The federal minimum wage today stands at $7.25 per hour, unchanged since 2009 despite rising prices and rising nominal wages for other workers. Indeed, the purchasing power of the minimum wage has been deteriorating for decades. Without legislative action by Congress every year—a very difficult policy endeavor—the minimum wage for the nation will continue to stagnate. This issue brief examines the importance of raising the minimum wage to boost broad-based U.S. economic growth amid rising U.S. income inequality and a still-tepid economic recovery. Policymakers need to understand the broad benefits of raising the minimum wage and whether there are any trade-offs to be made.

Sure to be in the spotlight are questions about whether and how the minimum wage:

- Improves family incomes, especially in women-led households

- Affects job prospects for low-wage workers, the unemployed, and youth entering the labor market

- Boosts broad-based aggregate economic demand

- Should be indexed to the rate of inflation or other macroeconomic indicators

This issue brief provides the most relevant details about the minimum wage, drawn from the Washington Center for Equitable Growth’s broad network of academic scholars studying this issue.

Download FileThe importance of raising the minimum wage to boost broad-based U.S. economic growth

Read the full PDF in your browser

What are the effects of raising the U.S. minimum wage?

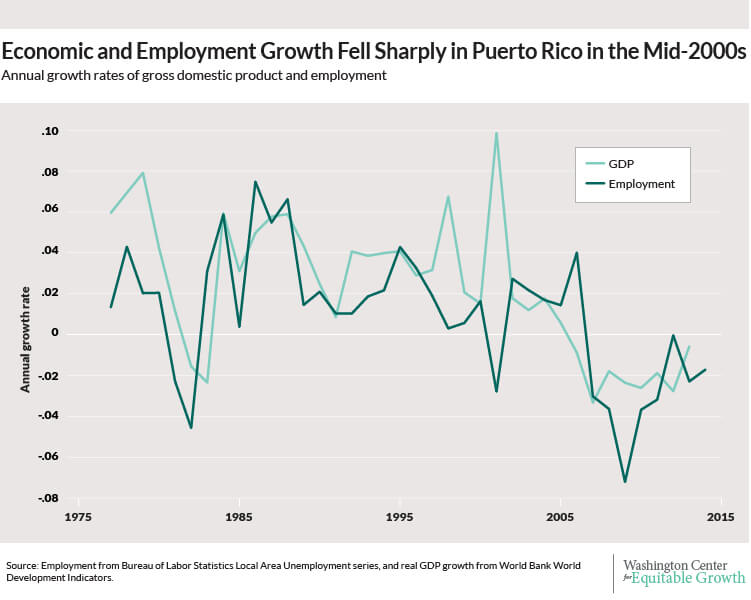

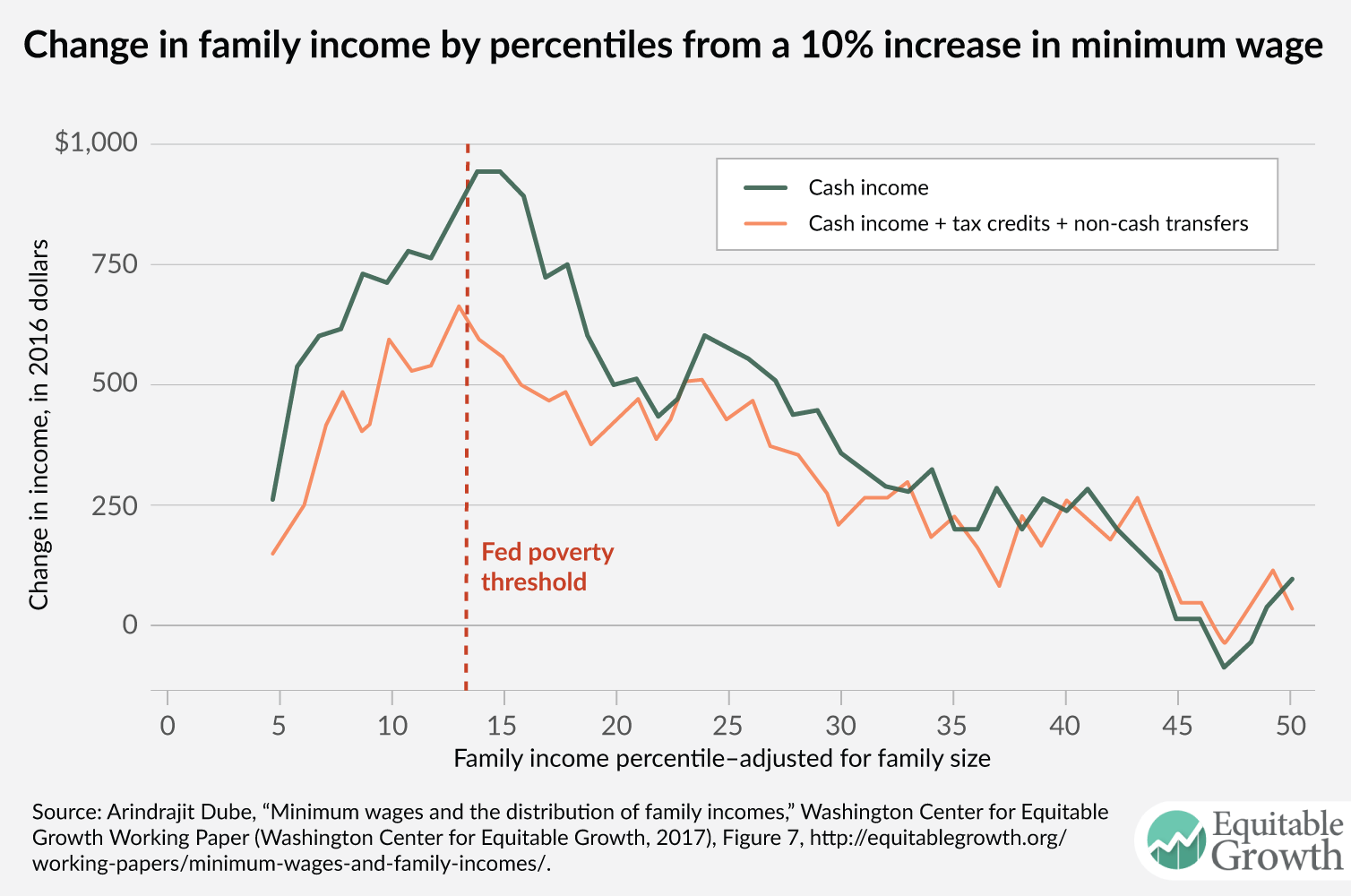

In a new working paper and issue brief for the Washington Center for Equitable Growth on the overall economic benefits of increasing the minimum wage for U.S. households, associate professor of economics Arindrajit Dube at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, finds:1

robust evidence that higher minimum wages lead to increases in incomes among families at the bottom of the income distribution, and that these wages reduce the poverty rate. A 10 percent increase in the minimum wage reduces the nonelderly poverty rate by about 5 percent. At the same time, I find evidence for some substitution of government transfers with earnings, as evidenced by the somewhat smaller income increases after accounting for tax credits such as the Earned Income Tax Credit and noncash transfers such as Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. The overall increase in post-tax income is about 70 percent as large as the increase in pretax income.

Dube concludes that a “substantial increase in the federal minimum wage can play an important role in reducing poverty and raising family incomes in the United States at the bottom of the income ladder while reducing the use of public assistance.” He notes that “the loss in cash and noncash transfers and tax credits among those who would benefit the most from minimum wage increases is likely to dampen some of the benefits, especially among those around the poverty line, yet the resulting public savings could be ploughed back into further shoring up the safety net—in turn further increasing the complementarity between minimum wages and income support for raising the incomes of families at the bottom of the income ladder.”

