Jobs Report: U.S. employment growth slowed in December, with the leisure and hospitality industry far from recovered

U.S. employment growth was much weaker than most estimates expected in December, according to the latest Employment Situation Summary by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Data collected the first half of December and released today shows the U.S. economy added 199,000 jobs—well below the previous three-month average of 425,000 jobs gained. Notably, this data represents employment data from immediately before the extreme rise in U.S. COVID-19 cases fueled by the highly contagious omicron variant of the coronavirus in mid-December.

The overall unemployment rate continued to decline to a new pandemic low, falling from 4.2 percent in November to 3.9 percent in December. The country’s labor force participation rate, however, remained at 61.9 percent, and has experienced little improvement since mid-2020.

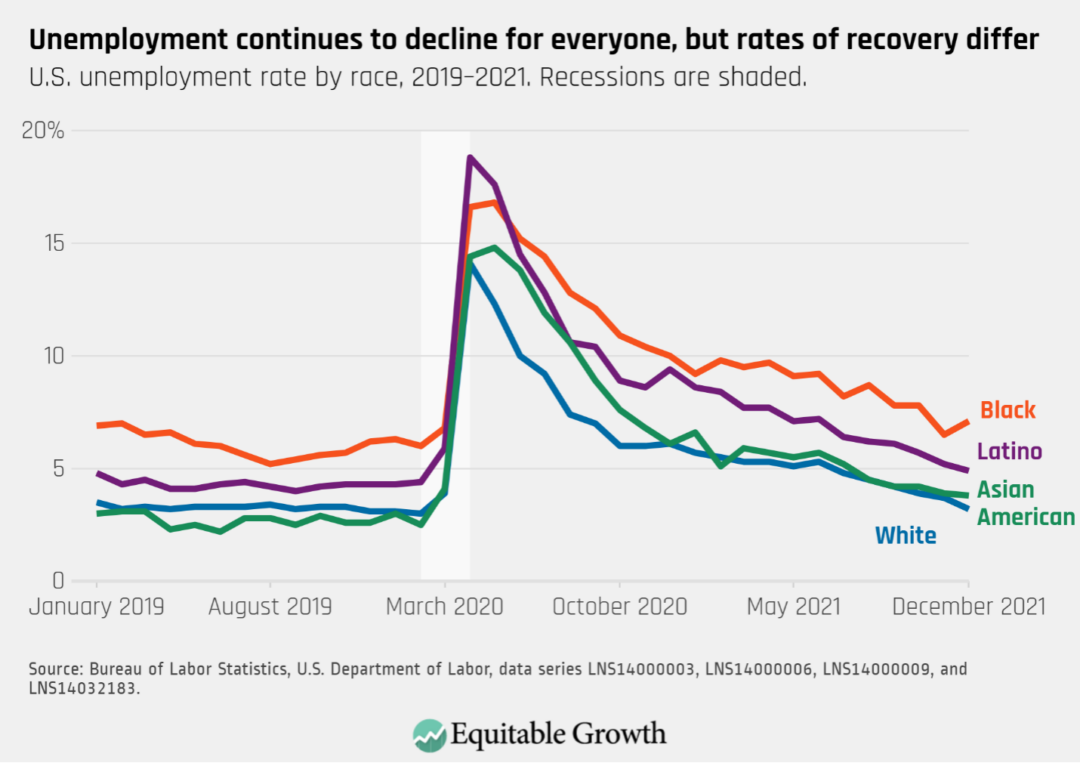

For some groups of workers the recovery has been much slower than for others. Black workers were the only group of workers to see their unemployment rate rise, climbing from 6.5 percent in November to 7.1 percent in December. Latino workers are experiencing an unemployment rate of 4.9 percent, Asian American workers of 3.8 percent, and White workers of 3.7 percent. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Some workers also are experiencing especially longer periods actively looking for jobs without success. Unemployed Black workers and Asian American workers are experiencing an average of 33 weeks of unemployment, compared to 25 weeks for Latino workers and White workers.

