The economic costs of gun violence in the United States

Overview

When it comes to understanding the costs of gun violence in the United States, many people rightfully focus on the human cost. People who are slain or take their own lives, their family members who suffer in the aftermath, and the communities afflicted by their losses are often centered in media coverage and conversations about gun violence. Yet whether caused by a mass shooting, assault or homicide, act of suicide, or police shootings, we all pay for the costs of gun violence in expected and unexpected ways.

In fact, the human toll of gun violence is so pervasive that its consequences permeate nearly every facet of U.S. society, including economics. Examining the economic consequences of gun violence, however, is not intended to put a price on human life. Rather, the aim is to provide a deeper understanding of just how extensive and ubiquitous gun violence is in the United States.

It is near impossible to sum up all of the monetary costs of gun violence in the United States. Estimates attempting to do just that have ranged from $229 billion to $280 billion, and all the way up to $557 billion per year. Such a wide range is not much of a surprise, considering the lack of reliable data and different assumptions that go into making these calculations.

All of these numbers, however, fail to encapsulate the total cost. This includes the psychological costs of gun violence, such as the emotional burdens of living in fear and the ongoing traumas experienced by individuals and communities. Then there are the indirect monetary costs that are often unaccounted for, such as lost investments and business opportunities, as well as macroeconomic harms. As a result, any overall estimates or numbers are more likely to be a lower-bound estimate rather than a complete picture.

What makes an accounting of the economic costs even more challenging is that holistic data on the economic cost of gun violence is hard to come by. There are few comprehensive studies, limited public and private funding, and some limits on how much data can be released to the public. Compounding these problems is the politicization of gun violence, reflected in the legislative fight over directing resources just toward studying the issue.

Indeed, the so called Dickey Amendment, first instituted in 1996, prevented the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention from using any funding “to advocate or promote gun control,” essentially shutting down government research on the topic until Congress clarified the law in 2018 and funding was first allocated in 2019. The result is that we’re left piecing together what few studies do exist, limitations and all, to try and get a better sense of how much gun violence costs our country.

Academics and policymakers alike may be lacking data on measuring these costs and understanding how much value our society loses to gun violence, but we do know some of the root causes behind certain components of gun violence. For instance, research finds that income inequality, concentrated poverty, underfunded public housing, under-resourced public services, and underperforming schools are all conditions that tend to increase the likelihood of gun violence within a given community.

Moreover, increases in deaths at the hands of White supremacists and related extremists, easy access to guns, lack of strict regulations, the loneliness epidemic, and police violence all play a role in continuing and escalating the vicious cycle of gun violence we see in the United States.

This issue brief can’t explore all of these causes in detail. But it is important to remember that many of the costs outlined below fall on all of our society via public funding being directed toward security infrastructure for schools instead of other educational programs, reduced tax base due to limited business activity in areas suffering from gun violence and crime, and funding from federal government, states, and localities spent on healthcare costs for those who are uninsured. What’s more, gun violence reflects and worsens racial and income inequalities. Black Americans, for example, are 10 times more likely than White Americans to die by gun homicide, and young people are more likely to die from gun violence in areas where poverty is more highly concentrated.

This issue brief examines different areas where the economic costs of gun violence have been most completely measured in order to provide a comprehensive look at where the costs come from and their impact on U.S. society. Specifically, I look at the cost of gun violence as it relates to:

- Healthcare

- Employers and businesses

- Wages and human capital

- Communities

I then conclude with a look at the need for more timely studies to be conducted, more data to be collected, and more public and private funding dedicated to researching this problem. These are just some of the necessary steps to get a more holistic understanding of the scope of the problem and inform future evidence-based policymaking to address the issue.