Dube says “these findings are consistent with some individuals losing eligibility for benefits as a result of increased income.” He notes that “typically, eligibility for supplemental nutrition assistance, for example, requires income to be less than 130 percent of the federal poverty threshold, which for this population binds just under the 15th percentile. On average, those in the bottom quartile of the income distribution can expect an approximately $525 increase in annual income from the minimum-wage policy; the gains are largest around the 15th percentile.” (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

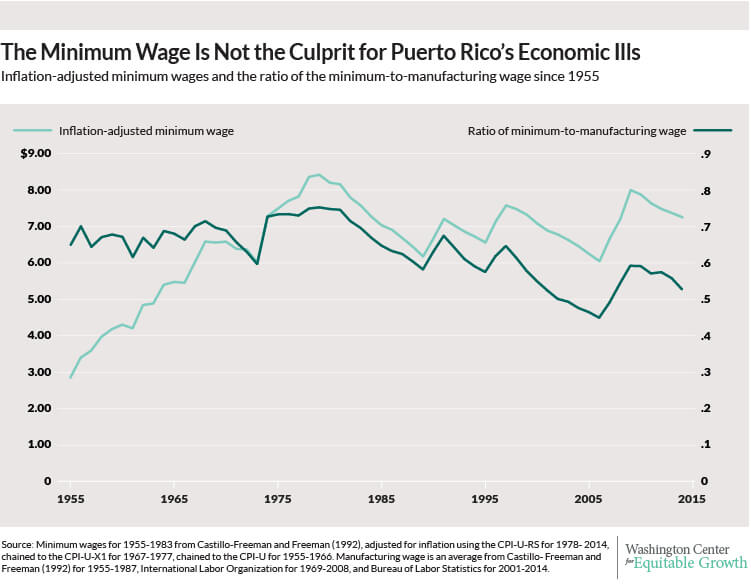

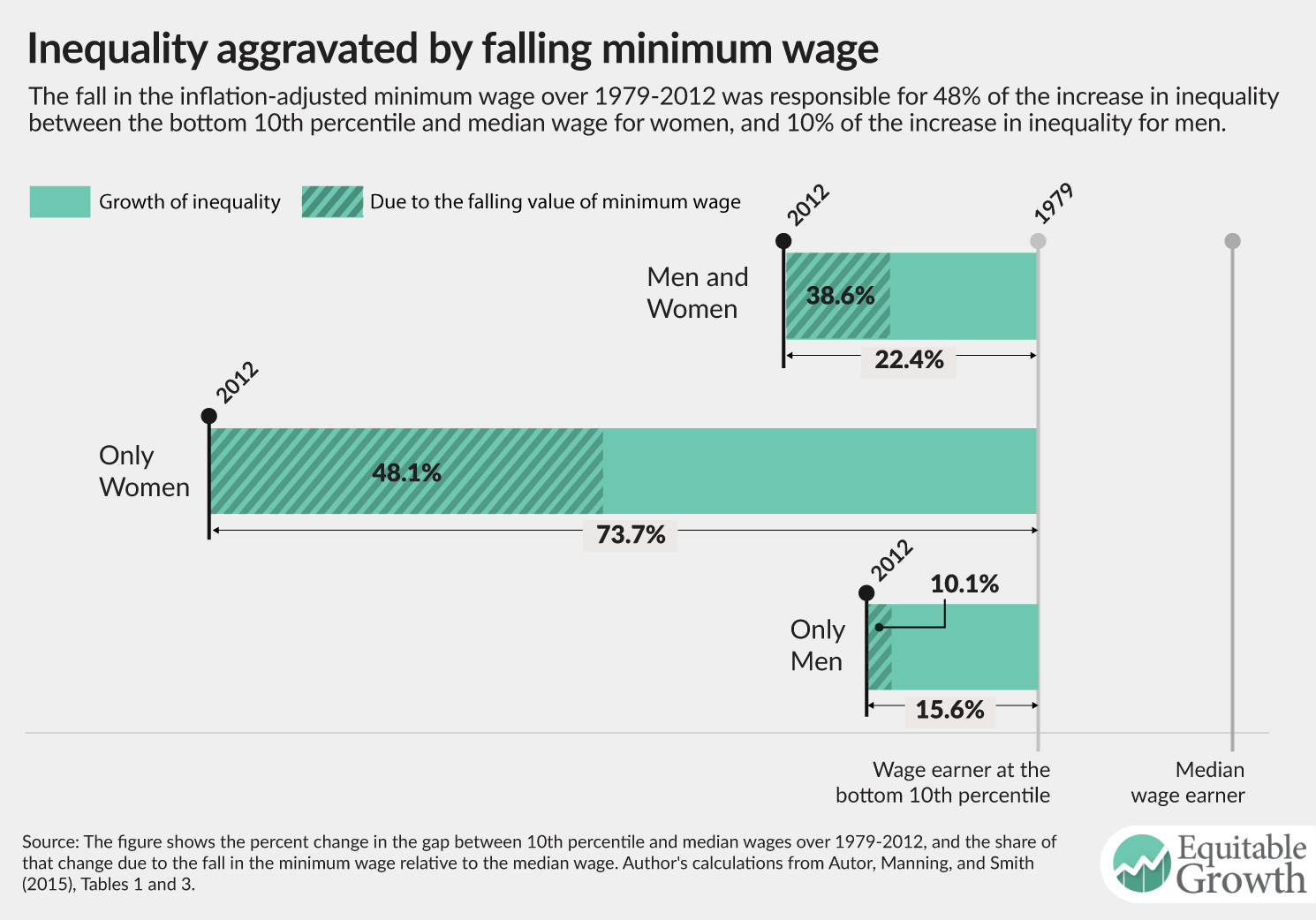

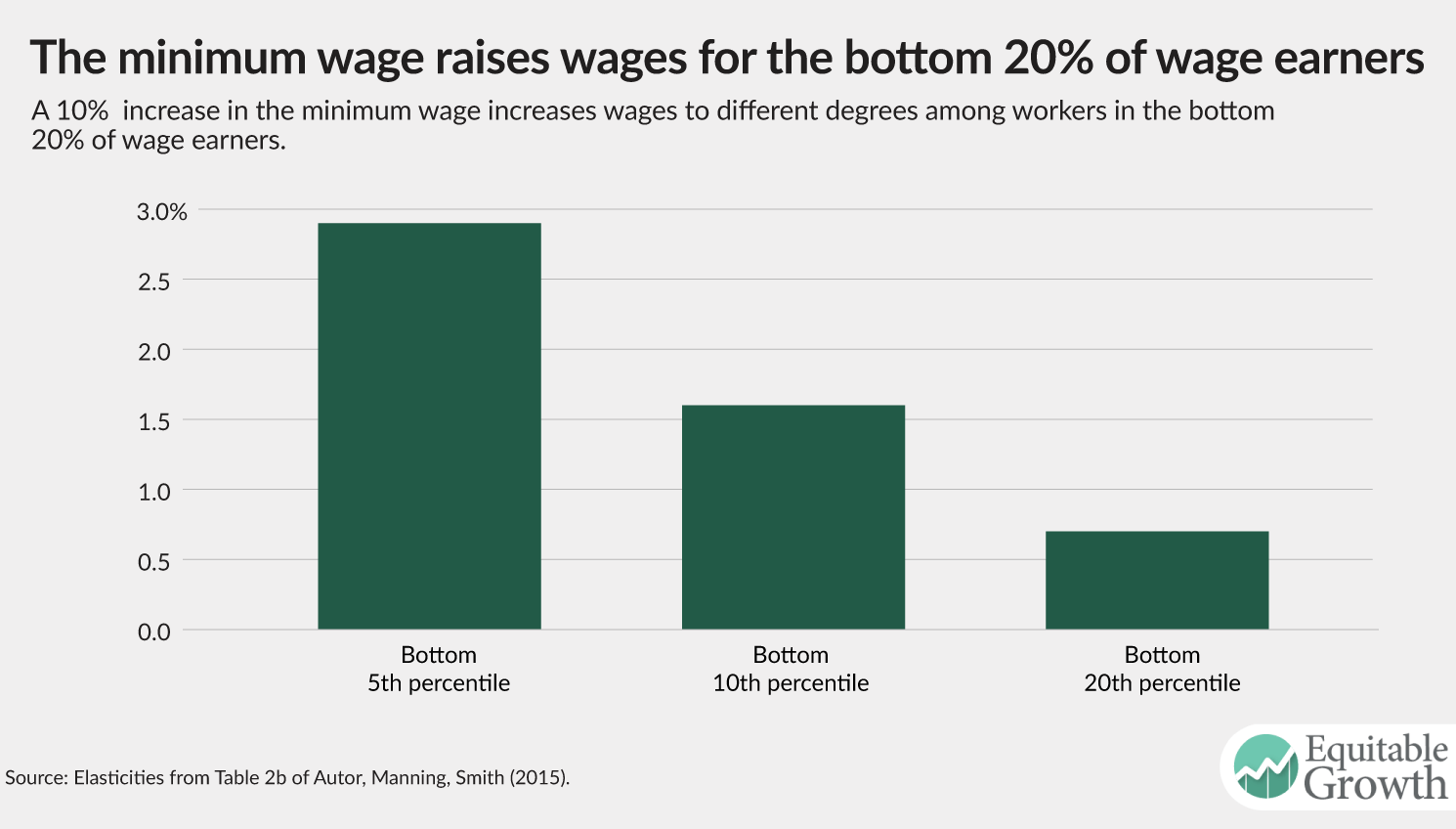

Many U.S. households rely on the incomes of women, especially those headed by single mothers. A recent study by economists David Autor of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (and a member of Equitable Growth’s Research Advisory Board), Alan Manning of the London School of Economics, and Christopher Smith of the Federal Reserve Board examines all state and federal minimum wage increases from 1979 through 2012, and measures the effect of the raises at each point of the wage distribution.2 One key piece of their findings is that because women are generally paid less than men—and therefore fall closer to the bottom of the wage spectrum—the minimum wage has larger effects on female wage inequality. For wage inequality among women, Autor, Manning, and Smith find that the minimum wage had particularly strong consequences. Between 1979 and 2012, the declining minimum wage was responsible for 48 percent of the increase in female wage inequality between the bottom and middle of the wage distribution. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

