Ahead of the June Jobs Day report, here is what the past three months of employment data say about the health of the U.S. labor market

The U.S. economy is now flush with many more jobs than prior to the onset of the COVID-19 recession in early 2020, and employment growth in the country continues to be exceptionally strong—much stronger than in previous early economic expansions. Ahead of the June Jobs Day report on July 7, here is what the employment data say about the health of the U.S. labor market.

Over the past three months the U.S. economy added an average of 283,000 jobs. The prime-age employment-to-population ratio—the share of workers between the ages of 25 and 54 who have a job—stands at 80.7 percent, its highest rate in more than two decades. And the national unemployment rate is low at 3.7 percent, although it registered an uptick in May. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

As of May 2023, most major U.S. sectors had fully bounced back from the pandemic shock, with the transportation and warehousing industry experiencing the largest percentage increase in employment since February 2020. With the exception of leisure and hospitality, government, and mining—and even as the information and utilities sectors have suffered net job losses in the past six months—all U.S industries are employing more workers now than prior to the onset of the pandemic. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

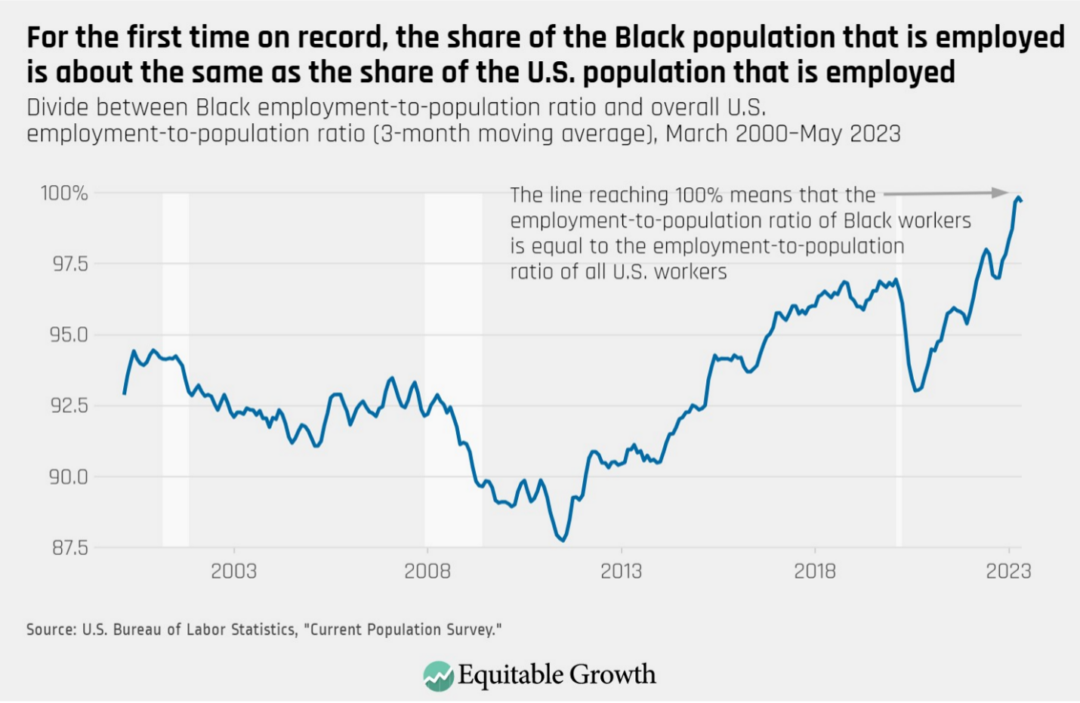

In addition, for about two years now, the strength of the labor market has translated into important gains for low-wage workers and workers of color, resulting in the narrowing of some economic disparities.

Starting in 2021 wage growth, for example, has been stronger for workers in the lower end of the wage distribution than for middle- and high-earning workers. The median Black worker and the median Latino worker also have experienced greater increases in pay than their White counterparts. And in the past year or so, there has been an unprecedented narrowing of the divide between the employment rate of Black workers and the employment rate of all U.S. workers. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

Wage growth seems to be slowing down most for some of the lowest paying jobs

When the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics releases the most recent employment data for the month of June this Friday, policymakers will have further information on what is happenings to the gains experienced by low-wage workers and workers of color. They also have further information on how the entire U.S. economy is settling into an expansion.

It is still unclear what workers’ enduring experiences will be in a post-pandemic labor market, but a number of economic indicators suggest that the jobs market is not going to be as hot as it was during the immediate aftermath of the COVID-19 recession, which ended in the spring of 2020.

