Retirement tax incentives supercharge the fortunes of wealthy Americans

Overview

The conventional wisdom is that the nation’s system of retirement tax incentives, built around 401(k)s and Individual Retirement Accounts, is geared at helping the middle class build a small nest egg for their golden years—just enough to supplement Social Security and sustain a modest standard of living after a lifetime of hard work. But as a result of taxpayer abuse and policymaker missteps over decades, tax-advantaged retirement accounts have been hijacked by the rich and their armies of lawyers and accountants. Today, wealthy Americans use tax-advantaged retirement accounts to invest huge sums tax free for themselves and their heirs.

This subversion of retirement tax policy starves the federal government of the resources it needs to make critical investments in physical and social infrastructure that could deliver strong, stable, and broad-based economic growth. In this sudden new era of rising violent authoritarianism abroad and challenges to our own democracy here at home, policymakers need to end these federal tax incentives for the wealthy to demonstrate that the most well-off in our society cannot capture our federal tax system to the detriment of those for whom these retirement savings plans were originally designed.

This issue brief, which was the subject of a panel at the National Institute of Retirement Security’s annual conference earlier this month, presents the evidence for how the growing misuse of the federal tax code by wealthy Americans was engineered and why it matters to average retirement savers and our overall economic health and wellbeing. The brief then concludes with a set of promising policy remedies to help ensure these tax incentives are used by those who need them to save for retirement, not so the wealthy can avoid paying their fair share of taxes when our nation’s needs are high and rising.

The rise of mega retirement accounts for the wealthy

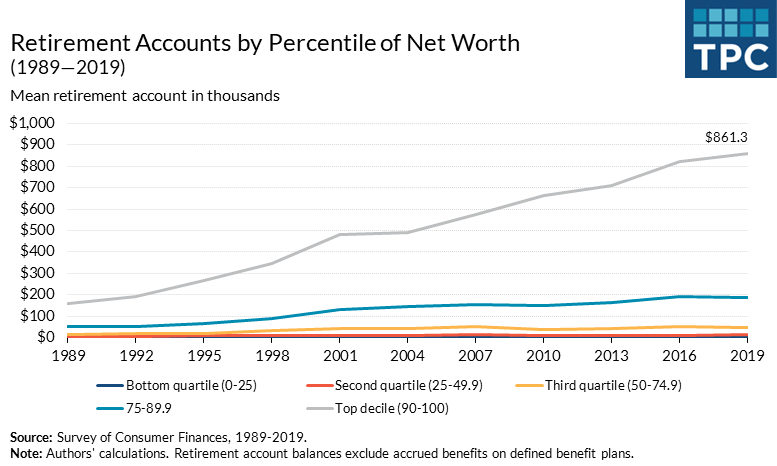

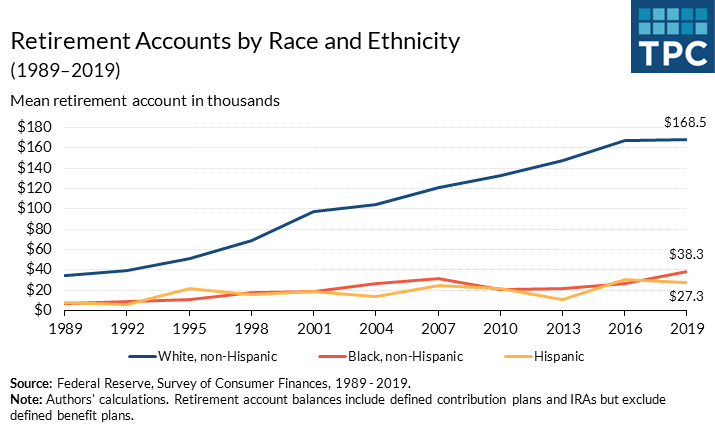

The history of tax preferences for retirement savings, also known as retirement tax expenditures, is long and complex, but the stated desire for these policies has always been to help middle class taxpayers save for retirement. Yet most of these incentives today disproportionately benefit high-income, White Americans. Tyler Bond, the research manager at the National Institute of Retirement Security, shared Figures 1 and 2 below—courtesy of Tax Policy Center Senior Fellow Steven Rosenthal—to make this point at the NIRS conference.

