How to replace COVID relief deadlines with automatic ‘triggers’ that meet the needs of the U.S. economy

To strengthen the federal government’s response to the coronavirus pandemic and the resulting economic downturn, President Joe Biden seeks to enact his American Rescue Plan to stop the spread of the coronavirus and COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus, provide relief to devastated families and businesses, especially those headed by Black and Latinx Americans who are bearing the brunt of the economic pain, and stimulate the U.S. economy as it struggles to recover from recession.

President Biden’s far-reaching proposal includes a number of critical enhancements to key programs that support families and buttress consumption. But there is one problem: The Biden plan includes arbitrary cut-off dates that halt emergency programs regardless of the state of the U.S. economy. In a few instances, the plan allows for the possibility of automatic extensions, but it contains no specifics. No matter how high unemployment remains when these programs expire, Congress would be forced to go through yet another challenging and unpredictable legislative negotiation to continue them.

As we saw this past July, after some the provisions in the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security, or CARES, Act expired, and then again in December, when the remainder of those provisions ended, premature expirations of aid leave suffering families uncertain about putting food on their tables, exacerbate preexisting challenges facing program administrators, and undermine economic recovery as consumers cut back spending in fear of what might come next. Unemployment Insurance beneficiaries, for example, suffered from significant delays and lapses over the course of 2020 due to the various congressional stalemates, as well as the UI system’s chronic problems.

There is a solution to this problem. The next coronavirus relief bill can be written to keep critical benefits in place until they are no longer needed. So-called off-triggers that depend on economic data can ensure that benefits phase out as the economy recovers, not on a random date. There are a number of possible mechanisms that can serve as off-triggers, winding down enhanced benefits based on the state of the economy in individual states and nationally.

Automatic stabilizers

Programs that expand in a recession, such as Unemployment Insurance, are known as automatic stabilizers, as they help to stabilize a weak economy automatically. But policymakers and economists alike have seen time and time again that in past recessions—and the current one—the current structure of these programs provides too little too late to either stop the U.S. economy from declining or revitalize it so that workers are reemployed, wages rise, and families can feel secure. So, Congress routinely steps in to boost benefits—especially for programs such as Unemployment Insurance and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, formerly known as food stamps—and lengthen their duration. But the partisan wrangling that often afflicts Congress usually delays assistance at the beginning of a recession, and the assistance falls short. Then, Congress struggles to extend benefits, often letting the programs lapse for spells or prematurely pulling the plug altogether.

This was certainly true during and after the Great Recession of 2007–2009. As Rep. Don Beyer (D-VA) recently noted, “In the Great Recession, they re-upped Unemployment Insurance 13 different times. That’s 13 political battles between the House and the Senate, needing 60 votes and the president.” The result of inadequate and unreliable support from the federal government was a long, drawn-out recovery in which the U.S. labor market took years to recover its vitality and the economy was characterized by lagging employment, wage growth that was sluggish at best, and continuing anxiety and financial challenges for U.S. workers and their families.

Recession Ready

What was lacking in the Great Recession, and what is needed now, is a mechanism for ensuring that benefits remain available as long as they are necessary, with no need to wait for Congress to act. There are a number of solid, evidence-based ideas for such a mechanism. In 2019, the Washington Center for Equitable Growth and The Brookings Institution’s Hamilton Project published Recession Ready, a book of essays with comprehensive plans to strengthen automatic stabilizers, including recommendations for automatic triggers to activate supplemental benefits to families and state governments, and automatic triggers to turn them off.

Before the next recession, it will be important to establish on-triggers that automatically implement supplemental benefits without the need for new legislation when economic data make it clear that a recession is imminent or already occurring. But at this moment, what is important is that off-trigger mechanisms be included in the COVID relief legislation now being debated in Congress. The House and Senate have already seen the introduction of several bills that contain such mechanisms. Most of these proposals focus on the level of unemployment or on health conditions, either nationally or by state, and vary in technical ways. Fundamentally, however, they are all intended to sustain spending until job markets have sufficiently recovered.