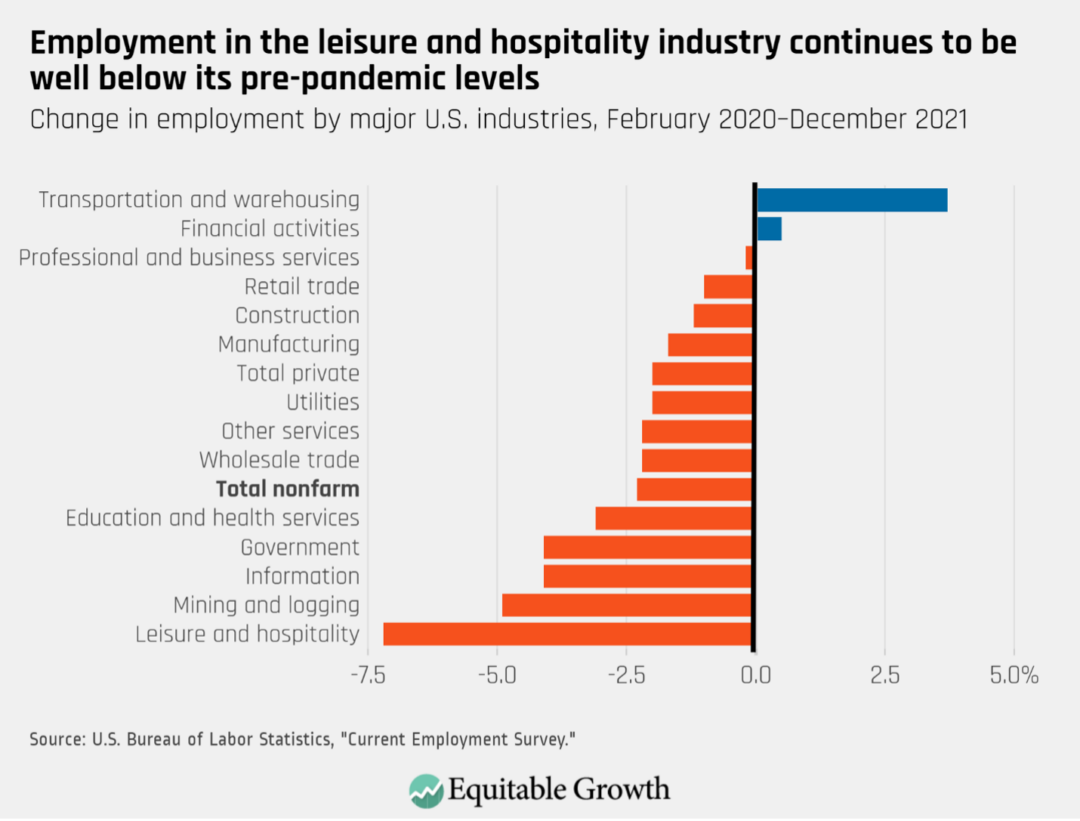

Across industries, the now 18-month-long economic recovery remains uneven. Employment in the financial activities and transportation and warehousing sectors, for instance, is now above its pre-pandemic levels. But employment in the leisure and hospitality industry—one of the largest major sectors in the country—continues to be more than 7 percent below where it was in February 2020. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Indeed, no other industry has experienced as much volatility during the coronavirus pandemic as leisure and hospitality. Most jobs in the industry cannot be done remotely, and many establishments closed or saw a sharp reduction in business at the onset of the health and economic crises. The leisure and hospitality industry lost almost half of its total jobs in early 2020 as employment plummeted from almost 17 million jobs in February 2020 to less than 9 million jobs in April 2020, while the sector’s unemployment rate skyrocketed to 39.3 percent.

