What the evidence says and recommendations for future research

Fast facts

Policymakers, regulators, stakeholders, and academics have yet to grapple with the full cross-sectional impacts of hospital mergers. While the evidence is clear that consolidation leads to higher prices in concentrated markets, evidence is mixed on how it impacts the communities in which it occurs, how consolidation affects healthcare providers subject to acquisitions, and how those providers’ patients are affected after mergers are completed. Answers to all these broad questions require further research. Despite these gaps, there is some evidence of the broad consequences of hospital consolidation. Among them:

- The consolidation of hospitals into larger systems can reduce competition, thereby strengthening the bargaining leverage of these hospital systems to command higher reimbursement rates (increased prices).

- When hospital mergers result in higher market concentration and decreased competition among healthcare providers, wages and local economies can suffer. Rural communities are particularly vulnerable to these effects.

- Healthcare providers, specifically nurses and pharmacy workers, are often subject to the negative effects of monopsony power—the power that monopolistic hospitals can exercise in local labor markets with increased market share due to consolidation—resulting in suppressed wages and decreased job mobility.

- Patients’ care options can become limited, resulting in lower quality or restricted geographic availability. Yet mergers also can result in an influx of financial support, leading to new lines of health services, access to a larger network of healthcare providers, and a wider or newer array of technologies for patients.

More evidence is needed to develop policies and models of antitrust enforcement that mitigate the harmful impacts of hospital consolidation while bolstering the positive consequences of these mergers. In areas where evidence is mixed or missing, this report recommends specific topics of investigation to researchers.

Overview

The U.S. hospital market is amid a wave of mergers and acquisitions that first began about 30 years ago and has accelerated steadily since 2010.1 This wave of merger activity, and particularly the recent acceleration in hospital consolidation, is due to various factors, including rising financial instability faced by hospitals, seeking stronger bargaining leverage in the face of increased consolidation in other healthcare sectors, establishing efficiencies and economies of scale, expanding services and care delivery, and a changing healthcare regulatory landscape.

When considering how to address hospital merger activity and its implications, researchers and policymakers alike must look to antitrust leadership and identify scholarship that best informs their work. The Federal Trade Commission is one of two federal antitrust agencies, along with the Antitrust Division of the U.S. Department of Justice, that handle federal antitrust reviews. State antitrust agencies also review hospital mergers for possible anticompetitive effects.

Currently, the Federal Trade Commission is emphasizing understanding of the root causes of unlawful conduct and taking a more interdisciplinary approach in terms of analytical tools and the integration of consumer protection and competition within the agency. This emphasis provides an opportunity for comprehensive analysis outside the scope of legal studies to inform the work of these agencies.

Policymakers, regulators, stakeholders, and academics, however, have yet to grapple with the full cross-sectional impacts of hospital mergers. While the evidence is clear that consolidation leads to higher prices in concentrated markets, evidence is mixed on how it impacts the communities in which it occurs, how consolidation affects healthcare providers subject to acquisitions, and how those providers’ patients are affected after mergers are completed.

Answers to all these broad questions require further research. Despite these gaps, however, there is some evidence of the broad consequences of hospital consolidation. Among them:

- The consolidation of hospitals into larger systems can reduce competition, thereby strengthening the bargaining leverage of these hospital systems to command higher reimbursement rates (increased prices).

- When hospital mergers result in higher market concentration and decreased competition among healthcare providers, wages and local economies can suffer. Rural communities are particularly vulnerable to these effects.

- Healthcare providers, specifically nurses and pharmacy workers, are often subject to the negative effects of monopsony power—the power that monopolistic hospitals can exercise in local labor markets with increased market share due to consolidation—resulting in suppressed wages and decreased job mobility.

- Patients’ care options can become limited, resulting in lower quality or restricted geographic availability. Yet mergers also can result in an influx of financial support, leading to new lines of health services, access to a larger network of healthcare providers, and a wider or newer array of technologies for patients.

More evidence is needed to develop policies and models of antitrust enforcement that mitigate the harmful impacts of hospital consolidation while bolstering the positive consequences of these mergers. In areas where evidence is mixed or missing, this report recommends specific topics of investigation to researchers. This includes answers to questions such as:

- Have there been any changes in the overall economic health of the local healthcare industry due to hospital consolidation?

- What impact has hospital consolidation had on the quality of care that clinicians, including doctors, nurses, and other healthcare professionals, can provide?

- Is there sufficient research on the impacts of hospital consolidation on various demographic populations and disease groups, and how may those activities exacerbate or improve disparities?

- How can policymakers ensure that hospital consolidation does not disproportionately impact vulnerable communities and rural populations?

This report will contribute to the growing body of evidence focused on the implications of increased market concentration of hospitals and health systems by creating an initial landscape of the existing research gaps and opportunities related to hospital consolidation. This report describes and contextualizes, through the market activities of hospitals and health systems, the positive and negative impacts of hospital consolidation on local economies, healthcare providers, and patients after mergers and acquisitions are completed.

In answering these questions, policymakers, stakeholders, and regulators then can appropriately target bad actors in the consolidation process and bolster policies that encourage healthy market dynamics while buffering local communities from any economic ill-effects, preserving provider autonomy and labor opportunities, and improving the quality of care and access for vulnerable patients. The result would be a more effective and efficient U.S. healthcare system, in turn helping ensure more equitable and sustainable economic growth.

U.S. hospital consolidation trends and drivers

The consolidation of hospitals across the United States has been markedly on the rise in the healthcare industry over the past few decades. The available evidence today indicates this consolidation is concentrating hospital markets and reducing competition.

There were 1,519 hospital mergers announced, though not all completed, in the past 20 years, with 680 since 2010.2 Now, more than 90 percent of Metropolitan Statistical Areas—the more than 400 geographic regions of the country associated with a core area of relatively high-density population—are considered highly concentrated for hospitals.3 Most of these areas are dominated by one large health system, such as what we see in Boston (Mass General Brigham), Pittsburgh (University of Pittsburgh Medical Center), and San Francisco (Sutter Health).4

Research also demonstrates that monopoly pricing by hospitals—that is, prices at hospitals with no other hospitals in a 15-mile radius—are, on average, 12.5 percent higher than hospitals with three or more potential competitors nearby.5 Less research has examined the implications beyond price impacts of hospital consolidation and increased hospital market concentration on local economies, healthcare workforces, and patients’ access to healthcare and the quality of that care.

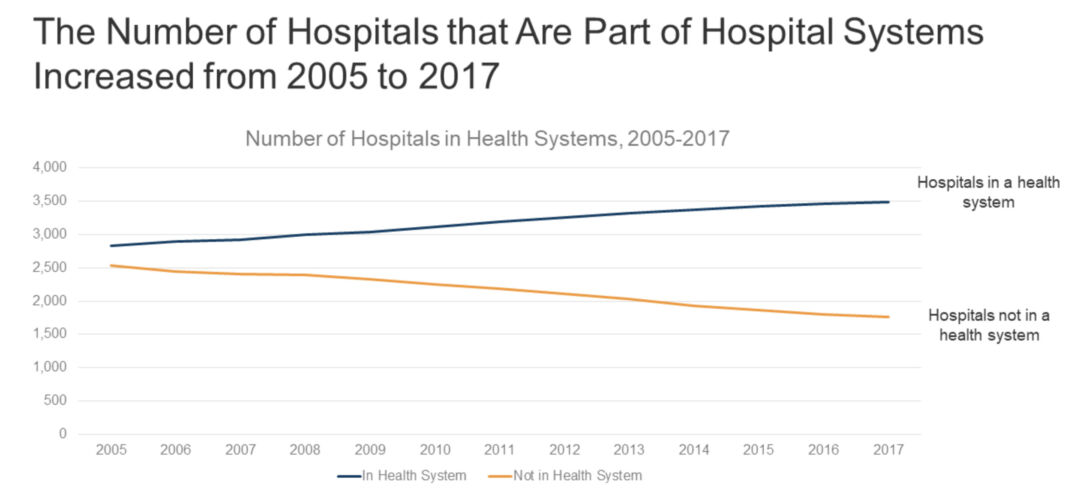

The past decade in particular is marked by significant shifts in how the hospital industry is organized and operates due to mergers and acquisitions of hospitals and independent physician practices and the expansion of monopolistic hospitals and health systems. Since 2010, the number of independent hospitals has declined due to mergers, while the number of hospitals that are part of larger systems has risen.6 (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