Healthcare costs

Some of the biggest monetary costs that gun violence imposes on our society are related to healthcare. Trips to the emergency room, ambulance rides, inpatient care, physical therapy, and ongoing emotional and mental trauma that survivors must endure all add up to significant sums of money. Similar to overall estimates, the healthcare-related costs of gun violence fail to encapsulate the true costs. This is due to a variety of reasons, most notably because many survivors of gun violence face barriers to receiving the care they need—due to the cost of care or access to care—or choose not to seek medical assistance.

When looking at the topline numbers of healthcare costs, there are plenty of estimates indicating an increase in the cost of gun violence over time. One study found that U.S. hospitals spent $630 million in medical treatment in 2010 alone, and another showed an average of $734.6 million per year from 2006 to 2014. A more recent study indicates more than $1 billion in annual spending in 2016 and 2017 on initial hospital costs.

More recent estimates indicate this cost could be even higher—as much as $1.57 billion annually. Yet even these studies fail to encapsulate all the costs. The average of $734.6 million per year fails to include emergency room visits or readmissions, and the $1 billion spent in 2016 and 2017 doesn’t include physician costs. The true costs of hospitalization from these estimates are even higher—in the latter’s case adding around 20 percent to the total cost.

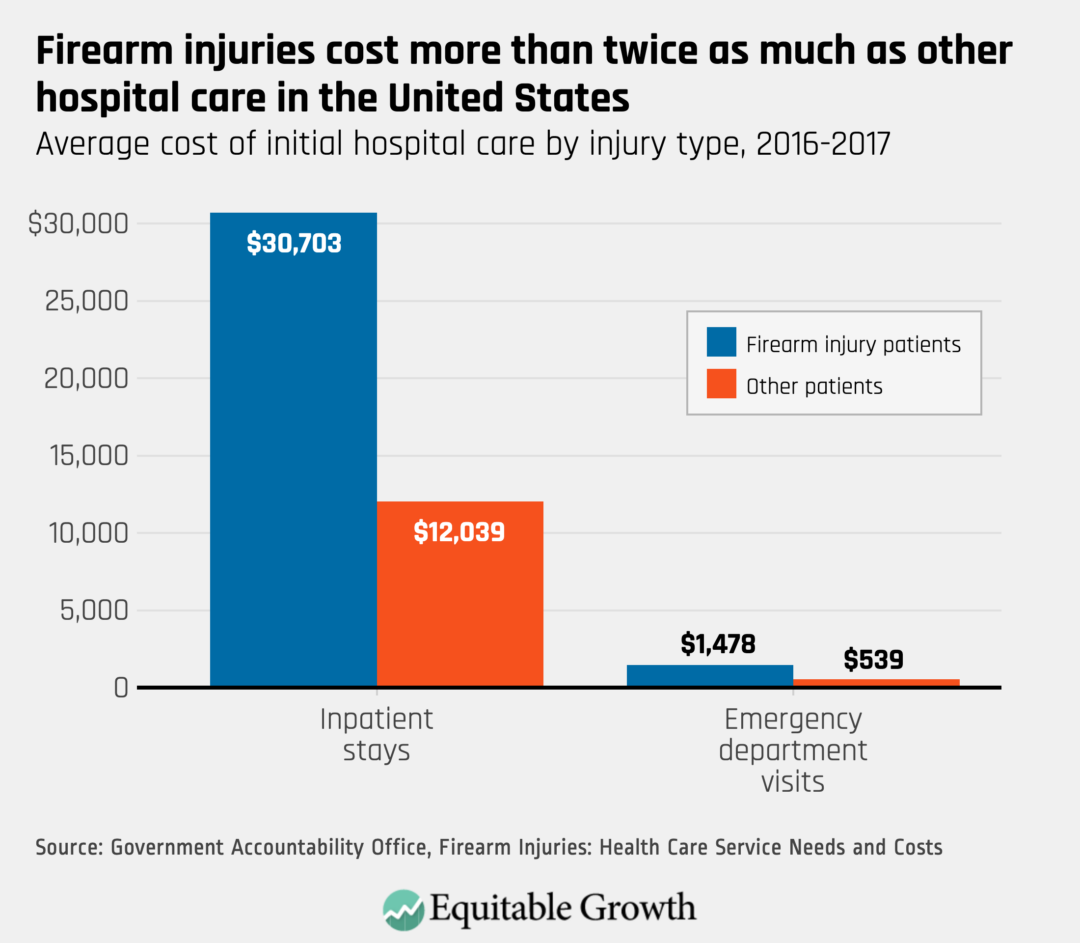

Inpatient stays are the main driver of healthcare costs. One recent study finds that more than 90 percent of initial hospital costs from 2016–2017 were driven by inpatient stays, even though they are less common than those who only received treatment in emergency rooms. That same study also finds the average cost of initial treatment for a gunshot wound—either in an emergency room or inpatient care—was more than twice the average cost of treating other patients.

Looking at this data more closely, one study found that from 2010–2015 the average annual cost of inpatient hospitalizations for firearm injuries exceeded $900 million. Another study found annual inpatient costs averaged more than $700 million between 2006 and 2014. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

For fatal firearm injuries, the costs are relatively straightforward. Data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention from 2020 shows that fatal firearm injuries cost a total of $290 million, with an average cost of $9,000 per patient. But for survivors of gun violence, the ongoing costs can multiply exponentially.

