Weekend reading: Measuring and achieving a U.S. economy that works for all edition

This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

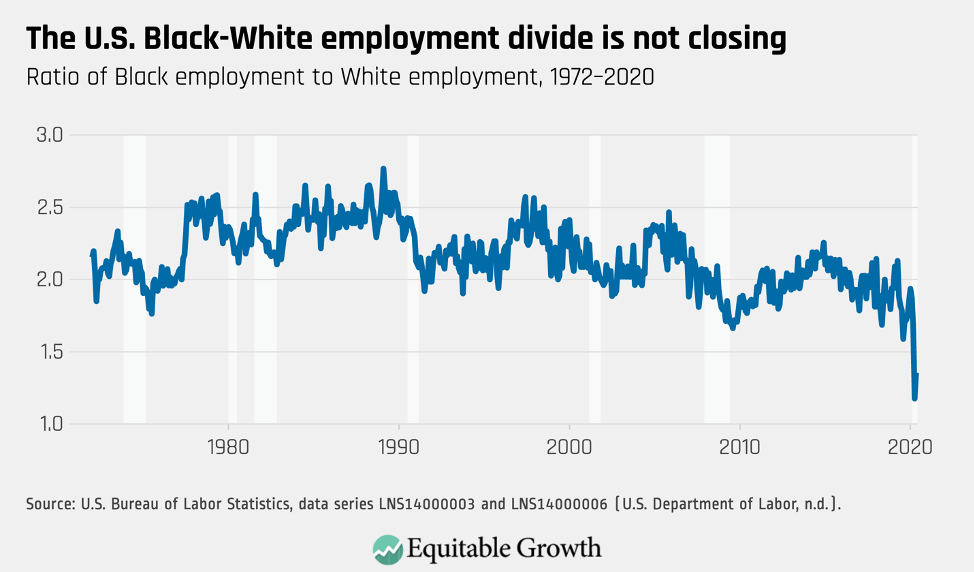

The disproportionate impact of the novel coronavirus and COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus, on communities of color, particularly Black and Latinx communities, alongside the continuing police murders of unarmed Black people without consequences demonstrate more than ever that systemic racism is an ongoing problem in the United States. Equitable Growth has long argued for disaggregating economic data to see who prospers when the economy grows, but Austin Clemens and Michael Garvey explain why doing so would have an additional important result—putting on full display the profound effects of racism across our economy and society, from healthcare to wealth accumulation to the criminal justice system and more. Clemens and Garvey detail how Congress and the executive branch can improve our understanding of economic and social outcomes for communities of color, including improving data collection, performing deeper analyses of racial economic divides, and providing policymakers with a better idea of the needs of marginalized communities in the United States. Specifically, they push for oversampling of communities of color with regard to existing federal surveys and data collection efforts to ensure the data collected is as robust as possible.

Earlier this week, the U.S. Census Bureau released new data on the effects of the coronavirus pandemic on workers and households. Austin Clemens, Raksha Kopparam, and Carmen Sanchez Cumming put together four graphs highlighting important trends in the data—namely, that low-income workers, those with less education, and workers of color are struggling the most amid the coronavirus recession.

Prioritizing stock market growth and using it as the barometer of economic expansion provides an inaccurate look at how the U.S. economy is actually working for workers and their families, writes John Sabelhaus. He explains the hidden costs of only looking at the stock market’s performance but not examining why it has gone up and the policies that increase stock prices at the expense of other things, such as adequate wages or Medicare and Social Security funding. He dives into what moves the stock market up and down, and the government’s role in these booms and busts, to show why stock-market-first economists are wrong to focus on policies that generate stock-price growth rather than a stronger economy for all. Sabelhaus then turns to recommendations for how policymakers should act to spur broadly shared economic growth, including investing in our workforce, infrastructure, innovation, and technology, and, importantly, ignoring the oft-told idea that making wealthy people wealthier will produce trickle-down effects for the rest of us (it doesn’t). Stock-market-first approaches have deepened wealth inequality in the United States, he writes, and those who benefit from a booming stock market are not the same people who are sacrificing so much, particularly during the coronavirus recession.