As of 2017, 19 percent of markets—representing 11.2 million U.S. residents—were served by only one hospital system.7 These concentrated markets are susceptible to, or have already been impacted by, these shifts in market dynamics and subsequent changes in bargaining leverage exercised by consolidated hospitals and health systems on prices and local labor markets. Numerous studies have already found that consolidation is associated with high healthcare prices. This is important because healthcare prices in the commercial sector drive healthcare spending growth.8

The United States, in 2021, spent $4.3 trillion on healthcare, significantly more than comparable peer nation members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. This spending made up 18.3 percent of U.S. Gross Domestic Product in 2021 while large, wealthy peer countries averaged between 11 percent and 12 percent of GDP and the OECD average was 9.6 percent of GDP.9 This high spending in the United States does not improve the quality of care or access to care, compared to peer countries.10 Of that $4.3 trillion, hospital-related expenses account for $1.3 trillion, or 31 percent of domestic health spending (compared to an average of 28 percent among OECD countries), making up roughly 6 percent of U.S. GDP.11

Considering how consolidation of hospitals and health systems can drive up prices for consumers and their health insurance premiums, studying and addressing the consequences of hospital consolidation is an essential part of containing healthcare spending and protecting healthcare purchasers from increased prices and other consolidation costs related to the quality of care and access to that care.

Two primary types of consolidation in the healthcare sector are the primary focus of academic and policymaker discussions: horizontal and vertical. More specifically:

- Horizontal consolidation refers to mergers among organizations operating at the same level in the healthcare supply chain. This happens when hospitals or health systems merge with other hospitals or when physician practices merge with other physician practices.12

- Vertical consolidation refers to mergers among organizations operating at different levels in the healthcare supply chains. This happens when hospitals and health systems purchase or acquire physician groups, post-acute care facilities, behavioral health services, and other practices in the healthcare supply chain.13 We will not be focusing on this type of consolidation in this report except briefly in the case of the vertical integration of physician groups.

Both forms of consolidation can occur within a single market or across markets, in what are referred to as cross-market mergers. This report primarily focuses on horizontal hospital consolidation between hospitals and health systems, but also touches on the impacts of the vertical integration of physicians into hospitals and health systems as these forms of consolidation often co-occur in markets.14

Hospital consolidation occurs in the United States for several reasons, sometimes in response to external pressures and other times due to internal business and service delivery decisions. Below are brief summaries the five most important drivers of hospital consolidation. While all of these are claimed motivators for consolidating, whether hospitals and systems achieve these intended goals post-merger is yet to be determined.

Financial stability

Consolidation can help struggling hospitals improve their financial stability by reducing operating costs and achieving economies of scale. In this way, a merger can save a hospital or a physician’s practice. According to hospital leaders, the benefits of mergers include cost reductions related to the scale of hospital operations, which allows the dispersal of expenses across a larger patient population, lowers the cost of capital, and provides savings from the standardization of clinical processes.15

Increased bargaining leverage

Consolidation can bolster hospitals’ bargaining leverage with increasingly consolidated health insurance companies. By increasing their bargaining leverage, health systems can secure more favorable contract terms, such as selection by an insurer as a covered provider or higher reimbursement rates.16

Efficiencies and economies of scale

Hospitals affiliated with larger systems can have increased access to shared staff and other administrative resources, helping to lower and spread fixed costs. An American Hospital Association analysis found that hospital acquisitions are associated with a 3.3 percent reduction in annual operating expenses per admission at acquired hospitals.17 Some other industry studies suggest that, depending on implementation, these cost reductions could reach 15 percent to 30 percent due to economies of scale.18

Expansion of services, care delivery, and coordination

Consolidation can allow hospitals to expand their services and offerings to meet the needs of their communities. Post-acquisition analysis shows that 38 percent of acquired hospitals have added at least one service.19 These expansions can lead to improved care coordination and integration of services, resulting in higher-quality patient care.20

Response to changes in regulatory and payment environment

Consolidation can help hospitals respond to changes in the healthcare regulatory landscape, such as the implementation of the Affordable Care Act and other shifts toward value-based payment systems aimed at improving quality and reducing costs, such as shared savings programs, episode-based payments, and global budgeting. By sharing administrative and financial burdens across more sites of care and larger population pools, the hope is to leverage those features to make implementation of policies or participation in programs easier.

How policymakers are responding to hospital consolidation

Several pieces of legislation have been introduced at the federal and state government levels over the past 10 years to promote healthcare competition, correct market distortions, and to ensure the benefits that hospital leaders tout about consolidation are not accompanied by corresponding ill-effects. In 2023 alone, states enacted at least 36 bills across 24 states related to health system consolidation and competition.21 Two of the most significant focus areas at the state and federal levels are:

- Financial and price transparency, which includes state legislative and congressional proposals and state and federal administrative actions to promote hospital price transparency, prevent surprise medical bills, and encourage the shopability of medical services based on prices22

- Antitrust enforcement, includingstrengthening state and federal antitrust laws and enforcement efforts on anticompetitive conduct and efforts to tighten merger oversight in the healthcare sector23

The effectiveness of these measures varies depending on political and economic conditions, the size and scope of the healthcare industry in each market, and the resources available for federal and state enforcement. The next section of this report examines in greater detail what is sparking these legislative and administrative actions.

The consequences of hospital consolidation

The consequences of hospital consolidation are nuanced and depend on various factors, such as certain market characteristics, healthcare provider specialties, and patients’ many and varied characteristics. This section provides an overview of the general effects observed from hospital consolidation. I then more deeply explore what is known about how hospital consolidation affects three particular areas:

- Healthcare labor markets, including the effects on clinicians’ wages, the availability of jobs, and the unique role rural hospitals play in their communities

- Healthcare providers’ professional autonomy, job security, compensation, , the quality of care they can provide to patients, and how nurses exemplify the confluence of consolidation issues affecting all healthcare providers

- The affordability, quality, and accessibility of healthcare services for patients with a spotlight on obstetrics services

Overview of the impacts of hospital consolidation

Before examining the potential downsides of hospital consolidation, it must be acknowledged that consolidation also can deliver considerable benefits. Positive outcomes from hospital consolidation include:

- Financial stability and operational efficiencies. Mergers and acquisitions are tools that some health systems use to keep financially struggling hospitals open by averting bankruptcy or closure. This is in part because newly affiliated hospitals may have more ability to tap into available resources from the system compared to independent hospitals.24

- Increased services. Partnerships, mergers, or acquisitions can help create more cohesive care.25 Research shows that nearly 40 percent of hospitals affiliated with a consolidated health system added one or more services post-acquisition.26 These improvements make it easier for patients to access specialists or services originating in the acquiring system and can help to ensure that care remains in the community.27

- Community engagement. Some researchers observe greater community engagement for system-affiliated hospitals than their independent counterparts.28

Consolidation is not inherently bad, nor should it necessarily be discouraged. What researchers and policymakers need to be concerned about are the negative outcomes that arise from abuses of market power when these hospital mergers and acquisitions occur in already-concentrated markets, leading to further reduced competition. This reduction in competition has been associated with negative consequences, such as increased healthcare prices, lower quality of care, and reduced access to care.29 These impacts are discussed in greater detail later in this report, but let’s briefly detail them here.

Increased prices

The consolidation of hospitals into larger systems can reduce competition and increase concentration, thereby strengthening the bargaining leverage of these hospital systems to command higher reimbursement rates (increased prices) from private payers.

Hospitals and systems with market power resulting from consolidation have greater leverage to raise prices in insurer negotiations.30 Research shows that hospital mergers can increase commercial sector prices by an average of 6 percent, with even more significant price increases in areas with higher market concentration.31

Even when a hospital merges with a hospital in a different geographic area or market (a cross-market merger), evidence suggests there are price impacts. One analysis finds that prices at hospitals acquired by out‐of‐market hospital systems increased by about 17 percent more than their peer unacquired, stand‐alone hospitals.32 A reason for these price increases is that even in a cross-market merger, the hospital has improved its bargaining positions with insurers. Insurers are trying to operate in large geographic areas with large provider networks since it makes them attractive to employers who operate in multiple markets. This large geographic span usually benefits them in negotiations with hospitals, but when the health systems expand their reach, insurers lose their leverage and prices can increase.33

Increased prices for patients also can originate from large hospital systems shifting their patient volume to higher-cost care treatments or facilities.34 For instance, pre-merger or pre-acquisition patients might have been receiving treatment in their local physician’s office, but once the physician is employed by the hospital, they receive their care at a hospital outpatient facility. Their care and their physician have not changed, but the amount insurance or the individual will be billed increases due to the new site of care being a more complex facility than the physician’s office. This is more often brought up as an incentive and driver of vertical consolidation.

