Overview

Excessive market power plagues the U.S. economy.1 Market power increases the cost of goods and services for consumers, depresses prices and wages for those who supply dominant firms, and retards innovation, while creating profits that flow disproportionately to the wealthiest in society. Worse, the economically least-advantaged in society and those from historically disadvantaged groups are more likely to be the victims of market power and have the least ability to avoid its consequences. This dynamic exacerbates inequality and compounds the harms of structural racism.

Download FileRestoring competition in the United States: A vision for antitrust enforcement for the next administration and Congress

Antitrust enforcement has failed to prevent increased market power across the economy for a variety of reasons. Courts have made a series of policy judgments that favors nonintervention, leading to anticompetitive consolidation and conduct escaping condemnation. Congress has, over the past decade, failed to provide federal antitrust enforcers the resources to effectively enforce the laws. Too often, the agencies have been risk averse in case selection and failed to adopt an assertive enforcement agenda. Finally, agencies throughout the federal government have too frequently missed opportunities to protect or promote competition in their domains.

The incoming administration and the 117th Congress present an important opportunity to rethink fundamental questions surrounding U.S. antitrust laws and their enforcement. We need a new, bolder vision for competition policy. Antitrust enforcement must optimize deterrence, and promoting competition must be a priority across the government, not just for antitrust enforcers.

In this report, we call for the next administration to undertake three fundamental changes to competition policy, the antitrust laws, and their enforcement:

- Devote resources to the passage of new antitrust legislation and increase resources for antitrust enforcement. Congress needs to step in, as it has before, to clarify or overrule judicial rules that reflect unsound economic theories or unsupported empirical claims, and enact new laws to deal with new problems. To support this enforcement agenda, Congress should appropriate $600 million in increased annual funding for the Federal Trade Commission and the Antitrust Division of the U.S. Department of Justice for antitrust enforcement.

- Revitalize antitrust enforcement with a focus on strengthening deterrence. The next administration must appoint agency leaders who recognize that market power is a serious and growing problem, who understand that economic research supports more aggressive enforcement, and above all, who believe that business as usual will not suffice. The Antitrust Division and the Federal Trade Commission should commit to an active strategic enforcement agenda that targets priority areas for enforcement.

- Commit to a “whole government” approach to competition policy. Numerous federal agencies’ decisions affect competition in the United States, sometimes implicitly, sometimes explicitly. The new administration should establish a White House Office of Competition Policy within the White House National Economic Council to promote rulemakings that catalyze competition and reverse those that entrench incumbents or suppress competition.

A vision to revitalize antitrust enforcement in the United States

The evidence for the growing market power problem in the United States is varied and rich. Studies show substantial and growing market power across a number of industries.2 Monopolies increase the prices of critical goods, such as pharmaceutical products, and reduce the quality of services, such as dialysis. Monopoly power also tends to retard innovation and dampen economic growth. And monopsony power reduces competition among employers, leading to lower wages or benefits, or worse working conditions. More subtly, market power can exacerbate other social problems.

Although market power harms many people, the less advantaged members of society are the least able to avoid the consequences of higher prices or lower quality, the least able to access higher wages offered by more competitive labor markets, and the least likely to share in the wealth created by the higher share prices associated with increased corporate profits. Because of this, the rise in market power tends to exacerbate income inequality and compound the harms of racial inequality. Strong antitrust enforcement directed at business conduct that harms competition can deliver many beneficial byproducts, among them reducing inequality, advancing the diversity of voices (a First Amendment goal), discouraging threats to democracy from concentrated political power, and expanding opportunities for small businesses to compete.3

The federal government is responsible for fostering competition and preventing the abuse of market power. Unfortunately, antitrust enforcement has been stagnant or declining for many years, contributing to today’s market power problems.4 By antitrust enforcement, we mean the collection of institutions tasked with protecting competition and tackling the abuse of market power in the United States. They include the Antitrust Division at the U.S. Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission (hereafter, Antitrust Division and FTC, or the antitrust enforcement agencies), the U.S. Congress, and the federal courts. While antitrust enforcement prevents the accumulation and abuse of market power, other federal agencies make decisions that affect competition.

Antitrust enforcement cannot solve all of the social and economic problems in the United States or even address all the competition issues that plague the U.S. economy today. For example, shifts in consumer buying patterns and failure of small, especially local, businesses in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic and COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus, may expand the dominance of large digital platforms. And the current public health and economic crises may lead to fewer firms with more market power across a number of industries. Antitrust enforcement has limited tools to overcome that dynamic, although it can prevent anticompetitive acquisitions of competitors, challenge conduct that raises rivals’ costs, and prosecute cartels that attempt to exploit the crisis.

A clear, high-level commitment to promoting competition is critical to overcome the challenges facing antitrust enforcement, which, as antitrust scholars and practitioners, we have seen firsthand. Congress, the two antitrust enforcement agencies, and the executive branch all have a role to play in turning this vision into a reality. No single part of government can fully revitalize competition on its own.

The role of Congress

The meaning of the antitrust laws rests first with Congress, as does their importance, which is reflected in yearly appropriations. Judicial interpretations have eviscerated competition enforcement. Courts have failed to appreciate the benefits of competition and have underestimated the harm of anticompetitive conduct. They have overestimated the ability of markets to correct themselves without proper antitrust enforcement. And they have even praised the benefits of monopoly.5 Too often, the resulting legal standards allow anticompetitive conduct to escape condemnation. At the same time that the courts have made it harder for antitrust enforcers to win meritorious antitrust cases, Congress has provided the enforcers fewer resources to do their jobs.

The next administration should seize this moment of both bipartisan and solid public support for stronger antitrust enforcement to seek legislative action that would restore the core functions of the antitrust laws. Legislation is difficult and risky, but the potential benefits of substantial change in antitrust enforcement are enormous. We recommend three types of legislative proposals: substantive changes to the antitrust laws, increased funding, and a series of procedural changes that would make government enforcement more efficient and effective.

The role of the two antitrust enforcement agencies

Market power in the United States is a target-rich environment for antitrust enforcement. The struggle will not be finding those targets, but prioritizing them, which is why we recommend the legislation detailed briefly above. Without new legislation, the agencies can still address these issues, but the task will be more challenging and take far longer. The antitrust enforcement agencies nonetheless have a duty to attack anticompetitive conduct in the face of those obstacles. They also have a responsibility to advocate for the development of legal doctrine that reflects sound economic principles even when facing bad precedent.

Many have criticized the antitrust enforcement agencies during the Obama and Trump administrations for failing to challenge the monopoly conduct of dominant firms in the U.S. economy, for allowing mergers to proceed that led to highly concentrated markets, and for overlooking anticompetitive conduct that harms small businesses and workers.6 Others have defended the two agencies’ records.7 They point to successes in big merger cases, in hospital mergers, and in stopping pay-for-delay patent settlements.

While we believe antitrust enforcement has been too timid over the past 20 years, that debate is about the wrong issue. The real question, given the current state of market power in the United States, is how the antitrust enforcers can best protect competition, which requires a focus on general deterrence. This requires a strategic enforcement agenda, vigorously executed to address one or more of the most critical unchecked challenges to competition confronting our economy, such as:

- Exclusionary conduct by dominant firms, and their acquisitions of nascent competitors

- Vertical mergers that raise rivals’ costs

- Horizontal mergers in moderately or highly concentrated markets

- Specific sectors of the economy, such as digital platforms, agriculture, or healthcare, where anticompetitive outcomes have enormous consequences

- Anticompetitive acquisitions and labor market practices that reduce employer competition and harm workers

Today, progress requires a strategic enforcement agenda and leaders at the Antitrust Division and the Federal Trade Commission who have the vision and experience to implement that agenda.

Prioritizing competition as a federal government goal

Antitrust enforcement is not the only weapon in the federal government’s arsenal to attack market power. Regulatory agencies, from the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to the U.S. Department of Transportation and the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, issue rules that implicitly or explicitly define or modify the rules of market engagement. These agencies and many others can open up competition through well-designed regulations. The Federal Trade Commission also has authority to issue rules to promote competition.

Too often, these tools lie dormant, or worse, regulations unnecessarily or even intentionally limit competition. We urge the next administration to create a White House Office of Competition Policy to raise the prominence of procompetition policies across the federal government. We also recommend that the Federal Trade Commission use its existing but dormant rulemaking authority to promote competition.

In the pages that follow, this report addresses these three broad areas to revitalize competition in in the United States. The next section focuses on the role of Congress and the types of reforms the new administration should work with the next Congress to enact. The report then turns to how the two federal antitrust enforcement agencies can optimize deterrence. We then close the report with a presentation of additional tools to improve competition: creating a White House Office of Competition Policy and utilizing the Federal Trade Commission’s dormant rulemaking authority on competition matters.

