Dispatch from EconCon 2021: Addressing racial and gender stratification in the U.S. economy is key to an equitable and sustainable recovery

The 2-day EconCon 2021 conference, held virtually from October 6–7, featured speakers, panelists, and moderators from across the progressive policy and academic landscape. They were tasked by the co-hosts of the event, including the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, with examining “once-in-a-generation policy changes and transformative investments” to address U.S. economic inequality perpetuated most severely by the consequences of racial and gender stratification stretching back centuries and hobbling the U.S. economic recovery to this day.

The co-hosts put together an engaging schedule specifically to “underscore how fragile and unequal our economy has been, especially for communities of color, women, and other vulnerable people” in the wake of the coronavirus recession and the continuing pandemic in order to raise up policy solutions to “ensure an equitable, full recovery and a stronger, more sustainable economy for the future.” One central theme within this broad conference template that rose to the fore of the discussions were three words penned last summer by Janelle Jones—now the chief economist at the U.S. Department of Labor and previously a leader at Groundwork Collective, the leading co-sponsor of the EconCon 2021 event.

Those three words—“Black Women Best”—underpin Jones’ observation that when those who are last to recover from economic recessions—Black women—prosper equitably in the U.S. economy, then everyone will prosper in the process. These three words were repeated in multiple sessions and fireside chats over the course of the 2-day event.

One of the sessions, titled “Centering Black Women in our Economic Recovery to Ensure a Full Recovery for All,” zeroed in directly on this issue. The panel featured Taifa Smith Butler, Rebecca Dixon, and Michelle Holder—three Black women who are executive leaders of nonprofit organizations in the nation’s capital. Holder, the president and CEO of Equitable Growth, opened this session by fielding a question from moderator Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman, one of the co-founders of Sadie Collective: How are women of color experiencing the U.S. economy amid the pandemic?

Holder set the scene by noting that Black women on average earn the lowest wages and salaries yet can boast the highest rate of labor force participation in the country. She said this “conundrum” is the result of past racial and gender stratification, amplified over the centuries and exacerbated by the coronavirus recession and ongoing pandemic. The legacy of Black women’s enslavement, conditioned by their “exclusion from the cult of domesticity” embraced by White society for only White women in the post-Civil War era, especially in the Jim Crow South, still influences Black women’s employment and wealth-creating opportunities in the present.

“Black women kept working,” said Holder of the post-slavery era extending into today’s modern economy. “Black men were earning so little that Black women had to work to make ends meet,” she added. Similar conditions prevail today, where Black women, more often than White women, are either co-breadwinners or the primary breadwinners in their families.

Holder then juxtaposed Black women’s “strong attachment to the U.S. labor force” even when they earn the least in the U.S. economy, noting that they disproportionately hold the low-wage jobs that are now the most disrupted by the coronavirus pandemic. Given that a third of women who work in the United States are mothers, and that about 66 percent of Black children are raised in single-parent homes primarily by single moms—compared to about 25 percent of White children—disruptions to, or lack of, child care options raise particular challenges for Black working moms.

Holder’s co-panelist Rebecca Dixon at the National Employment Law Project added that Black women are held back in the U.S. economy because 90 percent of occupations are racially segregated due to the historical legacy of not just slavery but also sharecropping, property market redlining, and the agricultural and domestic work they did that was excluded—and still is excluded among some care professions—from Social Security. This occupational segregation, Dixon said, “is a perfect Venn diagram of discrimination past and present.”

Holder put a number on the cost of this gender and racial wage divide, which she terms the “double gap”: $50 billion a year in involuntarily forfeited earnings by Black women. This $50 billion (measured in 2017 dollars) probably accrued to a mix of corporate shareholders and executives, and to some extent to White workers, she said, though the breakdown isn’t clear. But the result is that Black women earn 60 cents on the dollar of what White men earn in the U.S. economy today.

Dixon then pointed out that the joint federal-state Unemployment Insurance program adds economic insult to discriminatory injury because Southern state UI programs were “in tatters” even before the pandemic; the majority of Black Americans currently live in the U.S. South.