Figure 1

The richest Americans accumulate the largest retirement account balances and corresponding tax benefits

Mean balances for defined contribution retirement accounts, by percentile of net worth, 1989–2019

Figure 2

White Americans accumulate more retirement assets, and receive larger corresponding tax benefits, than Black or Hispanic savers

Mean balances for defined contribution retirement accounts, by race and ethnicity, 1989–2019

This racial divide is the result of systemic discrimination, reflecting decades of policies and practices that denied Black, Latino, and Indigenous Americans access to the best neighborhoods and highest-paying occupations. It is also important to note that the figures above only capture those roughly 60 percent of Americans who have any retirement savings accounts at all—a divergence that itself breaks down along income and racial lines. And, as American University Kogod School of Business professor Caroline Bruckner explained at the NIRS panel, women and gig workers are also likely to have low savings and reduced access to plans, though more and better data are still needed.

For those who do have access, the accounts are increasingly being used as mini hedge funds and tools for intergenerational transfers—one of many rich-friendly carve-outs in the U.S. tax code—by wealthy Americans to avoid taxation and pass on appreciated assets to their heirs tax-free. How do we know this? Thanks to a recent leak of tax records and subsequent reporting by ProPublica, we now know, for example, that the co-founder of PayPal Holdings Inc., Peter Thiel, has a Roth IRA worth roughly $5 billion. Roth IRAs are investment savings plans funded with after-tax money, with all investment gains and withdrawals (after the saver reaches 59.5 years of age) being tax-free.

In contrast, traditional IRAs are funded with pretax money and investments appreciate tax-free, but withdrawals are taxed at ordinary income tax rates. Contributions to both types of accounts are capped. The annual contribution limit in 2021 was $6,000, but the number is adjusted for inflation each year and is reduced for high-income taxpayers. The limits are higher for employer-based defined-contribution plans such as 401(k)s and 403(b)s—$19,500 for employee contributions and $58,000 for total contributions, including employer contributions, in 2021—which can then be “rolled over” into traditional IRAs and Roth IRAs.

Defined-benefit plans also have limits, which tend to be even higher, and most of these plans also can be rolled over into IRAs. The catch with both employer-sponsored defined-contribution plans and defined-benefit plans, though, is that they are highly regulated and are supposed to be provided to all employees at a firm, or at least a large swath of them. IRAs do not face similar constraints.

Thiel’s $5 billion in tax-free retirement savings via a Roth IRA may be an exceptional case, but he is not entirely alone. During his campaign for the presidency in 2012, now-Sen. Mitt Romney (R-UT) disclosed a traditional IRA worth between $20 million and $102 million. The Joint Committee on Taxation estimates that there are roughly 500 taxpayers with IRAs worth $25 million or more, averaging $154 million each.

These 500 exceedingly wealthy individuals—a number of whom were featured in the ProPublica report—are clearly in a league of their own. Yet there are 28,000 more taxpayers with IRAs worth $5 million or more. These so-called mega IRAs add up to roughly $280 billion in total savings.

Providing a tax break for savings well above any reasonable need for consumption in retirement when federal taxes on the wealthy are needed for key investments in the nation makes no sense. Consider this: A $25 million nest egg could guarantee, through a joint-and-survivor annuity, $107,250 of income per month for the rest of a 65-year-old couple’s lives, according to the U.S. Department of Labor’s “Lifetime Income Calculator.”

Instead of actually preparing for retirement, wealthy savers use retirement accounts to shield the sale of appreciated assets from capital gains taxes. Thiel, for example, sold most of his PayPal stock in 2002, and then used the tax-free proceeds to invest in Facebook (now Meta Platforms Inc.). Now, he is able to use his Roth IRA as essentially a tax-free hedge fund to pass on accumulated assets tax-free. Roth IRAs are especially powerful for this type of tax dodge since there are no required minimum distributions during the life of the original account holder, and, until only recently, heirs were able to “stretch” the tax-free build-up of wealth inside the accounts long after the original account holder died.

Mega IRAs, as well as 401(k)s and other workplace plans that have not yet been rolled over to an IRA, cost the U.S. Treasury Department hundreds of billions of dollars in foregone revenue each year. If these accumulated assets were held in normal, post-tax brokerage accounts, they would face capital gains taxes when sold. Given the current top rate on long-term capital gains of 23.8 percent, Thiel’s tax maneuver alone likely cost the U.S. Treasury more than $1 billion.