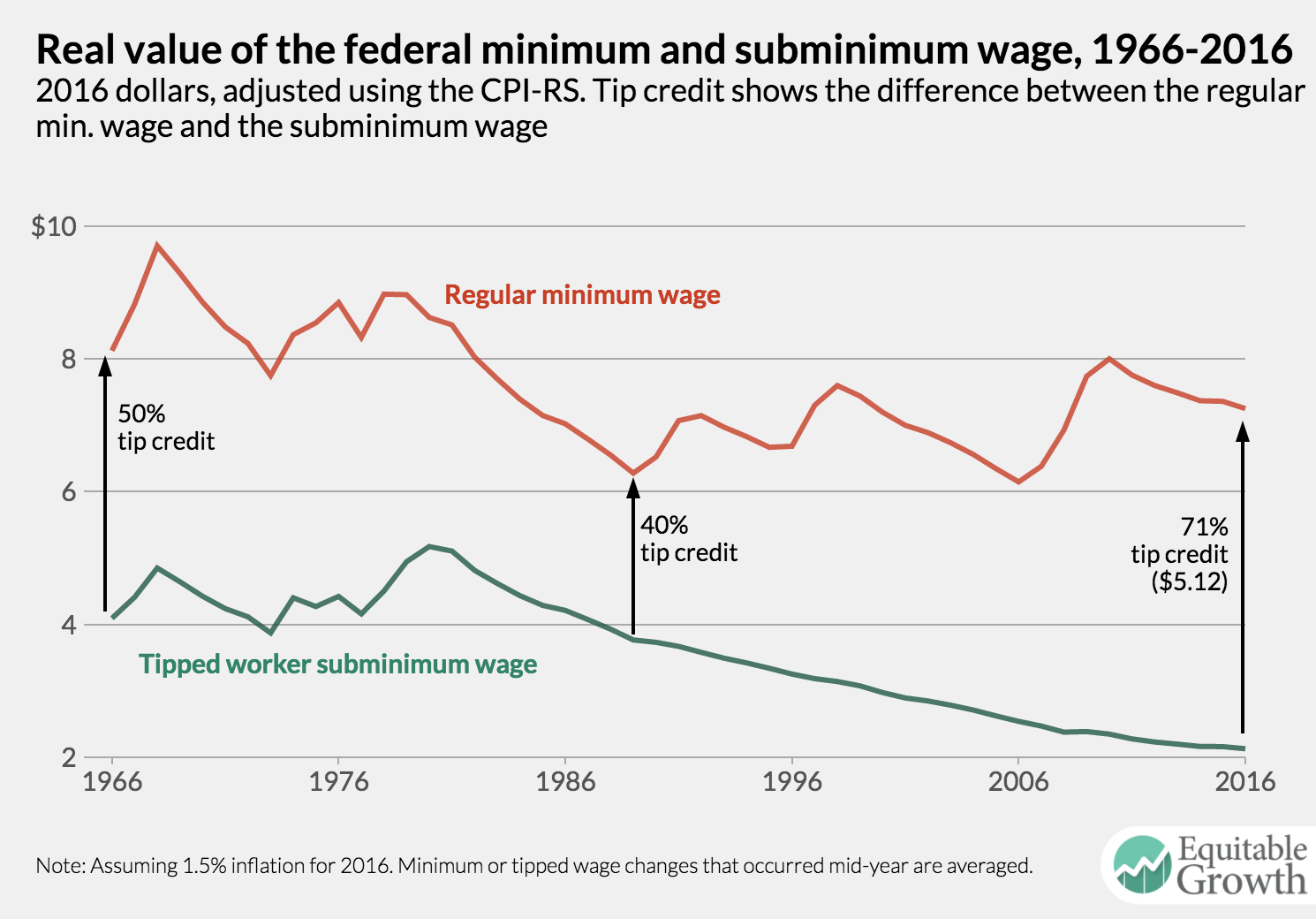

Women are hit particularly hard by anomalies in pay in industries where tipped pay is prevalent such as the restaurant industry. These industries boast many working mothers. Sylvia A. Allegretto, an economist and co-chair of the Center on Wage and Employment Dynamics at the Institute for Research on Labor and Employment at the University of California, Berkeley, wrote an essay for Equitable Growth about the vagaries of the minimum wage for tipped employees.3 In it, she shows that tipped workers are overwhelming female who typically earn low wages. They also have few workplace benefits, live disproportionately in poverty, and experience high rates of sexual harassment. One overall finding about the difference in the regular minimum wage and the lower tipped minimum wage illustrates the problem at hand. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

