The telling connection between affirmative action litigation, the racial composition of U.S. police forces, and the level of police killings of civilians

The disproportionate killing of innocent and unarmed Black men and women by police forces across the United States continues today despite more than five decades of steadily integrating many of those same police forces with Black male and female officers. The centuries-long legacy of racism informing policing methods across the nation—costing the lives of untold numbers of innocent African American civilians—obviously still lingers.

But can affirmative action litigation intended to increase the presence of Black officers in the ranks of local police departments reduce the number of non-White civilian deaths at the hands of police over time? This is the question we set out to answer in our new working paper, “The Impact of Affirmative Action Litigation on Policy Killings of Civilians.” Our research examines whether the nationwide wave of affirmative action litigation in the wake of the enactment of the Civil Rights Act of 1968 reduced the police killing of non-White civilians.

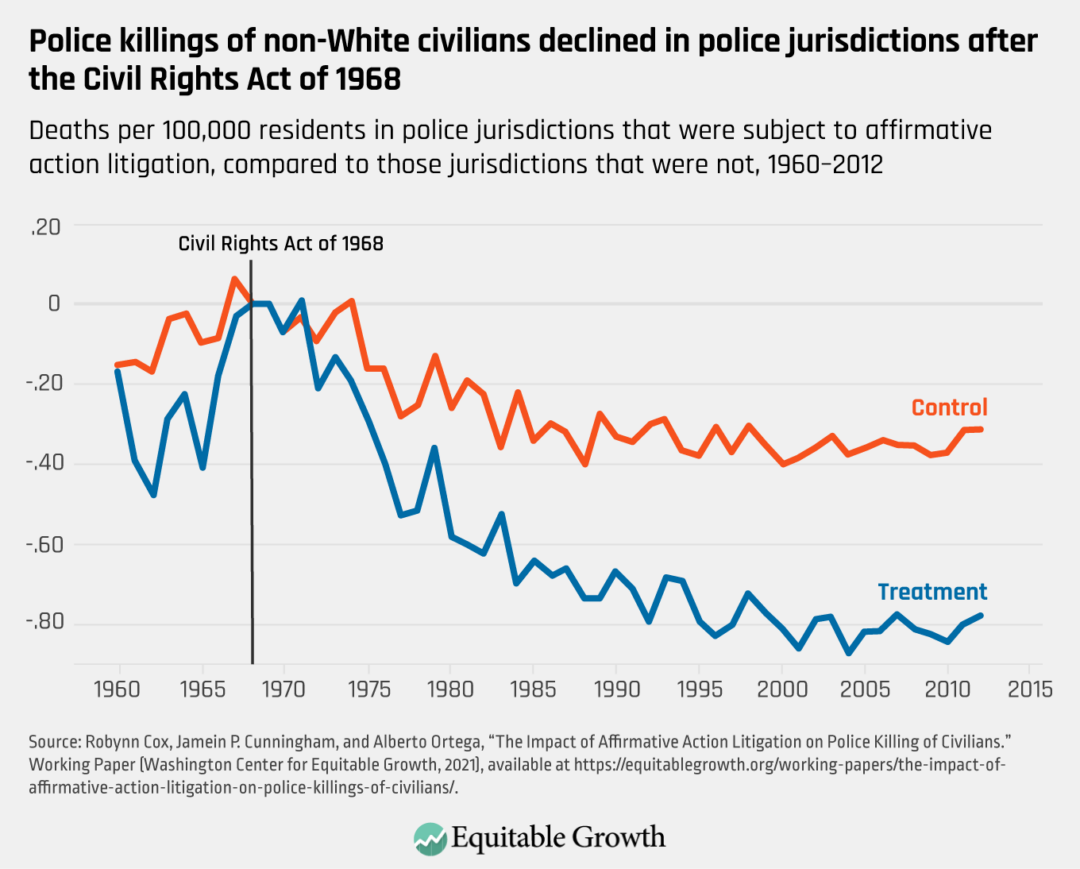

Our findings are telling. Counties across the country that experienced affirmative action litigation saw fewer non-White individuals killed by police. This includes counties where litigation was not successful in leading to an affirmative action mandate. Between 1960 and 2010, we estimate roughly 70 fewer non-White deaths, and police departments facing affirmative action litigation reduced non-White deaths overall by roughly 40 percent. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

In total, we estimate that more than 1,600 deaths of non-White civilians did not occur over the past 60 years due to the success of affirmative action litigation against what were once overwhelmingly White police forces in the United States.