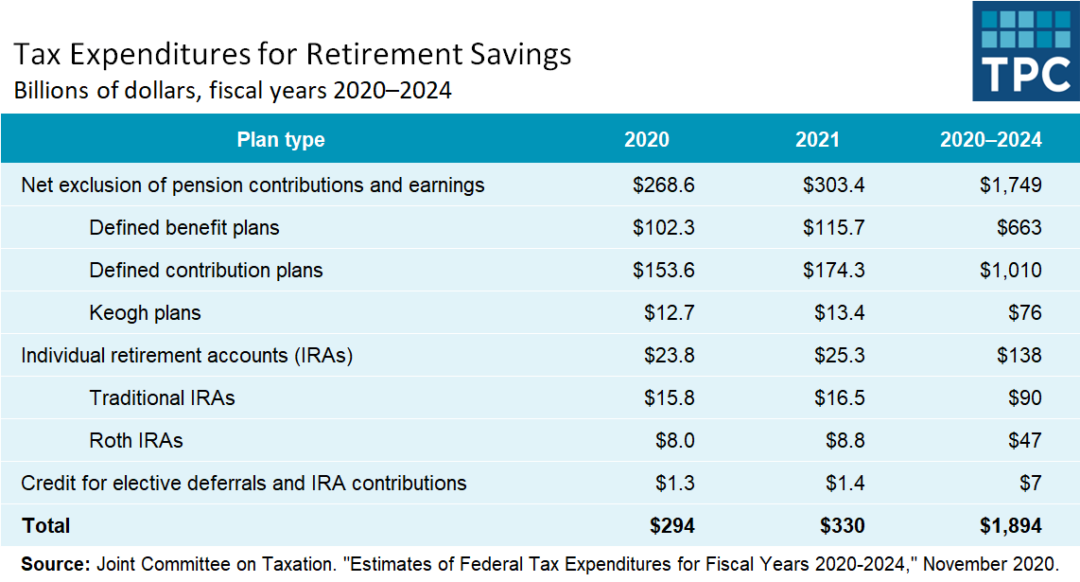

To put that revenue loss in perspective, consider that the federal government provides a bit more than $1 billion per year in the Saver’s Credit, the only retirement tax incentive targeted exclusively at low- and moderate-income Americans. (See Table 1, by the Tax Policy Center.)

Table 1

Retirement tax incentives cost U.S. Treasury hundreds of billions of dollars each year

Estimates of foregone revenue as a result of various retirement tax exclusions, deferrals, and credits, in billions of dollars, 2020–2024

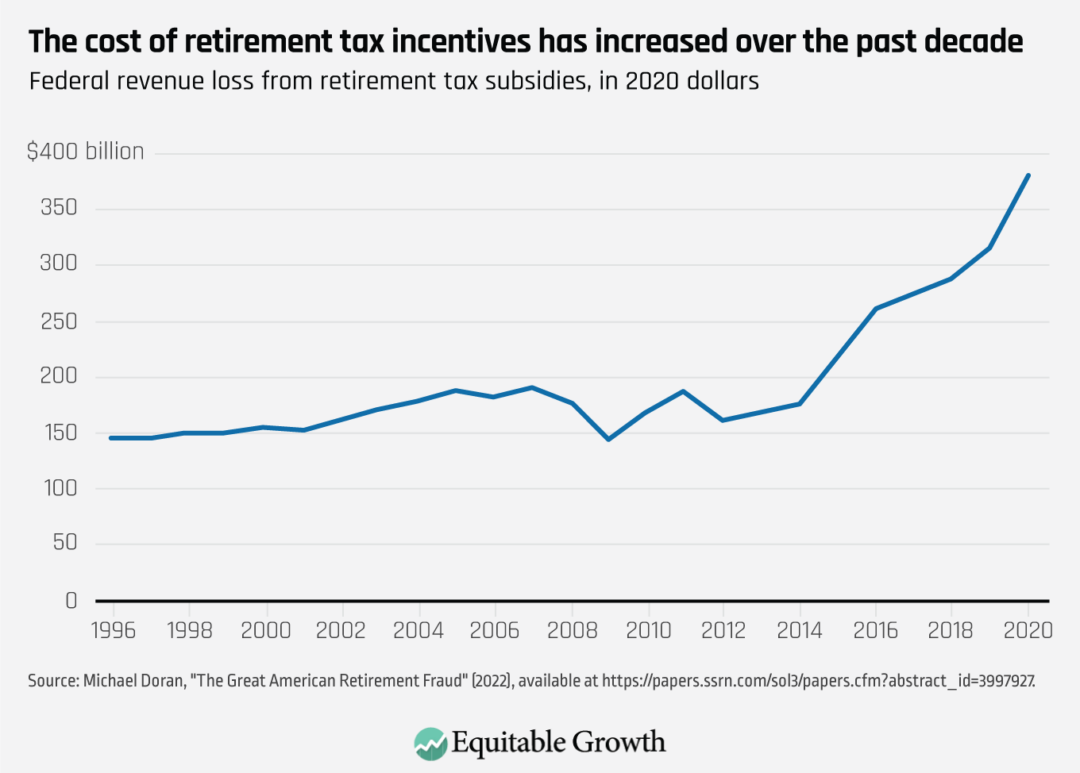

This foregone tax revenue, which has been increasing in constant dollars over the past decade (see Figure 3), could instead pay for critical public investments in physical and social infrastructure that spur equitable economic growth.