Congressional action to strengthen antitrust enforcement

The U.S. Congress plays a critical role in competition policy. Since the passage of the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, it has generally allowed the courts to define the meaning of the antitrust laws. But Congress periodically asserts its prerogative to define what is legal and what is not. Examples of this include:

- The 1914 Clayton Antitrust Act, which defined certain anticompetitive acts more specifically, and the 1914 Federal Trade Commission Act, which created and empowered the independent FTC. Both were enacted in response to what Congress viewed as an overly narrow interpretation of the Sherman Act by the courts8

- The Celler-Kefauver Antimerger Act of 1950, which strengthened merger enforcement generally, closed loopholes, and expanded the reach of the law to apply to vertical and conglomerate mergers

- The Hart-Scott-Rodino Act of 1976, which required prior notification of mergers, enabling the Antitrust Division and Federal Trade Commission to investigate and challenge anticompetitive mergers before they are consummated

An emerging bipartisan consensus in Congress recognizes that the time has come for Congress to act once again. This reflects the widespread concern that the antitrust laws, as interpreted today, no longer prevent the growth and abuse of market power. The majority report of the House of Representatives’ Antitrust Subcommittee on Competition in Digital Markets calls for significant legislative reforms to the antitrust laws to address these concerns. And the Third Way report by Rep. Ken Buck (R-CO), though more modest in scope, expressed support for legislation that would create new presumptions of illegality for certain types of mergers and would remind “the agencies and the courts of the original congressional intent behind the antitrust laws.”9

Congress also can also improve antitrust enforcement through the power of the purse and technical changes that make enforcement more efficient. In this section of our report, we will examine how Congress can specifically improve antitrust enforcement by:

- Enacting substantive antitrust reforms

- Addressing procedural antitrust reforms

- Providing more financial resources to the two federal antitrust agencies

In these three ways, Congress can begin to change the way the federal government strengthens antitrust enforcement in the United States.

Substantive antitrust reforms

Over the past 40 years, the federal courts have increasingly advanced a skeptical and cramped view of the antitrust laws. They often rely on economic assumptions that, at best, are no longer valid and, at worst, never were.10 As a result, the courts increasingly saddle plaintiffs with inappropriate burdens, making it unnecessarily difficult to prove meritorious cases and allowing anticompetitive conduct to escape condemnation.11

In two recent merger cases, for example, courts expressed doubt that a company would use its enhanced market power to increase its profits.12 Courts too often reject the best, direct evidence of anticompetitive harm, and instead require an elaborate analysis of indirect evidence of market definition, market share, and market power.13 In the recent Federal Trade Commission v. Qualcomm Inc. case, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit even concluded, bizarrely, that harm to customers is not a relevant anticompetitive harm.14

Together, flawed legal precedent and erroneous economic reasoning create a daunting hurdle to effective antitrust enforcement. The resulting harm goes far beyond the effects in individual cases. None of this is what Congress intended when it passed the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 and subsequent antitrust laws over the course of the 20th century. Without further legislative direction, the courts are almost certain to continue to narrow antitrust protections. Market power will increase. More consumers and companies will buy goods and services from dominant firms. More small business and workers will sell to, or work for, firms with monopsony power. Less innovation will occur. And the negative byproducts of market power—increased inequality, less diversity of voices, and increased concentration of political power—will worsen.

Without significant legislative reform, more vigorous antitrust enforcement likely will have only a modest impact on market power. Although effective litigation strategies can limit or overturn bad legal precedents or develop new ones, that process is painfully slow. It can take years to achieve even a single success. And given the current perspective of the federal courts, there is no guarantee that aggressive litigation strategies will be successful.

Congress need not passively accept today’s cramped interpretation of the antitrust laws. It should once again reassert its commitment to competition by updating our antitrust laws and directing the courts to better protect competition, consumers, and workers. Legislation allows Congress to make broad policy judgments about what the antitrust laws should prohibit and the best legal rules for achieving those results.

Meaningful antitrust reform should be a priority of the next administration and the 117th U.S. Congress. The challenge of drafting legislation is substantial. On the one hand, the legislation must be written for a judiciary that is both increasingly hostile to antitrust claims in general and increasingly textualist in its statutory interpretation. On the other hand, in the context of the antitrust laws, courts have often “abandoned statutory textualism” to interpret the laws “in favor of big business,”15 explains Daniel Crane, the Fredrick Paul Furth Sr. professor of law at the University of Michigan Law School. If given discretion to interpret new legislation, the current judiciary is likely to fall back on the same skepticism of antitrust enforcement that it has advanced over the past 40 years.

Despite those concerns, legislation remains the best option to revitalizing antitrust enforcement. In drafting legislation, Congress can learn from the past. One case in point: The legislative history of the Celler-Kefauver bill, not its text, reveals the bill’s intent, which courts increasingly ignore.16 Congress can reduce that risk by being explicit in the text when vacating or rejecting existing precedent and when identifying relevant factors, such as the importance of protecting both actual and potential competition. Congress should identify in statute the elements sufficient to establish an antitrust violation as precisely as possible.

In particular, Congress should specify the circumstances under which the burden of proof switches from the plaintiff to the defendant and the evidence necessary to rebut presumptions of illegality once they are established, based on the underlying economics, the type of evidence available to the parties, and the respective risks of underenforcement and overenforcement. Because courts regularly apply burden shifting across many areas of the law, they will understand and respect its implications.17 Successful legislative reform would accomplish the following goals:

- Correct flawed judicial rules that reflect unsound economic theories or unsupported empirical claims18

- Clarify that the antitrust laws protect against competitive harms from the loss of potential and nascent competition, especially harms to innovation

- Incorporate presumptions of illegality that better reflect the likelihood that certain practices harm competition

- Recognize that under some circumstances conduct that creates a risk of substantial harm should be unlawful even if the harm cannot be shown to be more likely than not

- Alter substantive legal standards and the allocation of pleading, production, and proof burdens to reduce barriers to demonstrating meritorious cases19

We are under no illusion about the difficulty in passing legislation, but it remains the best way to address deficiencies in the current application of our antitrust laws. And the time seems ripe for bipartisan support of this effort.

Procedural antitrust reforms20

In addition to these substantive changes, Congress should enact procedural reforms to improve antitrust enforcement by the two antitrust enforcement agencies. Appendix A describes the needed legislative changes and explains why they are needed. Specifically, these changes would:

- Affirm the right of the two federal antitrust enforcement agencies to obtain equitable monetary remedies

- Update merger filing procedures under the Hart-Scott-Rodino Act

- Adjust merger filing fees under the Hart-Scott-Rodino Act

- Streamline small-deal review through a Quick File system

- Modernize the Federal Trade Commission’s jurisdiction and process

- Confirm the Federal Trade Commission’s authority to engage in competition rulemaking

- Provide the Justice Department’s Antitrust Division with industry-study authority comparable to Section 6(b) of the FTC Act

These procedural changes should be uncontroversial. Except for confirming the FTC’s authority to engage in competition rulemaking, they address primarily unintended consequences arising from the circumvention of antitrust enforcement processes. Although competition rulemaking is more controversial, this proposal would codify existing caselaw.21

The need for more resources

The agencies lack the resources to fulfill their mission after a decade in which they have seen their budgets largely frozen. Increasing resources alone will not solve today’s manifest market power problems, but substantially increasing resources is an important part of the solution.

The agencies require a significant increase in appropriations to begin the process of more effectively deterring anticompetitive conduct and mergers. Agencies strapped for resources are less likely to investigate complex cases and more willing to accept flawed settlements. Corporations are more likely to pursue questionable mergers or undertake potentially anticompetitive conduct if they think the agencies have little or no capacity to bring additional enforcement actions.

