The importance of anti-discrimination enforcement for a fair and equitable U.S. labor market and broadly shared economic growth

Overview

Almost six decades ago, the U.S. government enacted a series of landmark laws and regulations that advanced equal pay protections, protected against workplace segregation, and made it illegal for employers to discriminate against workers on the basis of sex, race, color, national origin, or religion. In addition, it created what continue to be the two main agencies responsible for the enforcement of federal anti-discrimination efforts—the independent U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and the Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs within the U.S. Department of Labor.

These two agencies are charged with removing barriers to employment opportunities, promoting the creation of fair and equitable jobs ladders, and pushing against workplace segregation—primarily through the enforcement of anti-discrimination protections. Historically, both the new commission and the new agency played key roles in improving the labor market standing of historically marginalized workers, especially between the late 1960s and early 1980s, when affirmative action and federal anti-discrimination laws led to the better representation of women workers and workers of color in both the overall U.S. workforce and in well-paying occupations. These groups of workers were able to access more and better jobs while gender and racial earnings divides narrowed.

Yet even as anti-discrimination laws and U.S. labor market institutions led to important progress toward more fair and equitable labor market outcomes, employment discrimination continues to be a pervasive feature of the U.S. economy today. Insufficient funding and vulnerability to political whims often keep these two federal agencies from protecting workers against unfair treatment at work, and structural power imbalances in the country’s employment relations severely inhibit the effective enforcement of civil rights.

Workplace discrimination harms the workers who experience it, exacerbates structural and longstanding inequities in the U.S. labor market, and holds back economic growth and dynamism. As a result of these continuing practices by employers, millions of workers continue to face discrimination and remain vulnerable to unfair, inequitable, and often illegal workplace practices. Especially at risk are mostly low-income U.S. workers who must deal with employers who flout U.S. labor market laws and regulations, and engage in harassment, taking advantage of structural racism and sexism that limit outside options and economic security for workers of color, women workers, and, in particular, women workers of color such as Black women and Native American women. This due to racial and ethnic and gender economic stratification stretching back centuries. Until this “double gap” is closed, the U.S. economy will remain inequitable, and equitable economic growth that is sustainable will remain out of reach.

This issue brief reviews the academic research on how anti-discrimination policies affect the life and economic outcomes of these historically marginalized groups of workers, the barriers that prevent government agencies from effectively protecting workers against unfair treatment in employment, and the policy solutions that can advance compliance with civil rights to achieve a more equitable labor market. Briefly, those policy solutions are to:

- Increase compliance with anti-discrimination laws and regulations by substantially increasing funding for the federal enforcement agencies so they can do their jobs

- Address gaps in anti-discrimination laws that exclude some of the most vulnerable workers and undermine their effectiveness, particularly for those who work for employers with fewer than 15 employees and are excluded from anti-discrimination enforcement

- Expand protected traits under anti-discrimination protections to include more characteristics associated with protected racial and religious groups

- Deploy and strengthen anti-discrimination enforcement strategies to monitor industries and employers especially likely to violate anti-discrimination laws, especially in lower-paying industries, among a relatively small number of employers, and during economic downturns

- Invest in robust income support infrastructure that improves outside options of finding new employment to ensure workers and families are protected against negative income shocks, including the loss of jobs or forms of retaliation in the face of employment discrimination

- Boost worker power essential for the effective enforcement of anti-discrimination protections by fostering the growth of unions and institutionalizing norms of fairness and equity

But first, let’s turn to the history of anti-discrimination laws and practices to understand how policy solutions to today’s illegal practices are embedded in our existing U.S. labor laws and labor market institutions. The tools to create more equitable and safe workplace environments for all U.S. workers are already crafted, albeit with limitations at their inception—they just need to be updated for 21st century workplaces and wielded again for the good of all workers to achieve a more robust and equitable economic growth.

