Worthy reads from Equitable Growth:

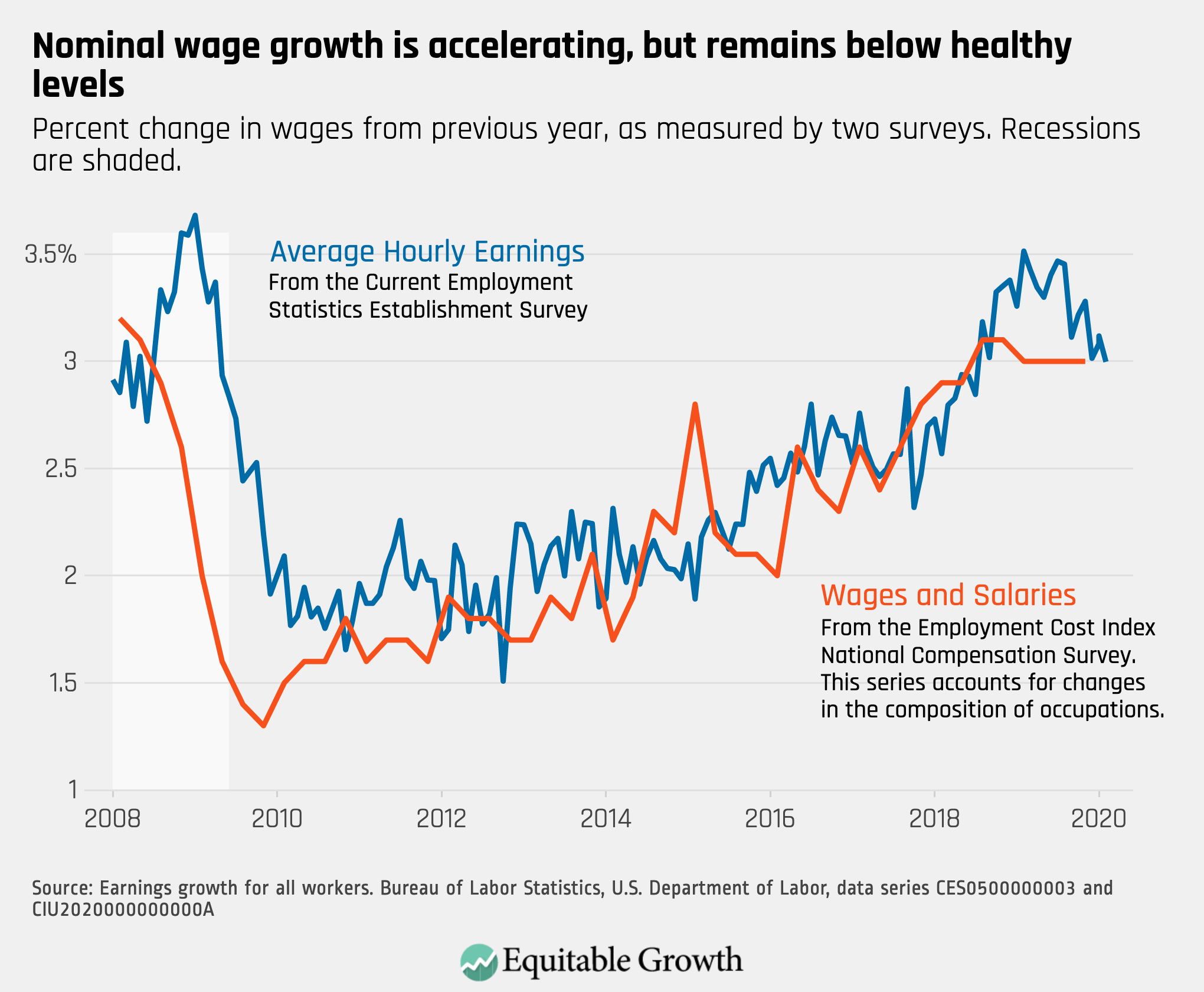

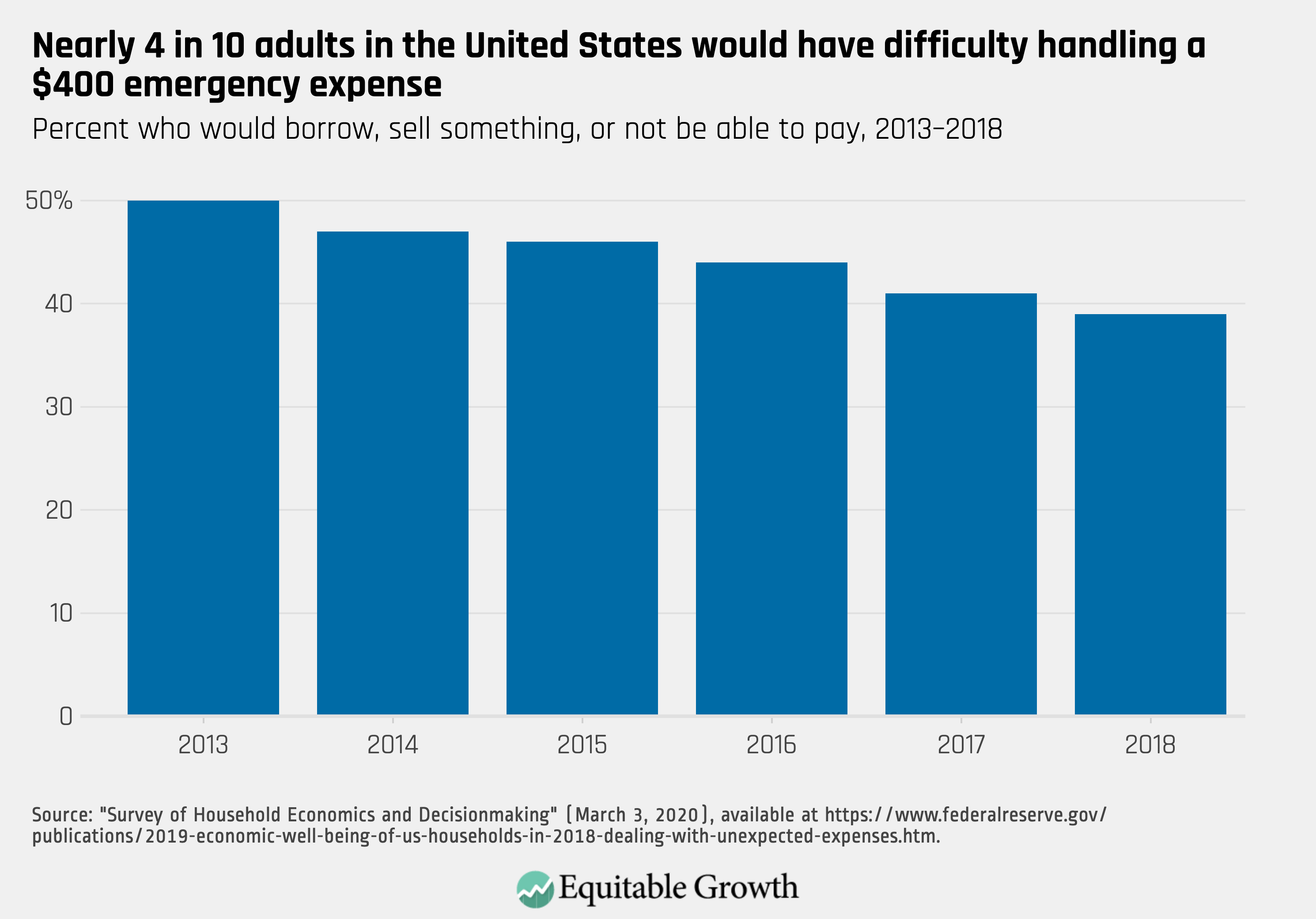

- The Federal Reserve appears to be not just the first but the only instrumentality of the federal government to actually do something significant in response to the coronavirus. Since this is overwhelmingly not a monetary policy problem but rather a public health problem, this is really, really, really, really not how things should be. Read Claudia Sahm, “U.S. economic policymakers need to fight the coronavirus now,” in which she writes: “The Fed[‘s] … policy tools … are too blunt to help the people who need it most. People in our country are getting sick, and the most vulnerable workers could lose their jobs if they are too ill to show up. Monetary policy cannot address this gaping public health problem. Yes, the Fed might calm financial markets some. Yes, the Fed might help businesses and borrowers who are taking on debt. The Fed is doing its part, doing what it can. But