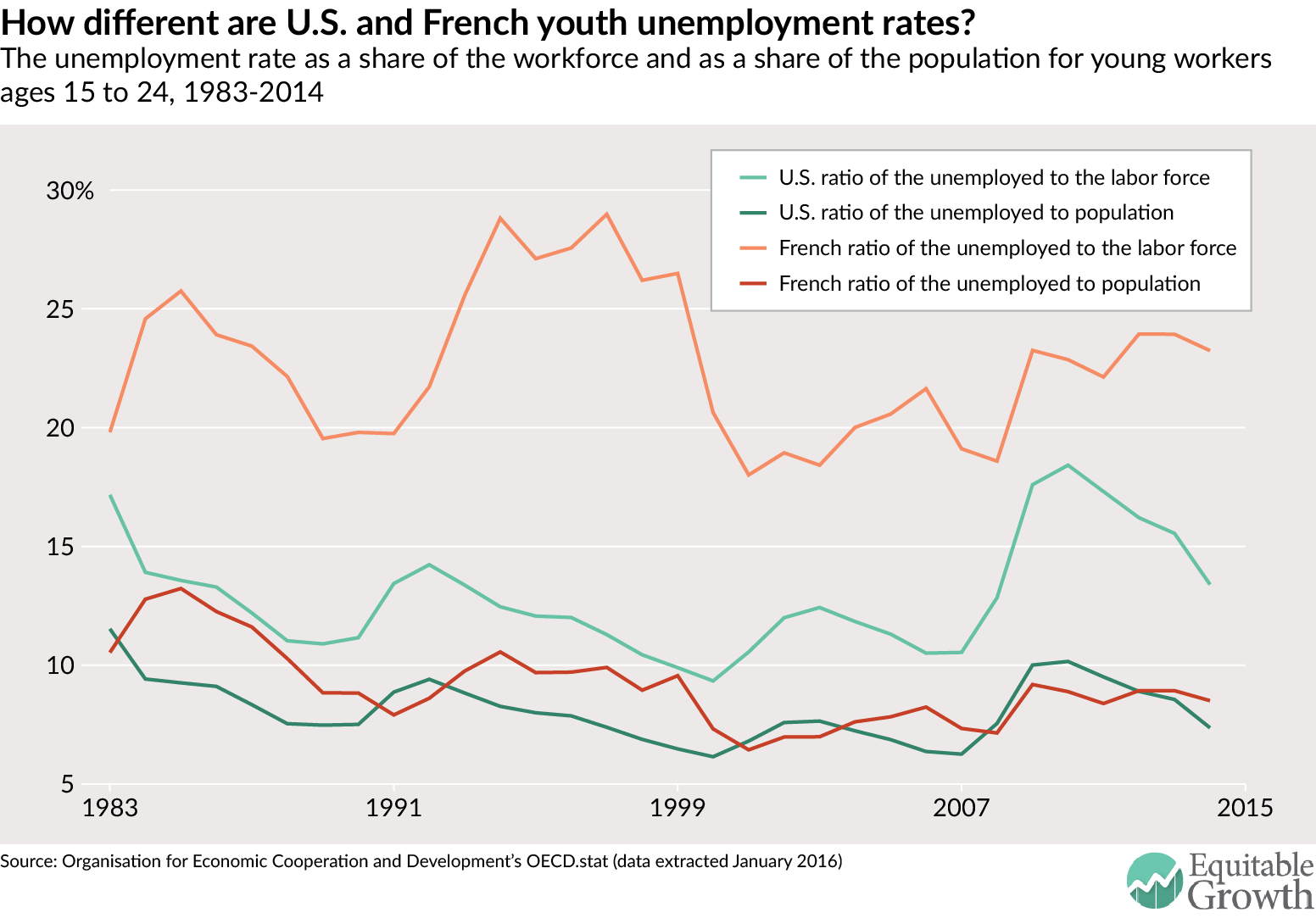

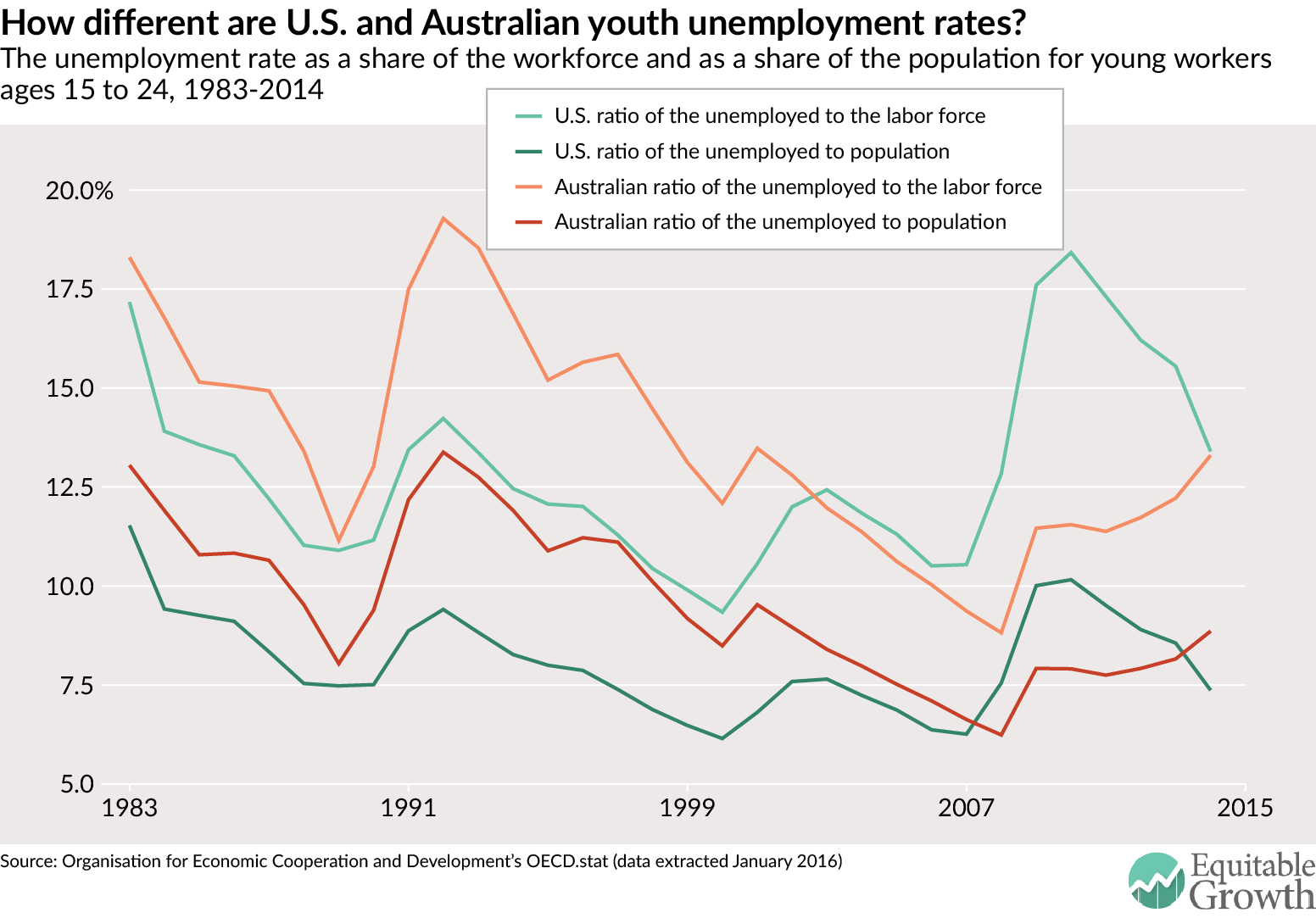

Former Equitable Growth economist Ben Zipperer trained his eye on the impact of the minimum wage on youth employment. In a working paper, he and his co-authors examine one group of low-wage workers—teenagers—whose hourly wages are significantly raised by minimum-wage increases.6 They note that a common objection to raising minimum wages is that doing so will reduce the employment opportunities of low-skilled workers such as teenagers. They show, however, that some studies find negative effects of the minimum wage on teen employment because they fail to control for other economic factors that independently reduced employment around the time of a minimum-wage increase. After controlling for these factors, they demonstrate that the large negative effect on teen employment disappears.

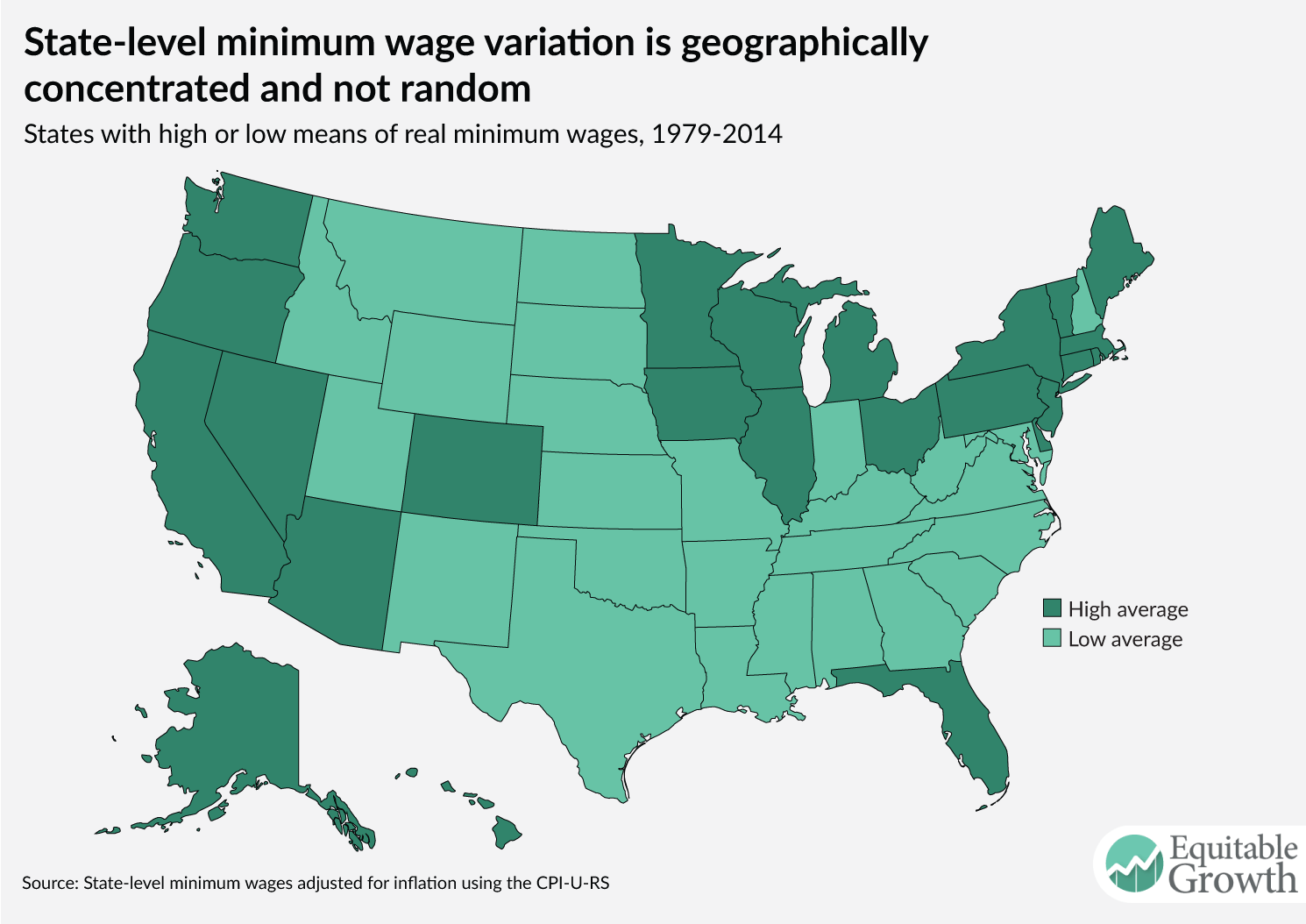

Zipperer and his co-authors note that economists have developed a large body of research comparing the labor-market outcomes in states that raise their minimum wage versus those that don’t. Yet a naive comparison of these two groups of states can lead to misleading conclusions because the variation of state-level minimum-wage policies is not random (which is ideal for assessing the impact of government policies) and is instead geographically concentrated. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

Zipperer and his co-authors show that this map divides states into two groups: states with high average minimum wages and states with low average minimum wages during the 1979–2014 period. States that have high minimum wages were more likely to have been raising their respective wage floors above the federal floor. States with low minimum wages typically followed federal policy. This difference is clearly region-specific.

This clustering of minimum-wage policies within regions of the country is an obstacle for credible research on the minimum wage because comparing the employment of minimum-wage raising and nonraising states effectively compares regions such as the Northeast versus the South. Employment patterns differ in these regions because of a host of economic and political reasons not affected by the minimum wage. High minimum-wage states, for example, also boast higher unionization rates and experienced smaller declines in unionization over the past three decades.

Zipperer in 2015 also did an analysis of how raising the minimum wage ripples through the workforce.7 In it, he says that “although the minimum wage enhances the bargaining power of many low-wage workers, an increased minimum wage’s effectiveness in doing so dissipates as it spreads across the wage spectrum, essentially disappearing for middle-class wage earners.” This ripple effect, he says, “has important implications for wage inequality among workers in the United States.” (See Figure 5.)