The creation of the two federal government agencies responsible for enforcing anti-discrimination laws and regulations

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, the U.S. Congress passed a number of landmark pieces of legislation with the objective of advancing anti-discrimination protections in employment.1 The Equal Pay Act of 1963 made it illegal for employers to pay men and women different wages for equal work, including safeguards against retaliation for anyone who filed an equal pay claim. The following year, Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed workplace segregation and discrimination by race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.2

In addition, Title VII introduced the principle of equal opportunity to all phases of employment, banning discrimination in hiring, firing, promotions, training, wages, and benefits. A year after the enactment of the Civil Rights Act, the federal government created the independent Equal Employment Opportunity Commission to oversee compliance with Title VII.

Although the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission originally did not have the authority to sue employers for civil rights violations, it could investigate and mediate charges of employment discrimination. The commission also issued guidelines, made technical studies, and required larger employers to submit annual reports on the racial, ethnic, and gender composition of their workforce.

That same year, President Lyndon Baines Johnson signed Executive Order 11246, which established the Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs at the U.S. Department of Labor and banned federal contractors and subcontractors from discriminating against applicants or employees. The mandate also required contractors to “take affirmative action to ensure that applicants are employed, and that employees are treated during employment, without regard to their race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.”

Specifically, Executive Order 11246 required federal contractors to develop affirmative action plans, set goals, and make good-faith efforts to address any underrepresentation of women and people of color in their workforces and among higher-level positions.

Over the following decades, both of these federal agencies were given greater enforcement powers.3 In addition to overseeing compliance with Title VII, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission is now responsible for enforcing the Equal Pay Act, as well as for enforcing the laws that ban discrimination on the basis of disability, age,4 or genetic information.5 The commission’s key responsibilities include investigating and mediating charges of discrimination, filing lawsuits against employers or labor organizations thought to be in violation of Title VII, securing compensation for victims of unfair treatment at work, and conducting outreach to educate both workers and employers about their rights and responsibilities under federal anti-discrimination law.

Likewise, in the late 1970s, the responsibility for enforcing affirmative action obligations among federal contractors was consolidated in the Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs. The agency, which currently covers about 25 percent of the U.S. workforce, is in charge of ensuring that employers doing business with the federal government comply with anti-discrimination laws by reviewing contractors’ affirmative action plans, investigating discrimination claims, conducting audits, and obtaining financial relief for employees and job-seekers who have suffered unfair treatment.

Affirmative action and anti-discrimination laws initially led to a more integrated U.S. labor market by race, ethnicity, and gender

Federal anti-discrimination laws and regulations played an important role in improving the employment and occupational standing of historically marginalized workers between the late 1960s and the turn of the 21st century. When examining the effect of equal opportunity protections on the private sector, a team of scholars found that U.S. workplaces were extremely segregated in the mid-1960s. In 1966—the first year the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission collected data on the employment and occupational composition of U.S. workplaces by race, ethnicity, and gender—about half of reporting establishments did not have any Black men as employees.6 More than 70 percent did not employ any Latino men or Black women, and 85 percent did not employ any Latina women. At least 90 percent of reporting business establishments did not employ Asian American men or women.

But in the decades that followed, this kind of segregation fell. Donald Tomaskovic-Devey at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and Kevin Stainback at Purdue University demonstrate that as the enactment of the Civil Rights Act increased political and social pressure to integrate workplaces, many workers were able to hold jobs in establishments from which they had previously been excluded. As such, by the early 2000s, almost 80 percent of reporting establishments employed Black men, 72 percent employed Black women or Latino men, 65 percent employed Latina women, and 55 percent employed Asian American men or women.

Overall, then, by 2002, nearly all establishments that report data to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission employed at least one worker of color.

Affirmative action also helped reduce segregation in employment. The evidence shows, for instance, that especially during the 1970s and early 1980s, the share of Black and Native American workers increased more in firms subject to affirmative action obligations than in otherwise-similar firms. In addition, when studying the effects of the policy, Conrad Miller at the University of California, Berkeley’s Haas School of Business found that 5 years after an establishment becomes a federal contractor or subcontractor, the share of its employees who are Black rises by an average of 0.8 percentage points.

Miller shows, moreover, that the Black share of employment continues to rise even as a firm stops being a federal contractor, proposing this happens because employers makes investments and changes to their screening and hiring practices that persist even after they are no longer subject to affirmative action regulations.