Wage stagnation

With healthcare costs rising more rapidly in recent years, there is growing concern that the increase in healthcare spending crowds out wage growth and that hospitals in concentrated markets can use their market power to suppress wages. This has been most clearly studied as it applies to nurses’ wage suppression in concentrated hospital labor markets and will be discussed in greater detail later in this report.35

Closures of hospitals and lines of service

When large health systems acquire hospitals, they may close or eliminate select service lines. Large hospital systems with multiple care sites can shift volume to higher-cost facilities, leading to higher prices.36 Closures also can be based not on community needs but on corporate business considerations that favor other hospitals in their system over the ones they closed. Often, there is little or no local consultation or public input process before hospital consolidations happen.37

Improving or declining quality of care

Evidence is not conclusive or consistent on the association between hospital mergers and the subsequent quality of care. The quality effects of consolidations differ depending on the role of the hospitals in their communities and the measures used to assess that quality, including mortality, readmissions, complications, clinical processes, and patient experiences.38

Increased profits and the use of those profits

Sometimes, consolidation can increase hospital profits as larger healthcare systems achieve operational efficiencies and use their leverage to extract higher prices from insurance company payers and hospital suppliers. Yet the impact of consolidation on hospital profits and savings can vary depending on a range of factors, including the specifics of the merger, the size of the resulting healthcare system, and the local market conditions.39 Research has found that when cost efficiencies are measured, they are modest, at less than 5 percent.40

Importantly, however, evidence suggests that the impacts of hospital consolidation can vary depending on the profit status (for-profit vs. nonprofit) of the hospitals involved. Recent research finds that as market competition decreases, the distribution of Medicaid admissions shifts away from nonprofit hospitals to public hospitals, potentially straining facilities that serve large numbers of uninsured and Medicaid patients.41

Reasons for these differences originate in the priorities and incentives of hospitals based on their financial structures. For-profit hospitals may prioritize financial outcomes and implement cost-cutting measures to improve performance. This can lead to the closure of “underperforming” facilities within the hospitals, such as low-volume obstetrics, and compromise the quality of care.42 The prioritization of finances and centralization of care away from local hospitals can disproportionately affect rural areas where hospitals are already more likely to experience financial challenges or be the sole providers of care.43

Hospital consolidation’s impacts on local labor markets

The study of local labor markets in the United States when discussing hospital consolidation is essential because local hospitals are often one of the largest employers in communities, and changes to their employment patterns can impact their local communities economically. These effects on employment and wages can extend from clinicians to nonskilled labor, and even to those outside the employment of hospitals, through increased healthcare prices and their subsequent impacts on business and household budgets.

The concentration of labor markets as a driver of wage stagnation for certain clinicians is supported by a growing body of evidence, with a documented negative correlation between hospital consolidation and wages.44 This evidence on the consequences of the exercise of labor monopsony by merged hospitals and hospital systems can help inform antitrust authorities as they evaluate mergers and propose regulatory mechanisms to curb consolidation that results in increased market concentration. So, let’s look at the several ways in which local markets are affected by hospital consolidation.

Hospital consolidation suppresses wages and employment of clinicians and other staff

Trends in hospital consolidation have increased concerns about the effects on clinicians’ wages, including physicians, nurses, and other healthcare specialists. While concern spans all specialties and positions, market concentration in the hospital industry has resulted in stagnant or declining wage growth for nurses and pharmacy workers in particular.45 When hospitals increase their share of the local labor market for clinicians, they gain leverage in employee negotiations. This enables some consolidated hospitals to suppress the wages of certain employee groups despite increasing prices.46

These wage effects have been felt more acutely by some clinicians based on their specialty, as previously mentioned, but also based on their geographic location. When looking at merger-wage effects in rural areas, some hospitals have decreased their spending on employee salaries, cutting their budgets by as much as $664,488, or $1,223 per full-time equivalent employee.47 But it is unclear whether these decreases reflect gained efficiencies, changes in staffing mix, or other operational decisions or if they are reflective of the exercise of market power to reduce wages or hours.

In addition to wage effects, consolidation may result in job losses and reduced job security via standard post-merger business activities, such as the integration of administrative functions, the elimination of duplicate positions, and changes in staffing ratios. This can be viewed as a positive from the business side of things if these actions are correcting for financial struggles but are a negative for those workers whose jobs have been reduced or eliminated due to a merger or acquisition.

Hospital consolidation suppresses wages and employment outcomes beyond the healthcare sector

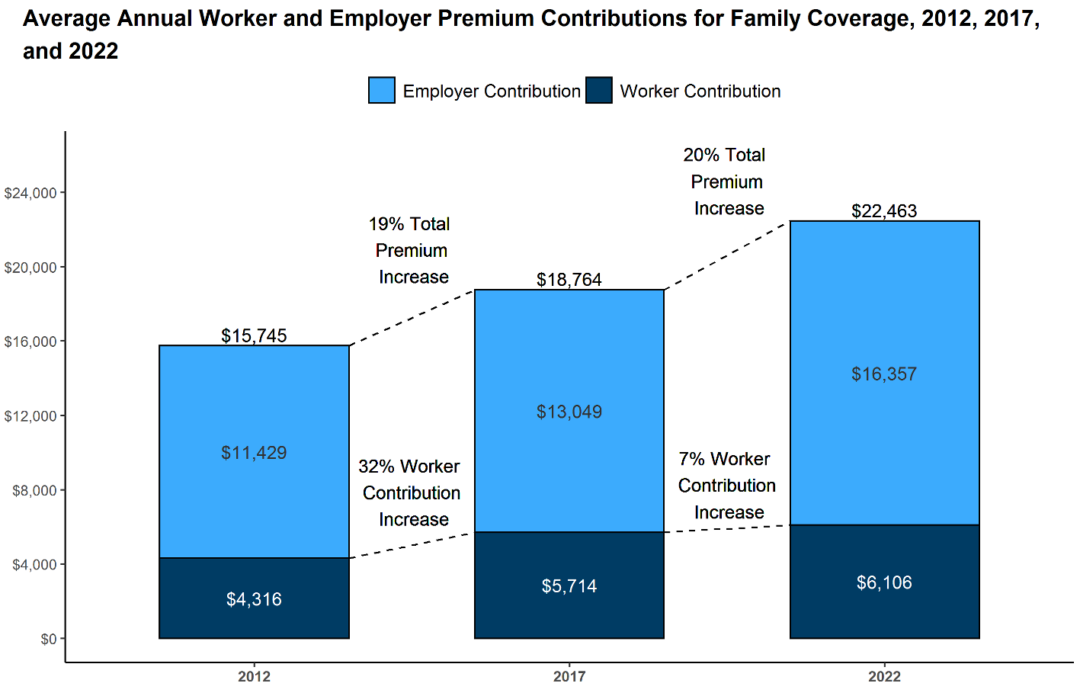

The scale of the hospital sector in the United States is enormous, accounting for $1.3 trillion of healthcare spending and continuing to grow more rapidly than other healthcare sectors, including physician and clinical services and prescription drugs.48 Higher hospital prices impact the local communities they serve economically through the costs of health insurance coverage. More than 150 million U.S. workers receive health insurance benefits from an employer as compensation. The average cost of family coverage has only continued to increase over the past decade. In 2022, it was $22,463 for a family—of that, $6,106 was paid by the worker and $16,357 by the employer.49 (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

There continues to be concern that increased spending on health insurance premiums by employers crowds out wage increases. When employers face increasing healthcare costs, these costs are often covered by increased insurance premiums paid by employees or by a lack of wage growth to offset those expenses.50 These premium price effects are more acutely felt by workers who receive employer-sponsored insurance in a local market where hospital mergers have resulted in a more concentrated market.51 Ultimately, workers are double-dinged when their wages go toward increased premiums and then they become purchasers of higher-priced care in a concentrated hospital market.

