Five ways to understand Black Women’s Equal Pay Day

Today is Black Women’s Equal Pay Day. This is the day until when Black women have to work, from the start of 2019 through August 2020, to earn as much as White men earned in 2019 alone. In dollars and cents, Black women who work full-time, year-round earn 62 cents for every one dollar full-time, year-round White men workers earn. Lower earnings year-over-year means a lower level of well-being and increased economic risk in a downturn.

Read our work for Black Women’s Equal Pay Day 2021 here:

Black women face unique barriers at the intersection of race and gender in the U.S. labor market. In a Equitable Growth working paper, titled “Returns in the labor market: A nuanced view of the penalties at the intersection of race and gender,” Mark Paul of the New College of Florida, Khaing Zaw of Duke University, Darrick Hamilton of The Ohio State University, and William Darity Jr. of Duke University find that Black women’s pay disparities are greater than the sum of racial pay disparities and gender pay disparities. In their words, “Black women face a different gender penalty than White women, and different race penalties than Black men.”

To dig in deeper, we answer five questions about why Black Women’s Equal Pay Day falls more than 7 months into 2020 and what to do about it:

- What is the role of anti-discrimination enforcement when a large portion of the lower pay received by Black women is due to discrimination, compared to the entire population of women workers?

- How much are Black women disproportionately crowded into low-wage occupations?

- How do structural barriers that Black women face increase employers’ monopsony power to exploit workers?

- How can rejuvinating labor institutions and fostering worker power can help Black women share in the economic growth that they help create?

- How can labor market policies such as expanding and increasing the minimum wage disproportionately benefit Black women workers?

The answers to these questions demonstrate why Black women have achieved important gains in the U.S. labor market yet still face significant pay disparities due to persistent systemic discrimination. Increasing worker power through collective action and raising the minimum wage are two other critical steps needed to help close the persistent pay gap faced by Black women.

Anti-discrimination enforcement is critical to ensuring Black women earn their fair share

In their working paper, Paul, Zaw, Hamilton, and Darity find that more than half of the wage divide faced by Black women is not explained by human capital variables. This means that Black women with equivalent education, work experience, occupations, and other factors earn 20 cents less per dollar than a similar White man worker due to no discernible factor, or is the result of overt discrimination.

As one of the many victories of the Civil Rights movement, in 1965, the U.S. federal government created the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, the agency in charge of enforcing laws against workplace discrimination on the basis of race and sex, along with other protected individual characteristics. Research shows that as anti-discrimination enforcement became more active in the mid-1960s, the earnings of Black workers—and especially those of Black women workers—increased at a faster pace than the earnings of their White counterparts.

Yet the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission’s budget has declined consistently since the 1980s. Its number of employees fell by 42 percent between 1980 and 2018. The weakening of the agency’s ability to enforce anti-discrimination laws might be especially damaging for Black workers, who are more likely than any other racial or ethnic group to report facing discrimination at work or when applying for a job. An analysis by the National Partnership for Women and Families shows that between fiscal years 2011 and 2015, 28.6 percent of the charges of pregnancy discrimination filed with the Equal Employment Opportunity Comission were by Black women, despite representing only 14.3 percent of all women workers.

Occupational segregation results in Black women being crowded into low-paying jobs