One recent study finds that among those who survived a nonfatal firearm injury between 2008 and 2018, medical spending increased by $2,495 per person per month—or 402 percent—compared to peers who weren’t exposed to gun violence. That same study finds most of this increase is within the first month after surviving a shooting, when per person costs increased by an average of $25,554. Up to 16 percent of those who experienced a firearm injury required readmittance, facing an average cost of $8,000 to $11,000 per patient. Between 2010 and 2015, approximately one in six patients with a firearm injury was readmitted within six months, with costs exceeding a total of $500 million over that time span.

Another method used to encapsulate the ongoing cost of gun violence on people’s well-being are quality-of-life costs. The loss of quality of life represents the present value of a victim’s life that was either cut short or permanently damaged by gun violence, and usually excludes the cost of medical care and lost work. One estimate put this cost at $169 billion per year in 2015, but more recent estimates indicate this number has ballooned to approximately $489.1 billion.

It’s worth noting there is a lack of contemporary studies looking at the total lifetime costs of injuries caused by gun violence. Any studies that currently exist are so outdated they’re no longer a reliable indicator of the totality of healthcare costs due to gun violence. This highlights the need for an ongoing collection of data over time to get a more complete sense of the true scope of healthcare related costs of gun violence. (See sidebar.)

Longer-term healthcare costs of gun violence

While there hasn’t been much research into the total lifetime cost of gun violence, there has been research looking at some of the longer-term healthcare costs—most notably related to mental health and the families of survivors.

One recent study finds that nonfatal firearm injuries lead to increases in psychiatric disorders, substance use disorders, and healthcare spending and use in the month immediately after the injury. Another recent study finds similar trends among gun violence survivors, but with an additional 40 percent increase in pain diagnoses and an increase in the use of pain and psychiatric medications. A third study finds that children who were exposed to a fatal school shooting in their area led to a 21 percent increase in antidepressant use in the two years following the incident.

As of 2015, the estimated direct cost of mental health-related expenses totaled $410 million annually. It is worth noting that this estimate has almost certainly increased commensurate with the increase in gun violence, and it would be even higher if all victims and families could afford or desired to seek out counseling.

These mental health costs also spread to more people than just immediate survivors. Family members experiencing gun violence had a 12 percent increase in psychiatric disorders compared to families who did not. Some gun violence survivors have injuries so severe that family members are compelled to become caretakers, therefore forgoing educational, professional, and economic opportunities. This in turn not only causes lost sources of income among the entire family, but also a general diminishing of quality of life among family members.

