U.S. retail sector’s recession experiences highlight continuing labor market travails

The coronavirus pandemic and the ensuing economic recession has changed the structure of the U.S. labor market. Public health measures require limiting in-person services, and as a result, many industries saw sharp declines in employment in the springtime. Some industries, such as leisure and hospitality, then experienced a second downturn as the pandemic surged in the winter. Other industries that faced structural changes over the long term have seen some of those processes sped up.

In this column, we examine how the retail industry has been affected by the coronavirus recession, how this has been influenced by preexisting trends in the industry, and what this means for worker well-being of those employed across different types of retail jobs.

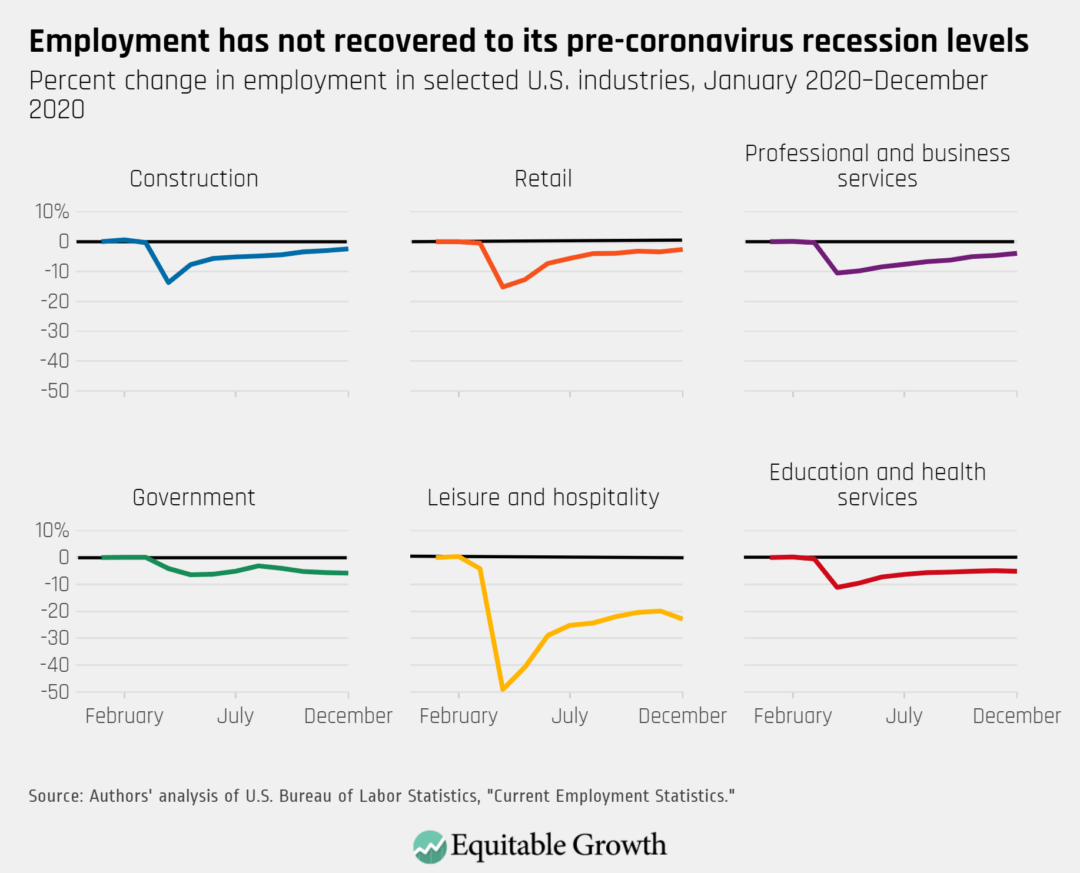

The latest Employment Situation Summary, released on January 8 by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, also known as the Jobs Report, shows that between mid-November and mid-December of 2020, the U.S. economy lost 140,000 nonfarm payroll jobs. Among the major U.S. industries, employment declines were especially large for the leisure and hospitality sector, which lost nearly half a million jobs. Government lost 20,000 jobs, making December the fourth consecutive month in which public-sector employment declined. But other industries saw important gains. The professional and business services and retail trade sectors added 161,000 and 121,000 jobs, respectively. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