Figure 3

(Like Table 1 above, Figure 3 uses Joint Committee on Taxation estimates, but for smoothing purposes Figure 3 uses a 5-year moving average. That is why the $379 billion data point for 2020 in Figure 3 is higher than the $294 billion number in Table 1.)

Tax evasion and other retirement savings policy mistakes

So, how did we reach this highly unfair and inefficient point? How have some savers even been able to build these astronomical balances given the contribution limits referenced above? How have the rich hijacked these accounts that were originally designed for the middle class?

Part of the story is that, like so many other tax evasion schemes, the use of IRAs is underenforced by an underresourced Internal Revenue Service. In Thiel’s case, ProPublica alleges that he used dubious accounting practices to “stuff” a Roth IRA he opened in 1999 with Paypal “founder’s stock,” early equity in the still-private company. He paid one-tenth of one-cent for each share and then watched as the $1,700 account ballooned to 10 figures—all tax-free. ProPublica argues that closer scrutiny of these pricing techniques probably would not have passed muster at the IRS because assets injected into IRAs must be priced at their fair market value.

As for Sen. Romney’s multimillion-dollar IRA, The Atlantic reported that his position at private equity firm Bain Capital before he entered politics enabled him to gain special access to cheap stock in firms before they went public and probably invested his carried interest in certain buyout deals into the IRA. Some of these bets likely did not pay off, but some—such as Domino’s Pizza—did, reported Investment News.

Because these were private companies at the time of the initial investment, it is hard for anybody, including the IRS, to know if the assets were being valued correctly; early financing for speculative ventures will naturally come with somediscount to compensate for the high risk of failure. But because the vast majority of Americans do not have access to these “unconventional assets,” it demonstrates that these accounts, which were designed for middle-income taxpayers, are now bestowing unearned and unjustified benefits onto the rich.

Another part of the story, though, is a series of systematic policy missteps made over a number of years. The most fundamental mistake was building a retirement tax system that gives the largest incentives to high-income individuals already inclined to save a large portion of their income. By letting retirement savers exclude contributions from current taxable income—rather than, say, provide a refundable credit that matches savings dollar-for-dollar—those in higher marginal tax brackets will always receive larger benefits.

