New research documents the high cost of residential racial segregation in Northern cities of the United States

The violent effects of systemic racial segregation are ever-present in U.S. cities today, especially in the big Northern cities that were destinations for Black Americans fleeing racial oppression and violence in the rural American South during the Great Migration. The average Black resident in a Northern metro area today lives in a neighborhood that is at least 50 percent non-White, and most neighborhoods in metropolitan areas where violent crime is the highest are predominantly Black.

Indeed, homicides are the leading cause of death for young Black men in the United States. Young Black men accounted for nearly 40 percent of homicide victims in 2019, the most recent year for which complete data are available, about 20 times higher than young White men. This violence—itself largely borne by Black residents—is the result of decades of institutional racism. It is deeply linked with the history of racism resulting in residential segregation and accompanying “White flight” to the suburbs.

The more widespread consequences of segregation just in Northern American cities are found in rising poverty, collapsing local tax bases needed to maintain high-quality public education and effective public safety, and reduced economic mobility for Black residents. But the most immediate and life-threatening consequence certainly is the tragic rate of homicides.

Documenting this high cost of racial segregation

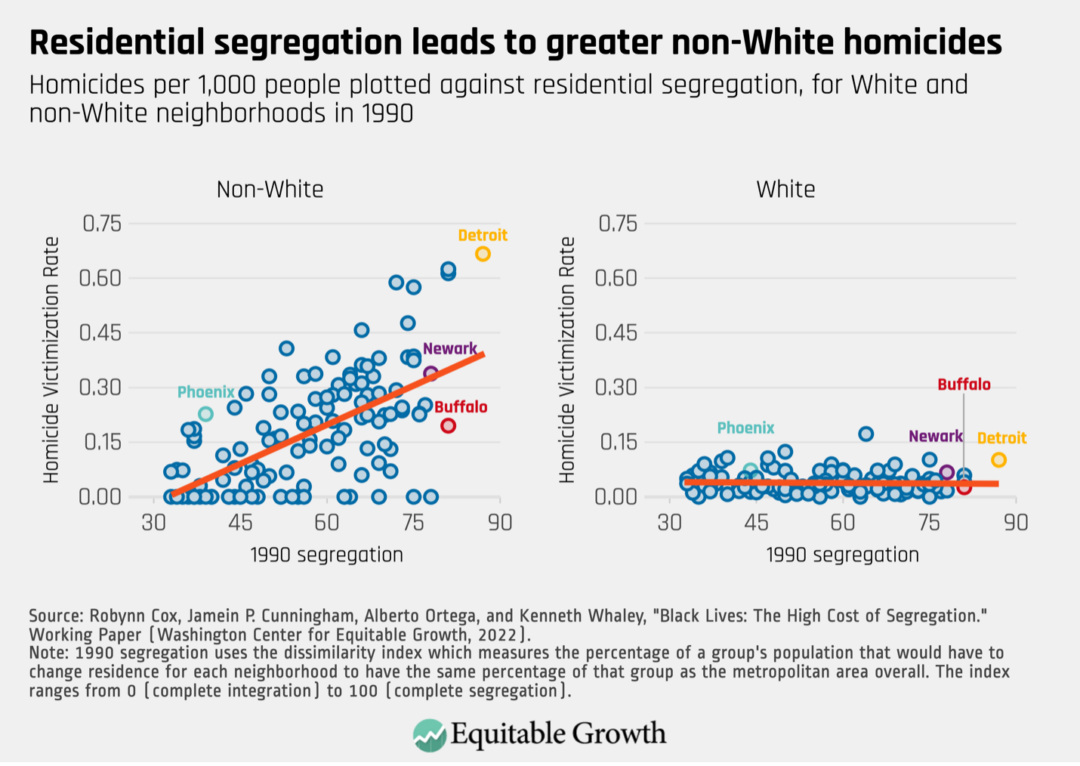

Our new research documents the roots of this tragic consequence—high non-White homicide rates in these highly segregated cities. In our working paper, “Black Lives: The High Cost of Segregation,” we sought to answer how residential segregation affected homicide victimization by race in Northern cities from 1970 to 2010. We find that higher levels of segregation are robustly and positively associated with higher levels of non-White homicide victimization in Northern cities, but unrelated to White homicide deaths.