Figure 5

How policymakers should think about unemployment and the minimum wage

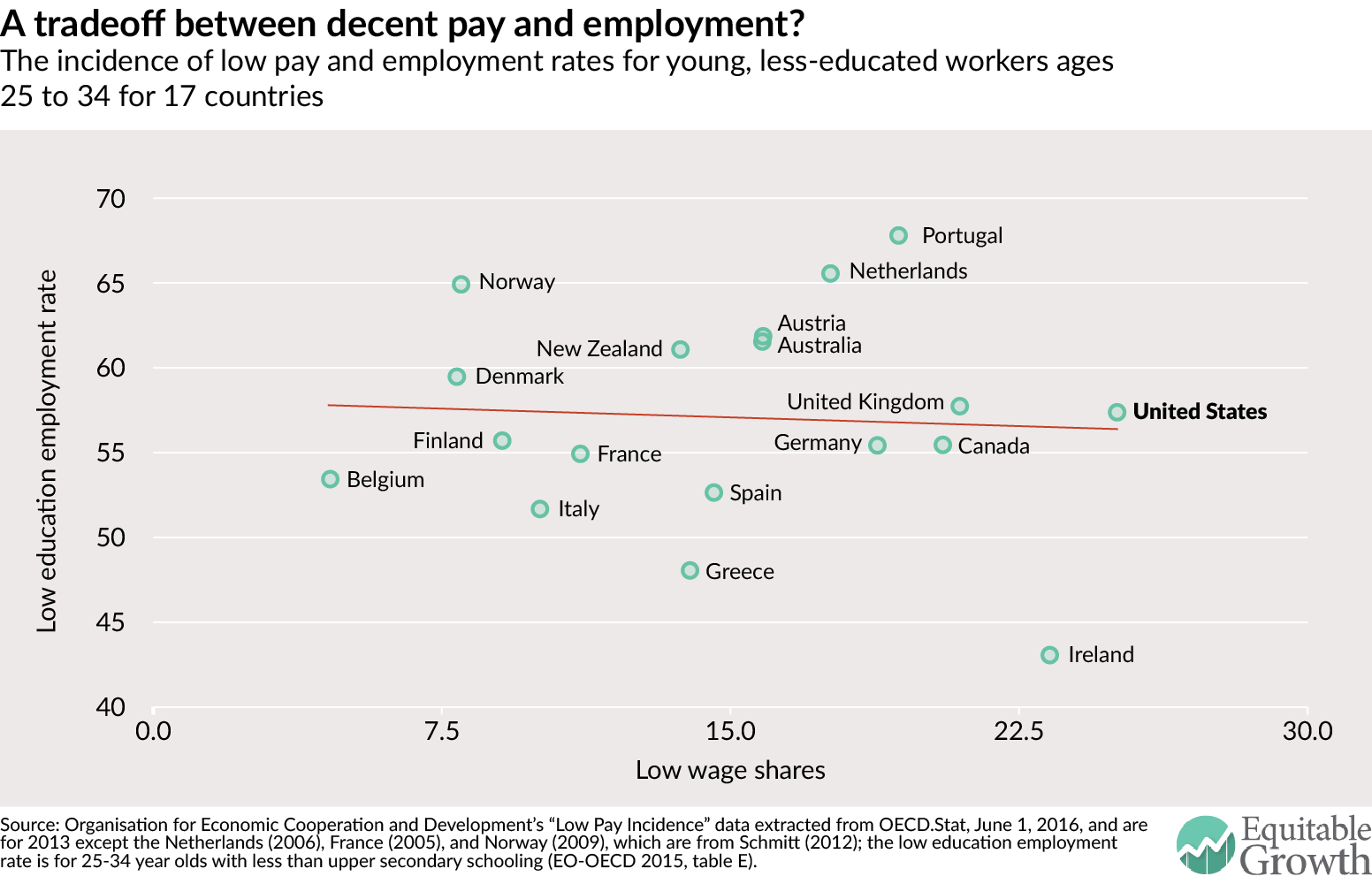

Policymakers need to ask whether the ongoing debate about raising the minimum wage and any resulting job losses is misplaced. David Howell, a professor of economics and public policy and director of the doctoral program in public and urban policy at The New School, argues persuasively that the stalemated academic debate about the minimum wage and any job losses whatsoever ignores the net benefits of raising the minimum wage.8 Howell, an Equitable Growth 2014 academic grantee, notes that “when the criterion for raising the minimum wage is concerned only with the cost side of an increase, the costs of some predicted job losses are all that matters.” But his research, and that of others he points to in his working paper for Equitable Growth, highlights that “there are obviously benefits to raising the legal wage floor that should be counted and compared to the costs.”9

Howell points out that workers receiving wage increases as a result of a rise in the minimum wage benefit directly either because they are earning between the old minimum wage and the new one or because they earn a bit above the new minimum wage since employers increase wages to maintain wage differentials among workers by skill or seniority. The benefits are also evident for taxpayers, he says, because a much higher minimum wage means there is less need for means-tested government programs such as the Earned Income Tax Credit and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program for working families.

“If we really care about maximizing employment opportunities, then we should not hold a decent minimum wage hostage to the no-job-loss standard,” says Howell. “Rather, we should put a much higher priority on full-employment fiscal and monetary macroeconomic policy, minor variations of which would have massively greater employment effects than even the highest statutory wage floors that have been proposed.”

