Problems in the U.S. care sectors risk holding back the economic recovery amid another month of disappointing job gains

According to the latest Employment Situation Summary by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the economy added 194,000 jobs in September—well below expectations and substantially less than the average 806,000 job gained over the previous three months. As the delta variant of the coronavirus sent ripples through the labor market, the prime-age employment-to-population ratio, or the share of 25- to 54-year-olds who have a job, remained flat at 78 percent between mid-August and mid-September. While the overall unemployment rate fell from 5.2 percent to 4.8 percent, some of the reduction in joblessness was the consequence of workers leaving the labor force.

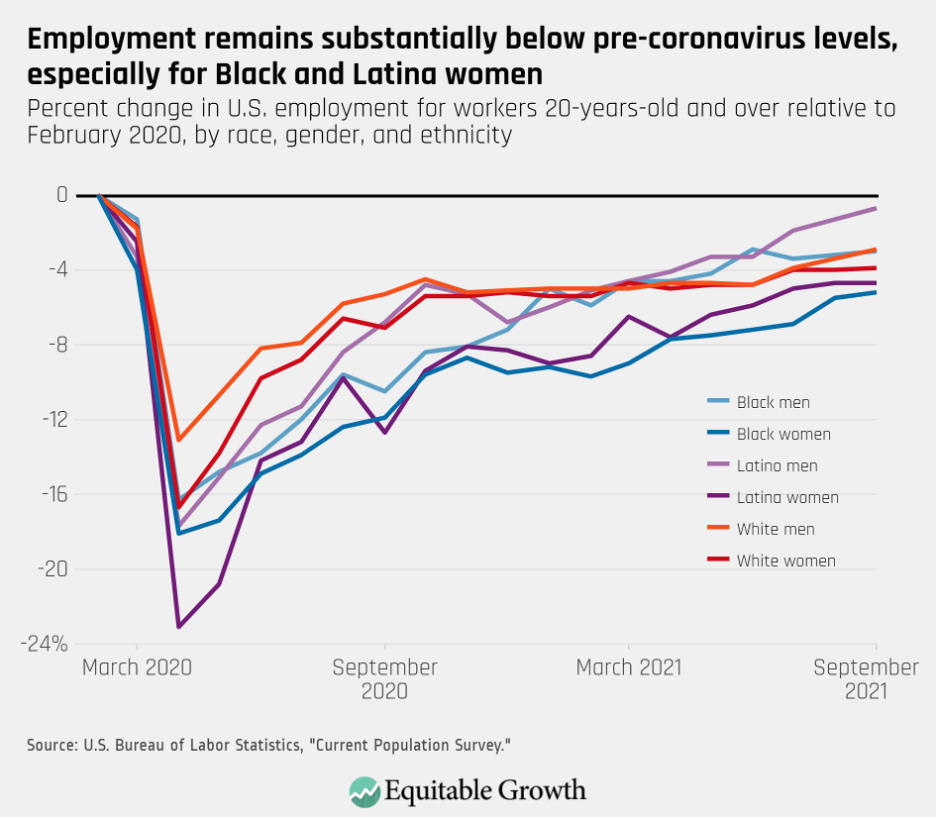

Today’s Jobs report continues to show that the recovery in employment remains uneven. Across the lines of race, ethnicity, and gender, employment is most depressed for women of color. In September 524,000 fewer Black women were employed than in February 2020, a decline of 5.2 percent. Latina women—who did not see any net increases in employment last month and face the second-deepest job losses—are experiencing a drop of 4.7 percent. (See Figure 1).

Figure 1

The still chilling effect of the delta variant was evident in overall job growth. The education and health care industry, for example, shed 7,000 jobs and the “other services” industry that includes sectors such as personal care services shed 16,000 jobs. Even though in September the leisure and hospitality sector added 74,000 jobs—more than any other industry—these gains still fell short of the massive number of jobs added during the summer.

Another factor holding back stronger employment gains is the slow recovery in some parts of the paid care economy. This sector provides health, education, and social services to workers, families, and communities.

