Part of the story of why income and wealth inequality is rising is tied to the decline in the bargaining power of organized labor over the past half-century. That decline is the result of multiple complementary forces, but one of the biggest and most illustrative is the dramatic shrinking of the unionized workforce.

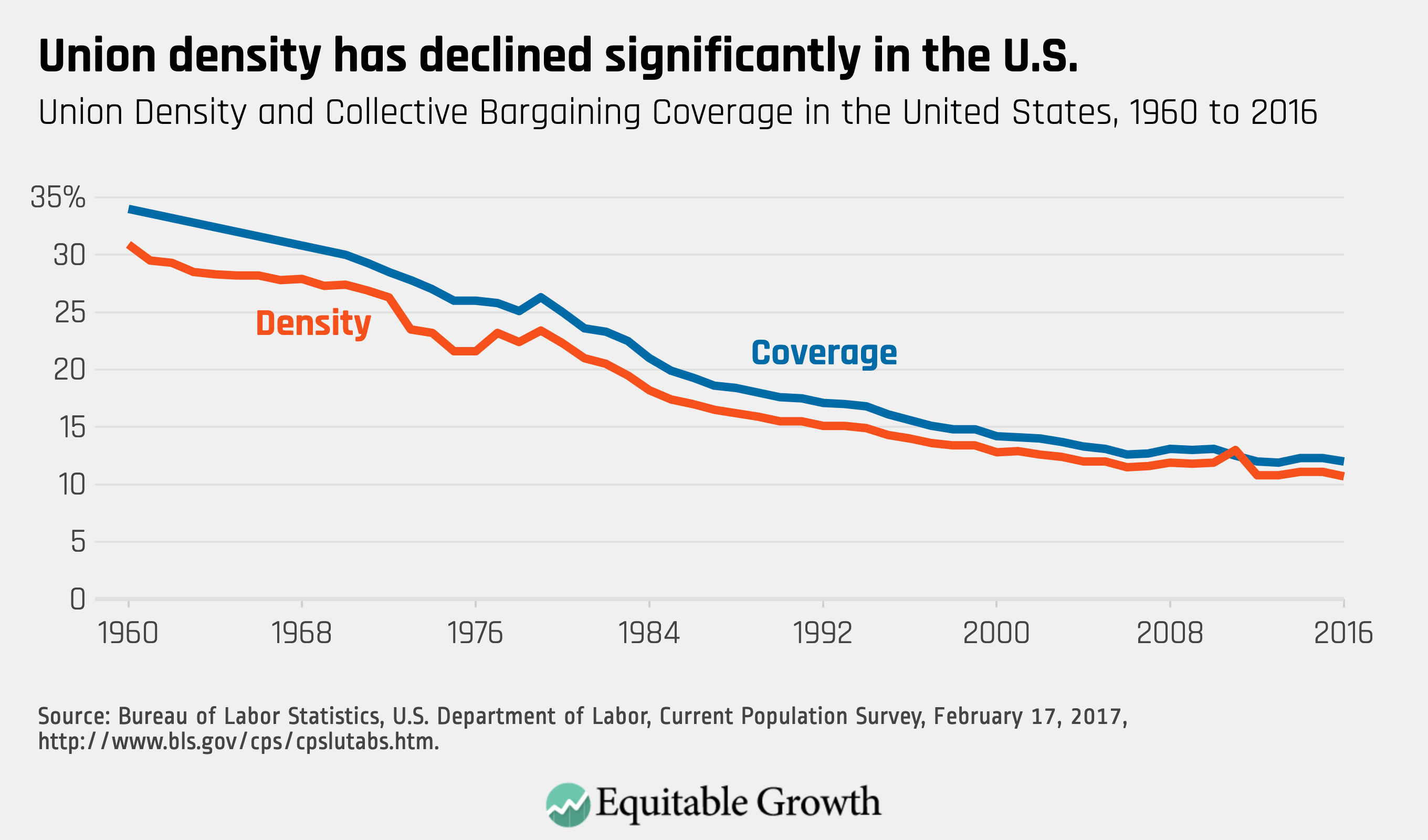

Two important indicators, union density and collective bargaining coverage, highlight the severity of the decline. Union density is the proportion of workers who are members of a union. Collective bargaining coverage is the proportion of workers covered by a collective bargaining agreement regardless of whether they are members of a union. Both have been dropping for decades, and those levels pale in comparison what we observe in other countries with similar standards of living as the United States.

From 1960 to 2016, the union density rate fell by more than half. In 1960, nearly one in three workers was a union member. According to the most recently released annual data from the U.S. Department of Labor’s Bureau of Labor Statistics, that number is down to just over one in ten. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