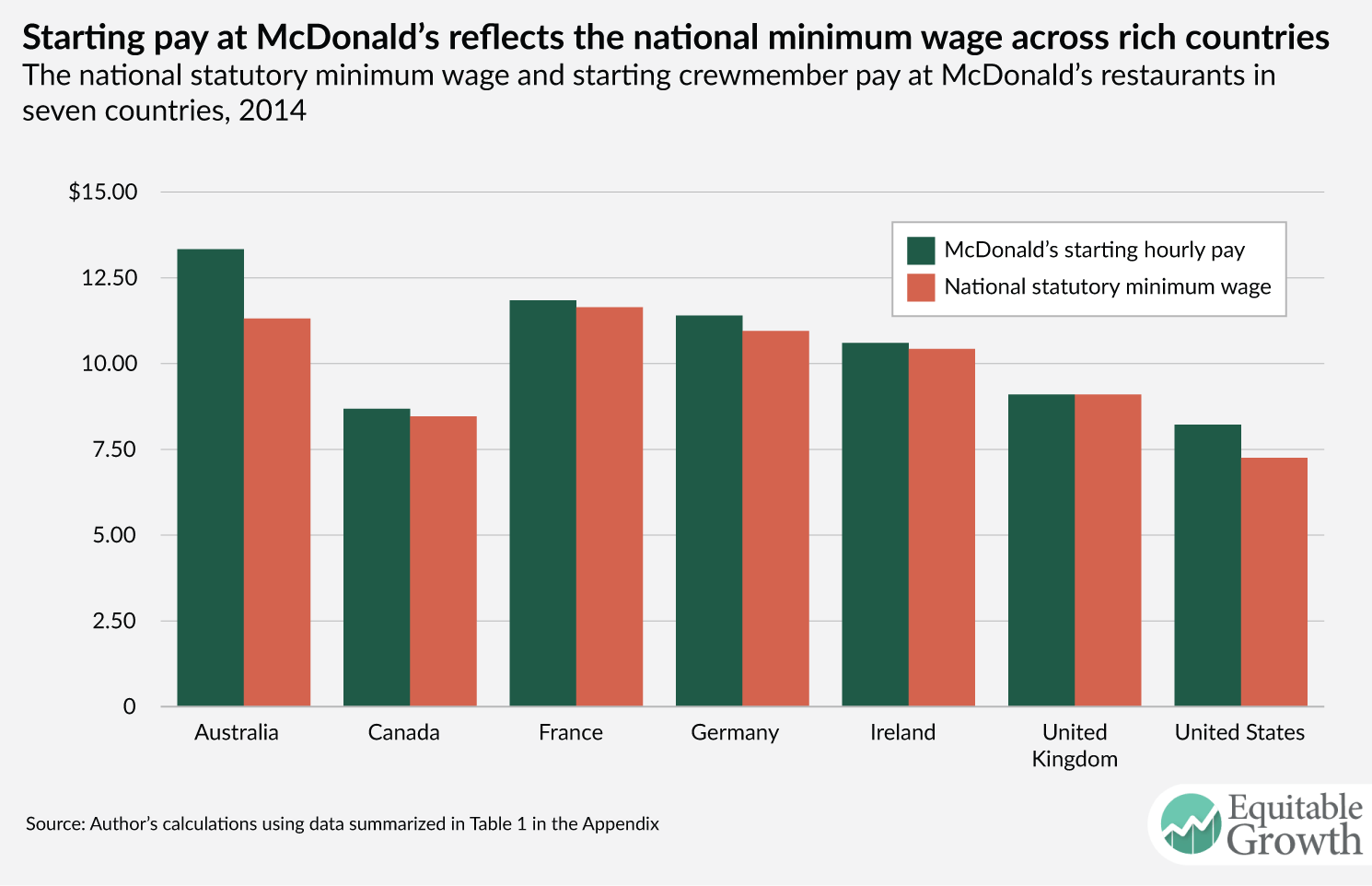

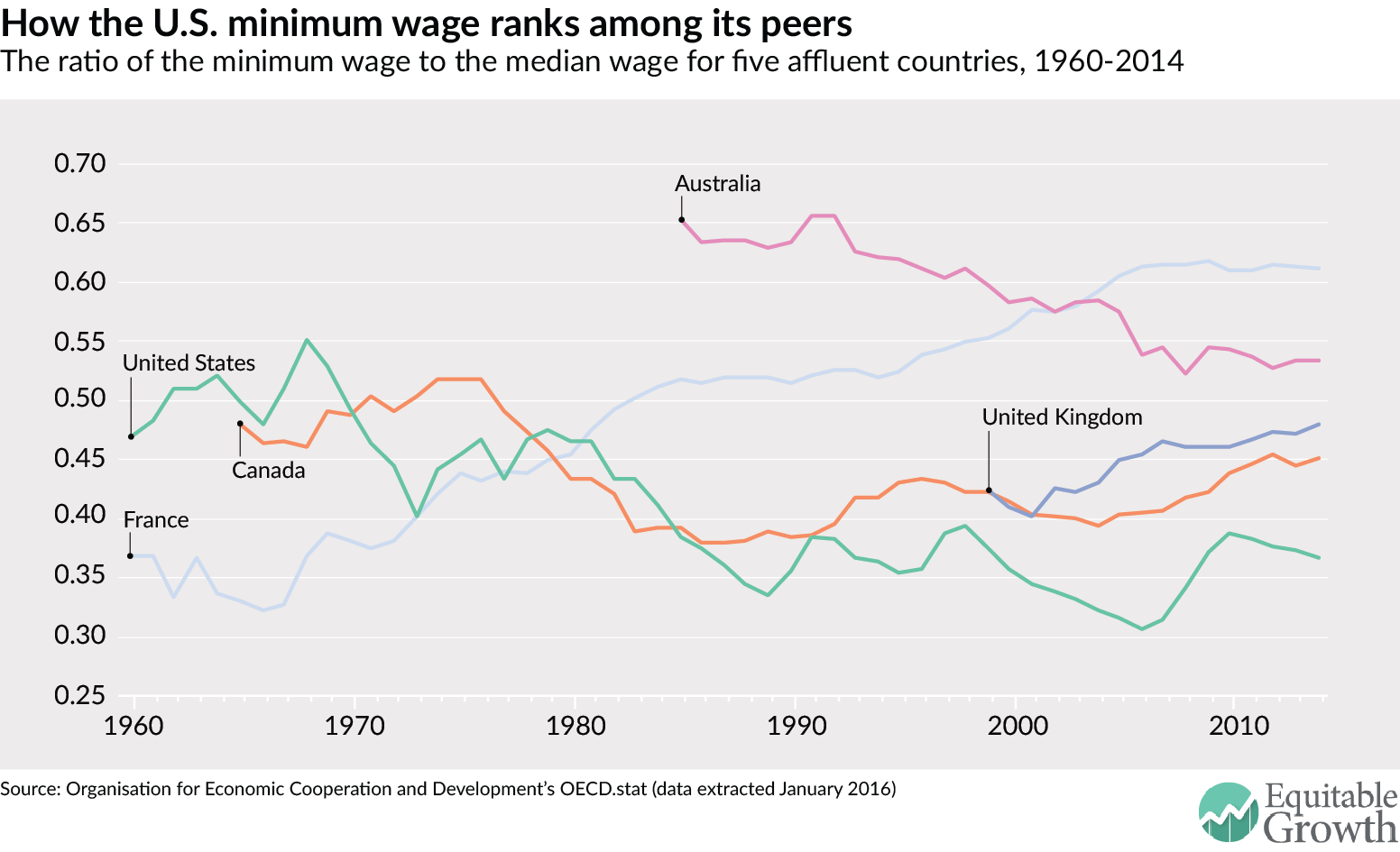

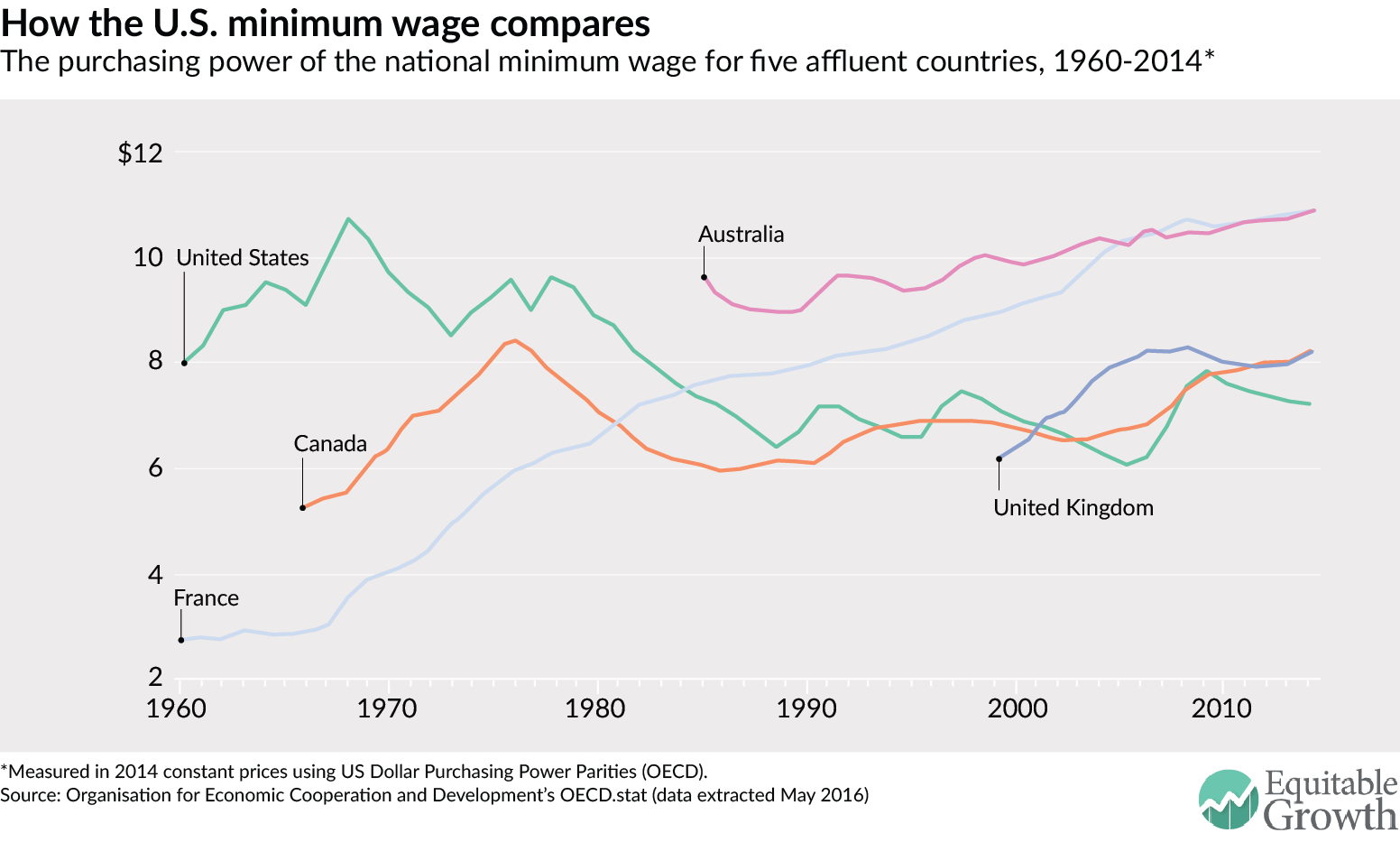

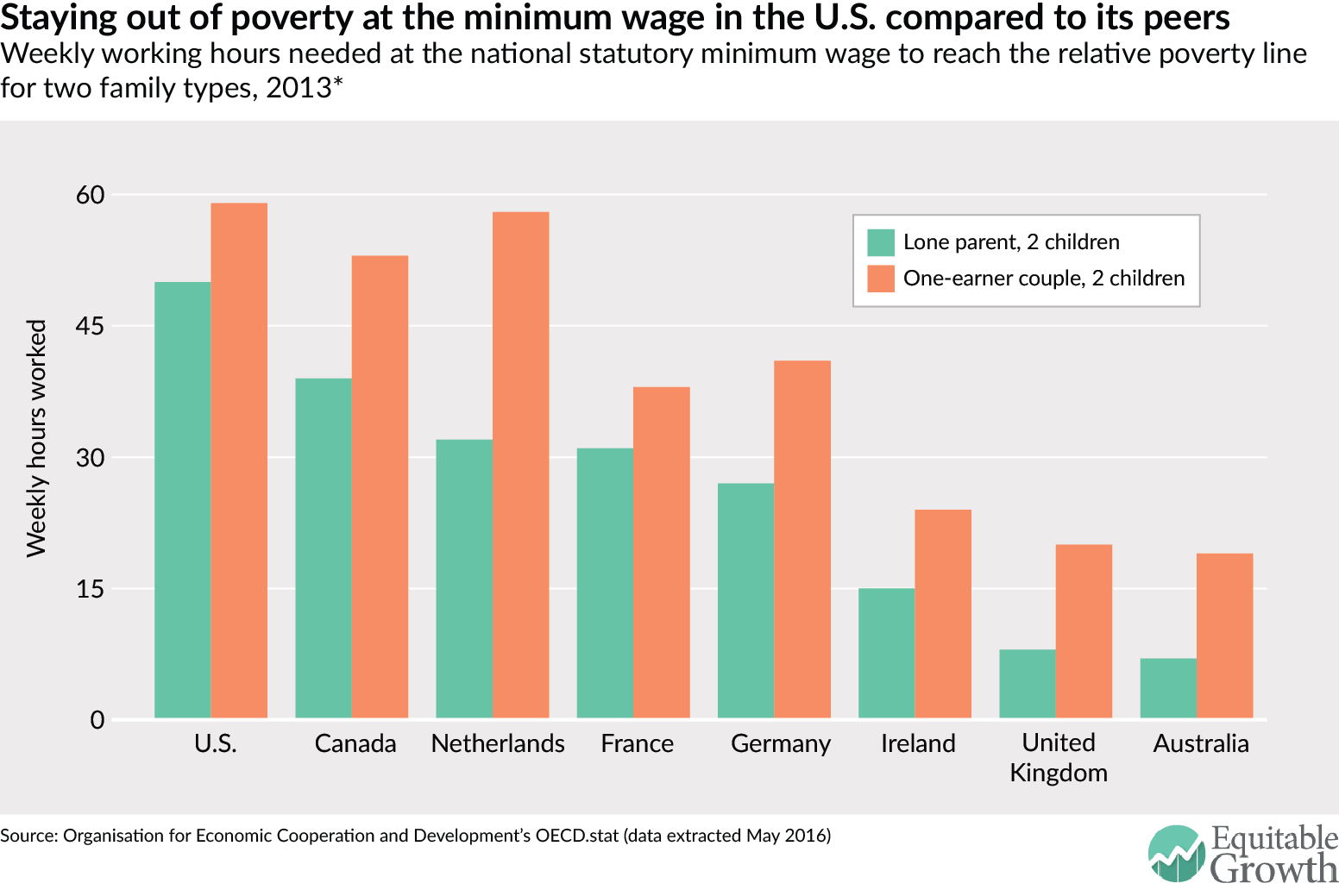

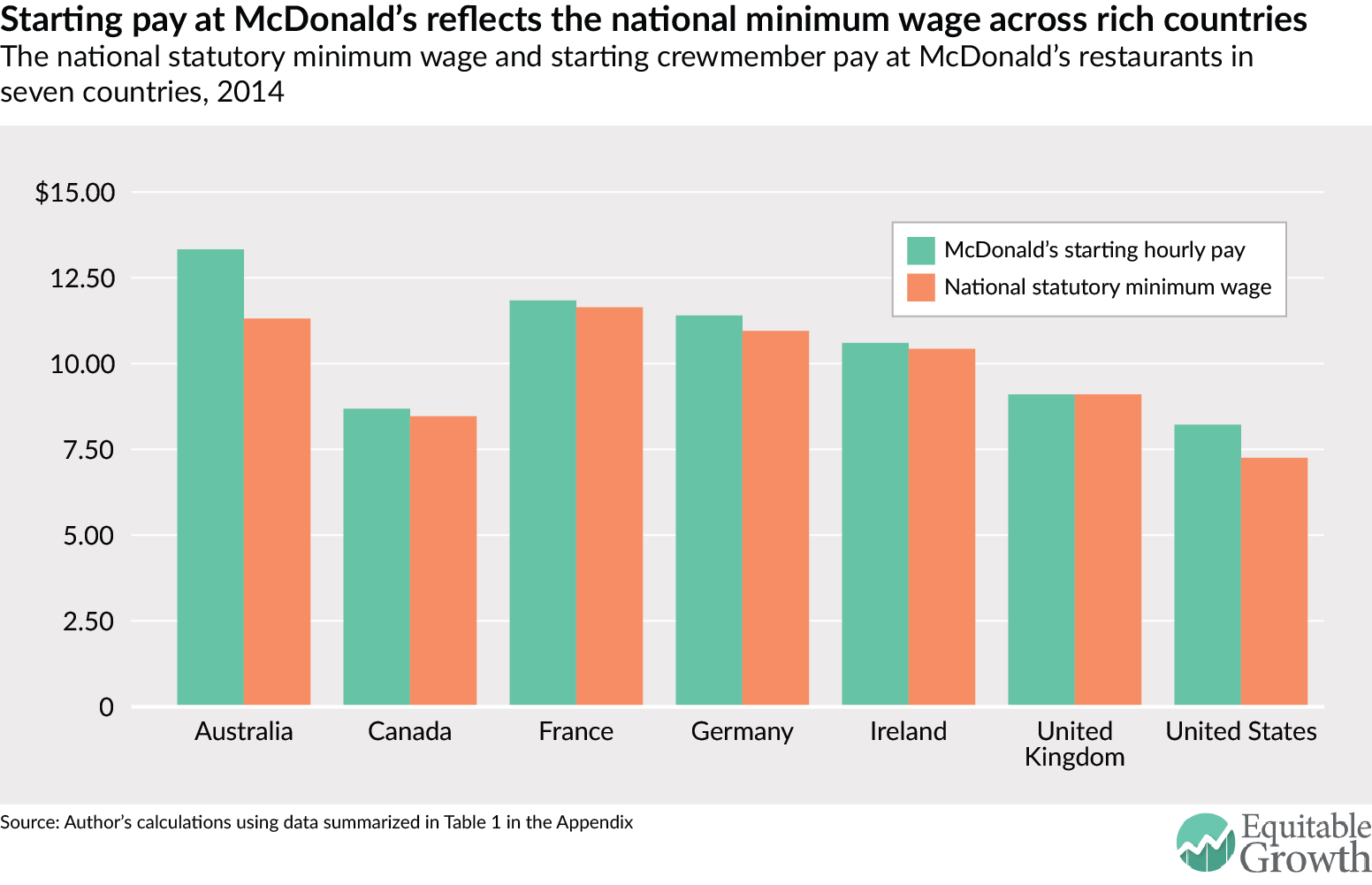

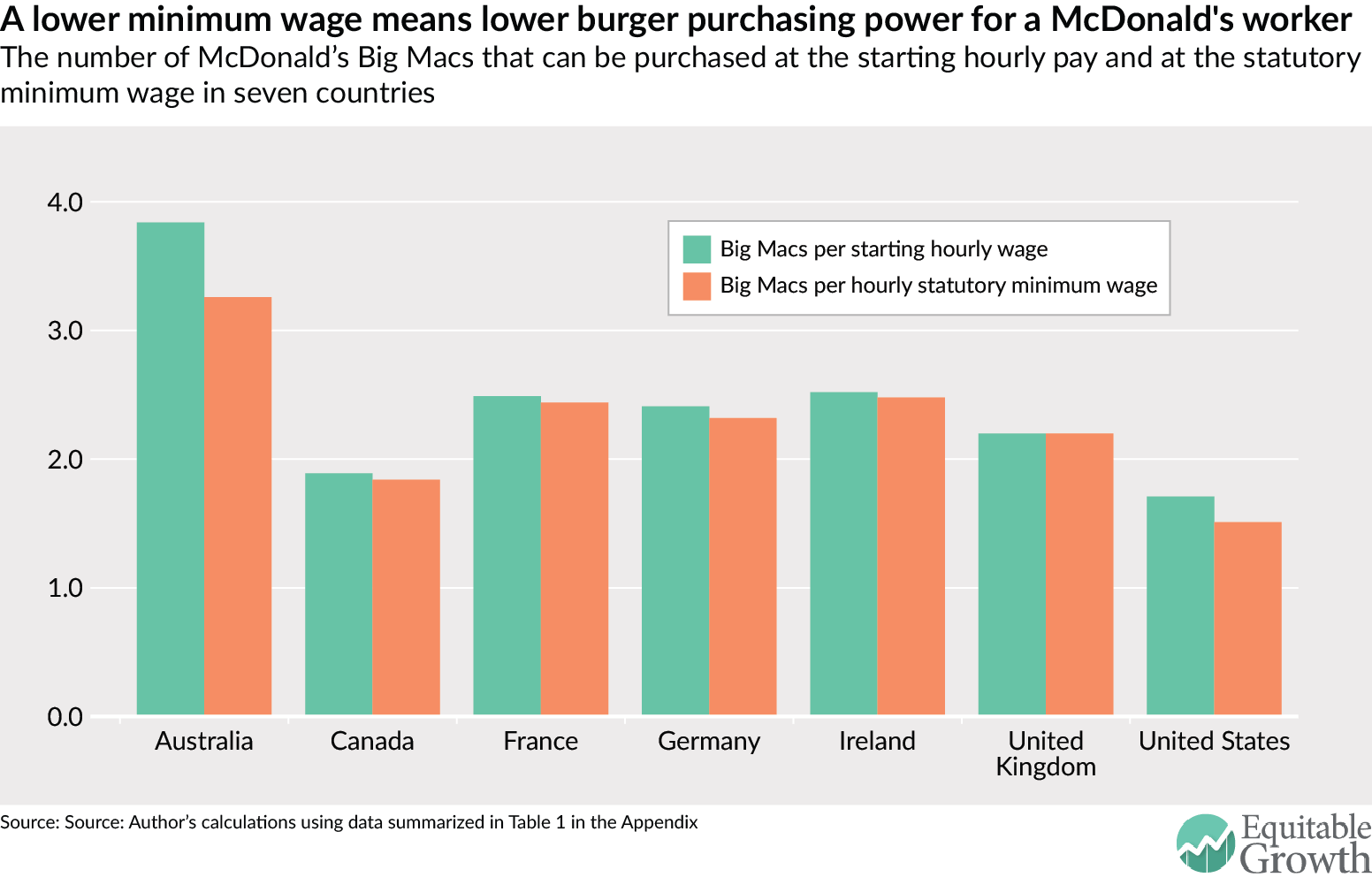

Indeed, Howell argues, “it’s worthwhile to look at the experiences of other advanced economies of the world.” In another analysis for Equitable Growth, he looks at lessons from other rich countries.10 He examines an array of data to show that the United States is at the low end of the minimum-wage level in terms of the median wage and purchasing power, pointing in particular to the purchasing power of a McDonald’s Corp. restaurant employee in select advanced countries. (See Figure 6.)

Figure 6

He concludes this research with the finding that “properly designed and implemented, much higher living standards are possible for working families in the United States by setting the federal minimum wage far above the current level of $7.25 without affecting overall employment opportunities for minimum-wage workers.”

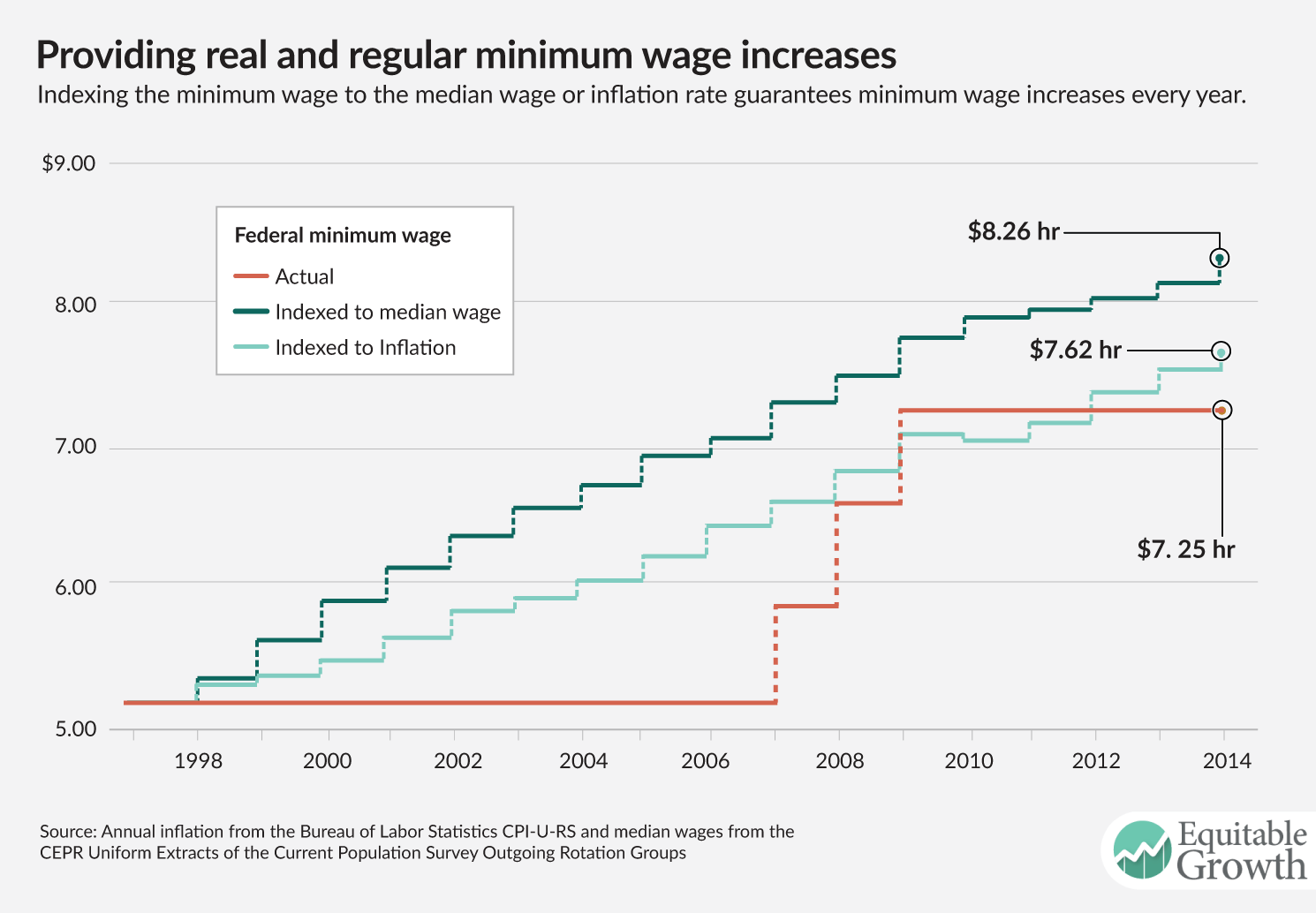

How would indexing the minimum wage affect hourly workers?

Zipperer notes that “economic research on the minimum wage shows that between 1979 and 2012, more than 38 percent of the rise in inequality between the wage paid to the 10th percentile wage (the bottom 10 percent of U.S. workers earn this wage or less) and the median wage is due to the minimum wage failing to keep up with the median wage.”11 By indexing the minimum wage to the median wage, he argues that policymakers would “help prevent widening disparities between those at the bottom and the middle of the wage distribution.”

