Weekend reading: Helping U.S. families stay out of poverty and build wealth edition

This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is probably best known for its role in eliminating barriers to political representation and voting for Americans of color at the height of the civil rights era. But a new working paper by Abhay P. Aneja and Carlos F. Avenancio-León shows that this signature legislation also worked to improve economic circumstances of Black Americans and other Americans of color. The co-authors’ research quantifies the connection between increasing political representation and reducing poverty, finding that between 1950 and 1980, the gap in median wages between Black and White workers in the South narrowed by around 30 percentage points, and that the Voting Rights Act was responsible for approximately one-fifth of that change. Aneja and Avenancio-León explain their study and its results in an issue brief, drawing a clear connection between Black voters’ greater political power and higher wages for Black workers in subsequent years, reducing poverty in the United States. They look at the various mechanisms that could have enabled the legislation to have this effect, and discuss the 2013 Supreme Court decision to weaken the law’s enforcement, which may be reversing the wage gains seen after the law was enacted.

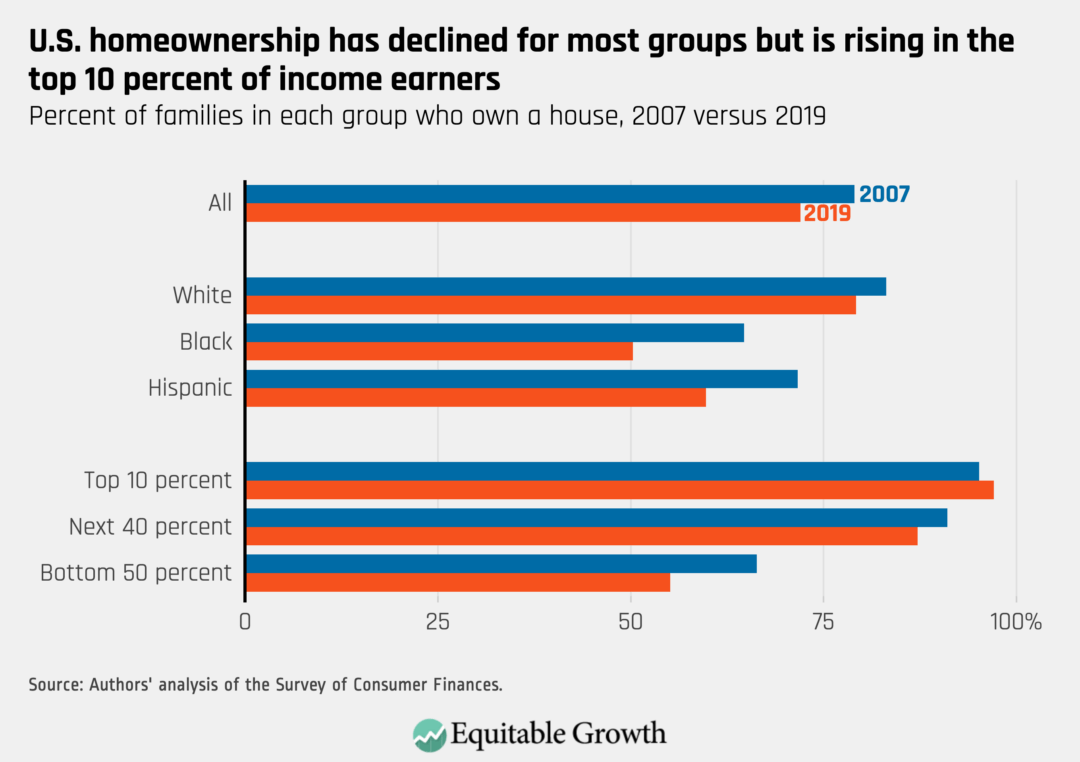

Homeownership in the United States for a long time helped White middle-class families build up their wealth, providing many of these families with opportunities to accumulate, over their working years, the financial cushion they need to support themselves upon retirement. Yet the Federal Reserve’s 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances suggests that this wealth-building opportunity is under threat for all U.S. households today. Austin Clemens and John Sabelhaus review the data, which show that the Great Recession of 2007–2009 and the sluggish recovery that followed it have pushed homeownership rates lower than they were for older generations at similar ages and phases in the lifecycle. Clemens and Sabelhaus look specifically at data for families with middle-aged heads of households because this group of people will be urgently in need of the financial security homeownership can provide in short order. They also examine the inequities in housing among this group along race and income lines, showing that White and wealthy families have higher rates of homeownership than their Black, Latinx, and less well-off peers. Clemens and Sabelhaus then propose several actions policymakers can take to protect these vulnerable families on the brink of retirement to ensure they are able to begin building wealth before exiting the labor force.