Limited resources constrain enforcement activity

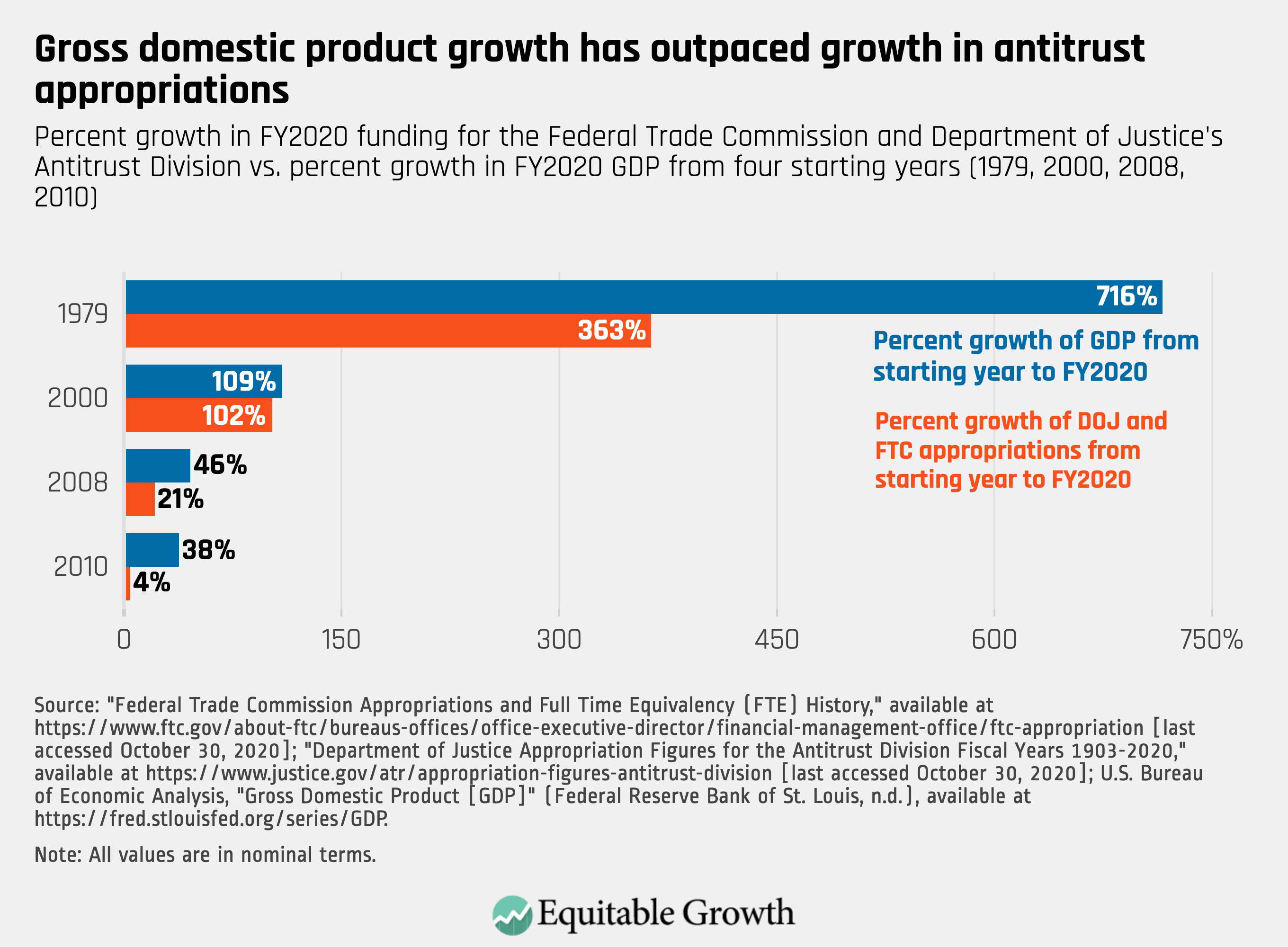

Over the course of the previous decade, total appropriations to the Federal Trade Commission and the Antitrust Division barely grew in nominal terms. Antitrust appropriations have been nearly flat in the past decade, despite nearly 40 percent growth in U.S. Gross Domestic Product. (See Figure 1.) The Antitrust Division had 25 percent fewer full-time employees in 2019 than it did 10 years earlier.22 And the Federal Trade Commission has roughly the same number of full-time employees as it did in 2009.23

Figure 1

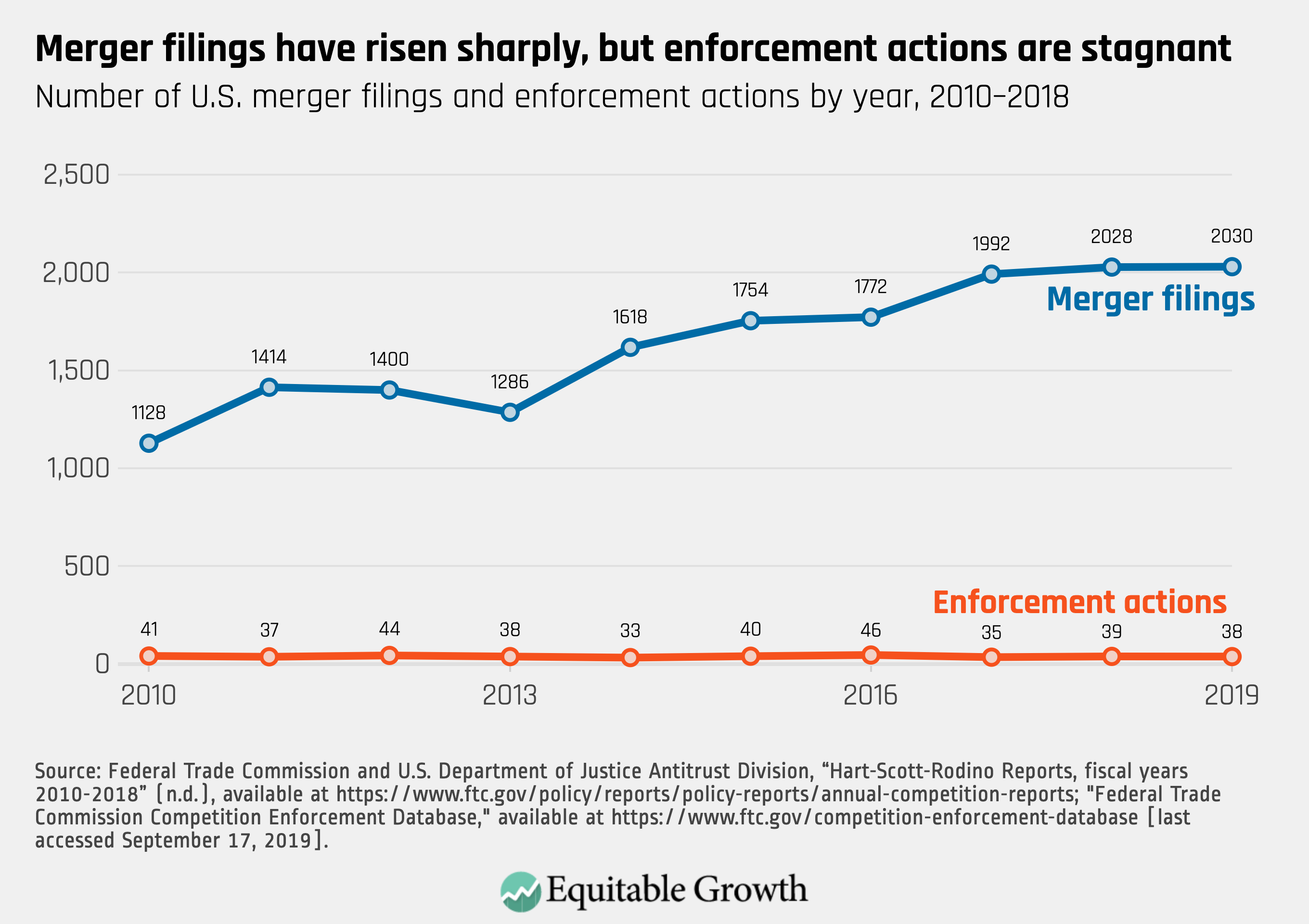

This austerity occurred even while the need for antitrust enforcement grew as market power in the U.S. economy grew. Merger filings increased dramatically; civil antitrust enforcement was flat.24 (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

The two antitrust agencies were no more aggressive, and probably less aggressive, in bringing cases, with the exception of hospital mergers and challenging pharmaceutical patent settlements.25 At the same to time, the enforcement actions that did happen required the government to try more cases to judgment, despite being no more aggressive in case selection.26 That combination of flat appropriations, more trials, but no more aggressive enforcement agenda indicates that the agencies’ budgets have sharply limited their capacity to bring antitrust cases.

Resource limitations also undermine the agencies’ mission in other ways. One way to improve enforcement, for example, is through merger retrospectives, which study the impact of mergers, enforcement actions, and settlements. In the past, such studies helped the Federal Trade Commission reinvigorate its enforcement effort against hospital mergers.27 Regularly, there are calls for more retrospectives, but those studies are time-consuming and data-intensive, and thus expensive. Current budgets limit the agencies’ ability to fulfill these responsibilities as well.

Increase enforcement agency resources by $600 million

How much should Congress appropriate annually? There is bipartisan recognition of inadequate funding for antitrust enforcement and bipartisan support for increasing resources.28 We estimate the total resources for the FTC’s competition mission and the Antitrust Division were $312 million during FY2020.29 We propose increasing the annual appropriations to the Federal Trade Commission and the Antitrust Division by $600 million.