Importantly, wage indexing allows the minimum wage to rise in ways that the labor market can easily accommodate. Indexing the minimum wage to the general wage level means that roughly the same proportion of workers will earn the minimum wage year after year when the minimum wage rises, says Zipperer. As long as underlying wage inequality does not change too much, fixing the distance between the minimum and median wage will keep constant the share of workers earning at or near the minimum wage.

Because a regularly indexed minimum-wage increase will not substantially alter the share of workers earning the minimum wage, employers will more easily adjust to these indexed increases than they would to the irregular and larger increases typical of the current federal procedure and many of the state and local procedures, Zipperer says. Indexing to the median wage would require employers to raise wages for roughly the same proportion of their employees each year, whereas failing to index typically results in employers being required to raise wages for a much larger share of their workforces on less predictable basis. Here’s how indexing the minimum wage to the median wage—or alternatively to the rate of inflation—would guarantee minimum-wage increases every year. (See Figure 7.)

Figure 7

Conclusion

In testimony by Equitable Growth Executive Director and Chief Economist Heather Boushey before the U.S. Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions on “From Poverty to Opportunity: How A Fair Minimum Wage will Help Families Succeed,” Boushey pointed out the three overarching benefits of raising the minimum wage:12

- It would reduce poverty. According to various economic estimates, raising the minimum wage would lift millions of working families out of poverty.