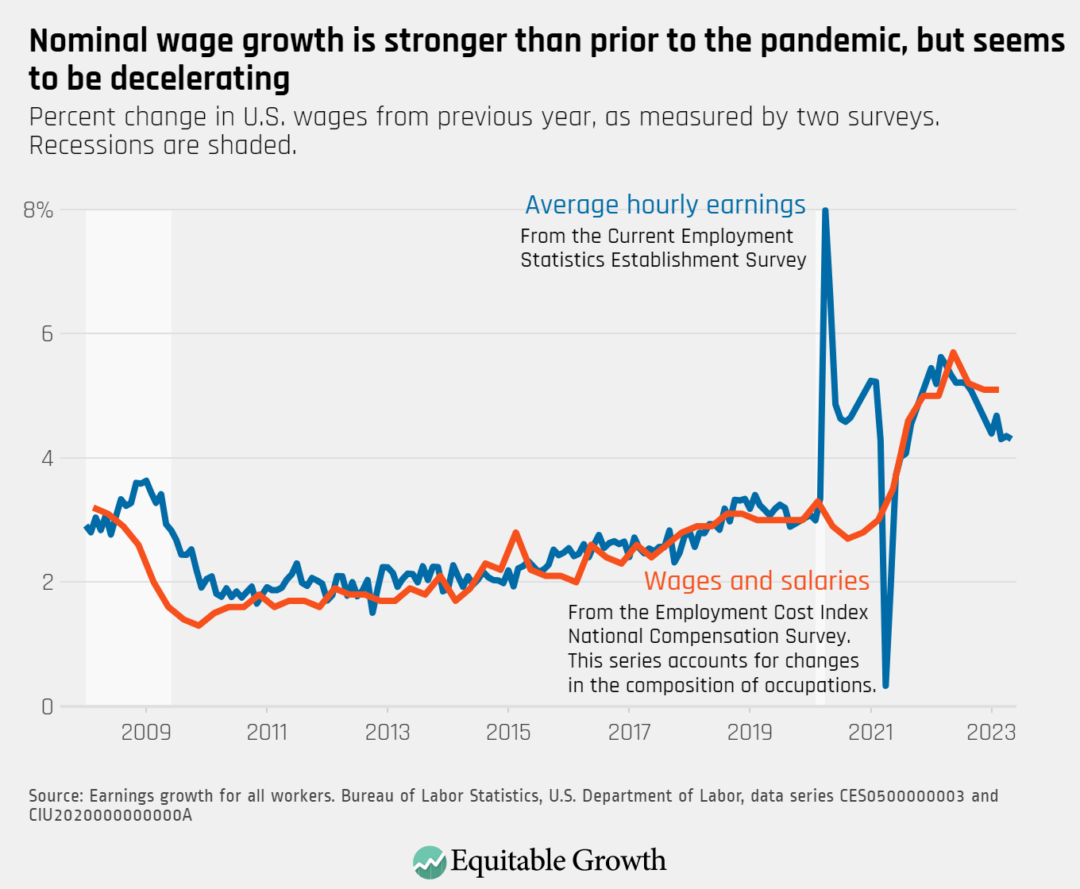

For instance, job growth has come down closer to its 2019 pace. The national quits rate—a good proxy for job-switching and an indicator that signals that workers are confident about their chances of finding a better job elsewhere—also has declined. The number of hires and job openings also are down year-over year. And overall wage growth is also now below its 2022 peak. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

While accompanied by a decrease in inflation, this slowdown in earnings growth seems to be especially pronounced for low-wage workers—many of the same workers who say that saw the biggest increases in pay in the immediate aftermath of the COVID-19 recession.

According to an analysis by Indeed, a job listing website, wage growth is tempering across the U.S. labor market but is decelerating much more for positions in the bottom of the pay distribution, including child care jobs. Overall, the posted wages of workers in low-wage occupations grew much more quickly than the wages in middle- and high-wage occupations throughout most of 2021 and 2022, but are now down and rising at a similar pace.

Most indicators show the U.S. labor market is very strong, but some economic disparities could widen anew if policymakers don’t secure post-pandemic gains for workers

The U.S. labor market has proven to be exceptionally resilient over the past two years, and it is normal and expected for increases in job growth to slow down as the labor market surpasses its pre-pandemic employment levels and different parts of the economy bounce back from the initial shocks delivered by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Yet further upticks in the national unemployment rate or a sharp deceleration in wage growth would hurt workers, particularly workers of color and workers holding low-wage jobs. These are the same workers who tend to benefit the most from a strong labor market and are hurt disproportionately during economic downturns.

Policymakers should ensure that the gains made by some of the most vulnerable workers in the U.S. economy are not contingent on the ups and downs of the business cycle. Rather, they should make sure that workers have sufficient bargaining power to secure decent pay, good working conditions, and benefit from the economic value they create.

One piece of proposed legislation that would go a long way towards reaching these goals is the Richard L. Trumka Protecting the Right to Organize, or PRO Act of 2023. The PRO Act would remove barriers to union organizing, put in place more effective measures to protect workers against violations of labor law by employers, and clarify workers’ right to engage in collective actions. Other measures that policymakers could adopt include raising the federal minimum wage and strengthening the U.S. system of income supports.

While the U.S. labor market might not always be as strong as it is now, measures that ensure that workers in the lower end of the pay distribution have access to fair pay and good employment opportunities would further narrow economic inequities and lead to stronger, broadly shared growth.