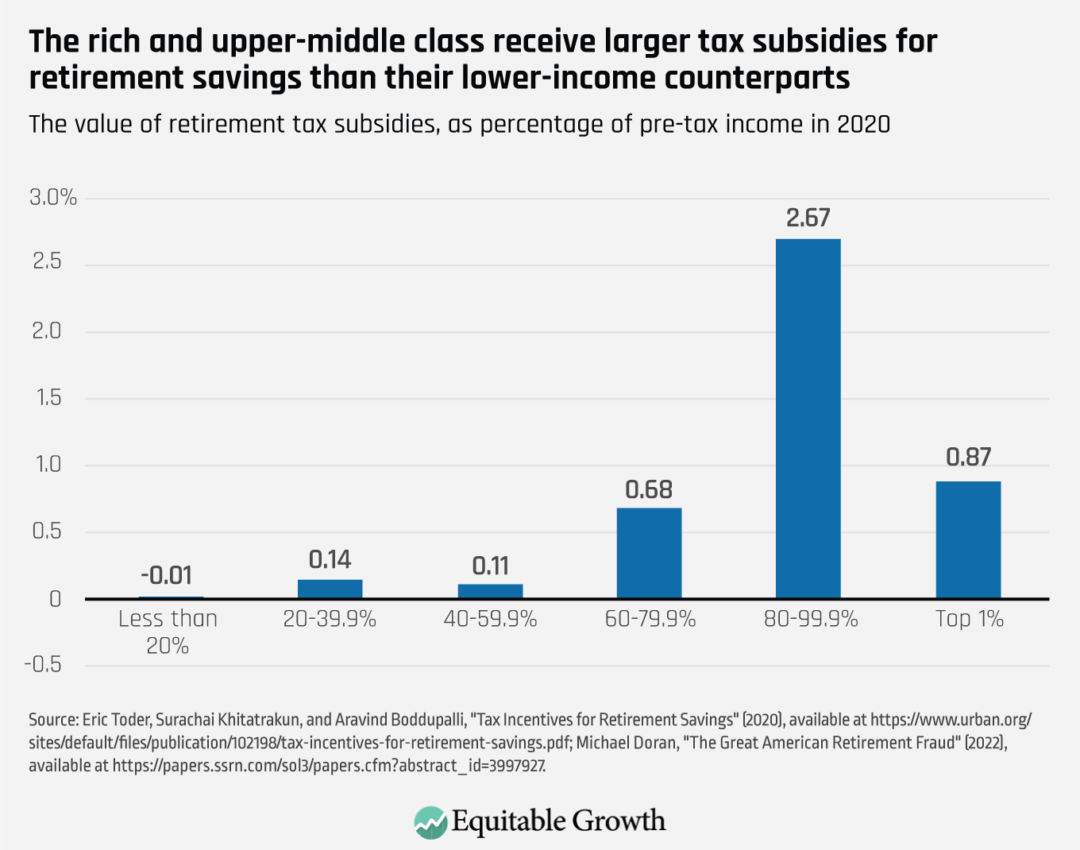

Though there is some debate as to how much newsavings the tax incentives actually encourage, the upside-down, regressive nature of the current system—giving the biggest benefits to those with the highest income—is indefensible. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

As Michael Dolan at the University of Virginia School of Law explains, Congress compounded this design flaw by slowly increasing contribution limits over the past 25 years, part of the deregulatory fervor that took hold across economic policymaking during the neoliberal era. In 1996, for example, Congress repealed the rule that limited the combined amount that employees could save through defined-contribution plans and defined-benefit plans offered by the same employer. This—paired with the rise of cash-balance plans, which are defined-benefit pensions that resemble defined-contribution plans and are increasingly easy for employers to set up for their high-income workers—proved to be an especially costly and regressive policy mistake.

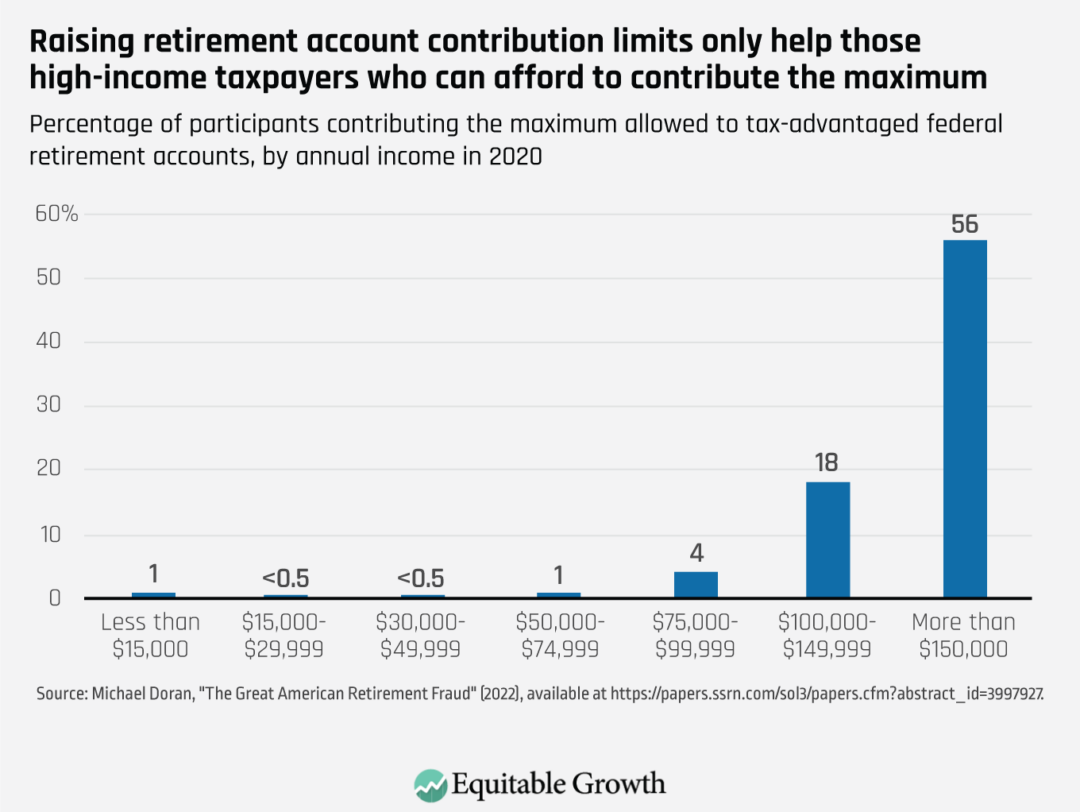

All the while, the nation’s public retirement program, Social Security, saw no major benefit increases as the value of the minimum benefit for low-wage workers—currently $886 per month—declined relative to average wages. Since it is only high-income taxpayers who are ever at risk of hitting up against private retirement contribution limits, increasing the limits is always unduly beneficial to the rich. (See Figure 5.)