it needs help. Chair Powell made that clear before the cameras, saying: ‘The virus outbreak is something that will require a multifaceted response. And that response will come in the first instance from healthcare professionals and health policy experts. It will also come from fiscal authorities, should they determine that a response is appropriate. It will come from many other public- and private-sector actors, businesses, schools, state and local governments … This morning’s G-7 statement … reflect[s] coordination at a high level in a form of a commitment to use all available tools.’ What can the federal government do? Here is my proposal, grounded in more than a decade of research and forecasting at the Fed. Act fast. It is time for the federal government—all parts of it—to move swiftly against the spread of the coronavirus and any economic distress it may cause … [p]rovide financial support to people who are suffering … [p]lan for the worst … [h]ave automatic support ready for a recession.”

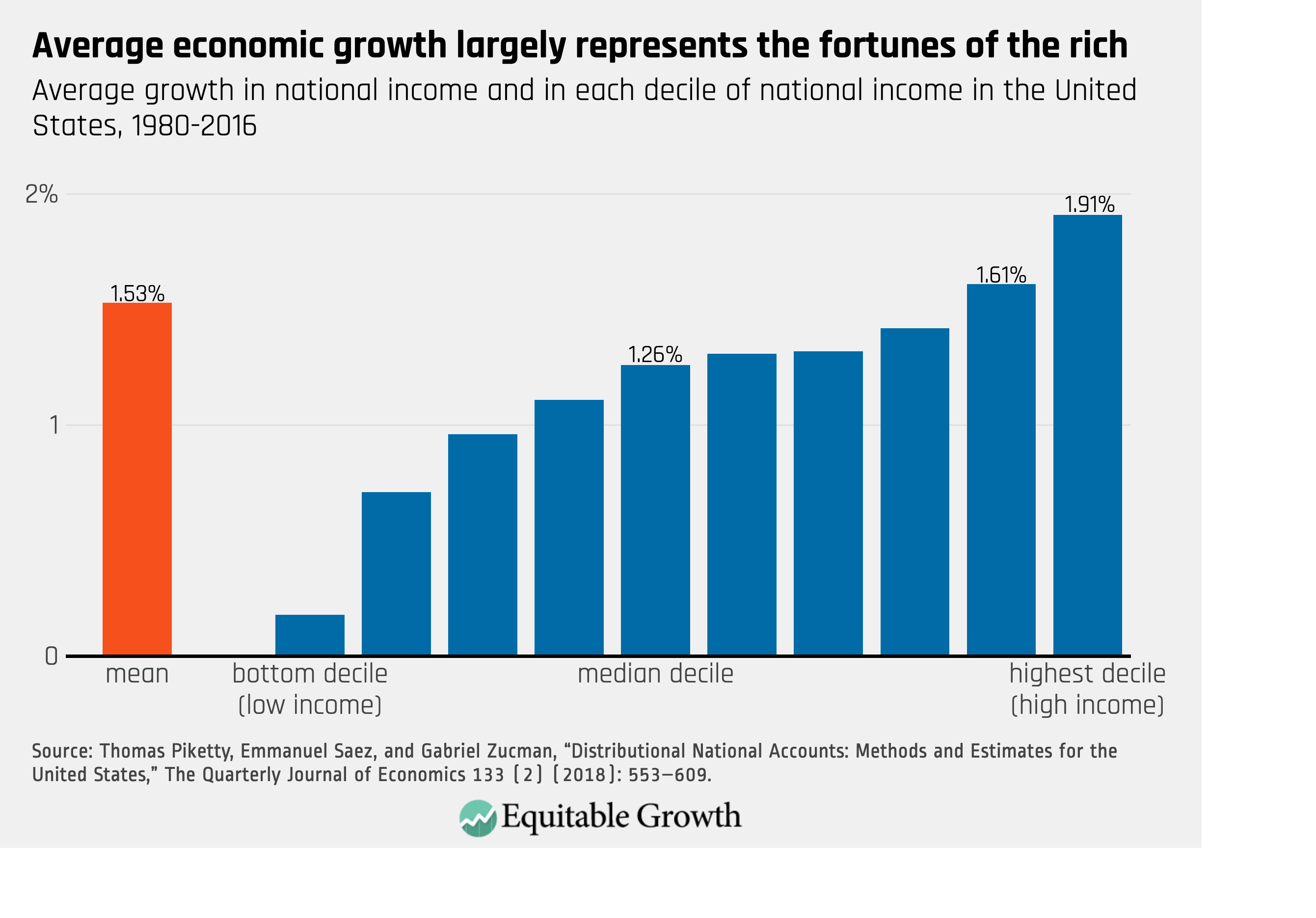

- This looks to be a major advance in our ability to track in near real time the regional evolution of the U.S. economy. If I had seen this pattern of regional growth and decline a decade ago, it would have made me less worried about the gerrymandering that the Constitution has built into the Senate. The people in declining areas are relatively poor, and they have little economic or cultural power, so giving them more political power might have created a fairer overall balance. Yet somehow it does not seem to have worked out that way. Their senators are not fighting for a fairer division of wealth, but seem focused on achieving negative sum goals for the country at large—if we can’t be prosperous, you shouldn’t be prosperous either. Read Raksha Kopparam, “County-level GDP gives insight into local-level U.S. economic growth,” in which she writes: “The U.S. Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Economic Analysis released a new measure … Local Area Gross Domestic Product. LAGDP is an estimate of GDP at the county level between the years of 2001—2018 … Growth since the end of the Great Recession in mid-2009 … is concentrated in the West Coast states and parts of the Midwest. States such as Nevada, West Virginia, New Mexico, and Wyoming have seen a significant number of counties contract in economic output since the recession. One of the benefits of this new LAGDP measure is that it provides an industry-specific breakdown …[t]rends in the manufacturing industry and how manufacturing has contributed to GDP pre- and post-Great Recession are also now more trackable … Manufacturing… [in] clusters of counties on the East Coast and the Midwest suffered contractions. Although overall manufacturing output in North Carolina increased, many counties experienced heavy declines over the past 17 years … 20 percent of the nation’s economic growth is concentrated in 11 counties, including the cities of Los Angeles, New York, and Harris, Texas.”