In order to understand the link between residential racial segregation and crime, we used the configuration of railroad tracks within cities to analyze whether greater levels of segregation could explain higher levels of violent crime. Much of today’s residential segregation (outside of the South) is the result of the first wave of Black migration to the Northern and Western regions of the country between 1910 and 1970, but due to the availability of robust data, our analysis focuses on Northern cities.

We measure residential racial segregation in these cities using a variety of data. We employ the commonly used dissimilarity index applied to every U.S. census from 1970 to 2010. To capture the causal effect of segregation on homicides, we use the configuration of railroad tracks within a city or metropolitan statistical region as our instrumental variable. This variable proxies for the very real “other side of the tracks” idiomatic understanding of the consequences of redlining. Our research samples focus on select Northern cities where a railroad division index is available, and thus it can’t be assumed to apply to all cities. Yet other research suggests these findings would not be unique to these cities.

Our findings are stark. We document a robust causal link between residential racial segregation and the murder rate, and between segregation and non-White homicide victimization. We find that non-White residents bear the burden of violent crime due to segregation, particularly homicides, while finding no effect on White victimization. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Our analysis of the findings points to several reasons residential racial segregation causes non-White homicide rates to be higher in more highly segregated metropolitan areas than in less segregated communities. Segregation lowers local government tax revenues from property taxes, which, in turn, reduces public safety expenditures per capita, including spending on police and fire safety workers. We find that inadequate police employment levels attributed to segregation account for approximately 56 percent of the non-White homicides. The same trend holds true for lower arrest rates for violent and property crimes in highly segregated areas.

These lower tax revenues impact economic mobility in these communities, too. Reduced school expenditures due to segregation are manifested in the negative relationship between segregation and per-pupil spending, which, in turn, inhibits the opportunities of children to benefit from social and economic mobility and drives ongoing inequality in Black communities.

What’s more, lower tax revenues result in disproportionate shifts of the remaining funding toward policing precisely because of higher crime rates in these communities. This more punitive policy approach in response to rising crime leads to higher Black imprisonment rates—yet another consequence of the legacy and the immediate impact of residential racial segregation.

Our new research builds on research showing the effects of residential racial segregation on poverty, inequality, and intergenerational mobility in Black communities, as well as effects of the Great Migration. These findings are similar to Princeton University economist Ellora Derenoncourt’s 2021 working paper, “Can you move to opportunity? Evidence from the Great Migration,” but we isolated the effects of residential racial segregation separate from Black migration. We also focused on metropolitan statistical areas and central cities (rather than the larger area of commuting zones), specific to Northern cities with railroad data.

The steadily accumulated evidence over the past several decades of the harmful consequences of residential racial segregation—particularly the most recent data-driven evidence published in the 21st century—drives home why policymakers at the federal, state, and municipal levels need to move beyond punitive “law and order” policy approaches if they want to address the devastating impacts of violent crime on Black communities.

Conclusion

The use of the pejorative euphemism “inner city” when discussing crime in the United States has been wielded for more than seven decades to stir up fears among mostly White voters that the mostly Black residents of big cities across the country are dangerous and out of control. Such racialized code words are often paired with demands for law and order, and recur in U.S. political campaigns again and again, beginning in the 1960s and replayed in different guises right up to today.

Yet, as we conclude in our new working paper, racial segregation undermines pluralist politics and allows politicians to make budget cuts in Black neighborhoods either because they expect minimal political fallout or to maintain the privileged status of White communities. These disincentives to collective action, in which all Americans have a vested interest in fighting crime in Black communities, remain the most corrosive to our nation’s political debates.

Residential racial segregation is multifaceted and a result of a deep-rooted and complex racial history, where structural racism continues to trap Black Americans in a permanent underclass. Targeted policies that improve socioeconomic conditions and increase opportunities for upward mobility would have long-lasting and persistent effects, decreasing non-White homicides in the long run.

—Jamein P. Cunningham is an assistant professor of economics at the Brook School of Public Policy and the Economics Department at Cornell University. Alberto Ortega is an assistant professor in the O’Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs at Indiana University. Robynn Cox is an assistant professor at the University of Southern California’s School of Social Work. Kenneth Whaley is a lecturer in the Department of Economics at the University of Houston.