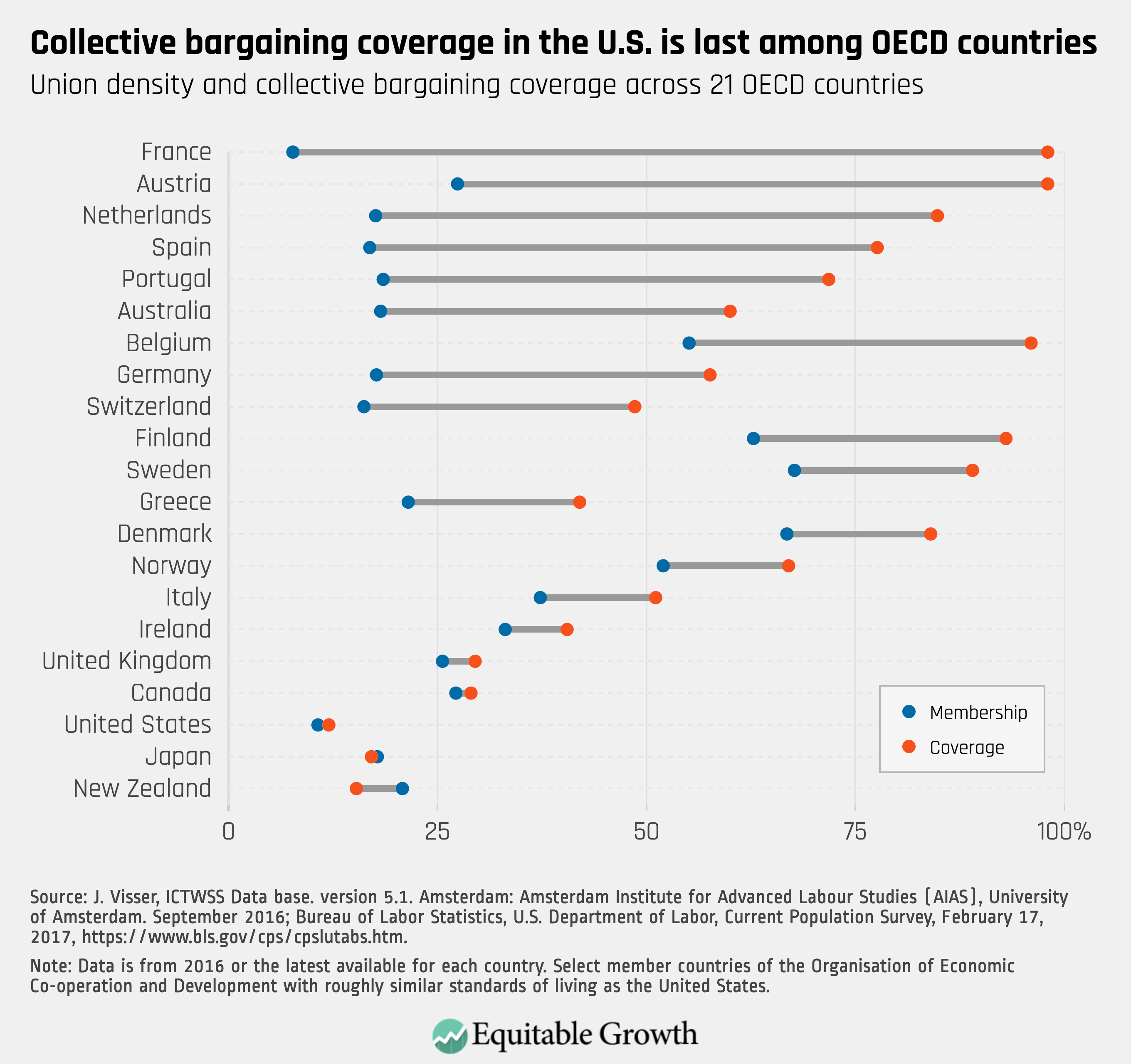

International comparisons shed some important light on the U.S. experience. It’s immediately obvious from comparing union density and coverage data assembled by Jelle Visser at Amsterdam Institute for Advanced Labour Studies that labor market institutions vary dramatically across a range of economies with a roughly similar standard of living as the United States. Among 21 member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the United States is 20th in union density, coming ahead of only France. Interestingly, though, France is tied for 1st with Austria in collective bargaining coverage. On that measure, the United States is last. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

In many OECD countries, including France as mentioned above, there are striking magnitudes of difference between union coverage and density rates. In the United States, a worker might not be a member of a union but nonetheless may be covered by a collective bargaining agreement since by law a union must represent all workers at a firm, even those who decline to join the union. Elsewhere though, as in many of these high-coverage countries, there might not be a single union member at a firm or even a contract that was negotiated at the firm level, but nonetheless those workers are covered by a collective bargaining agreement that was negotiated by representative unions across employers in most or all of the industry. Levels of union coverage observed in these countries are the result of more union-friendly legal frameworks and in some cases the administration of social insurance by unions, among other things.

Beyond instances of very high coverage levels, there are noticeable differences, for example, between countries with similar institutional arrangements. In the United States and Canada—where collective bargaining coverage within unionized firms is 100 percent and 0 percent within non-unionized firms—there is a much smaller difference between density and coverage rates. In Canada, the gap between union density and coverage is 1.8 percentage points, only slightly larger than the gap in the United States, but overall both density and coverage rates are significantly higher in Canada than in the United States.

So why might it be the case that these two neighboring countries exhibit such a dramatic difference in density and coverage? Part of the reason is the process by which workers at individual firms unionize. Modest policies that are more favorable to union formation and recognition, such as majority sign-up and first contract arbitration, can be very consequential for boosting worker power in circumstances similar to those found in both countries.

In terms of policy here in the United States, organized labor has been on the losing side of those important battles for a long time. There are now 28 “right to work” states and the political opposition to collective bargaining is intense at the federal level as well. But going forward, it’s important to keep in mind the international context. There is tremendous policy variance between the countries shown above. That variance must be thoroughly explored and considered if we’re going to make progress in bolstering the bargaining power of labor and reversing the current trend of worsening inequality.