Figure 5

Federal legislators have also quietly loosened rules around required minimum distributions from tax-preferred retirement accounts over the years. And, again, these tax policy changes overwhelmingly benefit the well-to-do.

Another damaging set of policy changes by Congress provided taxpayers the chance to “Rothify” their retirement savings. When given this option, many savers will opt to pay taxes now (or during a year when they have low taxable income and are thus in a low marginal tax bracket) in order to avoid paying them later—the distinguishing feature of a Roth IRA. Members of Congress are drawn to this seemingly arcane reform because when taxpayers choose this option, it raises revenue within the 10-year “budget window” that determines how the fiscal effect of a bill is “scored” by budget analysts.

This budget gimmick, which increases revenue on the front-end but is simply traded for reduced revenue on the back-end, was used in 2005 and went into effect in 2010 to create a major loophole that the wealthy’s accountants and lawyers have been all too happy to exploit. They devised ways to make “backdoor” Roth conversions that circumvent rules that are supposed to bar high-income taxpayers from making contributions to a Roth IRA, and even “mega backdoor” Roth conversions, taking advantage of a little-known feature in some 401(k) plans that allow for after-tax contributions well beyond the normal $19,500 limit.

Altogether, these policy changes allow high-income workers to legally game the system. Though they would still be hard-pressed to accumulate Theil-, or even Romney-level, sums in their retirement savings accounts, it has become very possible, as Rosenthal and University of Chicago law professor Daniel Hemel show, for those at the top of the income spectrum, such as lawyers, doctors, and financiers, to shelter multiple millions of dollars over the course of their careers.

Overall, the growth and abuse of retirement tax incentives is a case study in how complexity in the federal tax code built up over many years accrues to the benefit of the rich and well-connected at the expense of everyone else.

Promising developments to return retirement savings incentives to their original purpose

There are a number of members of Congress who recognize these past mistakes and are pushing to reverse course. Here is a rundown of the most promising developments.

Crack down on stretch IRAs

One step in the right direction, as mentioned above, is that heirs to IRAs, until very recently, could use various tactics to keep accounts’ tax benefits flowing indefinitely. In 2019, however, Congress tightened the rules as part of the Setting Every Community Up for Retirement Enhancement, or SECURE, Act, requiring that all inherited IRAs, even Roth-style accounts that are not subject to required minimum distributions, be closed within 10 years.

This reform limits the ability to continually accumulate assets in these accounts tax-free, thus curtailing some of the bequeath-planning benefits of IRAs. (Unfortunately, the SECURE Act also loosened required minimum distribution rules, which cuts in the opposite direction.)

Target the most abusive practices

Policymakers could prohibit the type of IRA stuffing that Thiel and Romney engaged in by simply requiring that IRAs and other tax-advantaged retirement accounts only be used to purchase publicly traded—and thus clearly and fairly priced—securities. This would make no difference to the vast majority of retirement savers who are not rich and connected enough to get access to private equity funds and pre-IPO stocks that turbocharge the IRAs of the uber-wealthy.

Democrats proposed prohibiting these exotic investments from being held in IRAs in an early draft of the Build Back Better Act. But that provision was dropped from the bill before the House passed it, perhaps due to “fierce lobbying resistance.”

Limit Roth IRA conversions

The House-passed Build Back Better Act includes provisions that would prohibit high-income taxpayers from converting a traditional IRA or employer-sponsored plan into a Roth IRA, thus closing down one common way for the rich to shelter investment gains. It would also completely ban the “mega backdoor IRA” that currently allows after-tax contributions to employer-sponsored accounts to be transferred to Roth IRAs.

Limit the total amount of savings that can be held in tax-favored retirement accounts

The House-passed Build Back Better Act also includes a provision that would limit the total amount that could be accumulated in IRAs, 401(k)s, and other defined-contribution employer-sponsored accounts at $10 million for those with incomes of more than $400,000 a year. Those with more than $10 million in those accounts when the provision goes into effect would have to quickly distribute the excess but would not pay tax penalties on forced pre-retirement withdrawals.

This proposal would be simple to administer, though the approach is weaker than what was proposed by the Obama administration, which would have capped combined retirement assets, including defined-benefit plans, at roughly $4 million, or the amount that could deliver a $230,000 per year annuity, which is the current limit for defined-benefit plans. The exact cap under the Obama administration’s proposal would have been different for savers of different ages and also would have taken into account current interest rates, since those factors determine how much savings are needed to purchase a $230,000 per year annuity—a dollar figure that is itself adjusted for inflation each year.