As the anti-discrimination legislation of the mid-1960s removed most formal barriers to education and employment opportunities, many historically marginalized workers also were able to access higher-paying jobs. Research by Fidan Ana Kurtulus at the University of Massachusetts Amherst shows that affirmative action played a role in the occupational advancement of Black men and women, Latina women, and White women by creating new pathways for these workers to move up the career ladder and access managerial, professional, and technical positions.

Access to more and better jobs, in turn, contributed to narrowing wage divides in the U.S. labor market. There is evidence, for example, that as the 1972 Equal Employment Opportunity Act extended coverage of anti-discrimination protections under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act to businesses with 15 or more employees instead of the previous 25 or more employees, the share of Black men in well-paying jobs rose, and the earnings gap between Black and White men narrowed.7

Similarly, a team of scholars finds that the Equal Pay Act of 1963 and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 set in motion the passage of other anti-discrimination laws and protections that, together, narrowed the pay gap between men and women. Yet amid these advancements in more equitable workplaces across the nation, there also were signs that progress was slowing in the last two decades of the 20th century.

Progress toward a more fair and equitable U.S. labor market slowed beginning in the 1980s

For most groups of workers, advancement toward a more even occupational distribution and narrower wage divides began to lose steam after the early 1980s. Among the many reasons why this happened in the last two decades of the 20th century were the continuation of a decades-long drop in union membership, the erosion in the real value of the federal minimum wage, and the proliferation of low-paying, bad-quality jobs.

What’s more, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and the Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs responsible for enforcing anti-discrimination laws and affirmative action mandates became less and less effective at driving workplace integration and fostering employment opportunities for protected classes. There is evidence, for example, that the positive effect of affirmative action in the employment and career advancement of workers of color and women workers weakened substantially during President Ronald Reagan’s two terms in office.

The reason, several scholars argue, is that the political commitment to affirmative action dwindled as the Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs came under new leadership. Indeed, the Reagan administration tried and failed to revoke Executive Order 11246 and, amid the effort and afterward, continued to oppose serious enforcement of the affirmative action statutes and regulations. And so, during the 1980s there was a decline in the number of sanctions issued for noncompliance, fewer firms were required to adopt affirmative action plans, and compliance reviews rarely found that women workers or workers of color were unfairly underrepresented in contractors’ workforces.