Options for off-triggers

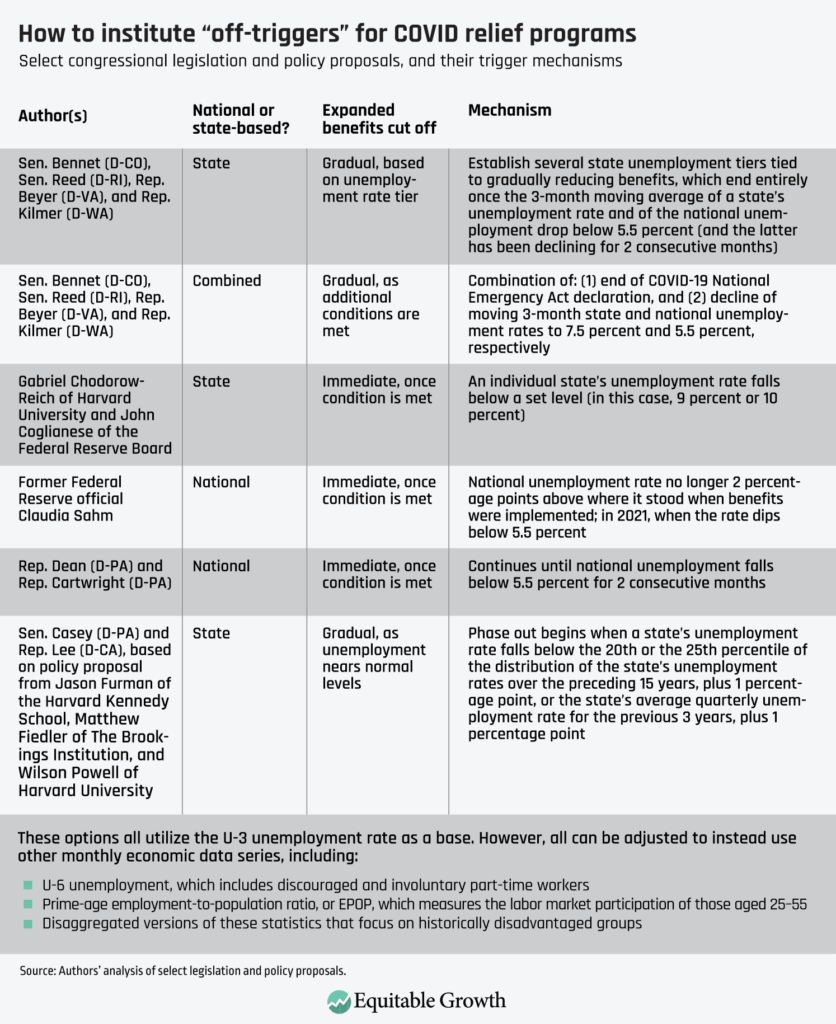

There are a number of ideas for ensuring that unemployed workers do not prematurely lose any of the special Unemployment Insurance benefits enacted by Congress when, on March 14, they would expire under current law, including extended benefits, supplemental payments, or the inclusion of workers who are usually not eligible for the program. These same ideas could be considered for when President Biden’s American Rescue Plan would end them at the end of September. Essentially, these off-triggers retain extended benefits until the economy improves to a sufficient level. (See Table 1.)

Table 1

Sens. Michael Bennet (D-CO) and Jack Reed (D-RI) and Reps. Beyer and Derek Kilmer (D-WA) introduced legislation in 2020 to extend and increase unemployment benefits. The legislation divides the states into six tiers based on their rate of unemployment and reduces or increases various types of benefits based on the tier where each state, as well as the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and other U.S. territories, falls over time, with additional benefits phasing out entirely when the 3-month moving average of their individual unemployment rate drops below 5.5 percent and the 3-month moving average of the national unemployment rate is below 5.5 percent and has been declining for 2 consecutive months.

They also propose to mix in a trigger based on public health, by supplementing weekly unemployment benefits by $600 (as opposed to the current $300 weekly supplement and the $400 weekly supplement proposed by President Biden) until the end of the COVID-19 National Emergency Act declaration first issued by former President Donald Trump in March 2020. The benefit would then decline to $450 for 13 weeks, and then to $300 or $200 depending on the state’s tier, ending completely in a state when the state’s 3-month moving average unemployment rate sinks below 7.5 percent and the 3-month moving average of the national unemployment rate is below 5.5 percent and has been declining for 2 consecutive months. The bill allows for the resumption of the $600 payment if the emergency declaration is extended or a new COVID-19 emergency occurs.

Another measure tied to unemployment benefits is a Recession Ready proposal by Gabriel Chodorow-Reich of Harvard University and John Coglianese of the Federal Reserve Board. The authors add two triggers to the normal extended Unemployment Insurance triggers to lengthen benefits for longer periods: to a total of 60 weeks (including the original 26 weeks) when a state’s unemployment rate crosses 9 percent and to 73 weeks when a state’s unemployment rate crosses 10 percent. This trigger is based simply on state unemployment rates.

Unemployment rates are also the basis for off-triggers for other proposed automatic stabilizers. Another Recession Ready proposal put forward by former Washington Center for Equitable Growth Director of Macroeconomic Policy Claudia Sahm suggested a system of annual direct stimulus payments during recessions. They would be triggered by a sustained rise in unemployment and would continue annually if the national unemployment rate stayed 2 percentage points above the level at the time of the first payment. Using the $2,000 payments enacted early during the pandemic as an example, the off-trigger would be achieved when the unemployment rate falls below 5.5 percent, which is 2 points higher than the rate in February 2020.