Areas in need of further research

As researchers look further into the consequences of hospital consolidation on local economies, they can think about them as internal impacts to the hospitals themselves and external impacts to the communities in which they operate. Take hospital employment practices as an example. As discussed above, hospital consolidation can internally impact hospital employees through employment status or wage changes and then externally impact nonhospital employees through the effects of higher healthcare prices and heftier health insurance premiums.

Further research questions for consideration include where and to whom costs are passed in local markets following hospital mergers, how the consequences in terms of economic growth may vary by market demographics, and if there are trends due to location, particularly any interactions with nearby economically homogenous or affluent areas. Understanding changes to hospital revenue generation pre-and post-merger, and then how profits and capital are used post-merger, needs to be an increasingly integral part of understanding the broader landscape of hospital consolidation. These analyses should factor in market and demographic differences based on population and payer characteristics, such as race, age, income, disease burden, and public vs. private payer mix.

Hospital consolidation’s impacts on healthcare providers

In 2019, there were 22 million workers in the healthcare industry, employing 14 percent of all U.S. workers.76 Given the size and scale of the healthcare sector, the consequences of consolidation on its clinicians and other workers warrant attention by policymakers and researchers. Beyond the impacts on wages discussed above, this section outlines how consolidation affects employment opportunities and job satisfaction among hospital staff. These factors can significantly impact the quality of care and subsequent patient outcomes, making it critical to address the potential consequences of hospital consolidation.

Physicians

The trend toward consolidation affects physicians as they are subject to ownership changes at hospitals they already work for or end up encouraged to vertically consolidate their practices with hospitals and health systems. While this report has thus far focused on the horizontal consolidation of hospitals and their impacts, the story of hospital consolidation would not be complete without a brief discussion of the vertical consolidation of healthcare providers—particularly physicians—and their subsequent experiences in merged hospitals and health systems.

The vertical consolidation of physicians into hospitals and systems has increased in the past decade, with 2016 being the first year in which fewer than half of practicing physicians (47.1 percent) had an ownership stake in their practice, and with 2018 marking the first year in which there were fewer physician owners (45.9 percent) than employees (47.4 percent).77

This decline in physician ownership will continue as more physicians become vertically integrated or employed by hospitals or health systems. This trend has significant implications for the healthcare industry, as physicians employed by hospitals may be subject to different incentives, priorities, and administration burdens and barriers than those who are self-employed or part of smaller practices.

Unfortunately, our understanding and evidence of clinician well-being and job satisfaction mostly come from convenience samples and surveys from voluntary hospitals and health systems, and often from only physicians or only nurses. Even with those measurement challenges, we should pay some attention to the impacts of hospital consolidation on clinician job satisfaction, as burnout and job dissatisfaction can lead to poor patient outcomes and exacerbate clinician shortages.78

It is also worth noting that while not formally investigated yet, all these effects of consolidation on physicians may be compounded by the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Evidence shows that the pandemic decreased job satisfaction among healthcare providers.79 It also decreased employment, with hundreds of hospital-based physicians experiencing furloughs or layoffs when elective surgeries were paused, causing procedural and revenue decreases for hospitals and health systems.80 The COVID-19 pandemic may spur additional research in this space at a time when evidence and policy are greatly needed.

Nonclinical hospital staff

The impact of hospital consolidation on all hospital staff, including nonclinical staff, is crucial for evaluating the broader implications of consolidation in the healthcare industry and local economies, where health systems can comprise a large portion of employment.

Nonclinical staff are more insulated from the impacts of hospital consolidation

As previously discussed, hospital consolidation can impact staffing levels and thus job security, compensation and benefits, and the overall work environment. But nonspecialized workers, such as custodians, food-service workers, and security guards, are less likely to be affected by a merger since their skills are transferable to employers in other sectors, assuming availability in their local market and that the hospital is not the dominant employer in their field of work.81 Excluding that dominant-employer scenario, hospital consolidation has not been found to depress the wages of general or blue-collar workers whose skills are not industry specific.82

However, while nonclinical staff may be protected from wage effects, their job satisfaction and subsequent responses may still be positively or negatively impacted by consolidation, similar to clinical staff, when there are changes to workloads or processes.83 For this reason, further inclusion of all hospital employees in impacts analysis is needed.

Ultimately, hospitals are in the business of providing care, so studying and understanding the consequences of hospital consolidation on the individuals they employ to provide that care is important. Questions for consideration include how the availability of resources and support for clinicians changes pre- and post-merger, how autonomy changes and then affects clinical care decisions, and whether changes in caseloads impact care delivery and job satisfaction.

Regarding the clinician-patient relationship and how hospital consolidation can affect it—with a particular eye on issues of health equity and clinician diversity—researchers should investigate the impacts on continuity of care under ownership changes and the availability of specialists and clinicians of diverse backgrounds.

Hospital consolidation’s impacts on patients

Much of the discussion in academic literature and among policymakers has focused on the impact of consolidation by way of induced price increases on household budgets while placing the patient at the periphery instead of the center of the issue. A reason for this divorce in focus lies in the difficulty of measuring how hospital consolidation and market concentration can impact patients’ quality of care and access to that care.

Despite this challenge, some compelling research does examine patients’ quality of care and access to care. So, let’s briefly look at what evidence is available on the effects of prices and then on quality and access for patients to demonstrate this area is ripe for further investigation.

Prices

The growth in hospital prices is the major driver of healthcare spending growth in the commercial sector, and healthcare spending consumes a growing share of U.S. individual and family budgets, leaving less to spend on other necessities.100 Additionally, as previously discussed, rising healthcare spending is associated with wage stagnation, compounding the issue of rising expenses with reduced or suppressed income.101 This combination of increased costs and the stress it produces on families’ budgets and well-being makes it necessary to examine both the household effects of rising prices on patients and the care outcomes they are often over-paying for.

Increased prices after hospital mergers in concentrated markets do not always result in improved mortality or investment in care

Understanding the interplay between prices and the quality of care in hospitals has proven to be a moving target for researchers to measure, given the difficulty of controlling for external influences on outcomes and how that in turn factors into the creation of quality measures.

Higher nominal prices are not necessarily bad when patients get more value for their money in the form of improved outcomes, more easily measured in the form of mortality rates. The question of whether higher priced care is better care remains unclear, but in cases where improvements in mortality rates are gained at higher-priced hospitals, it only holds true in less concentrated markets. This could be in part because the increased spending to deliver a higher quality of care would help a hospital distinguish itself from competitors. In concentrated markets, research shows no effect on mortality, even when spending increases.102 It is not always clear what this spending goes toward and it may not be on activities that increase outcomes in the absence of a competitor to compete with on quality.

Hospitals’ increasing spending without measurable improvements indicates a broken market where hospitals should compete on costs and quality. When hospitals no longer need to compete on that basis, their incentives to provide higher-quality care or invest in innovations and technologies can be affected. This can manifest as decreased financial investment in low-profit-generating initiatives, such as quality improvement or social determinants of health interventions.103

Quality and access

Hospital consolidation in the United States has complex and multifaceted effects on the quality of care. There is a growing body of mixed evidence on the impacts of care pre- and post-merger, demonstrating the complexity in capturing quality impact.104 Factors such as the specifics of the consolidation, the size of the resulting healthcare system, types of hospital units effected, and changes over time all contribute to these varied outcomes that require further exploration.

Acquired hospitals may benefit from increased resources offered by their new system improving patient access and choice

Mixed evidence suggests consolidation can lead to improved coordination of care, better management of complex medical conditions, and reduced readmissions, contributing to enhanced quality of care. In many cases, though, a positive action can eventually lead to a negative outcome, so discerning where in the process of consolidation and market concentration the issue arises can help better target policy and regulation.

For example, integration of healthcare institutions can advance the dissemination of best practices and treatments, improving hospital performance and patient outcomes.105 However, increased network communication and shared learning does not always mean the “best” practices are being disseminated or encouraged. Following this thread, we see evidence that consolidation into large healthcare systems within highly concentrated markets can lead to overtreatment. This is due to the lack of competition creating financial incentives to recommend unnecessary tests and procedures.106 In addition to the concerns around the quality of care associated with unnecessary and low-value services, this also has negative implications for healthcare spending through overutilization.

On the flip side, when actual best practices are shared, mergers and acquisitions of physician partnerships help improve access to care for patients in rural and underserved communities.107 These mergers can enable hospitals to expand service offerings, broaden provider and specialist networks, and better serve patients in their local communities.108

Quality of care after hospital consolidation is not sufficiently studied, especially among specific patient groups and geographies

While there may be some efficiency benefits from mergers and acquisitions, the impact on patient outcomes, particularly for different disease groups, should be central to any discussion. Research has yet to demonstrate the definitive benefits of consolidation via improved quality.