Disparate impact on low-income people and people of color

Much like other costs of gun violence, healthcare costs incurred from gun violence have a disproportionate impact on low-income people and people of color. This starts with the location of gun violence itself. Residents in the lowest income zip codes are approximately twice as likely to be admitted to an emergency room or hospital for a firearm injury. As median incomes increase, gun injuries decrease.

One study found that about 41 percent of initial hospitalization costs for gunshot wounds in 2006–2014 were for patients covered by Medicare or Medicaid. That same study also found that shooting victims who are covered by Medicaid had the highest per incident costs, averaging more than $30,000 per initial hospitalization—$7,000 more than privately insured patients. More recent studies corroborate these findings, with Medicaid and other public coverage accounting for more than 60 percent of annual costs of care related to gun violence in 2016–2017.

This situation is even bleaker for those who do not have insurance. Victims of firearm assaults are disproportionately more likely to be uninsured, and trips to the emergency room and hospital admissions for the uninsured occur nearly three times more often and more than twice as often, respectively, compared to the national average. Unfortunately, many who are uninsured then struggle to pay their hospital bills. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services found that only 12 percent of uninsured families could pay their hospital bills in full, and that uninsured people with incomes above 400 percent of the Federal Poverty Level could only fully pay for 37 percent of their hospitalizations.

These costs only encapsulate a fraction of the suffering caused by gun violence in low-income communities and communities of color. Many members of these communities are more likely to face barriers to accessing healthcare in the first place due to systemic inequities. Hospital policies and resources, for example, may prevent a survivor from getting follow-up care at that same hospital, patients may be denied access to rehabilitation facilities due to lack of insurance, and racial bias in the health system may prevent doctors from prescribing treatment to patients of color.

Impacts on employers and businesses

Employers lose approximately $535 million per year in direct costs from gun violence due to lost revenue, time spent adjusting schedules to cover for lost work, and training new replacements for vacancies. Businesses that rely on customer interactions, most notably the retail and service sectors, may see their revenues drop faster than other businesses due to patrons shopping in safer communities to avoid the threat of gun violence.

These issues are compounded by owners facing trouble hiring employees willing to travel through or work in communities plagued by gun violence. These factors cause many businesses to close their doors outright, but those which stay open often incur costs on items such as camera systems, bulletproof windows, motion sensor lights, barred doors, and security staff. Spending money on security measures such as these prevent entrepreneurs from investing that money elsewhere in their businesses or communities.

But the costs incurred by businesses exceed changes to physical infrastructure. Many entrepreneurs choose to open their businesses in safer neighborhoods, representing lost economic value in communities plagued by gun violence. Fear of gun violence also stops people from shopping in a certain neighborhood at night, if they even decide to shop there in the first place. Other studies also found that crime and fear of crime adversely impact retail development and limit business activity and revenues.

Indeed, a more recent study finds that sudden surges in gun violence is associated with as much as a 4 percent reduction in new retail and service establishments in major cities across the country. That same study also finds that one additional gun homicide in Minneapolis in a given year results in 80 fewer jobs the next year.

This loss of revenue has broader implications beyond individual businesses. Phenomena such as enduring neighborhood segregation and increased crime lead to lower tax revenues, in turn impacting economic mobility. For instance, one recent study finds that reduced tax revenues from property taxes reduces public safety expenditures per capita, and reduced school expenditures leads to less spending per pupil. This adds up to fewer opportunities for individuals and families living in these communities to benefit from economic mobility.

Many communities struggling with gun violence also suffer from myriad other disadvantages, many of which lay the groundwork for more gun violence to take place. Systemic lack of investment in historically underfunded neighborhoods and cities, income inequality, limited economic opportunities, concentrated poverty, underperforming schools, lack of access to food, shortage of affordable housing, and police violence all play a role in perpetuating the vicious cycle of gun violence. Indeed, 26 percent of firearm homicides in 2015 in the United States took place in U.S. Census Bureau tracts that contained only 1.5 percent of the population.