Taifa Smith Butler of Demos then fielded a question from the Sadie Collective’s Opoku-Agyeman on policy solutions for this “double gap.” Smith Butler said that U.S. policymakers need to “reimagine economic democracy to give Black women the agency to make their own decisions without systems of oppression in place.” Black women, she said, need to get off the “hamster wheel creating wealth for other people.”

Holder then suggested a way to measure the economic well-being of Black women in the United States, harkening back to Janelle Jones’ “Black Women Best.” Holder said U.S. policymakers need to pay close attention to race and gender data on Black female employment and implement measures that move the country in the direction of more wage transparency in workplaces. Smith Butler added that disaggregation of employment and earnings data along race and gender lines must also be broken out by region.

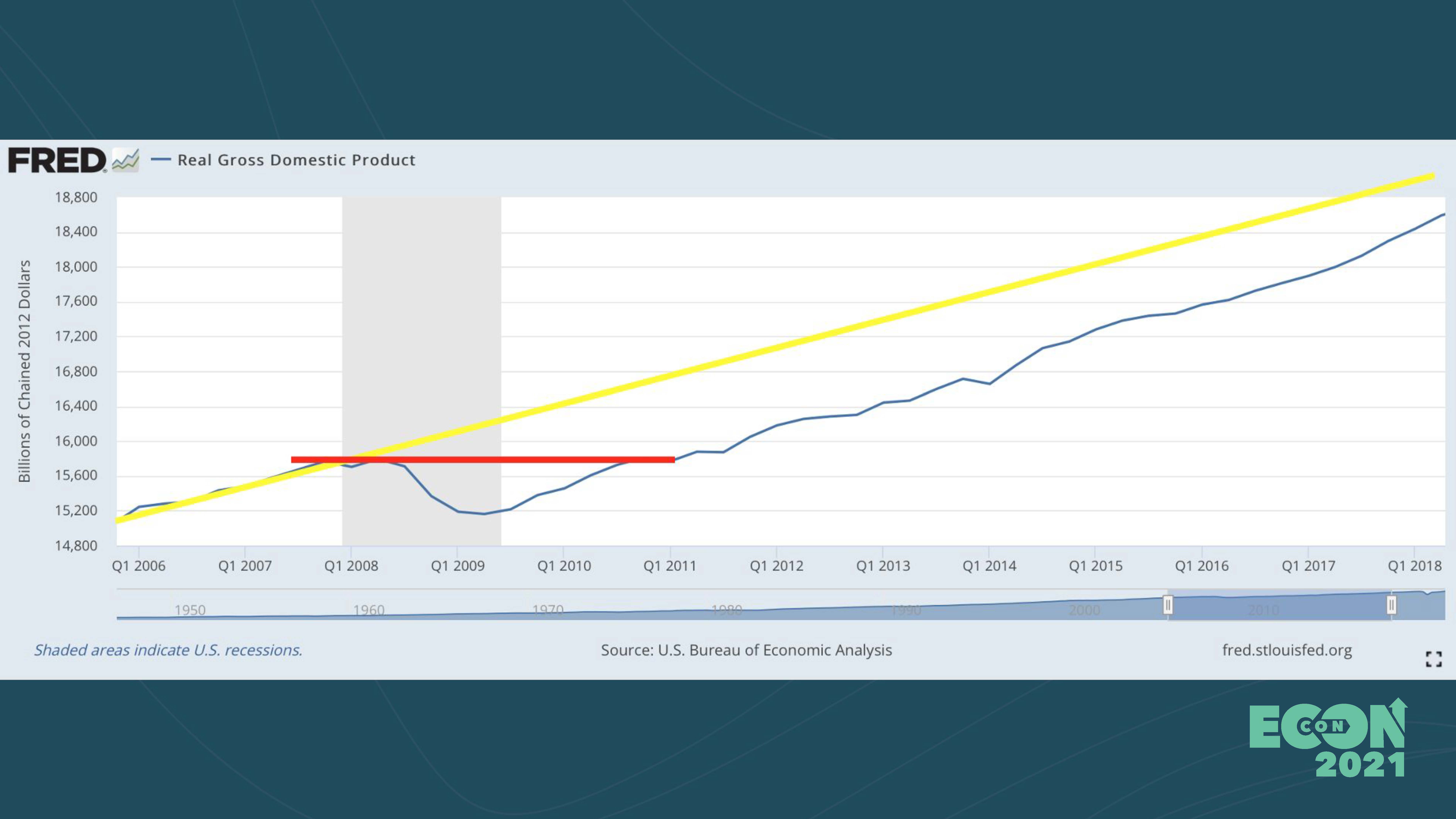

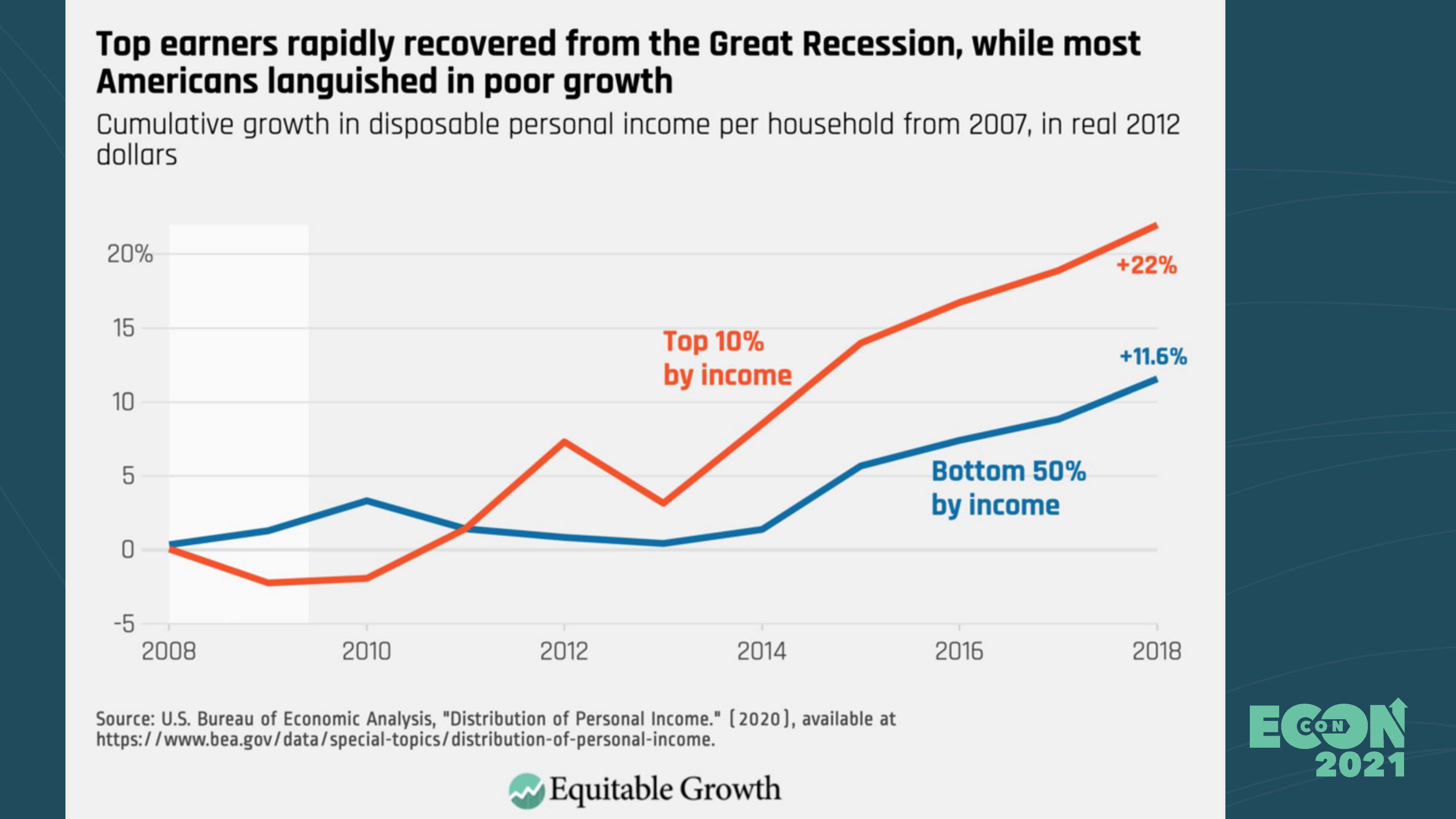

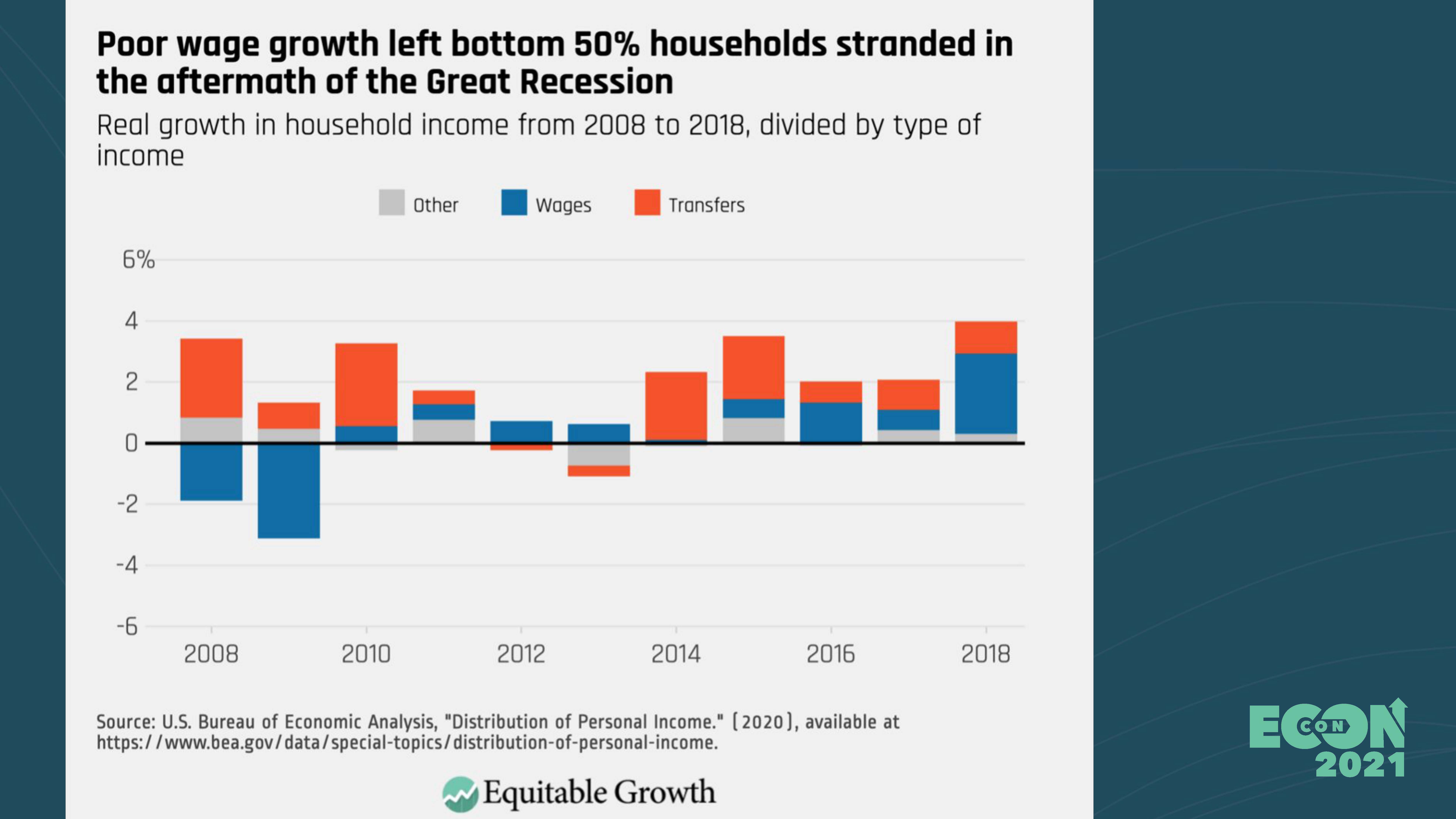

An important session on the second day of the conference added critical details to the need for economic data disaggregation by race, ethnicity, and gender in all its forms. The session, titled “Defining Success: Reimagining Data Measurement,” was moderated by Equitable Growth Director of Economic Measurement Policy Austin Clemens, with panelists