Equitable Growth is committed to building a network of scholars studying how inequality affects economic growth and stability. As such, every month, we highlight a group of scholars in various fields doing cutting-edge work in the social sciences. This month, Christian Edlagan, Aixa Alemán-Díaz, and Maria Monroe write about five scholars whose research looks at the diverse lived experiences of Latinx populations in the United States and how these experiences are often compared to those of Black Americans, who face similar barriers to economic and social equity.

Check out Brad DeLong’s latest Worthy Reads, in which he summarizes and analyzes recent content from Equitable Growth and around the web.

Links from around the web

Since the end of July, when emergency coronavirus aid relief provided in the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security, or CARES Act expired, up to 8 million Americans have slipped into poverty. Two new studies show how the aid worked to prop up many vulnerable families and how those families have fared since the money ran out—namely, that the poverty rate is now higher than it was before the onset of the pandemic, The New York Times’ Jason DeParle reports. The researchers found that the CARES Act relief kept more than 18 million people out of poverty, but that number has dropped now that it has expired. Despite what appears to be an improving job market, the studies show that poverty has continued to rise, indicating that the recovery is too sluggish to offset the negative effects of not renewing aid. Coupled with a recent uptick in Unemployment Insurance claims and rising cases of the virus across the United States, the economy is poised to falter again—and, DeParle writes, Congress is no closer to passing another, desperately needed stimulus package to support those most in need.

The connection between climate change and economic inequality is becoming more obvious with every passing day and is one of the biggest, most daunting challenges we face, writes The Atlantic’s Vann R. Newkirk II. Rising temperatures are more likely to affect poorer regions of the world, while wealthier areas—which contribute more to climate change via higher emissions—are mostly spared the worst effects of this warming or are easily able to avoid them. Sweltering heat levels also hit lower-income workers, such as farm and field hands, factory workers, and those in construction, harder than their more economically and geographically mobile peers, expanding wealth disparities even further, killing some people and not others, and fomenting conflict within many, and even between some, countries. Rising temperatures also exacerbate racial wealth and health divides, reinforcing structural racism and discrimination, and impacts Black and Latinx communities in the United States more than White areas. In short, Newkirk writes, in the long, hot century ahead, “the heat gap will be a defining manifestation of inequality.”

In the wake of lockdowns, quarantines, and stay-at-home orders earlier this year that most affected restaurants and the service industry in the United States, many small businesses have had to change their operations and business models to stay afloat. Even as some states and cities are now scaling back their restrictions on public gatherings, many people won’t return to their pre-coronavirus habits until they feel safe going out, meaning many of these businesses will continue struggling for months to come. One lifeline for many of them has been online crowdfunding websites, writes Vox’s Rebecca Jennings. But, Jennings continues, the fact that small businesses—the backbone of many U.S. cities, both small and large—have had to use these methods is clear evidence of the lack of public safety net protections for employers and employees alike. Though the Paycheck Protection Program, for instance, was intended to help those companies in this exact situation, many small businesses were excluded from the program for various reasons, and access was further limited for entrepreneurs of color, who faced significant barriers to entry. Crowdfunding and haphazard innovative solutions to coronavirus restrictions, such as makeshift outdoor dining patios and curbside pickup, will only work for so long, Jennings concludes, especially with winter around the corner. Policymakers must act to support the restaurant industry so that no more of these vital local businesses have to shutter permanently.

Friday figure

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s “Can policymakers reverse the unequal decline in middle-age U.S. homeownership rates?” by Austin Clemens and John Sabelhaus.