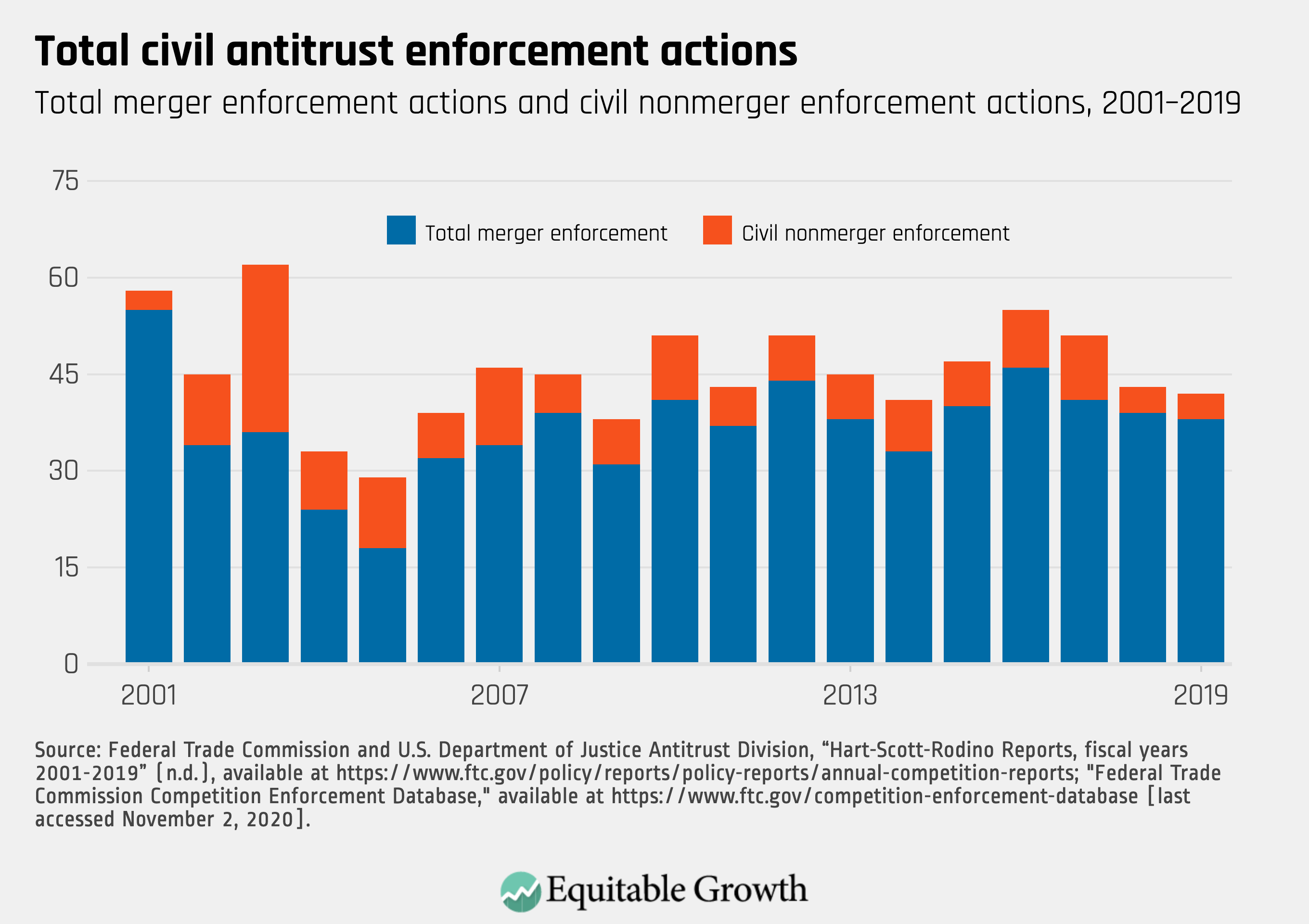

This amount reflects roughly a 200 percent increase and reflects both the need for greater antitrust enforcement and the increased challenges the agencies face. Increasing the budget would allow for significant expansion in all three areas of antitrust enforcement—criminal, merger, and civil nonmerger. The two agencies have brought between 30 and 60 civil actions per year since 2001. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

Our proposal would give the agencies the capacity to investigate more problematic behavior and then take 60–100 enforcement actions a year.

This increase would expand the agencies’ capacity and allow them to implement a strategic agenda to optimize deterrence. They need to strengthen existing legal rules and develop new doctrines related to mergers, potential competition, buyer power, labor market harms, vertical restraints, and predation. Compared to 2008, there is more evidence that the consolidation and abuse of market power is a systemic issue in a number of areas, including digital marketplaces, agriculture, and labor markets. A successful strategic agenda will require, at least initially, fewer settlements and more litigation. The agencies will be less likely to settle cases as they place a greater priority on establishing strong precedent. Defendants, however, are more likely to litigate until the case law shifts in favor of stronger antitrust enforcement by limiting existing precedents or by adopting new ones.

The two agencies also will need additional funding to conduct policy studies, perform merger retrospectives, promulgate rules at the Federal Trade Commission, and take a more active role in advocating for competitive policies in other regulatory agencies, whether under the current system or as part of a new White House task force, which we discuss in the last section of this report.

How the antitrust enforcement agencies can optimize deterrence

Antitrust enforcement faces a serious deterrence problem, if not a crisis. Deterrence is central to most civil and criminal law enforcement programs because catching every lawbreaker is either implausible or would require an immense enforcement apparatus. The antitrust laws, by their very nature, will always lack some of the deterrent clarity characteristics of other legal regimes.30 Yet there is reason to fear we have reached an extreme. Rather than deter anticompetitive behavior, current legal standards do the opposite: They encourage it because such conduct is likely to escape condemnation, and the benefits of violating the law far exceed the potential penalties.31

Antitrust enforcement’s current reactive posture has contributed to this problem. Enforcers typically respond to cases and complaints that come before them. 32 Reactive enforcement works well when anticompetitive conduct is rare and is the exception across the U.S. economy.33 But reactive enforcement is unlikely to address wide-ranging competition problems, and may even exacerbate them, when it spreads limited resources broadly, making it difficult to tackle major competitive problems when powerful interests will expend substantial resources to defend their actions.

A reactive approach also may largely accept existing legal precedents and try to operate within that reality. The combination can create a ratchet: Court decisions that limit enforcement tend to circumscribe later enforcement. There are no countervailing forces to convince courts to develop rules based on sound economics that will strengthen enforcement.

When market power is prevalent and growing across multiple industries, optimizing deterrence requires a strategic antitrust enforcement agenda. Such an agenda recognizes that the antitrust enforcement agencies must devote substantial resources to affirmatively attack problematic practices and focus on industries in which market power is pervasive. Prior enforcers employed this approach in the past. Both the Antitrust Division and the FTC made a concerted effort during the Clinton administration to convince courts to block mergers based on unilateral effects, which has allowed the government to block anticompetitive transactions that would have been far more difficult to block under preexisting theories. Major monopolization cases, such as the Antitrust Division’s United States v. Microsoft Corp. case, also required a direct and focused attack.34

At the Federal Trade Commission, Chairman Timothy Muris implemented a strategic enforcement agenda during his tenure, leveraging the full scope of the FTC’s resources of litigation, hearings, policy studies, and empirical research.35 His tenure led to the agency overcoming a series of court decisions that left hospital mergers seemingly beyond the reach of the antitrust laws, established a structured approach to the rule of reason test for horizontal agreements, and limited judicially created exemptions to the antitrust laws.36 The next chair of the FTC, Jon Leibowitz, also leveraged the full scope of agency resources during his tenure from 2009–2013. During that time, the agency was able, after a decade of setbacks, to successfully vacate judicial precedent that treated pay-for-delay patent settlements as effectively per se legal and largely stop a practice that increased prescription drug prices by tens of billions of dollars.37

Although these examples provide both a model for strategic enforcement and proof of concept, we envision a strategic enforcement agenda that is broader, more deliberate, and bolder than prior efforts. In the current legal environment, the agencies face difficult challenges. And no one should overestimate how much they alone can change competition policy. The next administration can maximize the impact of antitrust enforcement by appointing leaders who understand the challenges and commit to design and implement a strategic enforcement agenda.

Appoint leaders who understand the challenges

Regardless of the need for new legislation, the antitrust agencies have a duty to attack monopoly power where they find it and to advocate for courts to update and modify their doctrines to conform to modern economic learning.

Competent, talented, and dedicated staff fill both agencies. They continue to pursue the agencies’ mission in a hostile legal environment and typically against corporate interests, whose financial resources dwarf those wielded by the federal government. Career staff look to the leadership to set the priorities and identify areas where they should be strategic and, as needed, take risks. When the agencies have been overly cautious, the fault generally lies with leadership failing to provide a vision of enforcement. Successful leadership at the agencies involves motivating and inspiring staff while setting strategic direction, and requires the following qualities:

- Integrity in decision-making

- A vision for competition policy and enforcement

- Leadership experience and communications skills

- Management skills

- Commitment to diversity and staff renewal

- Understanding the role between competition and larger issues

Integrity in decision-making

Successfully addressing anticompetitive conduct relies heavily on deterrence. That can occur only if agencies enforce the antitrust laws without fear or favor and on a principled basis. Even the appearance of favoritism or inappropriate decision-making can undermine deterrence.