Algernon Austin of the Center for Economic and Policy Research and Tracey Ross of PolicyLink. Austin set the table with three figures showing the inequitable economic recovery from the Great Recession of 2007–2009. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

The three slides show various dimensions of the slow recovery from the Great Recession to put the coronavirus recession of 2020 and its aftermath in focus amid today’s uneven economic recovery and continuing pandemic. Clemens and the two panelists then dove into a discussion of the indicators of racial stratification that are essential to discern in U.S. economic data, so that policy solutions can be identified to create strong, broad-based economic growth across the country. They all noted that there can be no understanding of persistent and rising economic inequality without acknowledging racial, ethnic, and gender inequality.

PolicyLink’s Ross said that policymakers, economists, and the press alike “need to reframe what it means to recover” from the coronavirus recession, so that “it’s not just back normal, which was not good enough for too many people.” Recovery, she said, needs to be about “fixing the broken economy, focusing on Black unemployment as one metric, on rural healthcare as another, and other indicators that show that the U.S. economy and society are stronger than they were before going into the crisis.”

The Center for Economic and Policy Research’s Austin noted that policymakers can’t improve what isn’t measured, and what is measured and reported on by the press doesn’t “reflect the lived experiences of average Americans.” He says that federal economic statistical agencies need to move away from average measures and adopt disaggregated ones that will capture more telling trends in Black workers’ employment rates. “Recovery is not the goal post, as that was a society with deep inequalities,” he said. “The Black unemployment rate goes from high, to really high, to high. It never goes to low.”

Clemens, Ross, and Austin discussed other key measures to capture the extent of racial stratification in the U.S. economy and then measure the results of new policy solutions in the subsequent data. They suggested a variety of new metrics, among them housing affordability disaggregated by race and income and by home rental and purchase prices, as well as a breakout of employment by wage category to see when low-wage jobs are recovering, compared to the already-recovering high-income and middle-income jobs. Then, there is the simple measure of paid sick leave. “Everyone is better off if everyone can get paid sick leave,” said Austin.

The panel ended with a discussion on regional economic inequality and its intersection with the baleful consequences of climate change on communities of color in particular. Clemens noted that the federal statistical agencies don’t always have the statistical power to monitor poverty and other economic outcomes in small geographic areas. And Austin pointed to racist and historically anti-Black policies in Mississippi that cascade across high levels of poverty and inequality, and are then exacerbated by poor infrastructure investment in mitigating climate change, which is causing more heat- and asthma-related health problems and more flooding that disproportionately harms Black Mississippians.

All in all, the 2 days of discussion and generation of policy ideas underscored the need for policymakers and economists alike to embrace new measures of economic inequality to understand how structural racism manifests in policies and institutions, and how this deep racial stratification in the U.S. economy and society can be reversed to create a stronger and more sustainable economic recovery for everyone.

As Tracy Williams of the Omidyar Network (another co-host of the event) said when opening one of the first sessions of the conference, “a key part of reimagining capitalism is to center Black women inside an equitable economy.” EconCon 2021 went a long way toward making the case that a smart way to define that success is to understand and measure how Black women are experiencing economic prosperity.