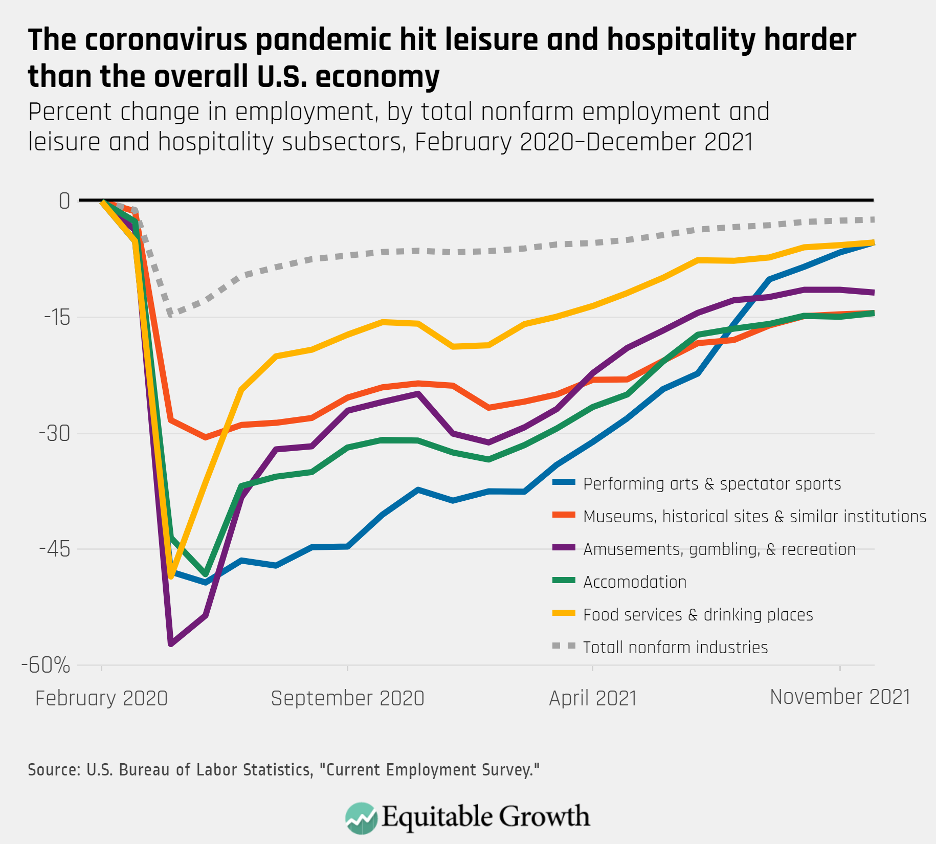

Recovery within the leisure and hospitality industry is still uneven, as different subsectors are affected by changing consumer behavior and public health safety measures amid the ongoing pandemic employment in the food services and drinking establishments subsector initially fell by almost half, but since mid-2020 recovered at nearly pre-pandemic levels. Likewise, the amusements, gambling, and recreation subsector of the industry experienced the steepest decline in employment at the outset of the pandemic, but now has recovered most of its lost jobs. The performing arts and spectator sports subsector was slow to recover from its initial dramatic losses, but has largely rebounded in recent months.

One area where employment remains farthest below pre-pandemic levels is museums and historical sites. This subsector did not experience as dramatic a loss in initial employment as other areas, but today it has yet to regain half of the jobs it lost during the pandemic—potentially due, in part, to a decline in donations and revenue from ticketing combined with greater additional operation costs due to new safety measures. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

Even these dramatic employment trends do not fully capture the level of volatility that leisure and hospitality workers continue to experience. Many workers suffered through sudden losses of income due to pandemic-related closures even when employed. For instance, in May 2020—the first month such data is available—more than 40 percent of leisure and hospitality workers were unable to work at some point in the past month because their employer closed or lost business due to the pandemic, with the vast majority (89 percent) reporting they did not receive pay for the lost hours.

Before the pandemic, many leisure and hospitality industry workers already faced low pay and bad working conditions

These pandemic-related disruptions faced by many leisure and hospitality workers only compounded already low pay and bad working conditions in the industry. This is a problem for the U.S. economy because the leisure and hospitality industry employs about 1 in 10 workers. And the industry disproportionately employs women and workers of color, especially in accommodation, where 59 percent of workers are women, 26 percent are Latino, and 17 percent are Black.

With average hourly earnings of only $19.20 an hour for an average 26.4 hours per week, leisure and hospitality is the worst paying industry in the U.S. economy. These low wages are accompanied by poor job quality across the board, including unpredictable schedules, high rates of labor law violations such as wage theft, and a lack of benefits. Only one-third (32 percent) of wage and hour employees in this sector, for example, have access to employer-sponsored health care, and just half (50 percent) have access to paid sick leave—even in the midst of a global pandemic. Unpredictable schedules and low pay also make it difficult for workers to secure child care and navigate transportation challenges.

Because of this poor job quality, and the sensitivity of leisure and hospitality firms to seasonal fluctuations and shifts in economic conditions, job turnover has typically been significantly higher in leisure and hospitality (79.0 percent annually in 2019) compared to the overall private industry (45.1 percent).

But there are signs that leisure and hospitality industry’s workers are improving their livelihoods by switching jobs or exiting the industry amid the pandemic

Amid the ongoing coronavirus crisis, the leisure and hospitality industry became even more volatile—and dangerous—in turn sparking workers to seek better pay and working conditions outside of the industry. As the pandemic hit, those who kept their jobs had to work in high-risk conditions, often without employer-provided personal protection equipment. A study using data from the California Department of Public Health, for example, found that cooks, maids and housekeepers, and bartenders were among the occupations in which mortality rose most during the coronavirus pandemic.