Given their complexity and vulnerability to noise, analyses of quality measures tend to be narrowly focused on geographies, disease groups, or other populations where variables can be better controlled for. For instance, researchers find a decrease in mortality among patients staying in the hospital for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, stroke, and pneumonia post-merger at merged rural hospitals, compared to those that did not merge.109 While this evidence is great, it is limited to those diseases and rural hospitals. These nuanced studies are important to understanding the full scale of impacts, but many more are needed to build the evidence base.

When quality is studied post-merger in a broader population, often those studies are older in origin and there are little to no improvements found and, in some cases, there are worse outcomes or changes in practice patterns that are associated with worse or unnecessary care. For example, mergers in California between the years of 1990 and 2006 have been shown to increase the likelihood of intensive surgery and the total number of surgeries performed while not improving patient outcomes.110

Another outdated study in need of a refresh tracks Medicare patients who had heart attacks between 1985 and 1994 in more concentrated markets, finding that their risk-adjusted 1-year mortality rate was 4.4 percent higher, compared to those patients in less concentrated markets.111 Both of these studies demonstrate the valuable evidence that can be generated from these analysis on consolidation impacts on quality and highlight the need for more.

On a final note, consolidation also is associated with a small decline in patient experience measures.112 While these experience measures are not of as high importance as others such as mortality outcomes and are self-reported patient experience can still serve as a metric for overall hospital performance.

Recommended future research

All stakeholders in the U.S. healthcare system, including patients, healthcare providers, payers, and policymakers, need to consider how to maintain or create competitive markets that produce high-quality and equitable care. This requires evidence on the full scope of effects of hospital consolidation on pricing and the quality of care and access to care.

As put forth in this report, there are several detailed questions that must be considered and answered. This includes considering hospital consolidation that occurs within and outside of concentrated markets as the impacts can be expected to vary in more concentrated versus less concentrated markets. Longitudinal approaches would also be beneficial applied to all the areas of research outlined below.

How can we better estimate the local economic impacts of consolidation beyond price and wage effects?

While the price effects of consolidation are known, taking these analyses further to explore how they impact specific populations or market subsects and under different payer mixes would be extremely valuable in developing public and private payment policies and systems of integrated care. Specifically:

- To whom and in what proportion are the price increases following hospital consolidation passed on to insurers, patients, employers, or taxpayers?

- How can antitrust policymakers better estimate the local economic impacts of consolidation beyond the effects on prices and wages?

- Does consolidation reduce or encourage economic growth? Does this vary by market or population characteristics?

- Are consolidation and increases in market concentration more likely to occur in economically, racially, geographically, or culturally homogenous areas, compared to heterogenous communities?

- How are increases in capital or profit used post-merger? Can subsequent correlations be identified in terms of wider economic or community benefits?

What impact does hospital consolidation have on clinicians’ abilities to provide quality care?

As previously discussed, capturing the experiences of clinicians is already difficult without adding the lens of consolidation to the analysis. But there is room for improvement and pertinent questions to be contemplated, which would be helpful in the development of thoughtful policy and regulations related to hospital consolidation. Specifically:

- Does hospital consolidation lead to changes in the availability of resources and support for clinicians?

- Does hospital consolidation affect the autonomy of clinicians in making clinical decisions?

- Do clinicians experience changes in workload or patient caseloads?

- Do clinicians experience changes in the continuity of care or relationships with their patients due to hospital consolidation?

- What is the clinician’s perspective on the job market and opportunities for their specialty pre- and post-merger?

- Are there trends in specialist employment or geographic relocation of specialists following mergers or acquisitions? Are these associated with any patterns of clinician shortages?

- What is the uptake of new technologies that enhance clinician reach in hospitals pre- and post-merger or compared to independent hospitals?

How does hospital consolidation affect access to care and the quality of care for patients?

Measuring health outcomes is difficult, yet attempts to understand the consequences of hospital consolidation on specific demographics and disease groups are essential to building safeguards and targeted solutions into policies and regulations. In particular, the extent to which hospital consolidation contributes to disparities in access to healthcare for disadvantaged and minority populations remains unexplored. Specifically:

- Does consolidation reduce or expand locations or specific services more often than others? Are there trends where these service lines are affected?

- What impact does hospital consolidation have on the ability of patients to make healthcare decisions that align with their personal preferences and values?

- What are the impacts of patient access to culturally competent providers of varying demographics, such as age, race, languages, and gender?

- Does reduced competition and increased market concentration of hospitals worsen or improve financial barriers to care for minority and rural populations?

- Does consolidation exacerbate or remove barriers to geographic access to care?

Conclusion

Patients must rely on the hospital sector when they are most vulnerable, such as during acute illnesses, major injuries, or giving birth. In addition to being essential providers of care, hospitals are large employers with far-reaching impacts in their communities. Given their importance, policymakers and researchers must do more to understand the underlying causes of hospital consolidation and mitigate the potential negative impacts of hospital concentration in noncompetitive markets.

A healthy healthcare ecosystem is essential for patients and critical to the healthcare workforce and local economies. By prioritizing the preservation of competition, transparency of merger and acquisition activities, and equitable access to care, policymakers and researchers can help create a healthcare system that benefits all stakeholders and improves health outcomes for all patients.

About the author

Amy Phillips is a policy analyst for markets and competition policy at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth. Her areas of focus include hospital consolidation, healthcare market competition, health equity, and healthcare pricing and payment. Prior to joining Equitable Growth, she was a graduate fellow at Sirona Strategies, where she worked on two healthcare coalitions focused on acute care in the home and social determinants of health. Phillips also conducted health policy research in the office of Rep. Lloyd Doggett (D-TX) focused on telehealth and Medicare policy. She also served as the healthcare chief of staff at Arnold Ventures and was a research assistant at the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, conducting research on a wide range of Medicare payment policy issues. Phillips received her Master of Public Affairs from the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin and her B.A. in medical anthropology from the University of Pennsylvania.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Arnold Ventures. The Washington Center for Equitable Growth maintains full editorial control over all of its self-published pieces.

End Notes

1. Nancy D. Beaulieu and others, “Changes in Quality of Care After Hospital Mergers and Acquisitions,” New England Journal of Medicine 382 (1) (2020): 51–59, available at https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMsa1901383.

2. Martin Gaynor, “Examining the Impact of Health Care Consolidation,” Testimony before the Committee on Energy and Commerce, Oversight and Investigations Subcommittee, “Examining the Impact of Health Care Consolidation,” February 14, 2018, available at https://ssrn.com/abstract=3287848.

3. Brent D. Fulton, “Health Care Market Concentration Trends in the United States: Evidence and Policy Responses,” Health Affairs 36 (9) (2017): 1530–1538, available at https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0556.

4. Gaynor, “Examining the Impact of Health Care Consolidation.”

5. Zack Cooper and others, “The Price Ain’t Right? Hospital Prices and Health Spending on the Privately Insured,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 134 (1) (2019): 51–107, available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7517591/.

6. Karen Schwartz and others, “What We Know About Provider Consolidation” (Washington: Kaiser Family Foundation, 2020), available at https://www.kff.org/health-costs/issue-brief/what-we-know-about-provider-consolidation/.

7. Garret Johnson and Austin Frakt, “Hospital Markets in the United States, 2007-2017,” Healthcare 8 (3) (2020): 100445, available at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2213076420300440.

8. Cooper and others, “The Price Ain’t Right? Hospital Prices and Health Spending on the Privately Insured”; Health Care Cost Institute, “Health Care Cost and Utilization Report” (2019), available at https://healthcostinstitute.org/images/easyblog_articles/276/HCCI-2017-Health-Care-Cost-and-Utilization-Report-02.12.19.pdf.

9. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “National Health Expenditures Fact Sheet” (2023), available at https://www.cms.gov/data-research/statistics-trends-and-reports/national-health-expenditure-data/nhe-fact-sheet; Murina Z. Gunja, Evan D. Gumas, and Reginald D. Williams II, “U.S. Health Care from a Global Perspective, 2022: Accelerating Spending, Worsening Outcomes” (Washington: Commonwealth Fund, 2023), available at https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2023/jan/us-health-care-global-perspective-2022.