Policy decisions made over the past half-century weakened the U.S. economy and restricted growth, making the nation more vulnerable to crises such as those we are currently experiencing. We need new policies that support equitable economic growth across the income spectrum in order to truly recover from the coronavirus recession, writes Heather Boushey in an op-ed for USA Today. Lawmakers must enact policies, including paid sick leave, affordable child care and universal pre-Kindergarten, a livable minimum wage, expanded Unemployment Insurance, and small business support systems, Boushey continues—and policymakers must ensure these benefits are triggered on and off automatically. Without automatic stabilizers, economic aid to hard-hit populations in future recessions could be hamstrung by politics, much like the next round of coronavirus relief aid, which is currently stalled in Congress.

Competition among big technology firms is a hot topic, with rumors that Facebook Inc. and Alphabet Inc.’s Google unit may soon face monopolization cases against them. The previous major monopolization case was filed in 1998, against Microsoft, but much has changed since then. Michael Kades and Fiona Scott Morton propose that instead of questioning whether monopolization is occurring, we look at remedies for such violations of antitrust laws. In a recent working paper and accompanying Competitive Edge post, they design a remedy for addressing monopolization by a social media network based on five principles: the network effects of social networks, the entry barriers these network effects create, interoperability, the legal and technical challenges of implementing interoperability, and the role of the Federal Trade Commission’s rulemaking authority in drafting interoperability orders. They then explain each of these five areas and their relevance to designing a remedy to address monopoly violations by social media networks.

Links from around the web

A new study by Citigroup Inc. shows that the U.S. economy lost $16 trillion as a result of discrimination against African Americans since 2000. This is a significant amount, writes Adedayo Akala for NPR, especially when you consider that U.S. Gross Domestic Product totaled $19.5 trillion in 2019. The study breaks down the $16 trillion figure in four key divides between Black and White Americans: lost business revenue from discriminatory lending practices for African American entrepreneurs ($13 trillion); lost income from wage discrimination ($2.7 trillion); lost wealth accumulation thanks to housing discrimination ($218 billion); and lifetime income lost from discrimination in access to higher education opportunities ($90 billion). And that’s not all, Akala reports. The study’s authors also estimate a $5 trillion price tag over the next 5 years for not acting immediately to eliminate racial discrimination, before providing several recommendations for how policymakers can reverse these racial divides.

At the start of the coronavirus recession, the Federal Reserve jumped into action to stabilize the U.S. financial system, which was going haywire as a result of the uncertainty surrounding the pandemic. With stock markets back to pre-pandemic levels, it appears the Fed’s quick action worked, writes Neil Irwin for The New York Times’ The Upshot—perhaps too well. The success of these efforts may have removed the urgency for lawmakers to pass legislation that would extend relief aid to average Americans. This mentality of Wall Street over Main Street means a difficult economic reality today for many workers—especially low-income, less-educated, Black, and Latinx workers, who, as the data show, are being hardest hit by the recession—and small businesses, which are struggling even as large corporations experience record profits. Similar actions focused on rescuing financial systems rather than individuals were taken during the Great Recession of 2007–2009, Irwin writes, which led to a recovery so sluggish that many families were only just beginning to get back on their feet when the virus took hold earlier this year.

The Unemployment Insurance system in the United States is broken, writes Vox’s Emily Stewart. But it doesn’t have to be. Telling the story of one working mother in California, Stewart looks at how workers have been harmed by the UI system’s shortcomings and complexities during the coronavirus recession as well as before the onset of the pandemic. Stewart then examines the ways policymakers can improve how unemployment benefits are delivered and actions they can take to ensure that those who need help are able to access it with ease. Reimagining the UI system “would treat the jobless like customers, not criminals, while helping them stay afloat as they find their next gig,” she writes, making it easier to navigate and ensuring more consistent pay regardless of where workers live.

We lost a key figure in the fight for gender equality last week. Over the course of her career, Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg made it possible for women to gain access to credit and wealth building opportunities, to access the same jobs as men and get paid the same when they did, and generally making society, the labor market, and the economy more equitable. The Atlantic’s Joe Pinsker runs through Ginsberg’s legacy and how it brought about changes to areas of daily life that we take for granted nowadays, including gender roles in the household and the labor force. Though the United States has hardly achieved gender equality, Pinsker continues, without a doubt, Ginsberg pushed us closer.

Friday figure

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s “Structural racism and the coronavirus recession highlight why more and better U.S. data need to be widely disaggregated by race and ethnicity” by Austin Clemens and Michael Garvey.