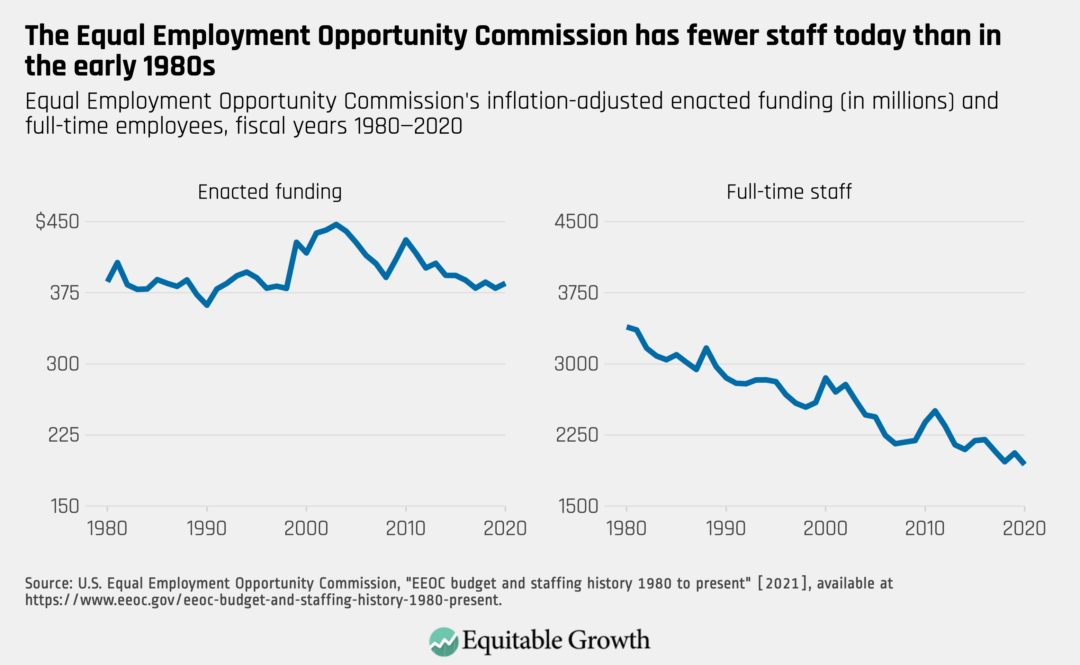

Something similar happened with the oversight of civil rights under Title VII. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission was given greater enforcement powers and responsibilities throughout the 1970s.8 But in the 1980s, the agency was overwhelmed by both a massive increase in the number of charges it needed to process and a budget shortfall that forced it to reduce its staff.

To be sure, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission has struggled with capacity constraints and a backlog of unresolved charges through most of its history. But the early 1980s marked an inflection point for the agency, after which it experienced a consistent decline in personnel that continued unabated over the past 40 years.

Federal anti-discrimination enforcement agencies often lack the tools to protect workers against employment discrimination

The work of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and the Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs definitely allowed many workers to hold jobs that they were previously kept from holding due to discrimination, as well as to have stronger protections against unfair treatment at work. Yet insufficient funding, understaffing, and issues embedded in the institutional design of the two federal anti-discrimination enforcement agencies often keep them from ensuring compliance with anti-discrimination laws and regulations.

A large share of U.S. workers today report facing employment discrimination. According to a recent survey by the job search-and-evaluation company Glassdoor Inc., more than 60 percent of employees have either experienced or witnessed discrimination at work. Similarly, the 2016 General Social Survey found that just less than 20 percent of U.S. adults had faced discrimination in a job application, a pay bump, or a promotion in the previous 5 years.

By one estimate, 26 percent of Black workers and 15 percent of Latino workers are treated unfairly at work because of their racial or ethnic background. An AARP study found that 64 percent of older women and 59 percent of older men experience workplace discrimination because of their age. Just less than half of LGBT workers have experienced unfair treatment at work, according to a recent study by the Williams Institute at the University of California, Los Angeles.

The vast majority of cases of workplace discrimination, however, are not reported. Very few cases of discrimination are brought forth within workplaces, and even fewer are reported with government enforcement agencies. By one estimate, less than 1 percent of the workers who experience any kind of unfair treatment on the basis of sex, race, or another protected characteristic file a formal charge.