- It would help family breadwinners support their children. The typical minimum-wage earner brings in half of their family’s income. Congress should also take care to make sure that other benefits for low-wage workers provide a full package for low-wage workers and their families, as families will also need help with access to affordable and quality health care, childcare, and housing, even at a higher minimum wage.

- It would deliver positive economic effects above and beyond lowering the poverty rate. Economic research points to the conclusion that a higher minimum wage does not cause greater unemployment, boosts productivity, and addresses the growing problem of rising income inequality.

Boushey concluded her testimony by noting that “the minimum wage is not a silver bullet in the fight against poverty [yet] any effort to reduce poverty and increase economic mobility at the bottom rungs of the income ladder into the middle class needs to include an increase in the minimum wage.” She said that, “the weight of economic research shows that raising the minimum wage would reduce poverty and work in tandem with other poverty-reducing programs to promote income mobility from the bottom up. In the largest economy on the planet, we need to work harder to reduce poverty. Increasing the minimum wage needs to be part of that effort.”

“Equitable Growth in Conversation” is a recurring series where we talk with economists and other social scientists to help us better understand whether and how economic inequality affects economic growth and stability.

“Equitable Growth in Conversation” is a recurring series where we talk with economists and other social scientists to help us better understand whether and how economic inequality affects economic growth and stability.