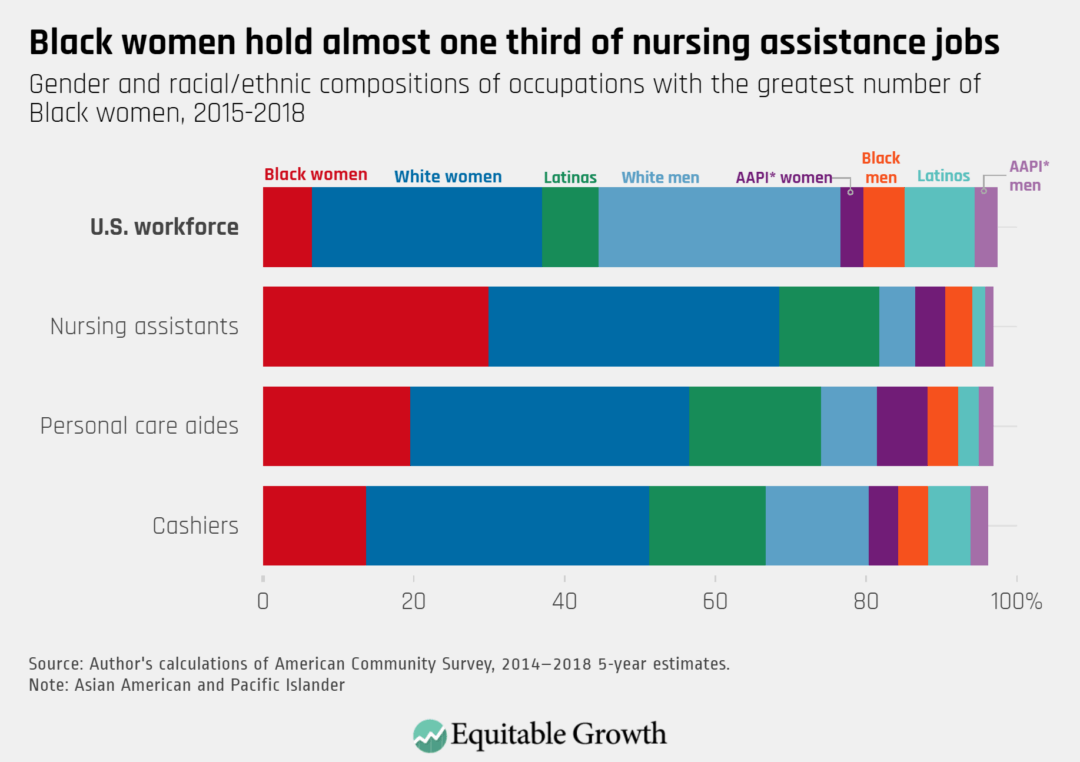

Occupational segregation contributes to a significant proportion of Black women’s pay disparities. It accounts for 28 percent of the intersectional wage gap that Black women face, ranking second as a contributing factor after unexplained causes or discrimination. The proportion of women in an occupation reduces the earnings for workers in those jobs, yet even when controlling for education and work, and due to the devaluation of jobs associated with women, the penalty associated with working in women-dominated occupations is greatest for Black women. Case in point: The median wage of nursing assistants was only $13.23 in 2017—a profession where Black women are nearly one-third of the sector’s workforce. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

In forthcoming research, Michelle Holder of John Jay College and Thomas Masterson of the Levy Institute reweight the distribution of workers across occupations to be representative of the workforce to determine the degree to which pay disparities between demographic groups are the result of over- or underrepresentation in high- and low-paid occupations. They find that when looking at Black and White workers by gender, Black women women face the greatest earnings penalty due to being crowded into lower-paying jobs and White men receive the greatest earnings bonus due to being crowded into higher-paying jobs.

Monopsony has reinforced the ability of employers to exploit Black women workers

As the U.S. labor market becomes less competitive, stifling wage growth, Black women may be increasingly exploited by employers across the labor market. In a new Equitable Growth working paper, titled “Discrimination and Monopsony Power,” Equitable Growth’s Director of Labor Market Policy Kate Bahn and Mark Stelzner of Connecticut College model how the historical and current barriers that Black women face across society limit how they can search for jobs, which, in turn, can give employers monopsony power to undercut wages. In the paper, the authors model how racial wealth disparities mean it is harder for Black and Latinx workers to leave their jobs in search of better ones, and gendered household responsibilities mean that breadwinner mothers may accept suboptimal jobs that allow for them to manage family care needs.

These phenomena lower the labor supply elasticity (economic parlance for the extent to which workers respond to changes in wages) of Black women. This is why it is possible and profitable for employers to offer lower wages than what would exist in a competitive labor market.

This theoretical model of how monopsony reinforces racial, ethnic, and gender wage discrimination not only aligns with the empirical evidence but also supports the findings of Paul, Zaw, Hamilton, and Darity, showing that the intersection of race and gender is multiplicative, so greater than the sum of individual racial and gender wage disparities.

Fostering worker power can help boost Black women’s wages

The increase in monopsony power, which reinforces persistent pay disparities experienced by Black women, is at least partially the result of the dismantling of institutions that support unionization and worker power. Black workers have higher rates of unionization compared to White and Latinx workers, and union wage premiums are stronger for Black workers and particularly for low-wage Black workers. But declining union density over time means that union wage premiums are less able to offset wage inequality.

In “Discrimination and Monopsony Power,” Bahn and Stelzner show that increasing institutional support for collective action reduces the ability of employers to exploit workers along racial, ethnic, gender, and intersectional lines. And the converse is also true—attacks on labor unions can disproportionately harm Black women, such as the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Janus v. American Federal, State, and County Municipal Employees limiting the ability of unions to collect dues in the public sector, where Black women are overrepresented. Jake Rosenfeld of St. Louis University and Meredith Kleykamp of University of Maryland find that, among women workers, Black-White wage divides would have been between 13 percent and 30 percent lower than they are today if deunionizaton had not occurred to the level it has in the United States.

Fostering worker bargaining power is particularly important for Black women workers, but there is still overall progress that needs to be made in organizing occupations with low levels of bargaining power, such as domestic workers, who are disproportionately Black women. Organizing among Black domestic workers in the 1970s led to the inclusion of more domestic workers in minimum wage and overtime protections in the 1974 amendment to the Fair Labor Standards Act, yet many are not covered and have limited worker power to engage in collective action.