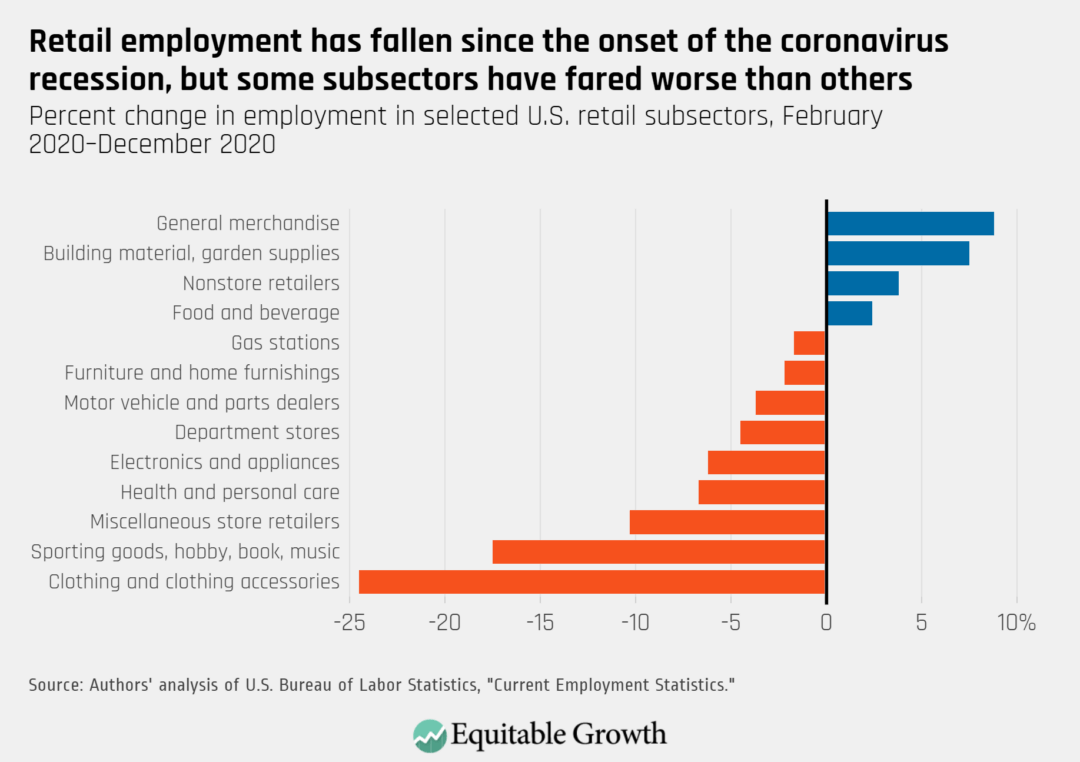

Despite these gains, in December 2020, the retail sector employed 410,000 fewer workers than in February of that year. Moreover, the coronavirus recession hit some parts of the industry much harder than others. For instance, the number of jobs in sports, hobby, book, and music stores shrunk more than 17 percent between February 2020 and December 2020. Almost 1 in 4 clothing store jobs have been lost since the onset of the crisis. At the same time, garden supply stores, nonstore retailers, and general merchandise stores—which include warehouse clubs and supercenters—have actually grown amid the economic downturn. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

This uneven effect on retail reflects two important features of the coronavirus recession. First, because the measures needed to contain the dual economic and health crises affected both demand for goods and services and the operations of many retailers, workers employed in nonessential businesses and holding jobs that require face-to-face interactions have generally been more exposed to layoffs. For the frontline retail workers who kept their jobs, going to work became much riskier.