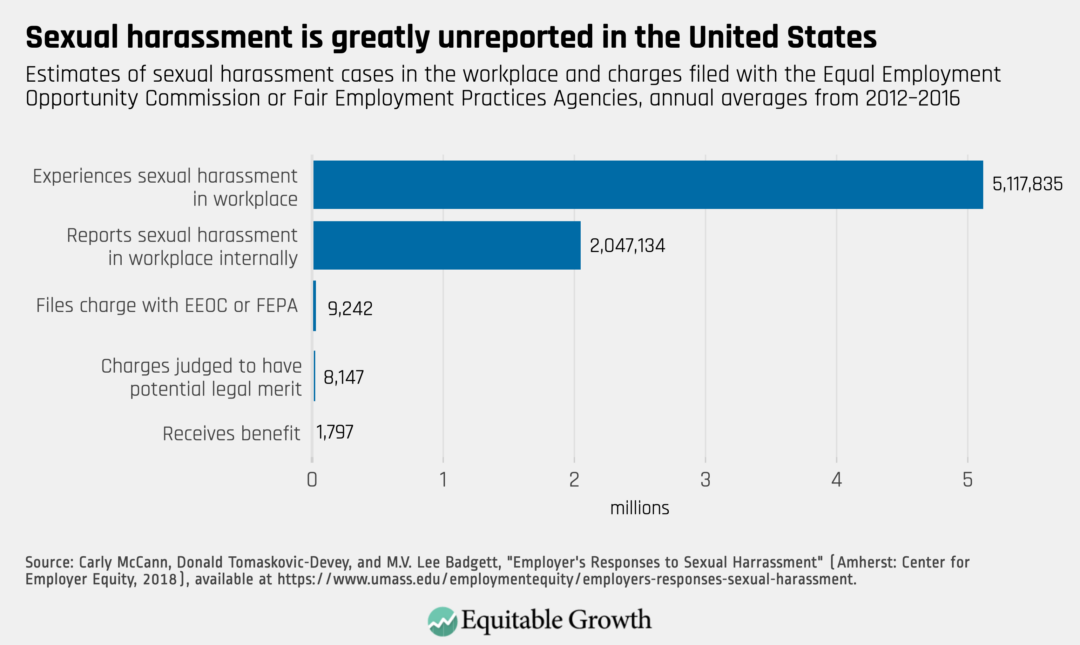

And according to the Center for Employment Equity at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, of the 5 million employees who experience sexual harassment at work every year, fewer than 10,000—or about 0.2 percent—file charges with either the federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commission or state Fair Employment Practices Agencies. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

One important reason why workers do not report cases of employment discrimination is the threat of retribution or retaliation, where a worker is fired, demoted, or harassed for opposing discrimination or filing a complaint. This fear is far from unfounded. An analysis of charges filed with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission between 2012 and 2016 found, for instance, that almost 2 in 3 workers who filed a complaint with the agency eventually lost their jobs.

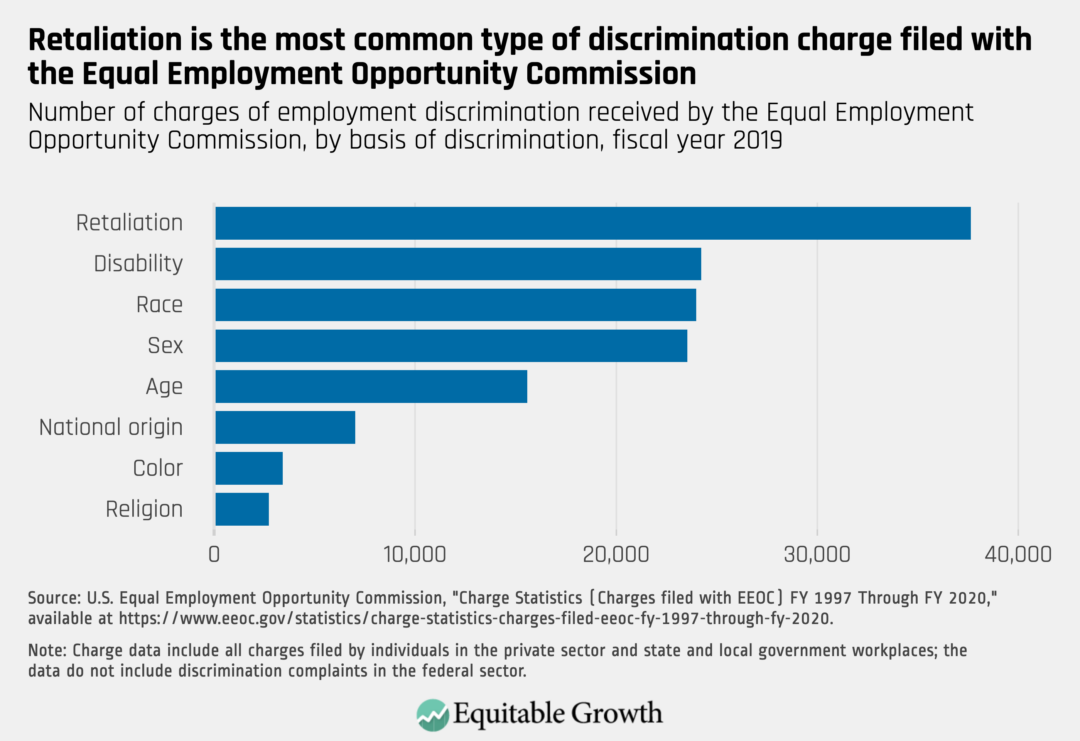

Then, there’s the official data that show in fiscal year 2019, more than half of all discrimination claims received by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission—54 percent—were charges of retaliation.9 The next most common types of discrimination claim were for disability, race, or sex-based discrimination. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

For those relatively few cases that are reported to a federal or state government enforcement agency, the probability that the worker receives some form of relief is also small. According to an analysis by The Washington Post and the Center for Public Integrity, out of the more than 1 million discrimination complaints workers filed with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission or state Fair Employment Practices Agencies between fiscal years 2010 and 2017, only in 18 percent of the cases did these workers either receive a monetary compensation or experience a change in work conditions. Claims of racial discrimination have the lowest success rates—15 percent end with the claimant receiving some form of relief.