Harmonizing limits across all types of tax-advantaged retirement plans is critical to avoid easy evasion.

Fix and expand the Saver’s Credit

As previously mentioned, the Saver’s Credit is the only retirement tax incentive targeted exclusively at low- and moderate-income families. But it is deeply flawed and, as a result, is extremely underutilized. The credit is also small and limited to a narrow sliver of taxpayers.

Legislators have, for years, proposed expanding the Saver’s Credit and making it refundable. And last year, the idea won bipartisan support as part of a larger retirement policy proposal that also included additional rich-friendly provisions and was included in an early draft of the Build Back Better Act before being stripped out before House passage. Under the latest proposals, the credit would be directly deposited into a taxpayer’s retirement account, giving it the look and feel of a savings “match” rather than a tax refund, perhaps boosting the impact of the incentive.

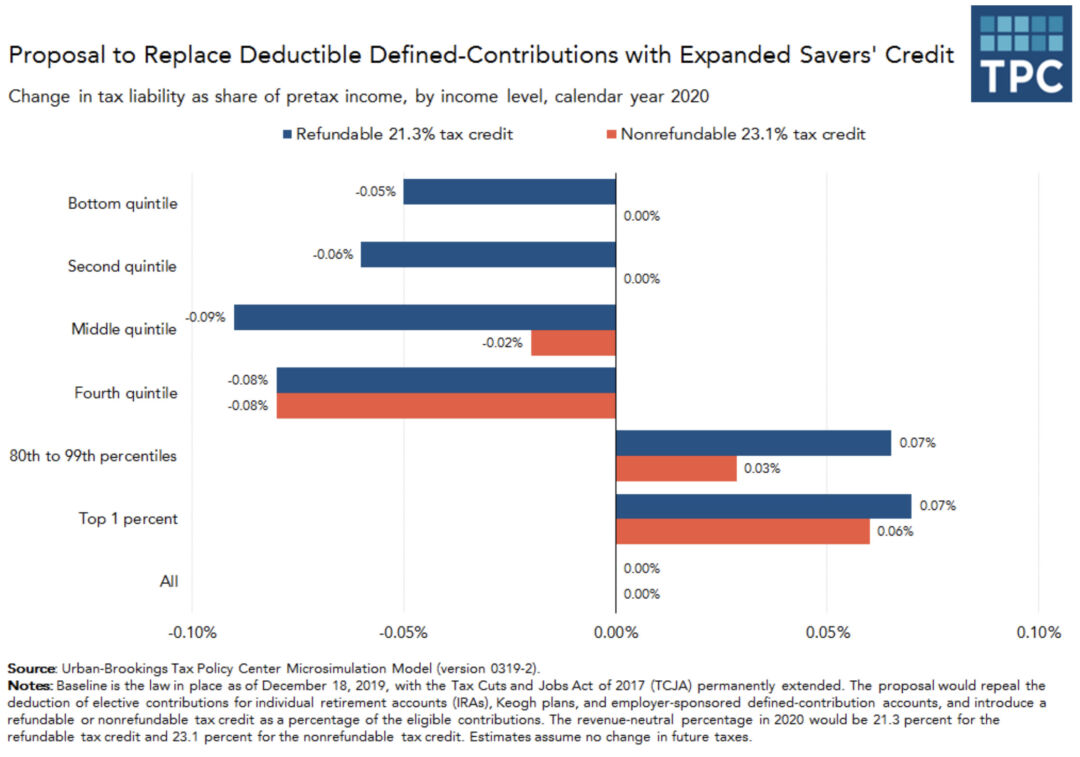

The most important fix, however, would be to make the credit refundable so that those with no income tax liability still get the benefit. (See Figure 6, from the Tax Policy Center.)

Figure 6

Replacing retirement tax deductions with an expanded Saver’s Credit would improve the system’s distributional fairness

Change in tax liability as share of U.S. pre-tax income, by income level, for calendar year 2020

Of course, even if the Saver’s Credit is expanded, low-income taxpayers would still need to know about the credit, find money to save, and, in many cases, open a retirement account on their own—hurdles that are unlikely to be easily overcome.

Expand plan coverage

Though the Saver’s Credit on its own is unlikely to greatly expand retirement security, there are a number of promising ideas for expanding access to employer- or state-sponsored retirement plans. If combined with a reformed Saver’s Credit, or some other government match, then such an approach could have a large impact.

The most exciting development in recent years is the establishment of state-based auto-IRA programs and renewed interest, including from former Trump administration economic adviser (and now vice president of The Lindsey Group and Hoover Institution distinguished visiting fellow) Kevin Hassett, in the idea of opening up federal employees’ Thrift Savings Plan to all workers whose employers don’t already offer a plan. Like the Saver’s Credit, a national auto-IRA plan was included in an early draft of the Build Back Better Act but was taken out before House passage.