Some caveats accompany our research findings. One is the underreporting of deaths at the hands of the police. We also are unable to identify the outcome of litigated cases. Nonetheless, we go through great lengths to isolate the effects of litigation on police killings of civilians, along with some potential explanations or mechanisms for our findings.

Below, we present the historical backdrop and research methodology that details our study’s context, motivation, and approach.

The historical backdrop to our research

Excessive use of police force against African American civilians has been a critical concern for racial justice and well-being in Black communities. Police violence is a leading cause of death for young Black men, following accidents, suicide, other homicides, cancer, and heart disease. Police violence in Black communities also led to the Black Lives Matter movement and racial reckonings across the nation over the past several years. Concerns about policing and police violence led to President Barack Obama’s creation of the Task Force on 21st Century Policing.

But these trends are not new, and the civil rights protests and reckonings are equally familiar historically. Particularly in the late 1960s, cities experiencing significant excessive use of police force also experienced oftentimes-violent protests—leading to the Kerner Commission of 1968, which recommended (among other things) more racial diversity within U.S. police forces, alongside greater oversight and transparency and more diversity training for police forces.

The passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1968 expanded litigation for civil rights claims, including hiring discrimination, and police forces subject to litigation increased hiring quotas and diversified their police forces. But the recommendations of the Kerner Commission moved these efforts forward in earnest in many police forces and counties across the country.

Our research methodology and our detailed findings

Beginning in 1969, municipal police departments all over the country experienced lawsuits intended to bring about court orders to diversify police forces. We exploit the timing and location of the litigation faced by police departments to estimate the impact of the threat of affirmative action on civilian killings. We used a so-called difference-in-difference event study on pre- and post-treatment counties—social science research parlance for comparing apples to apples before and after something happened in specific places—that faced the threat of affirmative action litigation. We used data on the vital statistics of police killings, county-level data on affirmative action litigation, and county-level demographic data.

We find that following the threat of litigation, the treatment counties experienced a brief increase in the likelihood of non-White civilian deaths in the late 1960s, perhaps due to racial conflict during that time in U.S. history, followed by a long-run decline in non-White deaths through to the end of the past century. A snapshot of the racial diversification of the Chicago Police Department and the decline of non-White civilian deaths is emblematic of our findings across the country. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

But our estimations come with a number of caveats due to data limitations. Other evidence demonstrates a gross underestimation of police killings of non-White civilians, yet independent efforts to collect better data are more recent than our historical period of study. And even though we had access to county-level vital statistics data and police jurisdiction-level litigation data, we were unable to directly estimate the impact of the threat of litigation on civilian deaths within the jurisdictions of a police force since civilian death data are for a larger geographic unit.

Still, we find larger effects when the police jurisdiction under litigation covers a significant portion of the county’s non-White population. What’s more, the threat of litigation may have spillover effects that our research did not encompass. One example of such a spillover effect is changes in police activities in neighboring police jurisdictions. But we find no effect of the threat of litigation on nearby counties, relative to counties farther away, which provides evidence of a more localized effect.

All that said, the data at our disposal and our methodology enable us to conduct a variety of estimations on potential mechanisms behind the decline of non-White civilian killings by police in our treatment counties. We find that the threat of affirmative action did result in increasing diversification of police forces and lower property crime arrest rates for non-White civilians. The latter result may be indicative of a decrease in the frequency of police-civilian contact resulting from litigation.

The diversification of police forces, however, is only a partial solution to the harms caused by racism within U.S. police forces. Other factors, such as a legal system that continues to criminalize, to a greater degree, those living in underrepresented communities, will also influence police interactions within those communities. Above all, though, our research highlights the vital role of federal interventions in addressing police behavior and the use of lethal force in the United States.

—Robynn Cox is an assistant professor at the University of Southern California’s Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work. Jamein Cunningham is an assistant professor at the Jeb E. Brooks School of Public Policy at Cornell University. Alberto Ortega is an assistant professor at the O’Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs at Indiana University.