Unfortunately, the current political leadership of the Department of Justice and the Antitrust Division have damaged the integrity of the Antitrust Division. The Justice Department has spent substantial antitrust resources investigating cannabis markets that raised no possibility of competitive harm. It has publicly pursued baseless antitrust charges against auto manufacturers that disagreed with the Trump administration’s views on environmental policy.38 And its inconsistency in merger enforcement has raised further alarm over political interference, while also harming deterrence in its own right. For example, it adamantly refused to accept a behavioral remedy and unsuccessfully challenged AT&T Inc.’s acquisition of Time Warner Inc., which involved a defendant that owned a cable network, CNN, that President Donald Trump often criticized.39

Yet the same leadership negotiated a behavioral remedy to address T-Mobile USA’s acquisition of Sprint Corp., a case that raised more traditional antitrust concerns. The two companies engaged in an open lobbying campaign largely unrelated to the competitive impact of their proposed merger.40 The appearance that companies receive more favorable treatment when they provide political support to an administration destroys effective deterrence and agency credibility.

A vision for competition policy and enforcement

The choice of leadership for the antitrust agencies—most especially the assistant attorney general of the Antitrust Division and the chair of the Federal Trade Commission—will have enormous impact on whether the next administration can succeed in turning the U.S. economy toward competition. These leaders must recognize that market power is a growing problem and that economic research supports more aggressive enforcement.41 They must develop and communicate a strategic enforcement agenda to invigorate enforcement. They must have the credibility and ability to implement that agenda. And they must both make a commitment to serve long enough to execute on its promise.

The assistant attorney general and the FTC chair must implement a strategy for effectively increasing the impact of antitrust enforcement. A complacent or largely reactive posture is an inadequate response to the competition problems facing the U.S. economy at this critical moment. Their experience, research, and public positions should evidence a bold vision for reasserting vigorous enforcement. They should not believe that antitrust reforms require only a minor course correction. The ideal candidates would have a history of taking on corporate power during periods of their career, a demonstrated willingness to challenge existing assumptions, and a commitment to work to develop the law to make antitrust enforcement more effective.

Executing on this strategy will require that these leaders have few potential conflicts that would necessitate recusals in any priority enforcement area. They must also exhibit a willingness to challenge anticompetitive actions without regard to positions they have taken in the past or potential future professional relationships. Each leader should be focused on the position as an end in itself and not as a stepping stone to their next position. Successfully implementing a renewed antitrust agenda requires a commitment. We recommend that anyone accepting the job of chair of the Federal Trade Commission or assistant attorney general for the Antitrust Division commit to serve for a minimum of 3 years from confirmation.

Leadership experience and communications skills

The two new leaders of the antitrust agencies should have the experience and skills necessary both to implement their enforcement vision and to educate the public about the importance of competition to economic growth and economic opportunity. The problems of growing market power and anticompetitive conduct create enforcement and communications challenges that antitrust agency leaders have not systematically confronted for decades.

Enforcers today need to go beyond fine-tuning the lines between legal and illegal conduct as found in the case law. They need to communicate their evidence-based enforcement standards to policymakers throughout the federal government and to the public at large. To strengthen deterrence of anticompetitive conduct and mergers in the absence of new antitrust legislation, agency leaders must direct strategies that will convince the courts to move the lines across many areas of legal doctrine.

Enforcers operate within existing precedent, which requires a different approach and strategy than what might work in a free-wheeling public policy debate. They can seek to expand, modify, limit, or overturn precedent, but they cannot ignore it. Oftentimes, improving judicial rules will require a long-term strategy that relies on a series of incremental successes. Making progress calls for both an enforcement strategy and a communications strategy. This, in turn, requires agency leaders who are experienced in litigation, knowledgeable about antitrust economics and legal doctrine, able to think strategically, and capable of making legal and economic concepts understandable to the public, as well as to the antitrust community.

The new agency leadership must communicate the harm of a systematic market power problem across multiple industries or sectors of the economy, both when speaking in general terms and when bringing individual enforcement actions. Doing so will increase public recognition of the current underdeterrence problem and help shape the general attitudes that judges and legislators bring to their work.

For too long, the priority at the antitrust agencies has been communicating with the lawyers, economists, and academicians who work in the field of antitrust. Today, however, the problems of market power and insufficient competition are also of general interest to the wider U.S. public. Even more important, those concerns intersect with a wide variety of other major current problems, such as rising economic inequality, in ways that have policy consequences and generate natural allies for antitrust enforcers.42

The agencies must change their historical habits and become more externally focused. Leaders of the agencies should educate the public about competition enforcement across a wide variety of settings and media. They must prioritize industries, harms, and legal doctrines based on the extent of the market power problems and the likelihood of enforcement success. They must communicate those priorities, both to inform the public about why antitrust helps them and to enlist the public in helping them identify specific targets for investigation. They must follow through with cases to back up their rhetoric with action.

The two new leaders must also display patience, confidence, and judgment to maximize the prospects for success and minimize the risk that a hostile judiciary will make things worse. The agency leaders must not overpromise in their communication. The Antitrust Division, at the beginning of the Obama administration, withdrew the prior guidelines of enforcing Section 2 of the Sherman Act and held field hearings on competition in agricultural markets. Neither resulted in a substantial change in enforcement, which likely undermined deterrence. It will be necessary, at times, to accept settlements or postpone enforcement while waiting for stronger facts before pushing the courts to change the law. All of these tasks will require leadership teams with deep experience and strategic vision, as well as an ability to communicate externally.

Management skills

The incoming leaders of the antitrust agencies must be able to leverage limited resources to maximize enforcement effectiveness. Success requires the willingness to take risks and focus on important issues that have a big impact on the U.S. economy. They must ensure that their agencies are strategic and disciplined.

The challenge for the antitrust agencies in 2021 and beyond will not be identifying competition problems in the economy, but rather establishing priorities to maximize their impact and generate deterrence. If the agencies take on too many cases or pick cases that have no chance of success, they will fail in this goal. Successfully identifying the right targets requires an understanding of investigation, economics, and litigation.

The new leaders of the two agencies must be able to manage resources and inspire staff. Our belief is that staff today are eager to do more under strong leadership.

Commitment to diversity and staff renewal

As the agencies rebuild their staffing levels, there must be a plan to restore capabilities lost during the attrition of the past 4 years, particularly at the Antitrust Division, and a long-term public commitment to improve the capabilities and diversity of their respective staff—even more if increased appropriations facilitate additional hiring. Strategic hiring presents an opportunity to address the lack of diversity in the antitrust profession. Although government enforcers have been better at improving diversity than the profession as whole, the agencies can improve diversity further. Agency outreach has the potential to improve diversity in the pipeline, to the benefit of the agencies, the antitrust profession, and society.

This effort can build connections to expand the pool from which agencies recruit paralegals, attorneys, economists, and other professionals. The agencies can reap further benefits of a multifaceted pool of talent and voices by expanding professional development efforts and aiming to increase the diversity of candidates for management and senior management positions. Recruitment, the injection of new perspectives, and staff renewal all may be further enhanced by more robust internship or visiting programs for junior faculty, Ph.D. candidates or postdoctoral students, and public interest lawyers.

Understanding the role between competition and larger issues

Individual antitrust cases are not about challenging political power or weighing broad social policy goals in individual cases. But it would be foolish to not to recognize that growing market power has broad social impacts beyond specific enforcement actions. The leaders of the enforcement agencies must understand that relationship. This is not to say that antitrust should be used as a tool for broad social change. Rather, enforcers should recognize that tackling rising market power will have benefits that the reach across society.

The harms from increased market power do not fall equally on all consumers. If airlines raise prices by hiding certain fees, for example, then business travelers buying through a corporate program or high-income consumers using a service provided by their credit cards may be aware of the fee, able to avoid it, or bargain to remove it. Ordinary consumers are not as insulated. They are more likely to suffer from the exercise of market power because, in general, they can access fewer choices in the marketplace.

Moreover, the harms associated with having to pay elevated prices due to monopoly power or accept lower wages in noncompetitive labor markets likely are greater for lower-income consumers and those from marginalized communities. In exercising prosecutorial discretion, the agencies should consider whether a merger tends to harm vulnerable groups. It would be a poor trade-off if a merger threatens to increase prices at the low end of the market while the merging parties claim an efficiency such as future innovation that will be rolled out in the most expensive products long before being introduced in the products or services sold to most buyers.