Many factors appear to play a role in the industry’s lagging recovery and difficulty retaining workers, including workers’ fear of contracting or spreading the coronavirus, a reassessment of career trajectories, the industry’s low compensation and bad-quality conditions, and a lack of accessible childcare that is likely disproportionately affecting women-dominated industries. These dynamics are all compounded by ongoing uncertainty about the trajectory of the pandemic that is still dampening demand, especially in sectors such as travel, and the shift of consumer spending from services to consumer goods.

While employment levels overall in the U.S. economy have not yet rebounded to pre-pandemic levels, nominal wages have risen over the past few months for workers in low-wage industries, among them leisure and hospitality workers. The Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, another government survey, shows that both the number of quits and job openings in the industry broke previous record highs this summer and are substantially above their pre-pandemic levels, which typically is also considered a positive sign for workers’ confidence in the U.S. labor market.

Some leisure and hospitality workers appear to be moving into higher-paying jobs within leisure and hospitality, and others are exiting the industry for other opportunities. Such moves were already common among food and accommodation workers (a subsection of leisure and hospitality workers): A pre-pandemic analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data by Indeed.com’s Hiring Lab found that in early 2018, about half of food and accommodation workers who switched jobs stayed in food and accommodation, and about half moved to a job in another industry. The most common destination for those who left food and accommodation was retail trade, accounting for 13.0 percent of all job-switchers from that industry.

The present historic rate of jobs churn the industry is experiencing likely reflects both a continuation of pre-pandemic dynamics within this volatile low-wage industry and new labor market movements as workers seek more livable wages and working conditions after nearly two years of heightened uncertainty and stress. As employers in the leisure and hospitality industry report struggling to hire and retain their staff, dynamics in this industry may change as the recovery continues.

Ultimately, however, both poor pay quality and high turnover are the result of national policy choices. Research shows that low-wage workers in the United States lack bargaining power over wages, and as such are only able to raise their wages by quitting their jobs for a higher-paying ones elsewhere.

Greater worker power and access to social insurance programs such as Unemployment Insurance are essential for a robust and broadly shared economic recovery

The coronavirus pandemic highlights both how bad-quality jobs put U.S. workers at risk and the how the country’s social insurance system often fails to protect workers from sudden income losses, particularly those in vulnerable service sectors with low levels of unionization. The leisure and hospitality industry is a stark case in point.

A Bureau of Labor Statistics analysis of 2018 data found that most unemployed people who worked in the past year had not applied for Unemployment Insurance benefits, and that those who had worked in leisure and hospitality were among the least likely to apply. Only 12 percent of unemployed people who last worked in leisure and hospitality had applied for benefits since their last job, compared with 26 percent across all industries. The most common reason unemployed workers gave for not applying for Unemployment Insurance benefits was that they did not think they were eligible—a pattern that held during the early months of the pandemic even as the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security, or CARES Act of 2020 expanded eligibility.

Outsized employer power may also reduce Unemployment Insurance benefit usage among low-wage workers in service industries. A recent working paper by Marta Lachowska at the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, Isaac Sorkin at Stanford University, and Stephen A. Woodbury at Michigan State University shows that low-wage workers are less likely to claim benefits, but more than half of this relationship between wages and UI take-up can be explained by the firms themselves: Low-wage workers are clustered in firms that have low rates of take-up.

This is especially true for workers in service industries, the authors find. Service workers not only tend to have lower Unemployment Insurance take-up rates compared with workers in the more unionized goods-producing sectors, but also are more likely to have their claims challenged by their employers, likely deterring future claims by workers at those firms. Low-road firms can also affect employee-claiming behavior by failing to notify workers of potential eligibility, actively discouraging claim filing, or structuring employment arrangements so workers are less likely to qualify for benefits.