Impacts on human capital and wages

Gun violence has an overall negligible impact on productivity. Typical measurements of productivity only account for regular production through labor market earnings and household production. But victims of gun violence engage in other activities outside of the market and household, both for better and for worse. Some positive examples include volunteering for local organizations or caregiving for family members and friends. On the flip side of this coin, data from Washington, DC indicates that about 86 percent of homicide victims and suspects were known to the criminal justice system in some way due to previous property crimes, drug crimes, or unarmed violent offenses.

One of the biggest costs of gun violence is lost wages. This can be defined as the value of work an individual is unable to do as a result of injury, disability, or death. Calculations for this also include wage equivalents for unpaid household and caregiver work on behalf of victims. A 2015 estimate found that the U.S. economy loses approximately $49 billion every year in lost wages, and by 2022 this increased to $53.77 billion due to gun violence. Considering individuals living in households with a median income of less than $44,000 per year account for 6 in 10 nonfatal firearm assault injuries, these lost earnings have a disproportionate impact on people who are already struggling to make ends meet.

Economic impact of school shootings

When it comes to gun violence, few things garner more attention than a mass shooting at a school. The results of these events are traumatic, and they too impose tremendous monetary costs on our society. The school shooting in Uvalde, TX in 2022 cost an estimated $244.2 million alone, including direct and indirect costs related to healthcare and lost wages respectively. Just like other costs of gun violence, the costs of both physical alterations to schools to increase safety and negative educational consequences that come from school shootings have a ripple effect on survivors and communities.

School shootings have a lasting impact on students who survive them. One recent working paper finds that surviving a school shooting increases rates of absenteeism and grade repetition, reduces the likelihood of graduating high school by 4 percent, reduces the likelihood of attending college by 10 percent, reduces the likelihood of graduating college by 15 percent, and decreases employment rates and earnings at ages of 24 and 26.

Other studies find similar results, both in the United States and abroad. Research also finds that school shootings decrease retention rates among teachers and support staff in the years following a shooting. These effects show up in schools across the country. Schools in Texas that experience a shooting see a 12 percent increase in absences, 28 percent increase in chronic absenteeism, and the rate of grade repetition more than doubles. High school students in California who remained enrolled in school after experiencing a shooting had lower standardized test scores, and students who survived the Sandy Hook shooting registered decreased test scores in math and English.

U.S. schools and colleges spent $3.1 billion in 2021 just on increasing school security through infrastructure, products, and services. This number is expected to increase by 8 percent each year, and doesn’t include billions of dollars more that are spent on armed law enforcement officers patrolling school campuses. Additional police presence in schools are ineffective at making schools safer, help drive the school-to-prison pipeline, disproportionately impact students of color, and are associated with a host of other negative consequences for students, including reduced instructional time, attendance, and on-time graduation rates.

Other reports indicate that schools spent more than $150 million in federal dollars on school safety and security since 2018, and at least $811 million for security guards in school districts since the mass shooting at Columbine High School in 1999. This nationwide trend is occurring at the state and local level. Approximately 90 percent of U.S. school systems made security enhancements in the three years following the Sandy Hook shooting in 2012. This spending places an undue strain on state, local, and individual school budgets, diverting funds away from educational efforts and toward increasing school security measures.

Broader, community-level costs

Many of the costs imposed on our society by gun violence can be calculated, however imprecisely, but there are lots of other knock-on effects that are difficult to capture.

One example are costs associated with the U.S. criminal justice system. Lawyers for courtroom hearings, court administrative staff and processing, filling prisons with people, and police responses and investigations are all tangible costs caused by of gun violence. One estimate finds that these criminal justice costs totaled $11.01 billion per year. Another study found that $5.2 billion alone comes from long-term prison costs for those who commit assault or homicide with a firearm.