These failures are, in large part, because the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and the Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs have long suffered from inadequate funding and staffing, hurting the agencies’ capacity to effectively protect workers against discrimination. A 2018 survey of federal workers found, for instance, that 45 percent of Equal Employment Opportunity Commission staff do not think they have enough resources to do their job, compared to 36 percent of employees across federal agencies.

Indeed, while the U.S. workforce had 60 million more employees in February 2020 (before the coronavirus recession began) than it did in 1980, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission receives roughly the same resources, after adjusting for inflation, as it did four decades ago. In fiscal year 2020, the agency employed only 1,939 workers—a 43 percent drop from fiscal year 1980. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

The effective enforcement of anti-discrimination laws is essential to foster equitable U.S. labor market outcomes and promote broadly shared economic growth

Discrimination in employment affects workers’ mental and physical health, increases job turnover, holds back upward career trajectories, and stymies workers’ ability to build wealth. By hurting the life and economic outcomes of workers who experience it, the unfair treatment of workers because of their race, gender, or other protected characteristics also reproduces longstanding inequities and robs the U.S. economy of talent that would otherwise make it more dynamic.

Here is what research shows about discrimination in hiring, firing, and promotions, as well as how harassment affects workers’ labor market outcomes.

Hiring

By outlawing discrimination in hiring, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 put the brakes on some of the most egregious forms of employment discrimination. Prior to the enactment of Title VII, job vacancy ads could be—and often were—explicitly discriminatory. Yet there is a robust academic literature finding that hiring discrimination on the basis of protected traits, such as age, sexual orientation, religion, gender, race, and ethnicity, continues today.

Here’s just one case in point: Field experiments—studies in which researchers send fictitious job applications to real job openings—conducted for several studies find that resumes with distinctively Black-sounding names are much less likely to be contacted by an employer than otherwise-identical resumes with White-sounding names. And then, there’s a meta-analysis of all field experiments conducted between 1989 and 2015, which found that White workers received, on average, 36 percent more callbacks than Black workers and 24 percent more callbacks than Latino workers.

Alarmingly, the authors of this meta-analysis also found that racial discrimination in hiring is about as prevalent now as it was in the late 1980s. Their study found no evidence that rates of hiring discrimination against Black workers had waned over the 26-year period, while hiring discrimination against Latinx workers fell only slightly.

Firing

Being fired is one of the most disruptive events a worker can experience. Workers who lose their jobs face lower job-finding rates when seeking new employment, are less likely to work as many hours as they did before, and experience a sharp drop in earnings that persists even after reemployment. Research also shows that while unemployed job-seekers in general are evaluated harshly when applying for a job, candidates who have been laid off are perceived as less competent than otherwise-similar unemployed job-seekers.

Some groups of workers are especially vulnerable to being laid off as general economic conditions deteriorate or businesses face trouble. There is compelling evidence that Black workers tend to be fired first as the economy contracts, as well as being more closely monitored than their White counterparts and therefore more likely to be fired for making a mistake.

Similarly, immigrant workers are more likely than U.S. citizens to involuntarily lose their jobs when a recession hits. A recent study using Equal Employment Opportunity data finds that—like other forms of discrimination—age-related firing and hiring claims increase during economic downturns. As such, discrimination in firing sets in motion a negative feedback loop in which workers belonging to one or more protected classes may be at higher risk of being laid off and therefore more likely to experience the negative consequences of losing a job.