10. Gerard Anderson, Peter Hussey, and Varduhi Petrosyan, “It’s Still the Prices, Stupid: Why the US Spends So Much on Health Care, and a Tribute to Uwe Reinhardt,” Health Affairs 38 (1) (2019): 87–95, available at https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05144; Sean P. Keehan and others, “National Health Expenditure Projects, 2022-31: Growth to Stabilize Once the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency Ends,” Health Affairs 42 (7) (2023): 886–898, available to https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2023.00403; The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, “Tackling Wasteful Spending on Health” (2017), available at https://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/Tackling-Wasteful-Spending-on-Health-Highlights-revised.pdf.

11. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “National Health Expenditures Fact Sheet” (2023); The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, “Tackling Wasteful Spending on Health.”

12. Schwartz and others, “What We Know About Provider Consolidation.”

13. Ibid; Jodi L. Liu and others, “Environmental Scan on Consolidation Trends and Impacts in Health Care Markets” (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2022), available at https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1820-1.html.

14. Leemore Dafny, Kate Ho, and Robin S. Lee, “The Price Effects of Cross-Market Mergers: Theory and Evidence from the Hospital Industry,” RAND Journal of Economics 50 (2) (2019): 286–325, available at https://doi.org/10.1111/1756-2171.12270.

15. Monica Noether, Sean May, and Ben Stearns, “Hospital Merger Benefits: Views from Leaders and Econometric Analysis – An Update” (American Hospital Association and Charles River Associates, 2019), available at https://media.crai.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/16164319/CRA-report-merger-benefits-2019-FINAL.pdf; American Hospital Association, “Partnerships, Mergers, and Acquisitions Can Provide Benefits to Certain Hospitals and Communities” (2021), available at https://www.aha.org/standardsguidelines/2021-10-08-partnerships-mergers-and-acquisitions-can-provide-benefits-certain.

16. Gaynor, “Examining the Impact of Health Care Consolidation.”

17. Noether, May, and Steams, “Hospital Merger Benefits: An Econometric Analysis Revisited.”

18. Anil Kaul, K.R. Prabha, and Suman Katragadda, “Size Should Matter: Five Ways to Help Healthcare Systems Realize the Benefits of Scale” (London: PwC, 2016), available at https://www.strategyand.pwc.com/us/en/reports/2016/size-should-matter.pdf.

19. American Hospital Association, “Partnerships, Mergers, and Acquisitions Can Provide Benefits to Certain Hospitals and Communities.”

20. Ibid.

21. “Health Costs, Coverage and Delivery State Legislation,” available at https://www.ncsl.org/health/health-costs-coverage-and-delivery-state-legislation (last accessed September 22, 2023).

22. “Key Initiatives: Hospital Price Transparency,” available at https://www.cms.gov/priorities/key-initiatives/hospital-price-transparency (last accessed September 6, 2023); “No Surprises Act: Ending Surprise Medical Billing,” available at https://www.cms.gov/nosurprises (last accessed September 15, 2023); The Health Care Price Transparency Act of 2023, H.R. 4822, U.S. House Committee on Ways & Means, available at https://waysandmeans.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/HR-4822-Section-Summary.pdf.

23. “Health Care Competition: The FTC’s Health Care Work,” available at https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/topics/competition-enforcement/health-care-competition (last accessed October 31, 2023); The White House, “Fact Sheet: Executive Order on Promoting Competition in the American Economy,” July 9, 2021, available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/07/09/fact-sheet-executive-order-on-promoting-competition-in-the-american-economy/.

24. Nathan W. Carroll, Dean G. Smith, and John R.C. Wheeler, “Capital Investment by Independent and System-Affiliated Hospitals,” INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing 52 (2015): 1–9, available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/26369603.

25. American Hospital Association, “Hospital Mergers and Acquisitions Can Expand and Preserve Access to Care” (2023), available at https://www.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2023/03/FS-mergers-and-acquisitions.pdf.

26. American Hospital Association, “Partnerships, Mergers, and Acquisitions Can Provide Benefits to Certain Hospitals and Communities.”

27. American Hospital Association, “Hospital Mergers and Acquisitions Can Expand and Preserve Access to Care.”

28. Jeffrey A. Alexander and others, “How Do System Affiliated Hospitals Fare in Providing Community Benefit?” INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing 46 (1) (2009): 72–91, available at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.5034/inquiryjrnl_46.01.72.

29. Thomas Koch, Brett Wendling, and Nathan E. Wilson, “Physician Market Structure, Patient Outcomes, and Spending: An Examination of Medicare Beneficiaries,” Health Services Research 53 (5) (2018): 3549–3568, available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6153168/.

30. Schwartz and others, “What We Know About Provider Consolidation.”

31. Dafny, Ho, and Lee, “The Price Effects of Cross-Market Mergers: Theory and Evidence from the Hospital Industry.”

32. Matthew S. Lewis and Kevin E. Pflum. “Hospital Systems and Bargaining Power: Evidence from Out-of-Market Acquisitions,” The RAND Journal of Economics 48 (3) (2017): 579–610, available at https://doi.org/10.1111/1756-2171.12186.

33. Gaynor, “Examining the Impact of Health Care Consolidation”

34. Ibid.

35. Elena Prager and Matt Schmitt, “Employer Consolidation and Wages: Evidence from Hospitals,” American Economic Review 111 (2) (2021): 397–427, available at https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.20190690.

36. Gaynor, “Examining the Impact of Health Care Consolidation.”

37. Jane Wishner and others, “A Look at Rural Hospital Closures and Implications for Access to Care: Three Case Studies” (Washington: Kaiser Family Foundation, 2016), available at https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/a-look-at-rural-hospital-closures-and-implications-for-access-to-care/.

38. Ryan L. Mutter, Patrick S. Romano, and Herbert S. Wong, “The Effects of US Hospital Consolidations on Hospital Quality,” International Journal of the Economics of Business 18 (1) (2011):109–126, available at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13571516.2011.542961.

39. Cory Capps, David Dranove, and Christopher Ody, “The Effect of Hospital Acquisitions of Physician Practices on Prices and Spending,” Journal of Health Economics 59 (2018): 139–152, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2018.04.001.

40. Stuart Craig, Matthew Grennan, and Ashley Swanson, “Mergers and Marginal Costs: New Evidence on Hospital Buyer Power,” RAND Journal of Economics 52 (1) (2021): 151–178, available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/1756-2171.12365.

41. Sunita M. Desai and others, “Hospital Concentration and Low-Income Populations: Evidence from New York State Medicaid,” Journal of Health Economics 90 (2023): 102770, available at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0167629623000474.

42. Jill R. Horwitz and Austin Nichols, “Hospital Ownership and Medical Services: Market Mix, Spillover Effects, and Nonprofit Objectives,” Journal of Health Economics 28 (5) (2009): 924–37, available at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0167629609000654.

43. American Hospital Association, “Partnerships, Mergers, and Acquisitions Can Provide Benefits to Certain Hospitals and Communities”; Claire E. O’Hanlon and others, “Access, Quality, and Financial Performance of Rural Hospitals Following Health System Affiliation,” Health Affairs 38 (12) (2019): 2095–2104, available at https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00918.

44. Jose Azar, Ioana Marinescu, and Marshall I. Steinbaum, “Labor Market Concentration.” Working Paper No. 24147 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2017, revised 2019), available at https://www.nber.org/papers/w24147; Efraim Benmelech, Nittai Bergman, and Hyunseob Kim, “Strong Employers and Weak Employees: How Does Employer Concentration Affect Wages?” Journal of Human Resources 57 (S) (2022): S200–S250, available at https://jhr.uwpress.org/content/wpjhr/57/S/S200.full.pdf; Kevin Rinz, “Labor Market Concentration, Earnings Inequality, and Earnings Mobility.” CARRA Working Paper Series 2018-10 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2018), available at https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/working-papers/2018/adrm/carra-wp-2018-10.pdf.

45. Prager and Schmitt, “Employer Consolidation and Wages: Evidence from Hospitals.”

46. Ibid.

47. Marissa Noles and others, “Rural Hospital Mergers and Acquisitions: Which Hospitals Are Being Acquired and How Are They Performing Afterward?” Journal of Healthcare Management 60 (6) (2015): 395–407, available at https://journals.lww.com/jhmonline/abstract/2015/11000/rural_hospital_mergers_and_acquisitions__which.5.aspx.

