Weekend reading: The intersection of climate change and economic inequality edition

This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

Each month, we highlight a group of scholars doing ground-breaking work in specific areas of the social sciences in a series called Expert Focus as part of our commitment to build a community of scholars working to understand how inequality affects broadly shared economic growth. This month, Christian Edlagan, Michael Garvey, and Maria Monroe look at those scholars working at the intersection of climate change and economic inequality. These experts are attempting to assess the full effects of climate change across communities, income and wealth distributions, firms and workers, and the macroeconomy.

U.S. workers are frequently asked to sign noncompete clause as part of their work contracts, preventing them from taking their knowledge and talent to competing companies. Older theoretical arguments claim that these clauses are actually beneficial for workers and firms, citing the ideas that both parties agree to the noncompetes before signing and that noncompetes facilitate knowledge-sharing between firms and workers as well as firm-sponsored training of workers. David Balan explains in a recent Competitive Edge post that these arguments are weak and stand in tension with recent empirical evidence of the harms of noncompete clauses. Balan summarizes the findings in his accompanying working paper and then critiques each of the pro-noncompete arguments to show how these clauses are detrimental to workers. He demonstrates why they are actually largely a means for companies to extract additional value from their employees or to treat them poorly—and why policy solutions must treat noncompetes as such.

Employer concentration likewise has harmful, wage-suppressing effects on millions of U.S. workers, writes Anna Stansbury, and policymakers must respond accordingly. In a recent working paper by Stansbury and her co-authors, they propose a new method for estimating the causal effect of employer concentration, or monopsony, on wages. They find that monopsony lowers earnings for a significant set of workers, primarily those who have few options to move to other jobs or industries and those in lower-population areas. Their new method of measuring the causal effects of monopsony could have a significant impact on U.S. antitrust laws and labor market policy to combat excessive market power. Stansbury suggests that labor market regulators and antitrust enforcers respond with increased scrutiny on labor markets and use of policies that raise wages for workers directly, such as increasing the minimum wage or empowering unions.

In case you missed it: The deadline for Equitable Growth’s 2021 Request for Proposals is February 7, 2021. Equitable Growth supports research on whether and how inequality affects economic growth, and this year’s RFP has centered research on race and structural racism, as well as climate change.

Head over to Brad DeLong’s latest Worthy Reads, where he provides his takes on must-read content from Equitable Growth and around the web.

Links from around the web

President Joe Biden released details of his sweeping climate change plan, placing environmental justice at its core, report The Washington Post’s Juliet Eilperin, Brady Dennis, and Darryl Fears. President Biden’s unprecedented plan to treat climate change “as the emergency that it is” (according to a White House official) will also tackle the persistent racial and economic disparities in the United States and invest in low-income communities of color—which are disproportionately affected by pollution and climate change. Black, Hispanic, and Native American communities often are targeted for the placement of environmental hazards and eyesores, from power plants and landfills to hazardous waste depositories and trash incinerators, the Post reporters explain. This leads to disproportionate rates of disease and illness in these communities—which, in turn, leaves them more vulnerable to the worst effects of the coronavirus. President Biden’s climate plan aims to improve conditions for people of color so as to address the vast, longstanding inequalities and barriers these communities experience across the United States.

U.S. companies are using the pandemic to squash unionization efforts and reduce the power of collective bargaining, writes The Guardian’s Michael Sainato. Telling the stories of several groups of workers who believe they are shut out of employment by companies trying to break unions, Sainato shows how the coronavirus pandemic exacerbated various firms’ and industries’ use of lockouts, or work stoppages that are “initiated by the employer in a labor dispute where the employer uses replacement workers,” who are typically nonunion. In economic downturns, such as the coronavirus recession, lockouts reduce the power of unions and collective bargaining because of the higher availability of replacement workers due to high unemployment rates. Many of these workers are shut out for merely asking for better protections, hazard pay, and more favorable working conditions as they risk their lives during the pandemic.