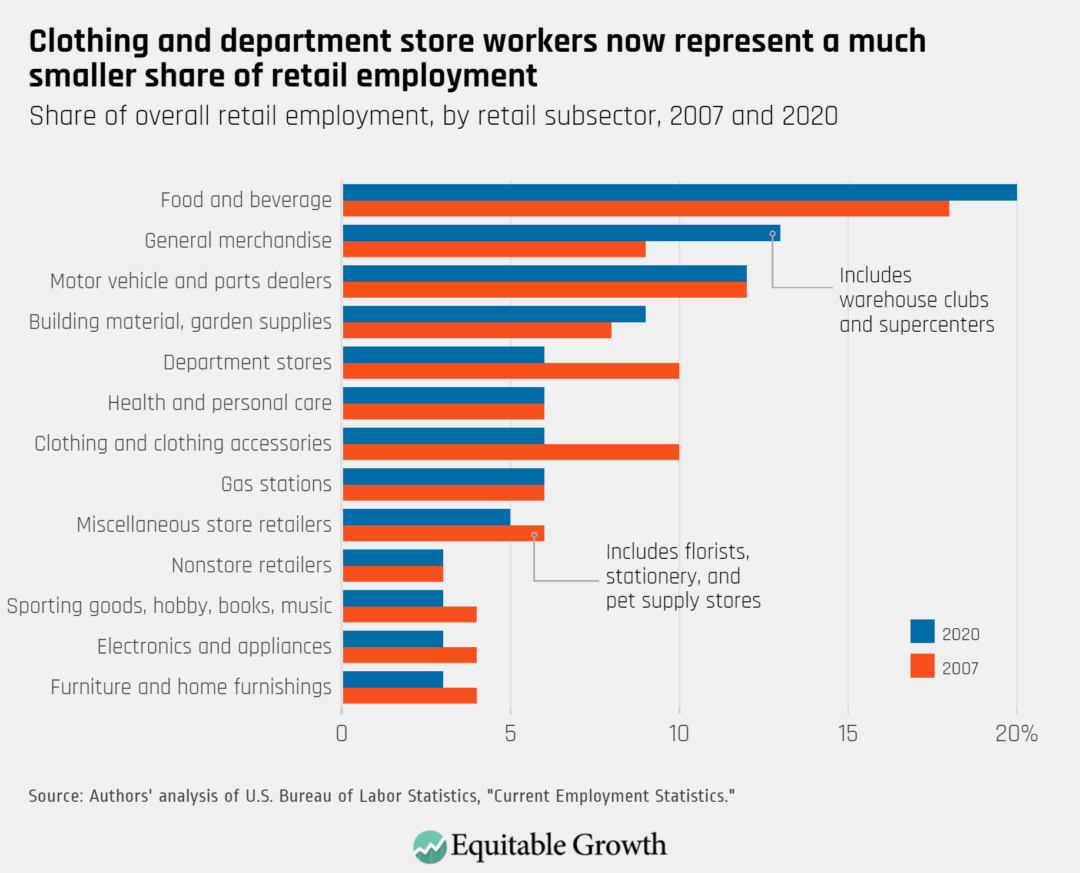

Second, and as with other economic trends, the downturn could be accelerating dynamics that were reshaping the retail sector well before the onset of the recession. Over the past decade, the sector’s somewhat sluggish recovery from the Great Recession of 2007–2009 was marked by the growth of e-commerce and bankruptcies of well-known apparel and department stores that media reports called a “retail apocalypse.” Even though there is evidence that the degree to which the industry is declining is overstated, retail employment fell somewhat since reaching its peak in early 2017, and is not projected to grow in the next decade.

Additionally, the same parts of the industry that are being hardest hit by the current downturn—clothing, sporting goods, and personal care stores, for example—have shrunk relative to the size of the retail sector since at least 2007. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

What does this mean for U.S. retail workers? In the immediate term, continued job losses in the retail sector are hurting some of the most vulnerable workers in the U.S. economy. For instance, 2019 research shows that retail salespersons—a position in which women workers, Black workers, and Latinx workers make up a disproportionately large share of the workforce—represent more than 8 percent of all low-wage U.S. workers, a significantly higher share than any other single occupation. More broadly, the sector pays the second-lowest average wages of any major U.S. industry. Only a small fraction of workers has access to employer-provided benefits. In addition to poor compensation, features of bad-quality jobs, such as unpredictable schedules and high rates of turnover, are rife across the retail industry.

As for longer-term implications, research from the Urban Institute finds that retail jobs are often the first rung in workers’ career ladders, making good jobs in retail an important piece of career advancement and influencing lifetime earnings growth. And while many workers transition out of the retail sector when switching jobs, workers of color in general and Black women in particular are less likely than their White counterparts to exit service and retail occupations. As such, policymakers should prioritize measures that improve labor standards amid the cyclical downward pressures on job quality.

One way to do this is to raise the wage floor. Even though more than one-fifth of retail jobs earn the minimum wage, nearly 30 states increased minimum wages at the beginning of this month. Maintaining minimum wage increases is a critical part of boosting wage growth in the eventual economic recovery. Research from Kevin Rinz and John Voorheis of the U.S. Census Bureau estimates that some of the worst earning losses of the Great Recession would have been partially offset if the federal minimum wage was increased at the magnitude of the increase in Seattle between 2013 and 2016.

In addition to maintaining and increasing job standards, the overall decline in job growth in December and the persistent decline of employment in retail through the coronavirus recession points to the continued need for direct relief to these hard-hit workers. Unemployment insurance systems need to be shored up and more generous unemployment benefits and direct stimulus payments need to be expanded. Research by Ammar Farooq of Uber Technologies Inc. and Adriana Kugler and Umberto Muratori of Georgetown University shows that Unemployment Insurance benefits improve job quality as workers have the time and financial security they need to move into employment opportunities that better match their skills and interests.

Protecting the economic well-being of workers on the bottom rungs of the wages ladder would power a more robust U.S. economic recovery and improve the resiliency of workers in the long-run so that future economic growth would be more broadly shared.