How the coronavirus recession is impacting part-time U.S. workers

The coronavirus recession continues to highlight and deepen the structural inequities that have long made the U.S. economy so fragile.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ monthly Employment Situation Summary—also known at the Jobs Report—the unemployment rate fell from 14.7 percent in April to 13.3 percent in May and the economy recovered 2.5 million nonfarm payroll jobs. After prime-age employment experienced the steepest decline in history in April, the share of the population aged 25 to 54 that has a job rose to 71.4 percent in May.

But the Jobs Report also shows that May’s decline in joblessness was mostly driven by White workers, whose unemployment rate went from 14.2 percent in April to 12.4 percent in May. The unemployment rate of Hispanic workers also fell, albeit less so and still standing at unprecedented levels, going from 18.9 percent to 17.6 percent. Meanwhile, the joblessness rate for Black workers actually climbed from to 16.7 percent in April to 16.8 percent in May.

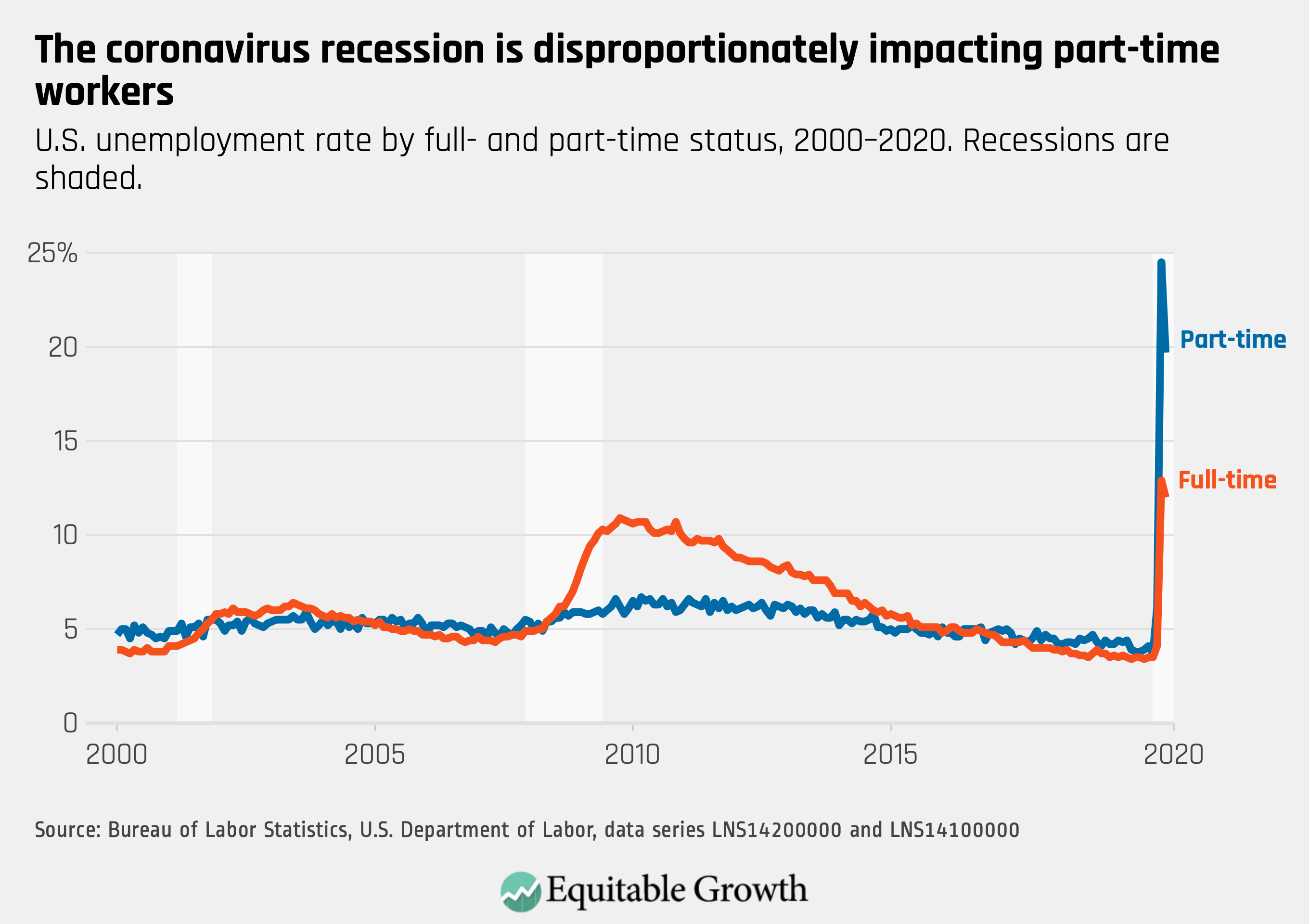

Part-time workers are also among the hardest hit by the coronavirus recession. They have accounted for almost one-third of the decline in employment since pre-pandemic February, despite making up less than one-sixth of the U.S. workforce. Between February and May, the unemployment rate of part time workers surged from 3.7 percent to 19.7 percent. The unemployment rate for full-time workers has increased at a much slower pace, going from 3.5 percent to 12 percent. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Even before the current economic downturn, part-time workers—those working less than 35 hours per week—were already an especially vulnerable segment of the workforce. Part-time workers are disproportionately women of color, are much more likely to experience financial strain, and are much less likely to receive benefits such as paid holidays, health benefits, and family leave. For instance, even though more than 70 percent of U.S. workers have access to paid sick leave, less than half of part-time workers do.

Young workers and those 65 and older—groups that have consistently been among the hardest hit by recessions—are also overrepresented among those doing part-time jobs. This means some of the workers most affected by the current downturn are also among the least likely to have the financial resources to ride out the recession.