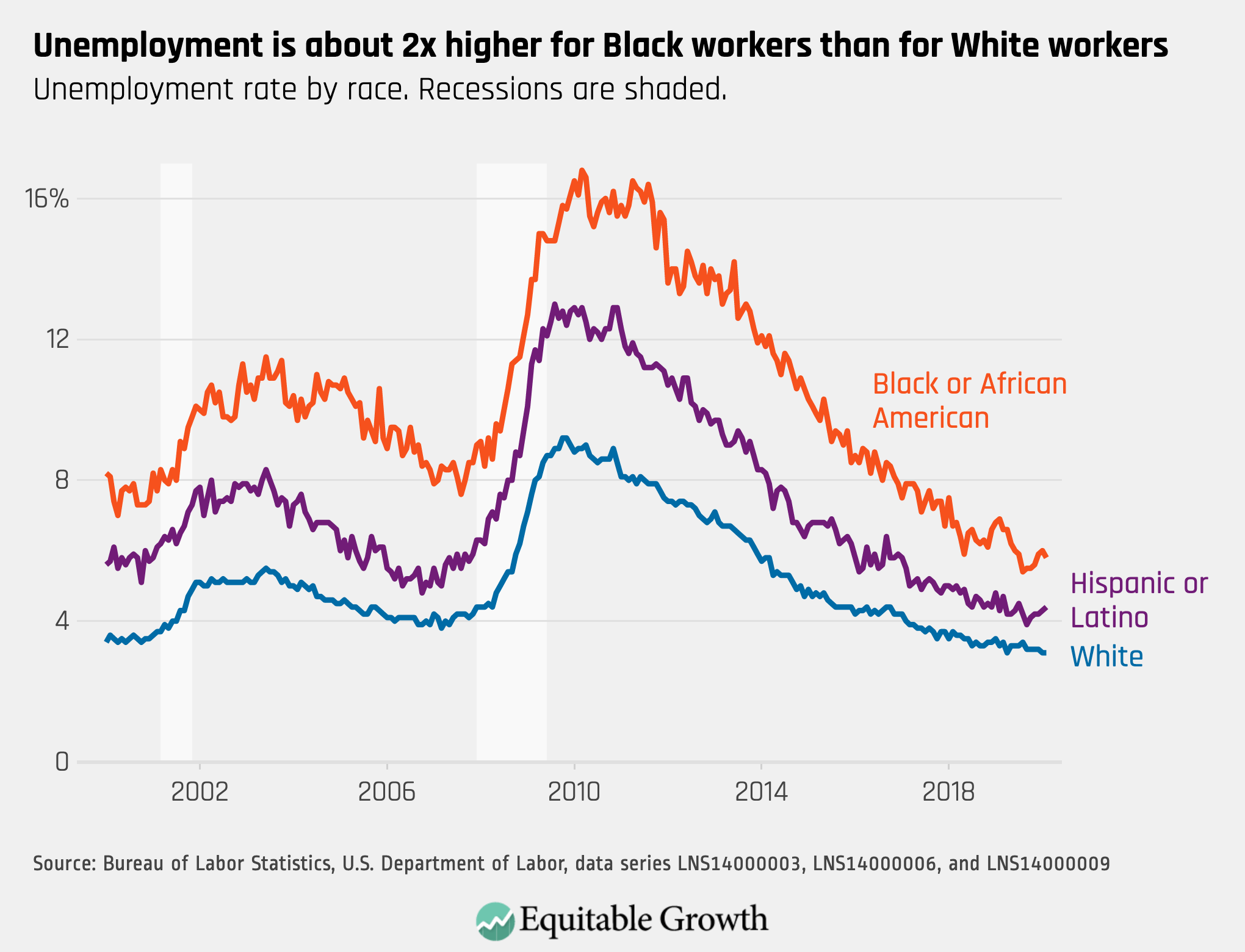

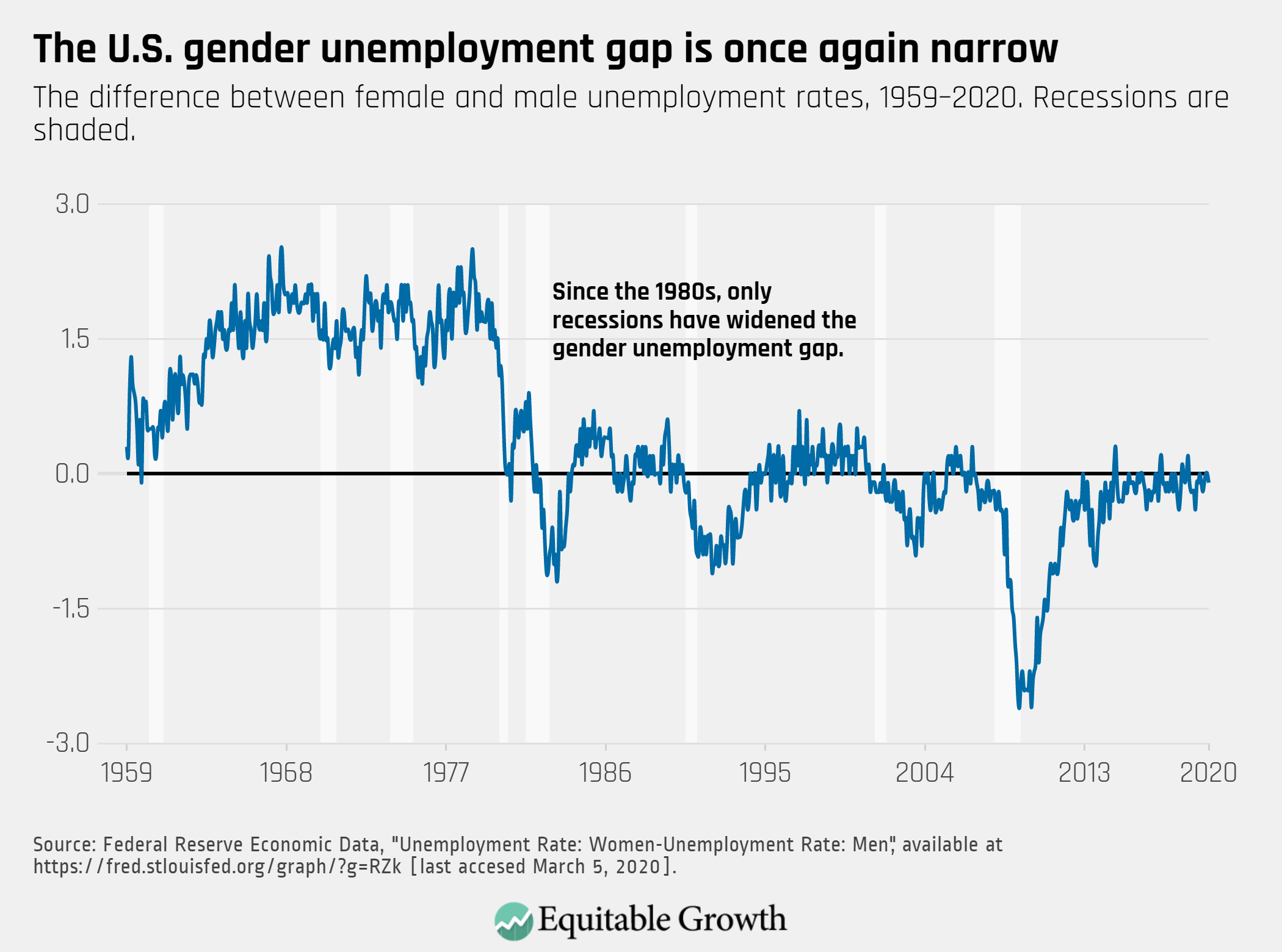

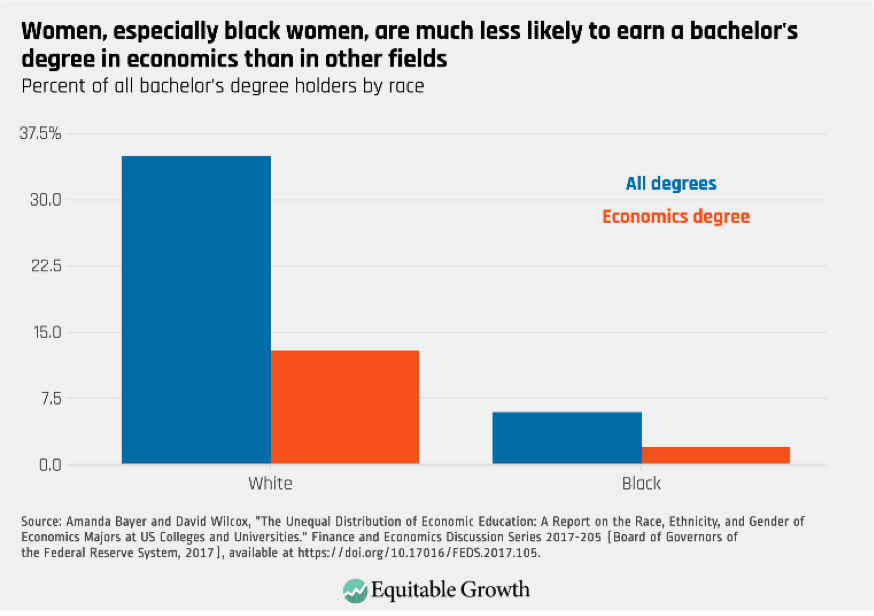

- Young whippersnapper Carmen Sanchez Cumming joins Equitable Growth, and sets to work. Read her “What the historically low U.S. unemployment rate means for women workers,” in which she writes: “Last month’s Jobs Report showed that at 3.5 percent, the share of women who are actively looking for a job but don’t have one continues to be near a 65-year low. At 3.6 percent, men’s unemployment rate is currently slightly above the rate for women. Prior to 1983, that was rarely the case. Research published in 2017 by economists Stefania Albanesi of the University of Pittsburgh and Ayşegül Şahin (at the time with the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and now at the University of Texas at Austin) shows that for most of the post-World War II period and until the early 1980s, women’s unemployment rate was rarely below 5 percent and usually more than 1.5 percentage points above that of their male counterparts. In the ensuing four decades, however, the gender unemployment gap—the difference between the female and male unemployment rates—nearly disappeared except during recessions, when men consistently experience a higher joblessness rate.”

Worthy reads not from Equitable Growth:

- This is a remarkably large effect. If it holds up, it indicates not just that there are huge benefits to air filters in schools, but that there are huge societal losses from other forms of pollution as well—and that we ought to be spending a lot more on pollution control than we are: Matthew Yglesias, “Installing air filters in classrooms has surprisingly large educational benefits,” in which he writes: “An emergency situation that turned out to be mostly a false alarm led a lot of schools in Los Angeles to install air filters, and something strange happened: Test scores went up. By a lot. And the gains were sustained in the subsequent year rather than fading away. That’s what NYU’s Michael Gilraine finds in a new working paper titled “Air Filters, Pollution, and Student Achievement” that looks at the surprising consequences of the Aliso Canyon gas leak in 2015. The impact of the air filters is strikingly large given what a simple change we’re talking about. The school district didn’t reengineer the school buildings or make dramatic education reforms; they just installed $700 commercially available filters that you could plug into any room in the country. But it’s consistent with a growing literature on the cognitive impact of air pollution, which finds that everyone from chess players to baseball umpires to workers in a pear-packing factory suffer deteriorations in performance when the air is more polluted. If Gilraine’s result holds up to further scrutiny, he will have identified what’s probably the single most cost-effective education policy intervention—one that should have particularly large benefits for low-income children. And while it’s too hasty to draw sweeping conclusions on the basis of one study, it would be incredibly cheap to have a few cities experiment with installing air filters in some of their schools to get more data and draw clearer conclusions about exactly how much of a difference this makes.”

- Martin Wolf is usually measured. Martin Wolf is now fearing that the possibility of keeping global warming a mere catastrophe rather than something much worse is slipping out of reach. Read Martin Wolf, “Last chance for the climate transition,” in which he writes: “At the World Economic Forum in Davos this year, two people stood out: Greta Thunberg, the 17-year-old Swedish climate activist, and Donald Trump, the U.S. president. In their messages on climate change, these two could not have been more opposed: panic, confronted with indifference. But one thing they share is that they are not hypocrites: Ms. Thunberg does not pretend we are doing anything relevant; Mr.Trump does not pretend he cares. Most participants in the climate debate, however, pretend to care, pretend to act, or both. If anything is to be done, this must change. Ours remains what it has been since the early 19th century: a fossil-fuel civilization. There have been two energy revolutions in human history: the agricultural revolution, which exploited far more incident sunlight; and the industrial revolution, which exploited fossilized sunlight. Now we must return to incident sunlight—solar energy and wind—along with nuclear power, while maintaining our high standards of living.”