During most economic downturns, both workers and investors face hard times. But during the coronavirus recession, only workers really felt pain, writes Robert Gebeloff in The New York Times’ The Upshot blog. This is largely thanks to the stock market, Gebeloff explains, which boomed despite the raging public health crisis and imploding job market—deepening existing inequalities in the U.S. economy. Just 1 in 6 American families report direct ownership of stocks, and the wealthiest 10 percent of Americans hold about 84 percent of all the value of financial accounts with stocks—meaning as the market soars, the wealthy get wealthier while their less well-off counterparts don’t share in the profits. The wealth divide in the United States is even wider than already-gaping U.S. income inequality, and racial disparities are even larger, Gebeloff reports, with Black Americans owning a disproportionately low share of assets and stocks.

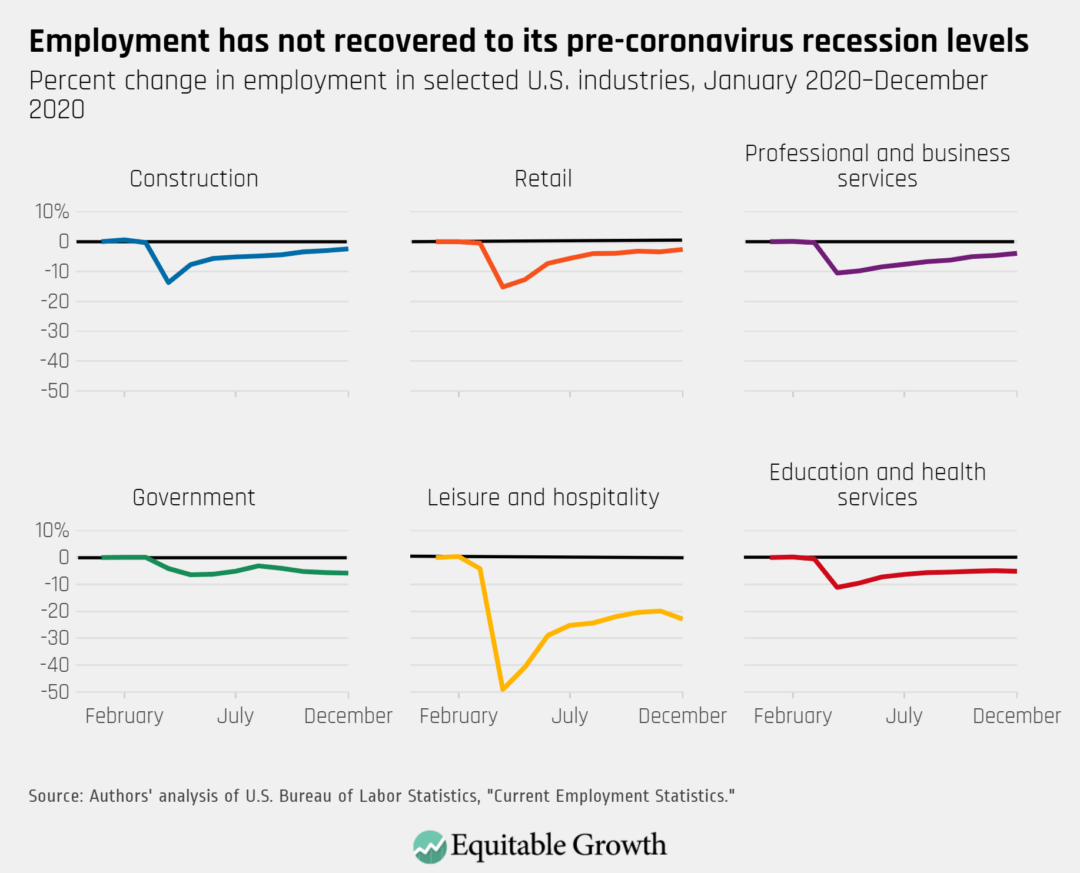

Friday figure

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s “Americans want green spending in federal coronavirus recession relief packages” by Parrish Bergquist, Matto Mildenberger, and Leah Stokes.