The two agencies, therefore, should be more willing to bring cases challenging practices that disproportionately affect members of historically disadvantaged groups because, for these reasons, it is likely that the harm they bear will be larger than that of other consumers. Agency leaders can increase their effectiveness by communicating the benefits they hope to achieve using antitrust enforcement on behalf of vulnerable consumers by explicitly recognizing how competition benefits historically disadvantaged groups and creating common cause with other agencies and organizations that are also working for more equity for low-income consumers in society.

Implement strategic antitrust enforcement

Inadequate deterrence under the current antitrust enforcement regime manifests itself in many ways. Some companies openly discuss neutralizing competitors by acquisition,43 and others propose mergers in industries that reduce the number of competitors from four to three, or even three to two—mergers that, in the past, were likely to have been challenged.44 Large and powerful firms often act as though the antitrust laws are particularly toothless when it comes to exclusionary conduct or acquisitions of nascent competitors.45

Today, companies that can afford good lawyers too often ignore the antitrust laws, reasoning that any resulting penalties can be avoided or dealt with later at modest cost. Given the inconsistency of enforcement and the potential for cheap settlements, why not? The antitrust laws are now failing in their central goal of protecting and promoting competition across the entire U.S. economy—even if the antitrust agencies win an occasional victory in court. Nor does the ability of state attorneys general and private plaintiffs to bring antitrust cases create adequate deterrence because of the state of the case law, particularly for private plaintiffs.

Building a successful enforcement program that restores deterrence should be the central antitrust objective of the next administration. The agencies must announce that previously tolerated conduct will face legal challenges, and enough cases must be brought and won to cause a widespread shift in corporate behavior. Put simply: One needs clear communication, and directed and persistent enforcement should be the watchwords of the next administration. The successes and failures of the past 20 years offer the best guide for success. Without discounting the challenges posed by a sometimes-hostile federal judiciary, the story of successes and failures illustrates a strategy for progress and, in particular, patiently laying the groundwork for an enforcement campaign.

Restoring deterrence also will require the agencies to rethink certain aspects of their role. To exaggerate just a little, outsiders often see the agencies as a mysterious branch of the federal government, almost judicial in their posture. Implementing a strategic and effective antitrust enforcement regime will require that the agencies become more transparent about what they are doing and why. Agency communication should be aimed not only at antitrust lawyers but also at business executives, policymakers, and the general public.

The remainder of this section reviews the past 20 years of enforcement to:

- Describe lessons learned over the past 20 years

- Map out a new strategic enforcement agenda

- Present the use of remedies to strengthen deterrence

- Address a new criminal enforcement agenda

Lessons learned over the past 20 years

With some exceptions, antitrust agencies over the past 20 years have not provided a clear and consistent picture of what the antitrust laws prohibit. There were some successes in litigation, for which agency staff is to be commended. But a count of cases won or settlements gained as the only measure of a successful program would be a mistake. That approach can mask a great deal of inconsistency, inexplicable nonenforcement, inadequate settlements, and other wavering that, coupled with losses in litigation, has contributed to the deterrence crisis we are now facing.

We can best begin with a few examples where the agencies have done a good job of setting out their message and backing it up with litigation. At the FTC, three examples are the pay-for-delay,46 state action,47 and hospital merger48 cases. These are all examples of an agency strategically identifying a problem, consistently telling the public and the industry what it considered to be violations of the law, bringing cases that focused on the issue and underscored the harm involved,49 and ultimately making its point clear in litigation that culminated in favorable precedent.

Similarly, the treatment of so-called unilateral effects—the loss of direct competition between the merging firms—in the joint DOJ/FTC Horizontal Merger Guidelines, first in 1992, and then in 2010, demonstrates how contemporary economic thinking can be incorporated into agency guidance and accepted by the courts.50

These success stories have much in common. In each of these areas, success did not flow from the agencies, as it were, waking up one morning and filing a complaint. In each area, the agencies identified a problem, often after a judicial setback, and targeted it using multiple tools. They called attention to academic research, conducted their own studies, organized workshops, and engaged in public messaging designed to highlight a broader understanding of the problems involved. Stated differently, the agencies worked hard to win the battle in the marketplace for ideas as they were fighting in court. Those twin efforts may, in part, help explain some of the eventual litigation victories.

Indeed, what seems extraordinary, in retrospect, is not that the agencies made progress in these areas, but rather that their successes took so long and remain incomplete. In the case of pay-for-delay, 15 years passed from when the Federal Trade Commission first seriously investigated pay-for-delay deals until the Supreme Court’s 2013 decision in Federal Trade Commission v. Actavis, Inc. And the ground war over the proper interpretation of that decision is ongoing 7 years later.

The Antitrust Division can only claim mixed success in addressing most favored nation clauses. The division was successful in the United States v. Apple Inc. case involving the company’s price fixing of e-books. The agency also challenged Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan’s use of most favored nation clauses, alleging that they increased healthcare costs and prevented competition, after which Michigan passed legislation banning the challenged clauses before the case was resolved.51

The Antitrust Division’s case in U.S. v. American Express Co. turned out differently. Although the division and a group of state attorneys general won their challenge at the trial court, the Second Circuit and the Supreme Court rejected the case, creating arbitrary assumptions about platforms that could threaten future enforcement. In addition, the majority opinion entirely overlooks the entities that do the competing—credit cards—and thus does not even address the harm to competition put forth by the government.52

The Horizontal Merger Guidelines represent the agencies’ most explicit and important communication to the business community about the mergers they are likely to challenge; defending the guidelines is important to any deterrence program. As an example, the Antitrust Division defended the core of the guidelines in its successful challenges to two insurance mergers: Anthem Inc. and Cigna Corp., and Aetna Inc. and Humana Inc. in 2017.53 A failure to challenge those mergers would have reduced the number of major health insurers from five to three and left the business community with the strong impression that the concentration thresholds had little real, practical meaning.

Unfortunately, the agencies, over time, narrowed the range of transactions subject to investigation or challenge. In 2010, reflecting their own practices and the state of case law, the agencies raised the market concentration thresholds for presumptively anticompetitive mergers, to a level that focused enforcement on transactions that would leave no more than four equal-sized competitors post-merger even though those guidelines did stress the importance of actual effects of competitive harms as a means to demonstrate a merger’s anticompetitive impact.54 The economic literature suggests this level of merger enforcement is too lax and does not sufficiently deter mergers that lead to coordinated interaction.55

Recent studies suggest that too many anticompetitive mergers are occurring.56 Many challenged mergers are settled through consent decrees that require divestitures or impose temporary post-merger behavioral constraints on the firms. These too often suggest weak enforcement. The Federal Trade Commission also accepted divestitures in a series of transactions in which the buyers quickly went bankrupt.57 Although those settlements might reflect the weaknesses of the cases, they also are consistent with an agency too willing to settle.

Similarly, between 2005 and 2014, the Antitrust Division reviewed seven airline mergers. In five of those cases, there were no challenges, and the antitrust division settled the other two. Now, four airlines control almost 70 percent of domestic air travel in the United States.58 And in the case of the T-Mobile acquisition of Sprint, the Antitrust Division accepted a Rube Goldberg settlement to resolve a transaction that increased concentration well beyond the guidelines’ presumption of illegality. At best, the settlement traded the existing fourth competitor for a new, and almost certainly weaker, one in 7 years’ time, doing little to address the harms of the transaction to consumers.59

Over the past 20 years, the agencies also largely neglected vertical mergers. Official guidance was provided in the Non-Horizontal Merger Guidelines, which were issued by the Department of Justice in 1984. But these guidelines have been seen as a dead letter for years—for good reason. The agencies only sporadically enforced the antitrust laws against vertical mergers, leading to some settlements but no litigated decisions over the course of 40 years.

That was a mistake. This lack of enforcement contributed to a view that vertical mergers were unlikely to draw a challenge. Meanwhile, the economic literature increasingly rejects the view that all vertical mergers were procompetitive, based on making major conceptual advances since 1984. More recent empirical literature suggests an underenforcement problem regarding vertical mergers.60

By the end of the Obama administration, the Antitrust Division became increasingly concerned with vertical mergers and, despite settlements in a number of high-profile cases, was beginning to express skepticism regarding behavioral restraints as an effective remedy.61 The Trump administration seemingly built on this approach and challenged AT&T’s acquisition of Time Warner, refusing to accept a behavioral remedy.62

While there were good reasons to believe that the merger was anticompetitive, neither of the two antitrust agencies prepared any groundwork for a court challenge to a high-profile vertical merger. Furthermore, this case came with a number of unique challenges for litigation.63 The Antitrust Division lost both at trial and on appeal. This is not to say the agency was wrong to bring the challenge, setting aside the question of political interference.64 But it paid the price for both agencies having largely, although not entirely, abandoned vertical merger enforcement over the previous four decades.

The Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission did issue new Vertical Merger Guidelines in June 2020, but their impact was tarnished. Coming after the Antitrust Division’s 2018 unsuccessful challenge to the AT&T/Time Warner merger, the new guidelines were seen by many observers as an after-the-fact attempt by the Department of Justice to justify that challenge. The fact that two FTC commissioners voted against issuing the 2020 Vertical Merger Guidelines contributed to this perception. Others criticized the 2020 Vertical Merger Guidelines for not fully embracing the breadth of concerns that exist in vertical mergers. Although reasonable minds can disagree about whether guidelines should proceed or follow enforcement actions, choosing to litigate AT&T and Time Warner without laying the proper groundwork or distinguishing the case from the previous settlement, allowing Comcast to acquire NBC Universal Media LLC in 2011 was a poor strategy to reinvigorate vertical merger enforcement.

A very different problem is the tendency of the antitrust agencies allow individual losses in litigation to unnecessarily undermine their future enforcement. In the area of predatory pricing, neither agency brought a single case after the Antitrust Division lost its case against American Airlines nearly 20 years ago.65 While that loss was disheartening, it was also just the opinion of one panel of the U.S. Appeals Court of the Fifth Circuit, and need not have halted challenges to predatory pricing.

Instead, the Federal Trade Commission could have focused on investigating and litigating new predatory pricing cases administratively with the goal of achieving a better outcome when the defendant appealed. Likewise, in the merger area, for years, the Antitrust Division was extremely timid in challenging horizontal mergers after losing its challenge to Oracle Corp.’s acquisition of business software competitor PeopleSoft in 2004. The agency did not litigate a horizontal merger to a court decision for 7 years following that loss.

As a third example, both agencies were overly cautious about enforcing the antitrust laws relating to standard-setting and standard-essential patents following the FTC’s 2008 loss in Rambus Inc. v. Federal Trade Commission.66 Many believe that the Rambus case was wrongly decided. But the point here is that the opinion, centered on the causation standard under Section 2 of the Sherman Act, should not have deterred the agencies from policing abuses of standard-setting as established by prior precedent in the Allied Tube & Conduit Corp. v. Indian Head, Inc. case,67 the in the matter of Union Oil Company of California,68 and other cases.

Indeed, the few settlements obtained, the business review letters issued, and the joint statement by the Department of Justice and the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office were meaningful and well-reasoned.69 But they did not succeed in moving the case law forward. That made it possible for the Trump administration to largely reverse the progress that was previously made in the area of standard-essential patents by announcing policy reversals and successfully interfering in the FTC’s enforcement action against Qualcomm in 2019.70

The lesson here is that the agencies should not overreact to occasional losses in the courts when they have identified a practice that causes substantial consumer injury. Indeed, the Federal Trade Commission sustained multiple losses in the pay-for-delay cases until it finally won at the Supreme Court in Actavis. The agency also faced numerous setbacks in hospital merger challenges before it began to win and change the case law.

Ideally, if the agency is convinced in its cause and is confident in the evidence and theories of harm, it can narrow, if not reverse, a bad decision, or perhaps create a circuit split. The key is to adopt a strategic, intentional approach, which involves investing resources to find and bring the right test cases in areas where forward progress is realistic. Individual losses, especially those based on dubious reasoning, should not deter the agencies from pursuing clear instances of wrongful behavior.

Lastly, we reach the topic of antitrust enforcement against the tech platforms. The Microsoft litigation needs to be added to the list of successes, as one of the great enforcement cases over the past several decades.71 Its reputation has improved based on the premise that it helped clear the way for an enormous boom in web-based innovation following over the 2000s, the very “internet tidal wave” of which Microsoft then-Chairman and CEO Bill Gates had prophesied (and tried in vain to control). The Microsoft case also plays a role in unlocking competition in mobile telecommunications software and services.72 Even though the case law was, at best, unsettled at the time, a sound enforcement strategy led to a unanimous en banc decision of an ideologically diverse federal circuit court of appeals that established the importance of protecting potential competition.

But having established a firm policy of acting to prevent threats to a nascent competitor by an aggressive and domineering monopolist, the agencies did not, in the early 2010s, follow a similar policy when the major tech platforms were reinforcing their market positions through serial, nascent acquisitions. Hindsight, of course, is 20/20. Nonetheless, the fact that the agencies blocked none of the more than 600 acquisitions by dominant tech platforms and took an enforcement action against just one of them suggests the need for a serious re-examination of the interaction between merger control and the monopolization concerns of the Sherman Act.73

The recent report arising from the House Antitrust Subcommittee’s investigation of digital markets, the Antitrust Division’s October 2020 antitrust lawsuit against Google Inc., the November 2020 challenge to Visa Inc.’s acquisition of Plaid Inc., and the Federal Trade Commission’s investigation into Facebook Inc. are signs of such a re-examination. Antitrust enforcers should build on this re-examination and develop a strategic enforcement agenda to protect competition in digital markets.

In summary, while winning cases does matter, the antitrust agencies should take a broader view of law enforcement. They should be less concerned with the decisions of a few judges and more confident that, given a clear demonstration of harms, they can convince the country and the broader judiciary that their view is correct. That is why an enforcement agenda should not be tethered to the winning of individual cases, but rather should adopt a broader perspective on enforcement priorities and the pursuit of longer-term goals. That way, the agencies can either successfully improve the laws or clearly establish that Congress must intervene legislatively to repair the problem.

An important task for the new administration is to distinguish those areas of the antitrust laws where real progress can realistically be made through a well-directed and purposeful antitrust enforcement agenda from those areas where the law is so settled that Congress must legislate.

Civil enforcement agenda

There are a number of ways that the agencies could design an enforcement agenda for maximum impact. Three leading candidates would be to target industries where market power and anticompetitive activity is prevalent, specific harm or victims where it is substantial, or types of antitrust violations that are common. Any of these approaches, if pursued in a consistent and coherent fashion, could be successful. Ideally, an enforcement priority captures multiple goals. Sometimes doctrine and industry may combine to create an agenda, as in pay-for-delay cases in the pharmaceutical area. Or an agency might be concerned with policing harms to worker welfare in agriculture based on buyer-side consolidation and market power.

Alternatively, the agencies could adopt more than one approach, subject to the familiar proviso that to attempt to do too much could lead no results at all. Regardless of the approaches taken, coordination between the two agencies would enhance effectiveness, especially since a consistent message is critical for deterrence.

The industry-driven approach was pioneered by Assistant Attorney General Thurman Arnold in the late 1930s. Under his supervision, the Justice Department, aiming to break up cartels, targeted entire industries, sometimes filing hundreds of complaints in what he termed a “shock treatment” approach.74 Today, this approach would mean identifying industries widely understood to suffer from distinctive, chronic competition problems. These industries could be made an area of focus—not just for antitrust cases, but also for industry study and coordination with the appropriate regulatory agencies and Congress to work out the competition problems in the area.75 The industries selected need not be “sexy” or headline-grabbing. The problems in agriculture or meat processing, for example, may be worse than those in mobile communications.

The harm-based agenda takes, as an appropriate enforcement target, some form of economic harm that, for whatever reason, has been unaddressed by existing enforcement practice. Many antitrust experts argue that decades of prioritizing consumers and their welfare led to workers being neglected.76 This agenda might be driven by a new concern with a certain type of power, such as buyer-side market power in various U.S. labor markets.

The doctrine-driven agenda may sound unduly technical but focuses on the types of conduct that are problematic and looks to develop the legal doctrines courts apply. Under this approach, the agency identifies a doctrinal area where underenforcement or bad precedent seems to have led to clear harms. The developing of the structured-rule reason to assess inherently suspect restraints on competition and the overuse of the state action defense are examples of this approach.

There are a number of doctrines that the agencies could address. In mergers, the U.S. Supreme Court recognizes a presumption of illegality for mergers between competitors that substantially increase concentration in an already concentrated market, known as the Philadelphia Nation Bank presumption. In the half-century since then, courts have eroded that presumption, but they have not adopted any additional ones—even though the economics literature justifies additional ones. The agencies could advocate for presumptions for mergers of close competitors, mergers that threaten to harm innovation, mergers involving a maverick firm that constrains coordinated interaction, or mergers based on the prospect that the two merging firms may compete in the future.

In dealing with anticompetitive and exclusionary conduct, agencies could look to develop the law on most favored nations agreements, particularly in the context of digital platforms, given the growing theoretical and empirical literature on the harm they can cause.77 Similarly, refusals to deal, vertical restraints, competition in two-sided markets, and direct proof of market power are other potential areas for reform. In these areas, the existing doctrines often pose a challenge.

Choosing a test case also requires a strategic approach. When the agencies look to develop the law or limit the scope of existing precedent, it helps to bring a case where the harm is significant and obvious. This approach may mean passing on some cases to wait for a better one.