48. Sean Keehan and others, “National Health Expenditure Projects, 2022-31: Growth to Stabilize Once the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency Ends,” Health Affairs 42 (7) (2023): 886–898, available at https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2023.00403.

49. Kaiser Family Foundation, “Employer Health Benefits 2022 Annual Survey” (2022), available at https://www.kff.org/mental-health/report/2022-employer-health-benefits-survey/.

50. Daniel Arnold and Christopher Whaley, “Who Pays for Health Care Costs? The Effects of Health Care Prices on Wages.” Working Paper WR-A621-2 (RAND, 2020), available at https://www.rand.org/pubs/working_papers/WRA621-2.html.

51. Erin Trish and Bradley J. Herring, “How Do Health Insurer Market Concentration and Bargaining Power with Hospitals Affect Health Insurance Premiums?” Journal of Health Economics 42 (2015): 104–114, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2015.03.009.

52. American Hospital Association, “Fast Facts on U.S. Hospitals” (2023), available at https://www.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2023/05/Fast-Facts-on-US-Hospitals-2023.pdf; Government Accountability Office, “Health Care Capsule: Accessing Health Care in Rural America” (2023), available at https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-23-106651.pdf.

53. Dunc Williams and others, “Rural Hospital Mergers Increased Between 2005 and 2016 – What Did Those Hospitals Look Like?” INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing 57 (2020): 1–16, available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7370548/pdf/10.1177_0046958020935666.pdf.

54. American Hospital Association, “Rural Report: Challenges Facing Rural Communities and the Roadmap to Ensure Local Access to High-Quality, Affordable Care” (2019), available at https://www.aha.org/system/files/2019-02/rural-report-2019.pdf.

55. National Institute for Health Care Management, “Rural Health: Addressing Barriers to Care” (2023), available at https://infogram.com/2023-rural-health-infographic-1hdw2jpo1vn8p2l.

56. Williams and others, “Rural Hospital Mergers Increased Between 2005 and 2016 – What Did Those Hospitals Look Like?”; Cooper and others, “The Price Ain’t Right? Hospital Prices and Health Spending on the Privately Insured.”

57. Williams and others, “Rural Hospital Mergers Increased Between 2005 and 2016 – What Did Those Hospitals Look Like?”

58. Ibid.

59. Ibid; Teresa Harrison, “Hospital Mergers: Who Mergers with Whom?” Applied Economics, Taylor & Francis Journals 38 (6) (2006): 637–647, available at https://ideas.repec.org/a/taf/applec/v38y2006i6p637-647.html.

60. Sharita R. Thomas, G. Mark Holmes, and George H. Pink, “2012–14 Profitability of Urban and Rural Hospitals by Medicare Payment Classification” (Chapel Hill, NC: Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research at UNC, 2016), available at https://www.shepscenter.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/dlm_uploads/2016/03/Profitability-of-Rural-Hospitals.pdf.

61. Williams and others, “Rural Hospital Mergers Increased Between 2005 and 2016 – What Did Those Hospitals Look Like?”

62. Julia Foutz, Samantha Artiga, and Rachel Garfield, “The Role of Medicaid in Rural America” (Washington: Kaiser Family Foundation, 2017), available at https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-role-of-medicaid-in-rural-america/.

63. Caitlin Caroll and others, “Hospital Survival in Rural Markets: Closures, Mergers, And Profitability,” Health Affairs 42 (4) (2023), available at https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2022.01191.

64. American Hospital Association, “Partnerships, Mergers, and Acquisitions Can Provide Benefits to Certain Hospitals and Communities.”

65. American Hospital Association, “Hospital Mergers and Acquisitions Can Expand and Preserve Access to Care”; D.E. Burke and others, “Exploring Hospitals’ Adoption of Information Technology,” Journal of Medical Systems 26 (4) (2002): 349–355, available at https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/A:1015872805768; David M. Cutler and Fiona Scott Morton, “Hospitals, Market Share, and Consolidation,” Journal of the American Medical Association 310 (18) (2013): 1964–1970, available at https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/1769891.

66. Karen E. Joynt and others, “Quality of Care and Patient Outcomes in Critical Access Rural Hospitals,” Journal of the American Medical Association 306 (1) (2011): 45–52, available at https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/1104056; Karen E. Joynt, E. John Orav, and Ashish K. Jha, “Mortality Rates for Medicare Beneficiaries Admitted to Critical Access and Non–Critical Access Hospitals, 2002–2010,” Journal of the American Medical Association 309 (13) (2013): 1379–87, available at https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/1674237.

67. Marissa Noles and others, “Rural Hospital Mergers and Acquisitions: Which Hospitals Are Being Acquired and How Are They Performing Afterward?” Journal of Healthcare Management 60 (6) (2015): 395–407, available at https://journals.lww.com/jhmonline/abstract/2015/11000/rural_hospital_mergers_and_acquisitions__which.5.aspx; Rachel Mosher Henke and others, “Access to Obstetric, Behavioral Health, and Surgical Inpatient Services After Hospital Mergers in Rural Areas,” Health Affairs 40 (10) (2021): 1627–1636, available at https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00160; O’Hanlon and others, “Access, Quality, and Financial Performance of Rural Hospitals Following Health System Affiliation”; Jeffrey A. Alexander, Thomas A. D’Aunno, and Melissa J. Succi, “Determinants of Profound Organizational Change: Choice of Conversion or Closure Among Rural Hospitals,” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 37 (3) (1996): 238–51, available at https://doi.org/10.2307/2137294.

68. Bowen Garrett and Anuj Gangopadhyaya, “Who Gained Health Insurance Coverage Under the ACA, and Where Do They Live?” (Washington: Urban Institute, 2021), available at https://www.urban.org/research/publication/who-gained-health-insurance-coverage-under-aca-and-where-do-they-live.

69. Henke and others, “Access to Obstetric, Behavioral Health, and Surgical Inpatient Services After Hospital Mergers in Rural Areas.”

70. O’Hanlon and others, “Access, Quality, and Financial Performance of Rural Hospitals Following Health System Affiliation”; Hayley Drew Germack, Ryan Kandrack, and Grant R. Martsolf, “When Rural Hospitals Close, The Physician Workforce Goes,” Health Affairs 38 (12) (2019): 2086–2094, available at https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/pdf/10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00916.

71. Noles and others, “Rural Hospital Mergers and Acquisitions: Which Hospitals Are Being Acquired and How Are They Performing Afterward?”

72. Hannah Neprash, Michael E. Chernew, and J. Michaels McWilliams, “Little Evidence Exists to Support the Expectation That Providers Would Consolidate to Enter New Payment Models,” Health Affairs 36 (2) (2017), available at https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0840.

73. Gerald A. Doeksen, Cheryl F. St. Clair, and Fred C. Eilrich, “Economic Impact of a Critical Access Hospital on a Rural Community” (Virginia: National Center for Rural Health Works, 2016), available at https://ruralhealthworks.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/CAH-Study-FINAL-101116.pdf.

74. George M. Holmes and others, “The Effect of Rural Hospital Closures on Community Economic Health,” Health Services Research 41 (2) (2006): 467–85, available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00497.x.

75. Paula Chatterjee, Yuqing Lin, and Atheendar S. Venkataramani, “Changes in Economic Outcomes Before and After Rural Hospital Closures in the United Staes: A Difference-in-Differences Study,” Health Services Research 57 (5) (2022): 1020–1028, available at https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.13988; Diane Alexander and Michael R. Richards, “Economic Consequences of Hospital Closures,” Journal of Public Economics 221 (2023): 104821, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2023.104821

76. U.S. Census Bureau, “American Community Survey 2019” (U.S. Department of Commerce, 2019), available at https://www.census.gov/acs/www/data/data-tables-and-tools/data-profiles/2019/.

77. Carol K. Kane, “Updated Data on Physician Practice Arrangements: For the First Time Ever, Fewer Physicians are Owners Than Employees” (Washington: American Medical Association, 2019), available at https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2019-07/prp-fewer-owners-benchmark-survey-2018.pdf.

78. Matthew D. McHugh and others, “Nurses’ Widespread Job Dissatisfaction, Burnout, and Frustration with Health Benefits Signal Problems for Patient Care,” Health Affairs 30 (2) (2011): 202–10, available at https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0100.