These costs are necessary in order to ensure people who commit harm to others with a firearm are prevented from continuing to do so. Yet a fundamental reason why these costs are so high is the easy access to guns and the sheer volume of guns currently in circulation in the United States. A nation awash in guns increases the likelihood that violent situations become more lethal and land more people in the criminal justice system. A domestic abuser with access to a firearm, for example, makes it five times more likely that a woman will be killed.

Other indirect costs from gun violence impact wealth inequality through a variety of facets. There are several studies, for example, showing links between increasing crime rates and decreasing property values and other negative consequences. While these studies look at the overall crime rate, it’s worth remembering the prevalent role of firearms when crimes are committed. While this research sheds light on some of the negative impacts of gun violence, there’s less information exclusively examining the broader impact of gun violence on communities.

One study found that surges in gun homicides slowed home value appreciation by 3.9 percent across multiple U.S. cities and led to decreased credit scores in certain census tracts. More specifically, it found that each additional gun homicide in 2014 was associated with:

- A $22,000 decrease in average home values in Minneapolis census tracts and a $24,261 decrease in Oakland, CA census tracts

- A 3 percent decrease in homeownership rates in Washington, DC

- A 20-point decrease in average credit scores in Minneapolis census tracts and a 9-point decrease in Oakland, CA census tracts

That same study also found that increased rates of violence led to higher rates of relocation away from the area, therefore increasing vacancy rates and lowering home prices due to absentee homeownership.

Because the United States relies on homeownership as a primary means of wealth-building, the negative impacts on housing values caused by gun violence in these communities affects the wealth generation of people living in those areas. Indeed, homeownership among Black families makes up an even greater share of household wealth than other families. Combined with the enduring consequences of redlining and other forms of racial discrimination in housing markets, this reliance on homeownership for wealth generation exacerbates the wealth gap between Black and White families. For Black families living in communities with high rates of gun violence, their main form of wealth accumulation is increasingly compromised.

The indirect, negative consequences of gun violence aren’t limited to just housing and credit scores. The overarching fear of crime and gun violence, and people’s perceived risk of gun violence, has been shown to impose a wide range of social and psychological burdens and costs. The emotional burden of fear weighs on everyone in a community—residents, employees, and visitors alike. Costs such as these are hard to calculate and don’t typically make the headlines, but they have a very real and tangible impact on the people who live in communities plagued by gun violence.

Conclusion

The costs of gun violence to the U.S. economy and society outlined in this issue brief are only the tip of the iceberg. More needs to be done to get a more all-encompassing picture of the complete cost that gun violence inflicts on the United States. More timely studies must be conducted, more data needs to be collected and released, and more public and private funding needs to be dedicated to researching this deadly problem. A concerted effort among public and private stakeholders to help fill the void of recent, timely research and data on the costs of gun violence would help U.S. policymakers and academics alike get a complete understanding of how pervasive the costs of gun violence can be.

Simply collecting more data on the economic costs isn’t a replacement for taking more substantive, direct action to reduce gun violence. The available evidence on the immediate human consequences today are clear, and there are current policy prescriptions on the table for enactment.

Both Congress and the Biden administration are offering concrete steps to address the issue. The Bipartisan Safer Communities Act would expand background check requirements, broaden restrictions on gun ownership, and provide incentives for states to pass Extreme Risk Protection Order laws, which allow groups to petition courts to remove weapons from people deemed a threat to themselves or others. Recent executive orders from the Biden administration would increase the number of background checks, accelerate federal law enforcement’s reporting of ballistics data, and provide more information on licensed firearms dealers who violate the law.

These are steps in the right direction, but more can be done. The already available evidence clearly demonstrates the direct human consequences of gun violence on everyday citizens and should spur policymakers into action.

Many policymakers, of course, understand the moral urgency to act to end gun violence. But their knowledge and understanding of the problem can be deepened to create a more holistic understanding of the issue, create more informed evidence-based policymaking going forward, and then have reliable metrics at hand to understand whether and how these policy actions are resulting in better U.S. economic and societal outcomes.