Encouraging and protecting the ability of workers to organize with broad policies such as the Protecting the Right to Organize, or PRO, Act, and policies targeted at jobs with a high share of Black women, among them the proposed federal Domestic Workers Bill of Rights, would balance the ability of employers to exploit Black women and help close this intersectional wage divide.

Increasing and expanding the minimum wage helps close the wage divide that Black women suffer

New research shows how effective minimum wage legislation can be in alleviating pay disparities along the lines of race. Ellora Derenoncourt at Princeton University and Claire Montialoux at the University of California, Berkeley find that the expansion of minimum wage coverage to sectors such as agriculture, hotels, restaurants, schools, nursing homes, and hospitals through the 1966 Fair Labor Standards Act played a major role in narrowing the earnings gap between Black and White workers during the Civil Rights era. The pay divide narrowed because Black workers were overrepresented in those newly covered sectors and the adoption of the minimum wage led to a much greater raise for Black workers than for their White counterparts.

This extension of the minimum wage, Derenoncourt and Montialoux show, explains more than 20 percent of the decline in the Black-White earnings divide between the late 1960s and early 1970s.

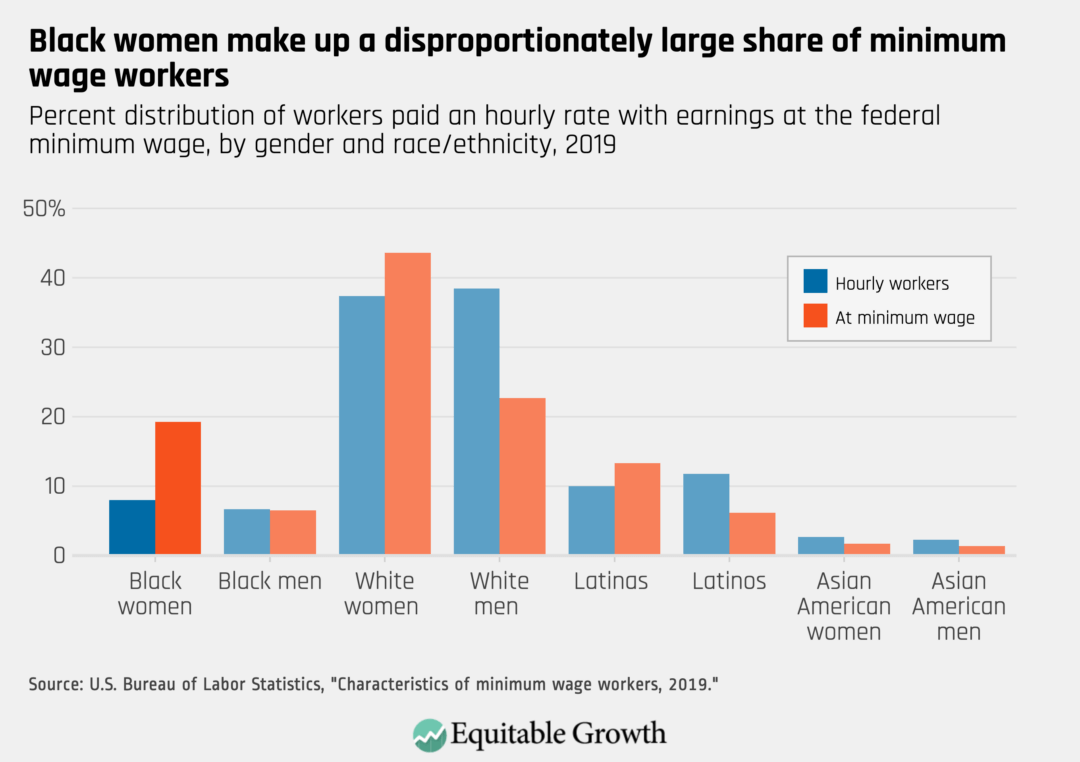

The problem is that the federal minimum wage is still the same today as it was in July 2009, standing at $7.25 per hour. Even though many states acted to boost their minimum wages over the past few years, Black women remain overrepresented among minimum wage workers and are particularly hurt by the long absence of a hike in the federal miniumu wage. A recent analysis by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics finds that even though Black women make up 8 percent of all hourly workers, they represent 19.3 percent of workers with wages at the federal minimum and 8.8 percent of those below it. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Conclusion

Black women have, without a doubt, increased their rates of college completion, experienced declining occupational segregation, and achieved other types of gains that the human capital model purports would help to close the intersectional wage divide, yet significant pay disparities remain due to enduring systemic discrimination. In this column, we examined some of the strides Black women have made in the U.S. labor market, alongside the structural barriers that are preventing them from reaching pay parity. Even though the traditional human capital model explains some of the disparities and helps map some policy solutions, this model is inadequate in helping us understand why pay disparities remain so persistent and how we can finally close the wage divide. Increasing worker power through collective action and raising the minimum wage are two other critical steps needed to help close the persistent pay gap faced by Black women.