Government antitrust enforcers should not tilt at windmills. But they do have a responsibility to pursue cases and doctrine to the Supreme Court if the existing precedents allow substantial harm to go unremedied and will prevent the agencies from protecting competition in the future. This affirmative approach is risky, both because courts are skeptical of antitrust claims and because it is resource-intensive. The agencies should not adopt it lightly, and they cannot use it in every case. In targeted situations, a review by the Supreme Court may be critical for protecting competitive outcomes. While prevailing in such a challenge is the objective, even a loss at the Supreme Court would clarify the state of case law and make it apparent that only Congress can remedy the departure from legislative intent.

Using remedies to strengthen deterrence

The agencies need to consider the impact of any remedy on deterrence.78 Weak remedies can encourage additional anticompetitive conduct, and the government loses the precedential value of a litigated decision with a settlement. The government should not shy away from remedies such as break ups, compulsory licenses, and equitable monetary remedies where they are necessary to restore competition or prevent future anticompetitive harm. In those cases, the remedy itself both resolves the problem in the specific case and signals to companies that there are real consequences to violating the law.

There are, however, no hard and fast rules. A strong settlement may improve deterrence as much, or nearly as much, as a litigated decision. Like any litigant, the federal government needs to balance litigation risk in making decisions, but the government should not accept an incomplete remedy merely to avoid litigation. Although the factors determining whether to settle or litigate vary from case to case, the agencies do not appear to consistently weigh the importance of deterrence in their decisions on what remedy to seek and when to settle. The next administration should incorporate that consideration in its decision-making.

Criminal enforcement agenda

There is a clear and broad consensus in favor of vigorous criminal enforcement against cartels.79 Yet by any measure, cartel enforcement over the past 4 years fell dramatically. Compare the Obama administration (2009–16) to the first 3 years of the Trump administration (2017–19). Total criminal cases filed declined from an average of 60 per year in the Obama years to 23 in the Trump years, and the number of corporations charged averaged 20 per year under President Obama’s Department of Justice, compared with just eight per year by the Trump administration’s Department of Justice.80

At the same time, and perhaps relatedly, the Trump administration’s Antitrust Division abandoned a longstanding policy against allowing corporations to avoid criminal antitrust convictions for bid-rigging and price-fixing by entering into deferred prosecution agreements. That policy change, announced in July 2019, was selectively applied to large companies, mostly large pharmaceutical companies, while smaller companies are still required to plead guilty and suffer the consequences.81

All of this suggests the need for a fundamental review of current Antitrust Division cartel enforcement policy and procedure to ensure that cartel enforcement remains a priority and that justice is done fairly and equally.

Promoting competition as a federal government priority

For many years, domestic competition policy (with a few exceptions) was thought of as a function mainly centered in the Department of Justice’s Antitrust Division and the Federal Trade Commission. Those agencies, in turn, relied nearly exclusively on litigation to set policy. There are historical and statutory reasons for this approach.

Yet there are strong reasons to take a far broader, indeed a “whole government,” approach to competition policy in the United States.82 The administrative state, by necessity and because of the breadth of its regulatory ambit of so many federal agencies, already strongly influences the conditions of competition in many industries. Some agencies, such as the Federal Communications Commission, can enact rules specifically designed to catalyze competition. A pure litigation-driven approach has limitations, and in some instances, rulemaking has comparative advantages.

There are two broad ways to promote competition as a federal government priority. One is to establish a new White House Office of Competition Policy. Another is to engage in procompetition rulemaking. Let’s examine each in turn.

Establish a White House Office of Competition Policy

For these reasons, the next administration should establish a White House Office of Competition Policy within the Executive Office of the President that is led by the National Economic Council and includes membership from at least the Council of Economic Advisers, the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, the Office of Management and Budget, and the Domestic Policy Council. The tasks for this new office would be five-fold.

First, the new office would promote, throughout the federal government, the promulgation or amendment of rules designed to reduce barriers to entry, open industries to entrants, promote “truth in pricing,” improve the functioning of labor markets, or otherwise improve the functioning and competitiveness of markets.

Second, it would spearhead the legislative agenda described in this report and engage with relevant constituencies.

Third, it would coordinate action by the Department of Justice or the Federal Trade Commission and other executive branch agencies and independent regulatory commissions to tackle endemic competition problems in specific industries.

Fourth, it would monitor the rulemaking process so as to discourage or prevent rules that unnecessarily inhibit labor market mobility, market entry, or otherwise amount to anticompetitive uses of the regulatory state. Beyond that, it would seek to establish more coherent “whole government” competition policies in areas where the authority of agencies overlaps.

In these four ways, this new Office of Competition Policy would unify the next administration’s approach to competition policy and promote the importance of reinvigorated antitrust enforcement for consumers, workers, and marginalized communities.

Engage in procompetition rulemaking

Regulations often affect competition. Health and safety regulations, for example, can harm competition by protecting incumbent suppliers, or they can promote competition by facilitating entry by new, qualified suppliers. Regulation—and deregulation—is therefore an important tool to promote competition. History provides examples of procompetitive regulations, although regulatory agencies too often miss opportunities to promote competition. They also sometimes adopt rules that inadvertently or unnecessarily or intentionally undermine competition.

Existing examples of procompetition rulemaking

Some agencies of the federal government had success with so-called procompetitive rulemakings over the past several decades. The Federal Communications Commission provides some of the strongest examples. This agency’s rulemaking first broke the Bell Monopoly’s control over the home telephone market and also opened up competition in long-distance phone calls in the 1970s.83 Over time, the FCC’s rules not only yielded more competition in the provision of telephone handsets but also led to increased innovation in the attachment market, which had been carefully controlled by AT&T, including such technologies as the answering machine, fax machine, and the home modem, among other inventions.84

The Federal Communications Commission’s Computer Inquiries rules fostered the growth of an online services industry (lead firms such as AOL and CompuServe) and ultimately, the sale of internet services to the general public in the 1990s, a development with important consequences for the entire U.S. economy. The FCC’s number portability rules, which allow a consumer to bring along a phone number when switching carriers, was first enacted for landlines in 1996 and extended to wireless carriers in 2003. The rules did much to promote competition in telephone markets over the past two decades.85

The Federal Trade Commission also has the power to open industries to competition through rulemaking, though examples are scarce. Its 1977 eyeglass rule is a case in point. The agency’s Prescription Release rule, technically a consumer protection rule, can be credited with the rise of an eyeglass retail industry separate from prescribing doctors.86 That rule, and its requirement that patients be given a prescription, is an important precondition for the business model of firms such as Warby Parker, the online retailer of prescription eyeglasses.

To be sure, there also are examples of failed efforts to open industries to competition87 and of agencies that appear to be more interested in using regulation to close industries to new entrants rather than open them to competition.88 The ability of firms in an industry to limit or block rules that would otherwise intensify competition is a broad and significant contributor to the U.S. market power problem today. We do not suggest that procompetition agency rulemaking is easy or will easily solve all the nation’s competition problems. Yet the mixed record suggests the need to make sure competition concerns, not the financial interests of the firms themselves, are driving regulations.

The proposed White House Office of Competition Policy would pressure agencies to open up closed markets while discouraging agencies from entrenching the industries that they regulate. It would rely on its position within the National Economic Council and seek support from other agencies within the Executive Office of the President. It would serve as the fulcrum of a whole government approach to competition in a manner that is difficult for any individual agency to accomplish.

More agencies than can be listed here have statutory rulemaking authority that has a strong influence the conditions of competition in the industries they regulate and that, in some cases, includes a congressional mandate to improve the conditions of competition. A partial list of these agencies includes the Food and Drug Administration, the Department of Transportation, the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau, the Securities and Exchange Commission, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, the Federal Housing Finance Agency, the Department of Agriculture, and many others. These agencies are, in effect, already competition regulators, but it would be the task of the proposed White House Office of Competition Policy to ensure that they open markets wherever possible, maintain labor market mobility, and act to prevent entrenchment.

These agencies, of course, have other pressing priorities, such as protecting the safety of workers or working to control systemic risks. But these goals can be pursued in conjunction with competition. Because entrenched incumbent firms tend to have undue influence over sector-specific regulators, there is little doubt that the proposed new office would face resistance in many forms. But the new administration needs to find ways to push agencies to open competition in areas with endemic competition problems and to provide consumers with better information or better abilities to make informed choices.

Review of draft rules for anticompetitive effects

As it stands, the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, or OIRA, in the Office of Management and Budget reviews draft rules across the executive branch for their compliance with broader policies, including competition policy. A new White House Office of Competition Policy would participate in the OIRA regulatory review process, using its expertise to assist in reviewing draft rules with competitive consequences. This would strengthen a function already performed by the Council of Economic Advisers.