Even though it is not surprising that part-time workers have smaller annual and weekly earnings than their full-time peers, a new study by Lonnie Golden of Penn State University advances previous research that shows they experience an hourly wage penalty, with part-timers making 20 percent less per hour than workers with comparable levels of education, demographic characteristics, and working jobs in the same industry and occupation. This penalty is especially burdensome for Black and Hispanic women, who are also overrepresented among those who would like to work more hours but are not able to because of slack labor market conditions or because they could only find part-time jobs.

The massive 7.7 percentage point unemployment gap between part-time workers and their full-time counterparts also points to how the coronavirus recession is different from the previous downturn. In the worst months of the Great Recession of 2007–2009, full-time workers faced an unemployment rate that almost doubled that of their part-time peers. That the opposite is now true is, in part, explained by part-time workers’ overrepresentation in the service occupations being the hardest hit by the coronavirus pandemic and ensuing recession. Similarly, this occupational composition helps explain why part-time workers experienced a bigger decline in joblessness this month, with the leisure and hospitality industry gaining 1.2 million jobs—almost half of the employment gains between mid-April and mid-May.

Part-time workers’ unemployment toll is particularly concerning in the context of the current crisis. Many of them are taking on new caregiving responsibilities and may need positions that demand fewer hours. What’s more, part-time workers are experiencing delays and barriers to access unemployment benefits, much like what is happening to independent contractors and the self-employed. Increasing unemployment insurance through proposals included in the Heroes Act, which just passed the U.S. House of Representatives, would work as a mechanism for macroeconomic stabilization, making this recession shorter and less severe. It also would represent a step forward in alleviating long-standing disparities that have prevented many workers, and especially Black workers, from receiving benefits.

Policymakers should also help part-time workers by ensuring these positions are well-paid and secure by expanding access to basic benefits such as paid family leave and paid sick leave—benefits to which Black workers, who are also particularly impacted by recessions and left behind by recoveries, have less access to than their White peers. There should also be increased federal support for the Children’s Health Insurance Program, which has helped leveling the playing field by providing important support to families of color. In this way, the care responsibilities of many part-time workers would be more stable and sustainable.