Similarly, Reps. Madeleine Dean (D-PA) and Matt Cartwright (D-PA) recently introduced the Payments for the People Act, which would send most families quarterly rather than annual payments. The amount would be based on the national level of unemployment, and their off-trigger is simple and not set by a formula. Payments would just continue until the national rate of unemployment falls below 5.5 percent for 2 consecutive months.

And then, there is legislation introduced by Sen. Bob Casey (D-PA) based on the Recession Ready Medicaid and Child Health Insurance Program proposal of former Chair of the President’s Council of Economic Advisers and current Equitable Growth Steering Committee member Jason Furman, Matthew Fiedler of The Brookings Institution, and Wilson Powell III of Harvard University. Rep. Susie Lee (D-NV) introduced a similar measure in the House, and the Take Responsibility for Workers and Families Act—a coronavirus relief measure introduced by House Democratic leadership in 2020—also contained a similar provision.

Both the legislation and the program by Furman and his co-authors establish on- and off-triggers related to state unemployment rates. They would make a state eligible for increased support in any quarter in which its unemployment rate exceeded a threshold level, set by a formula designed to ensure that it is targeted to serious downturns rather than small fluctuations in unemployment. The Furman proposal would make a state eligible for relief in any quarter in which its unemployment rate exceeded the 25th percentile of the distribution of the state’s unemployment rates over the preceding 15 years, plus 1 percentage point. The percentile measure is intended to approximate the state’s unemployment rate at full employment. This additional percentage point allows for normal fluctuations and ensures that the trigger is targeted to serious economic downturns.

The Casey and Lee bills differ somewhat in that the trigger is unemployment exceeding the lower of either the 20th percentile of the distribution of the state’s quarterly unemployment rates for the most recent 60-quarter period, plus 1 percentage point, or the state’s average quarterly unemployment rate for the previous 12-quarter period, plus 1 percentage point. Under all of these formulas, the amount of additional federal support would depend on the extent to which a state’s unemployment rate exceeded the threshold.

The increased support would continue based upon quarterly assessments of each state’s unemployment rate and would phase out using the same triggers. Effectively, as a state’s unemployment rate declined, its level of additional support would also decline, until the state fell below the initial threshold, at which point additional federal spending would cease.

The labor market indicators used for off-triggers generally use the traditional unemployment rate known as “U3,” which measures the number of people actively looking for work. But policymakers could choose to use other measures, such as “U6,” which includes discouraged and involuntary part-time workers; the prime-age employment-to-population ratio, or EPOP, which is a measure of the labor market participation rate of those ages 25 to 55; or even disaggregated versions of these statistics that focus on the employment prospects of historically disadvantaged groups that tend to lag behind national averages. There are pros and cons to each of the possible alternatives, but all of them would be an improvement on no triggers at all.

A different kind of off-trigger is proposed by Hilary Hoynes of the University of California, Berkeley and Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach of Northwestern University, whose Recession Ready proposal is to increase the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program’s maximum benefits by 15 percent during periods of high national unemployment. They propose an off-trigger similar to one included in the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act based on the food assistance program’s typical inflation indexing. Under their plan, the new maximum benefit would remain in place until inflation in food prices raised the previous maximum by that same amount, presumably a period of some years. At that point, when the original maximum benefit caught up with the 15 percent increase, the supplement would effectively disappear and benefits would resume increasing with inflation.

Conclusion

There are a number of ideas for Congress and the Biden administration to consider, but whatever they choose, it is important to note that the enactment of triggers in place of cut-off dates does not preclude additional action by Congress. When enhanced benefits or payments are set to expire automatically because of an off-trigger, but policymakers believe that conditions have not recovered sufficiently, Congress can bypass the trigger and keep additional spending in place. Or they can boost support even further by delivering, for example, monthly direct payments. Of course, the opposite is also true: Congress can determine that the economy has recovered sufficiently before an off-trigger is reached, and reduce or shut down the additional payments. Triggers are a backstop, not a replacement, for legislative action.

While they may be only a backstop, off-triggers are far superior to artificial stop dates. Because they don’t include such a date, including them in the next coronavirus package might increase the bill’s sticker price, as calculated by the Congressional Budget Office. But the cost, in human suffering and economic uncertainty, of an arbitrary and premature expiration date would surely be higher.

If relief and aid programs are inadequate, and if they depend on Congress returning again and again to extend them, then these measures are fighting with one hand tied behind their backs. Establishing off-triggers maximizes the power of relief measures and assures the workers and families depending on this support that Congress will not allow benefits to lapse. The new Congress and the new administration should enact them now, and let these programs do their essential work.