Promotion

Discrimination in promotions keeps workers from moving up career ladders and holding positions that are a good match for their interests and skills. For the broader economy, one of the greatest contributors to the country’s racial, gender, and intersectional wage divides is the U.S. occupational structure that continues to be deeply segregated along the lines of race, ethnicity, and gender, and leaves some groups of workers especially exposed to economic shocks. Further, because occupational segregation sorts women and people of color—and women of color in particular—into lower-paying occupations, there is a persistent “double wage gap” faced by these women.

Scholars also find that Asian American women are less likely to reach positions of institutional power or to supervise big teams than otherwise-similar White women, and a team of researchers found that Black men are more likely to work in low-wage occupations and less likely to work in high-wage occupations than White men with the same level of formal education.

Discrimination in promotion also finds that these promotion divides have implications for broad economic dynamics. A team of researchers at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business and Stanford University find that as Black workers and women workers were increasingly able to pursue careers in professional and technical occupations, the better allocation of talent became a key driver of economic growth.

Harassment

Experiencing harassment—unwelcome conduct based on race, gender, sexual orientation, or another protected trait—is associated with worse mental and physical health outcomes, lower levels of job satisfaction, a decline in organizational commitment, and a drop in productivity. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission considers workplace harassment illegal when “enduring the offensive conduct becomes a condition of continued employment, or the conduct is severe or pervasive enough to create a work environment that a reasonable person would consider intimidating, hostile, or abusive.”

The largest number of sexual harassment claims to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission are filed by workers in the accommodation and food services and retail industries—sectors in which women of color are overrepresented and which are among the lowest-paying in the U.S. economy. Women are also especially likely to be victims of sexual harassment in men-dominated sectors such as construction.

Further, research by Matthew Knepper at the University of Georgia and Gordon Dahl at the University of California, San Diego find that during recessions, victims are less likely to report instances of sexual harassment with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. They argue this is the case because workers are more reluctant to face the threat of employer retaliation when the labor market is experiencing a downturn.

Policies to promote the effective enforcement of federal anti-discrimination laws

In the decades since the creation of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and the Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs, progress against discrimination at work has been both real and uneven. Workplaces and occupations are much less segregated now than prior to the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In general and by most measures, gender and racial wage divides are narrower today than in the 1950s.

Yet historically marginalized workers continue to face both systemic employment discrimination and unfair treatment at work that ultimately contribute to economic inequality, lost talent, and constrained economic growth. Effective enforcement of anti-discrimination protections is a first step toward challenging systems that maintain racial and gender economic divides.

A first step to increase compliance with anti-discrimination laws and regulations is to substantially increase funding for federal enforcement agencies. The large number of discrimination complaints filed with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, its charge backlog, and its data collection responsibilities all highlight the need for Congress to allocate more resources for the agency. Doing so would not only prevent further personnel cuts but also ensure the commission’s budget is appropriate for the agency to effectively enforce the country’s anti-discrimination laws by, for example, hiring and training staff, modernizing its data-collection processes, and addressing pending complaints.

Second, policymakers should address gaps in anti-discrimination law that exclude some of the most vulnerable workers and undermine its effectiveness. Title VII does not apply to employers with fewer than 15 employees. Self-employed workers are also excluded from federal anti-discrimination laws. As a result, some of the most vulnerable workers in the U.S. economy—many domestic and agricultural workers, who are often employed as independent contractors or may not be currently documented—are excluded from Title VII protections.

The federal government could also follow states and municipalities that have expanded protected traits under anti-discrimination protections. For instance, New Jersey, California, New York City, and the District of Columbia all have expanded protections for workers based on hairstyle, which further protects U.S. workers based on mutable characteristics associated with a protected racial and religious group, such as dreadlocks or cornrows, where workers may be subject to additional scrutiny and discrimination based on racialized characteristics beyond a binary category of racial identity.

Third, enforcement agencies should use their resources to monitor industries and employers especially likely to violate anti-discrimination laws. Workplace discrimination is especially prevalent in lower-paying industries, among a relatively small number of employers, and tends to increase during economic downturns. This highlights the need for what Janice Fine, Jenn Round, and Hana Shepherd of Rutgers University and Daniel Galvin of Northwestern University call strategic enforcement—the targeting of high-violation sectors and the ramping up of enforcement powers during recessions to increase the cost of noncompliance.

