Business investment in the United States has been disappointing this century compared with the amount of profits that companies have pulled in. Since 2000, the amount of business investment is significantly below where economists and financial market analysts might expect given the level of profits. Could this perhaps be just a benign trend? After all, the U.S. population is getting older, and perhaps the economy just needs less investment. The same could be said if the trend is due to cheaper capital goods. But new research suggests that a more malignant force may well be behind weak investment growth—declining competition.

The new paper by economists Germán Gutiérrez and Thomas Philippon of New York University is a follow-up to their paper from late last year. The earlier paper documented the divergence between investment and profits, detailed why the trend was significant, and tried to figure out roughly what was behind the investment decline. Their results suggested that a lack of competition in the U.S. economy was a primary driver. Their new paper looks for evidence of a causal relationship between competition and investment.

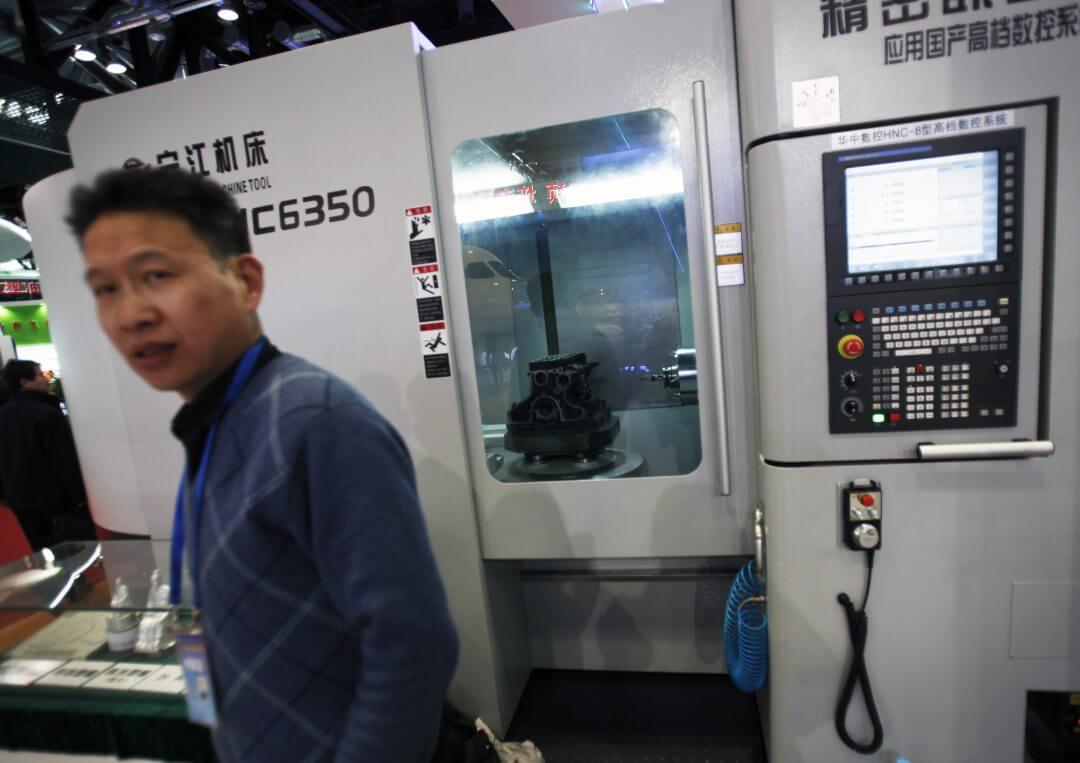

One of the potential problems with trying to show that one thing causes another with econometrics is that researchers often face a trade-off between results that show clear causal links and results that are likely applicable to other cases. Gutiérrez and Philippon face such a dilemma here but end up choosing both options. They employ a so-called natural experiment where the entrance of competition from China changed investment decisions in the manufacturing sector, which is likely to generate clear results. The two economists then ran an analysis that looks at how more firms entering an industry than expected affects competition and then investment. This technique isn’t going to be as crisp or clear as a natural experiment, but it’s likely to be a general result that holds up in a number of cases.

In both cases, the researchers find a causal link between competition and investment. The increase in competition resulting from increased Chinese manufacturing imports led to increased investment among leading firms facing this overseas competition. Industries that saw more “excess entry” also were the industries that showed rising investment. Furthermore, other research by Gutiérrez and Philippon shows that investment in the United States is weaker than in Europe, where competition is higher. The case that declining competition is causing, at least in part, the reduction in investment growth seems quite strong.

If this is the case, then the question is: What’s causing this decline in competition? The two economists look at three potential explanations: increasing regulation; the rise of “superstar” firms; and an aging U.S. population. They find a fair amount of evidence for the role of regulation, slightly less for superstar firms, and not much evidence at all for changing demographics.

Pointing to regulation as the chief culprit is only the start of an answer to this important question. It sparks other queries, such as what kinds of regulations are harming competition. And what about the role of enforcement? This is a factor that the authors discuss but don’t look at in the data. This paper is an important start for highlighting and thinking through the role of declining competition in reducing business investment. Let’s hope it’ll cause academics and policymakers to align to spend more time and resources investigating this problem.