchanged over the five years following the increase. At the same time, the direct effect of the minimum wage on average earnings was amplified by modest wage spillovers at the bottom of the wage distribution. Our estimates by detailed demographic groups show that the lack of job loss is not explained by labor-labor substitution at the bottom of the wage distribution. We also find no evidence of disemployment when we consider higher levels of minimum wages. However, we do find some evidence of reduced employment in tradable sectors. We also show how decomposing the overall employment effect by wage bins allows a transparent way of assessing the plausibility of estimates.”