Use money from reduced tax incentives to expand Social Security

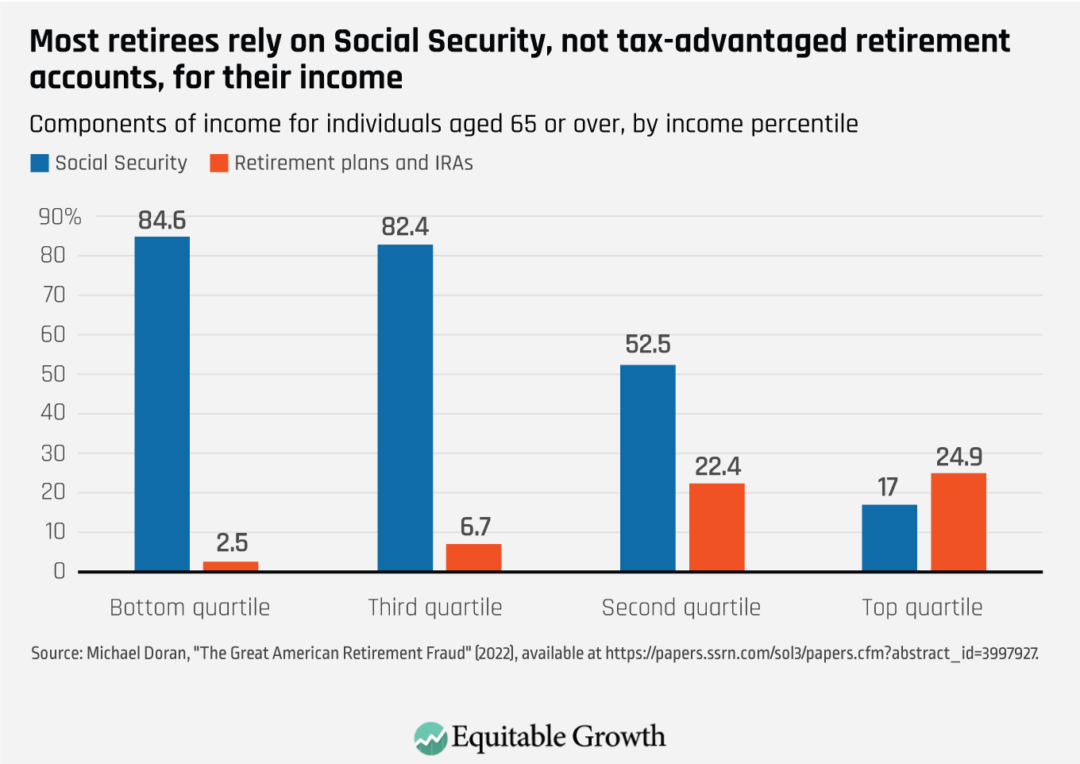

The most effective way to increase retirement security for lower- and middle-income Americans is not a tax deferral or even a revamped tax credit, but rather an expansion of the proven Social Security program. Even with the explosion of tax-preferred retirement savings at the top of the wealth and income ladders documented above, most Americans still rely on Social Security for the vast majority of their retirement income. (See Figure 7.)

Figure 7

There are several ways to shore up and expand Social Security, almost all of which could be funded by reducing the billions of dollars we spend each year on unjustified and wasteful retirement tax incentives.

Conclusion

While there is some reason to be optimistic about the eventual enactment of some combination of these reforms, policymakers have been down this road before. Government watchdogs, consumer-minded advocates, and academic researchers have long identified retirement tax incentives as inefficient and unfair. But getting rid of them has proven extremely difficult.

“Taxing Wealth”

January 28, 2020

Standing in the way is the retirement industry, which includes asset managers, plan administrators, and tax planners, all of whom stand to lose if these retirement system tax breaks go away. And while the wealthy are the biggest winners from these tax subsidies, upper-middle-class savers—a politically powerful constituency in their own right—are heavy users and beneficiaries of the current system. As we’ve seen with 529 college savings accounts and high-value employer-sponsored health insurance plans, taking away tax benefits from this group is politically arduous.

Yet policymakers should feel urgency to enact these reforms. Every year that goes by without action means billions more dollars are socked away in tax shelters or transferred tax-free to heirs rather than invested in critically needed high-return and pro-growth public projects.

—David Mitchell is the director of government and external relations at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth and previously associate director for policy and market solutions at the Aspen Institute Financial Security Program.