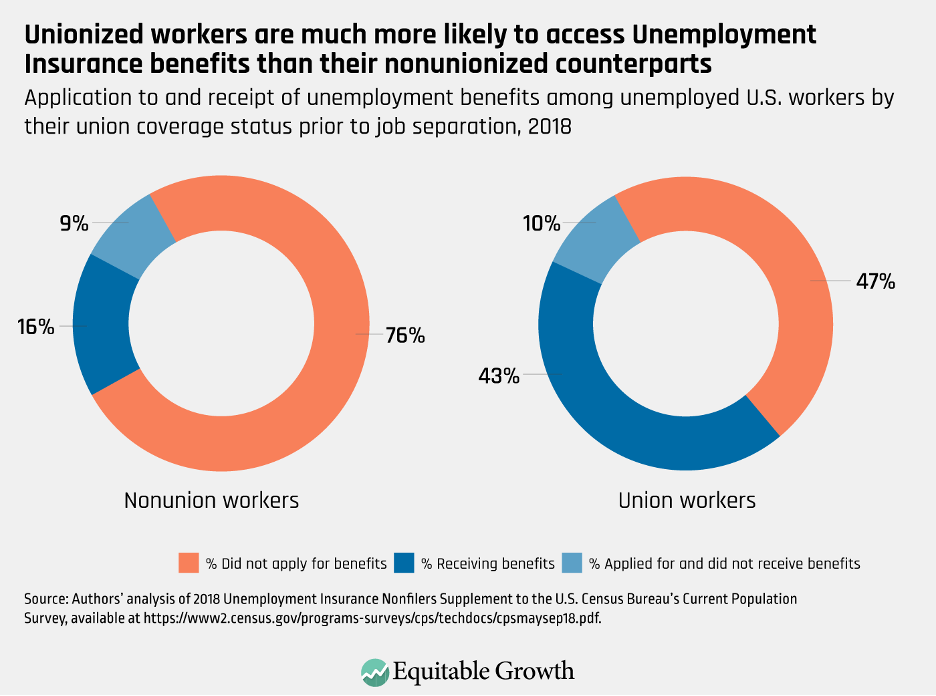

In contrast, greater worker power can support access to unemployment benefits and reduce disparities in Unemployment Insurance take-up. Unions and other labor organizations can help workers learn about Unemployment Insurance, navigate the UI process, protect them from employer responses, and improve job quality conditions around hours and work schedules that can increase UI eligibility. The 2018 Bureau of Labors Statistics data shows that among unemployed workers, unionized workers were twice as likely to apply for UI benefits as nonunion workers—and even more likely to receive them, with 43 percent of unionized workers saying they had received UI benefits compared to only 16 percent of nonunion workers. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

Worker power can improve access to benefits, but Unemployment Insurance can also in turn strengthen worker power. Alexander Hertel-Fernandez at the U.S. Department of Labor and Alix Gould-Werth at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth document the power of the “virtuous circle” connecting unemployment supports to worker voice during the coronavirus pandemic. During April and May 2020, they found that workers who had greater access to UI felt more comfortable participating in collective action to demand better safety and health standards at their workplaces.

To be sure, legislative action at the national and state level expanded eligibility and benefit amounts for unemployed workers in the early months of the pandemic. But a working paper from Eliza Forsythe at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign finds that the share of all unemployed workers who received Unemployment Insurance benefits in the previous two weeks was only 16 percent in April 2020, and peaked at only 32 percent in October of that year. And as state unemployment offices were overwhelmed by the sudden rise in applications, millions of workers faced long delays in receiving their jobless benefits, leaving them without much-needed income for weeks or months.

Conclusion

Amid disappointing employment numbers, the U.S. economy continues to face a 3.6 million jobs deficit compared to its pre-pandemic levels. Moreover, the latest Employment Situation Summary reflects data from the first half of December, meaning that these numbers do not capture the full extent to which the massive surge in COVID-19 cases affected workers and industries.

The challenges that low-wage workers face both receiving jobless benefits and with bad-quality and unsafe working conditions amid the ongoing coronavirus pandemic underlines the urgent need for Unemployment Insurance reform. Job displacement leads to lasting effects on workers’ careers and wages, particularly for Black workers and other workers of color. But extended Unemployment Insurance and other income support programs can help displaced workers find better jobs that better match their skills, with the greatest benefits for women, workers of color, and workers with lower levels of formal education.

Meanwhile, other existing income supports such as the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families are too difficult to access, with intentionally restrictive eligibility requirements and benefit amounts that are inadequate for families’ needs. These dynamics highlight the need to remove barriers that keep the nation’s social infrastructure programs from functioning effectively for workers, families, and the entire economy. Investments in the rest of the country’s social infrastructure are also needed so that workers and families can reach accessible and high-quality caregiving services, as well as paid leave. These policies will be key for a broadly shared and thus more resilient economic recovery.