Fourth, a robust income support infrastructure that improves outside options is a key complement to anti-discrimination policies. Social infrastructure programs, such as Unemployment Insurance, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, and Medicaid, are essential to ensure workers and families are protected against negative income shocks, including the loss of jobs or forms of retaliation in the face of employment discrimination. These programs give workers facing unfair treatment—whether it be a hostile work environment or additional difficulty finding adequate employment due to discrimination—the economic security and time necessary to make decisions that are in their long-term interests, including reporting cases of discrimination.

In the case of sex discrimination, for instance, evidence suggests that workers facing less generous Unemployment Insurance benefits are less likely to report experiencing workplace sexual harassment. This suggests that fear of retaliation and the threat of economic insecurity play an important role in victims’ decisions to not raise instances of discrimination. Economic security outside of employment improves workers’ position to proactively address workplace discrimination.

Finally, few employers are held responsible for workplace discrimination, which is both a byproduct and a reflection of fundamental power imbalances in U.S. employment relationships, making policies that support organized labor and boost worker power essential for the effective enforcement of anti-discrimination protections. Labor unions often protect workers against discrimination by bargaining for pay transparency and fairness in promotions and hiring, narrowing gender and racial wage gaps, and establishing grievance processes.

More broadly, unions help foster and institutionalize norms of fairness and equity. Recent research by Paul Frymer at Princeton University and Jacob Grumbach at the University of Washington shows, for example, that when White workers become part of a union, their support for affirmative action, as well as for policies that benefit Black communities in general, increase.

By hurting the workers who experience it, employment discrimination deprives the overall economy of talent and dynamism. Federal anti-discrimination efforts were essential in creating a more fair, equitable, and dynamic labor market after the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Today, the effective enforcement of affirmative action and equal opportunity provisions can help narrow persistent and longstanding inequities in U.S. workers’ labor market outcomes that have diminished allocation of talent and held back workers from sharing in the economic growth to which they contribute. Lessening discrimination against workers is a basic building block of an equitable labor market.

—Carmen Sanchez Cumming is a senior research assistant at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth.

End Notes

1. Prior to the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, a number of states had enacted fair employment practices laws, which outlawed discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, national origin, or ancestry.

2. The Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978 amended Title VII of the Civil Rights Act to include pregnancy and childbirth as a form of sex discrimination. In 2020, the Supreme Court held that employment discrimination on the basis of an individual’s sexual orientation or gender identity is a form of sex-based discrimination.

3. Several states have additional anti-discrimination laws and regulations. For instance, the District of Columbia prohibits the unfair treatment of people at work on the basis of their marital status, personal appearance, family responsibilities, or political affiliation; North Dakota makes it illegal for employers to discriminate on the basis of receipt of public assistance; California includes people with AIDS/HIV, veteran or military status, and status as a victim of domestic violence, assault, or stalking as protected characteristics.

4. For those 40 years old and over.

5. Genetic information encompasses information about genetic tests and information about the manifestation of a disease or disorder in someone’s family members. According to Title II of the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008, it is illegal for employers and labor organizations to request genetic information or an individual’s family medical history.

6. These data come from EE0-1 reports—establishment surveys collected by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Initially, EEO-1 reporting requirements included private-sector employers with at least 50 employees and federal contractors with at least 25 employees. After 1983, EEO-1 reporting requirements included private-sector employers with at least 100 employees and federal contractors with at least 50 employees.

7. In 1965, private-sector employers with at least 100 employees were covered; in 1966, employers with at least 75 employees were covered; in 1967, employers with at least 50 employees were covered; in 1968, employers with at least 25 employers were covered. After 1972, employers with 15 or more employees were covered.

8. President Jimmy Carter transferred the responsibility of enforcing the Equal Pay Act of 1963 and the Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967 from the U.S. Department of Labor to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

9. The Center for Employment Equity finds that a massive 68 percent of the sexual harassment charges made to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and state Fair Employment Practices Agencies between 2012 and 2016 included reports of employer retaliation. Black women were especially likely to face retaliation when reporting cases of sexual harassment.