79. Tait D. Shanafelt and others, “Changes in Burnout and Satisfaction With Work-Life Integration in Physicians During the First 2 Years of the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Mayo Clinic Proceedings 97 (12) (2022): 2248–2258, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2022.09.002; Joy Melnikow, Andrew Padovani, and Marykate Miller, “Frontline Physician Burnout During the COVID-19 Pandemic: National Survey Findings,” BMC Health Services Research 22 (365) (2022), available at https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s12913-022-07728-6; Meredith Bradley and Praveen Chahar, “COVID-19 Curbside Consults: Burnout of Healthcare Providers During COVID-19,” Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine (2020), available at https://www.ccjm.org/content/ccjom/early/2020/07/01/ccjm.87a.ccc051.full.pdf.

80. Leila Fadel and others, “As Hospitals Lose Revenue, More Than a Million Health Care Workers Lose Jobs,” NPR, May 8, 2020, available at https://www.npr.org/2020/05/08/852435761/as-hospitals-lose-revenue-thousands-of-health-care-workers-face-furloughs-layoff.

81. Martin Gaynor, “Diagnosing the Problem: Exploring the Effects of Consolidation and Anticompetitive Conduct in Health Care Markets,” Testimony before the House Committee on the Judiciary Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial, and Administrative Law, March 7, 2019, available at https://docs.house.gov/meetings/JU/JU05/20190307/109024/HHRG-116-JU05-Bio-GaynorM-20190307.pdf.

82. Prager and Schmitt, “Employer Consolidation and Wages: Evidence from Hospitals”; Azar, Marinescu, and Steinbaum, “Labor Market Concentration.”

83. American Hospital Association, “Partnerships, Mergers, and Acquisitions Can Provide Benefits to Certain Hospitals and Communities.”

84. Daniel Sullivan, “Monopsony Power in the Market for Nurses,” Journal of Law & Economics 32 (2) (1989): S135–S178, available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/725594.

85. Jeff Miles, “The Nursing Shortage, Wage-Information Sharing Among Competing Hospitals, and the Antitrust Laws: The Nurse Wages Antitrust Litigation,” Houston Journal of Health Law and Policy 7 (2007): 305–378, available at https://www.law.uh.edu/hjhlp/volumes/Vol_7_2/Miles.pdf.

86. Rob Wolff, “Nurse Wage-Fixing Cases – An Update” (San Francisco: Littler Mendelson, 2010), available at https://www.littler.com/publication-press/publication/nurse-wage-fixing-cases-update.

87. Laura Garcia, “3 San Antonio Hospital Systems Settle Nurses’ Wage Lawsuit,” San Antonio Express-News, January 29, 2020, available at https://www.expressnews.com/business/health-care/article/Three-San-Antonio-hospital-systems-settle-federal-15014976.php.

88. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Occupational Outlook Handbook: Registered Nurses” (U.S. Department of Labor, 2022), available at https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/registered-nurses.htm.

89. Prager and Schmitt, “Employer Consolidation and Wages: Evidence from Hospitals.”

90. Ibid.

91. Letter from Federal Trade Commission Bureau of Competition, Bureau of Economics, and Office of Policy and Planning to Texas Health and Human Services Commission, “Re: Certificate of Public Advantage Applications of Hendrick Health System and Shannon Health System,” September 11, 2020, available at https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/advocacy_documents/ftc-staff-comment-texas-health-human-services-commission-regarding-certificate-public-advantage/20100902010119texashhsccopacomment.pdf.

92. The Joint Commission, “Strategies for Addressing the Evolving Nursing Crisis,” The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety 29 (1) (2003): 41–50, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/S1549-3741(03)29006-7.

93. McHugh and Ma, “Wage, Work Environment, and Staffing: Effects on Nurse Outcomes.”

94. Janet Currie, Mehdi Farsi, and W. Bentley MacLeod, “Cut to the Bone? Hospital Takeovers and Nurse Employment Contracts,” ILR Review 58 (3) (2005): 471–493, available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/30038599.

95. McHugh and Ma, “Wage, Work Environment, and Staffing: Effects on Nurse Outcomes.”

96. Bonnie M. Jennings, “Chapter 24: Restructuring and Mergers.” In Hughes RG, ed., Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses (Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2008), available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2675/.

97. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Union Membership, Activity, and Compensation in 2022” (U.S. Department of Labor, 2023), available at https://www.bls.gov/spotlight/2023/union-membership-activity-and-compensation-in-2022/home.htm.

98. Prager and Schmitt, “Employer Consolidation and Wages: Evidence from Hospitals.”

99. National Nurses Union, “Nurses call on Federal Trade Commission and Department of Justice to strengthen guidelines to limit negative effects of mergers, acquisitions on patients and healthcare workers,” Press release, April 21, 2022, available at https://www.nationalnursesunited.org/press/nurses-call-on-ftc-and-doj-to-strengthen-merger-guidelines.

100. David I. Auerbach and Arthur L. Kellermann, “How Does Growth in Health Care Costs Affect the American Family?” (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2011), available at https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB9605.html; Cooper and others, “The Price Ain’t Right? Hospital Prices and Health Spending on the Privately Insured.”

101. Arnold and Whaley, “Who Pays for Health Care Costs? The Effects of Health Care Prices on Wages.”

102. Zack Cooper and others, “Do Higher-Priced Hospitals Deliver Higher-Quality Care?” Working Paper No. 29809 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2022, revised January 2023), available at https://www.nber.org/papers/w29809.

103. Schwartz and others, “What We Know About Provider Consolidation.”

104. Joanna H. Jiang and others, “Quality of Care Before and After Mergers and Acquisitions of Rural Hospitals,” Journal of the American Medical Association Network Open 4 (9) (2021), available at https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2784342; Erwin Wang and others, “Quality and Safety Outcomes of a Hospital Merger Following a Full Integration at a Safety Net Hospital,” Journal of the American Medical Association Network Open 5 (1) (2022), available at https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2787652; Beaulieu and others, “Changes in Quality of Care After Hospital Mergers and Acquisitions”; Cooper and others, “Do Higher-Priced Hospitals Deliver Higher-Quality Care?”; Ann S. O’Malley, Amelia M. Bond, Robert A. Berenson, “Rising Hospital Employment of Physicians: Better Quality, Higher Costs?” (Washington: Center for Studying Health System Change, 2011), available at http://www.hschange.org/CONTENT/1230/index.html.

105. Schwartz and others, “What We Know About Provider Consolidation.”

106. Ibid.

107. American Hospital Association, “Hospital Mergers and Acquisitions Can Expand and Preserve Access to Care.”

108. Ibid.

109. Jiang and others, “Quality of Care Before and After Mergers and Acquisitions of Rural Hospitals.”

110. Tamara B. Hayford, “The Impact of Hospital Mergers on Treatment Intensity and Health Outcomes,” Health Services Research 47 (3 Pt 1) (2012): 1008–1029, available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01351.x.

111. Daniel P. Kessler and Mark B. McClellan, “Is Hospital Competition Socially Wasteful?” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 115 (2) (2000): 577–615, available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/2587004.

112. Beaulieu and others, “Changes in Quality of Care After Hospital Mergers and Acquisitions.”

113. Government Accountability Office, “Maternal Health: Availability of Hospital-Based Obstetrics Care in Rural Areas” (2022), available at https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-23-105515.

114. Latoya Hill, Samantha Artiga, and Usha Ranji, “Racial Disparities in Maternal and Infant Health: Current Status and Efforts to Address Them” (Washington: Kaiser Family Foundation, 2022), available at https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/racial-disparities-in-maternal-and-infant-health-current-status-and-efforts-to-address-them/.

115. Katy B. Kozhimannil and others, “Association Between Loss of Hospital-Based Obstetric Services and Birth Outcomes in Rural Counties in the United States,” Journal of the American Medical Association 319 (12) (2018): 1239–1247, available at https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2674780.

116. Ibid.

117. Marco A. Villagrana, Elayne J. Heisler, and Paul D. Romero, “Closed, Converted, Merged, and New Hospitals with Medicare Rural Designations: January 2018 – November 2022” (Washington: Congressional Research Service, 2023), available at https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R47526.

118. Peiyin Hung and others, “Why Are Obstetric Units in Rural Hospitals Closing Their Doors?” Health Services Research 51 (4) (2016): 1546–1560, available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4946037/.

119. Henke and others, “Access to Obstetric, Behavioral Health, and Surgical Inpatient Services After Hospital Mergers in Rural Areas.”