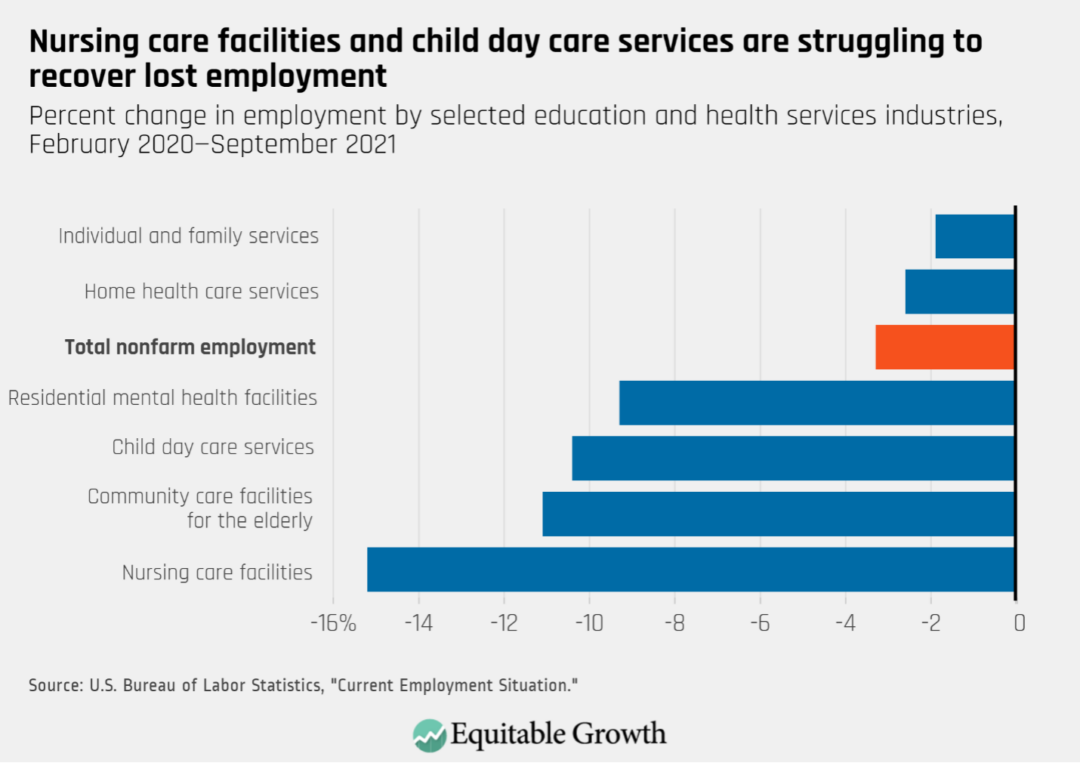

Indeed, last month nursing care facilities, residential mental health facilities, and community care centers for the elderly all saw their workforce shrink. These data reflect reports that care providers such as child care centers and nursing homes are struggling to hire and retain workers after millions of workers in the health care and social assistance industry were laid off between March and April of last year during the depths of the coronavirus recession. While some care sectors such as home health services have recovered at roughly the same pace as the overall U.S. labor market, others are lagging behind. As of September employment at nursing care facilities and community care centers for the elderly remained 15 percent and 11 percent below February 2020 levels. (See Figure 2).

Figure 2

One likely reason for the slow recovery in these care sectors is that the coronavirus pandemic made already challenging and often bad-quality jobs even more difficult. Compensated caregivers in general—among them home health aides, child care workers, and nursing home staff—tend to be poorly paid and are likely to experience precarious working conditions. In 2020, for example, the median wage for childcare workers was just $12.24 per hour and for home health and personal care aides just $13.02 per hour.

In addition, these workers often do not have access to employer-provided benefits and are often subject to particularly invasive forms of worker surveillance. And as the pandemic hit early last year, many of the workers who were not laid off were highly exposed to the coronavirus at work and often received little support from their employers in terms of provision of basic protective equipment such as masks. According to one analysis, nursing home workers held one of the deadliest jobs last year as they provided care in understaffed and underfunded facilities while also lacking access to paid sick leave and earning insufficient wages.

Because women in general and women of color in particular are overrepresented in care occupations, that care work is undervalued and thus is both a driver and a reflection of racial and gender economic inequality.

Bad-quality jobs in the care economy hurt workers, those who are in need of care, and the entire economy

There are broad implications of so many bad-quality care positions. Poor working conditions and low pay translate into high turnover rates among care workers—turnover that is expensive for employers and bad for clients and patients. Nursing home staff turnover was already extremely high before the pandemic, with an average annual turnover rate of 128 percent, and high turnover has been found to be associated with citations for poor infection controls.

This incomplete recovery in care-providing sectors also is a drag on employment growth and long-term economic growth. According to the U.S. Census’ Household Pulse Survey, more than 11 million adults are not working because they are caring for someone sick with coronavirus symptoms, caring for an elderly person, or caring for children who are not in school or daycare.

Then there’s the recent survey by the Urban Institute. It finds that in late 2020, about 20 percent of adults living with children under the age of 6 had to work fewer hours because of greater care responsibilities. More broadly, research finds that when parents in general and mothers in particular do not have access to affordable and high-quality child care, they are also less likely to be in the workforce.

Partly because of the country’s aging population and the labor-intensive nature of most of this kind of work, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projects that between 2020 and 2030, demand for home health and personal care workers will grow 33 percent—27 percentage points more than the average growth rate for all occupations. Also due to greater demand, five of the 10 fastest growing jobs are in care occupations. This means that the quality of jobs in the paid care economy will affect a growing number of U.S. workers in the years to come, making it increasingly important to act now to ensure that these are well-paying, good-quality jobs.

Investments in the U.S. care infrastructure are essential for a complete recovery and broadly-shared growth

The most direct route to start to counter the undervaluing of paid care workers is to raise pay through policies such as raising the federal minimum wage. Research by Krista Ruffini at the University of California, Berkeley, finds that because direct-care staff at nursing homes are some of the worst-paid workers in the United States, higher minimum wage floors lead to better labor market outcomes for those who do the job, reduce employee turnover, and improve patient care. Other measures that promote job quality, such as access to predictable schedules and safe working conditions, also are essential.

Because the U.S. labor market continues to be short 5 million jobs compared to the abrupt end of the previous economic expansion in February 2020, investments in U.S. care infrastructure will be essential for reaching a complete and resilient recovery.

Insufficient investment in accessible and high-quality child care and home- and community-based services have long held back progress toward a more dynamic and equitable economy—one in which paid caregivers are fairly compensated and those who currently cannot do paid work because they have caregiving responsibilities are able to enter the workforce if they choose to.