Honoring Black History Month: How the history of violence and systemic racism continue to impact economic outcomes for African Americans

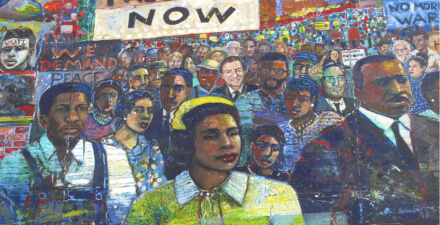

Dominance and violence rooted in institutionalized racism, systemic oppression, and colonization are often to blame for the inequality that many African Americans endure today. This year’s celebration of Black History Month follows a year wrought with violence and blatant acts of racism. While it may be easier to label the more-apparent atrocities, it is equally, if not more, important to highlight the lingering impact that the historical underpinnings associated with racism and oppression have on the quality of life many African Americans struggle to obtain.

The National Economic Association organized sessions at this year’s Allied Social Sciences Associations conference to elevate research that does just that. Through papers presented at sessions such as “Economics of Racism” and “Racial Discrimination and Disparities: Effects of Institutional and Historical Factors,” academics sought to highlight research into how the economic consequences of past racist acts and policies continue to reverberate today through institutions and policies.

As an example of how deeply rooted racism is today in American culture, society, and policy, RAND economist Jhacova Williams’ paper, “Confederate Streets and Black-White Labor Market Differentials” examines what the persistent symbols of our racist past can tell us about labor market conditions today. In this paper, Williams studies the association between streets named after Confederate generals and differences in labor market outcomes between White and Black workers in those areas today.

Hypothesizing that the continued presence of streets named in honor of people who fought to preserve slavery serves as a proxy for the persistence of racist attitudes, Williams finds that “Blacks who reside in areas with a relatively higher number of Confederate streets are less likely to be employed, more likely to have low-status occupations, and have lower wages compared to their White counterparts.” In addition, differences in labor market outcomes in these areas are observed not just between White and Black workers, but also between White workers and other workers of color.

These findings are descriptive, not causal, but they nonetheless suggest that there’s something about the places that celebrate the symbols of the Confederacy that influences mechanisms shaping labor market outcomes, such as investment in public education, outright discrimination in the labor market, or state minimum wage laws.

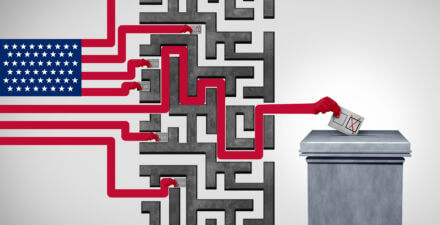

Another mechanism that shapes U.S. labor market outcomes is whether and how labor laws are actually enforced. One example of this comes from the work of University of Memphis economists Jamein Cunningham and Jose Joaquín Lopez. In a presentation of preliminary findings from their work funded by Equitable Growth, “Civil Rights Enforcement and the Racial Wage Gap,” Cunningham and Lopez explore how private enforcement of anti-discrimination legislation—the right to which was established by the Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and 1968—could influence local racial wage divides. Though still very preliminary, this research project is an example of how we can model the role of institutions such as the legal system to understand their impact on economic outcomes.

Cunningham and Lopez’s preliminary results show that a relationship exists between court rulings and labor market outcomes, though they caveat that many instances of labor market discrimination will not even be litigated because the onus is on the affected party to take on initial costs of bringing a case, and even of the cases that are brought, many will be settled out of court. “Enforcement, as measured by plaintiff win rates in nondismissal judgments, reduces the wage gap for Black males by 3.4 percentage points (19 percent reduction in wage gap) and by 7.7 percentage points for Hispanic men,” the co-authors find. “The impact of plaintiff win rates is much larger for women; reducing the wage gap by 71 percent for Black women and by 50 percent for Hispanic women.”

While these results are also just descriptive, they demonstrate that court enforcement plays a role in shaping local labor market decisions and that further research into the mechanisms explaining this relationship could help improve our understanding of the role of institutions in shaping how policy is implemented and therefore actually influences people’s economic experiences.

It is not just via seemingly race-neutral labor market policies that nonetheless have a disparate impact on the economic outcomes of Black Americans that the economic mobility of African Americans is obstructed—it is also through overt acts of physical violence. Lisa Cook, professor of economics and international affairs at Michigan State University, a member of the Washington Center for Equitable Growth’s Steering Committee, and chair of the “Economics of Racism” session at the ASSAs, has done groundbreaking work to quantify the impact of racist violence on economic growth and innovation.

In her paper, “Violence and Economic Activity: Evidence from African American Patents, 1870 to 1940,” Cook studies how the rise in mass violence directed at Black Americans following the end of slavery resulted in less inventive activity and found that “extrajudicial killings and loss of personal security depressed patent activity among Blacks by more than 15 percent annually between 1882 and 1940.”

Cook looked at patent filings as an indicator of inventive activity and how the rise in extrajudicial violence against Black Americans over the course of the late 19th and early 20th centuries affected the creative economic activity of Black and White inventors. Looking at how patent activity among Black inventors varied, compared to that of White inventors, after race riots and across states as they adopted Jim Crow segregationist laws, Cook found that “the sense among African American inventors and other economic agents that hate-related violence would likely not be adjudicated and that the rule of law, typically through federal government intervention, would likely not prevail” depressed U.S. inventive activity by 1 percent per year.

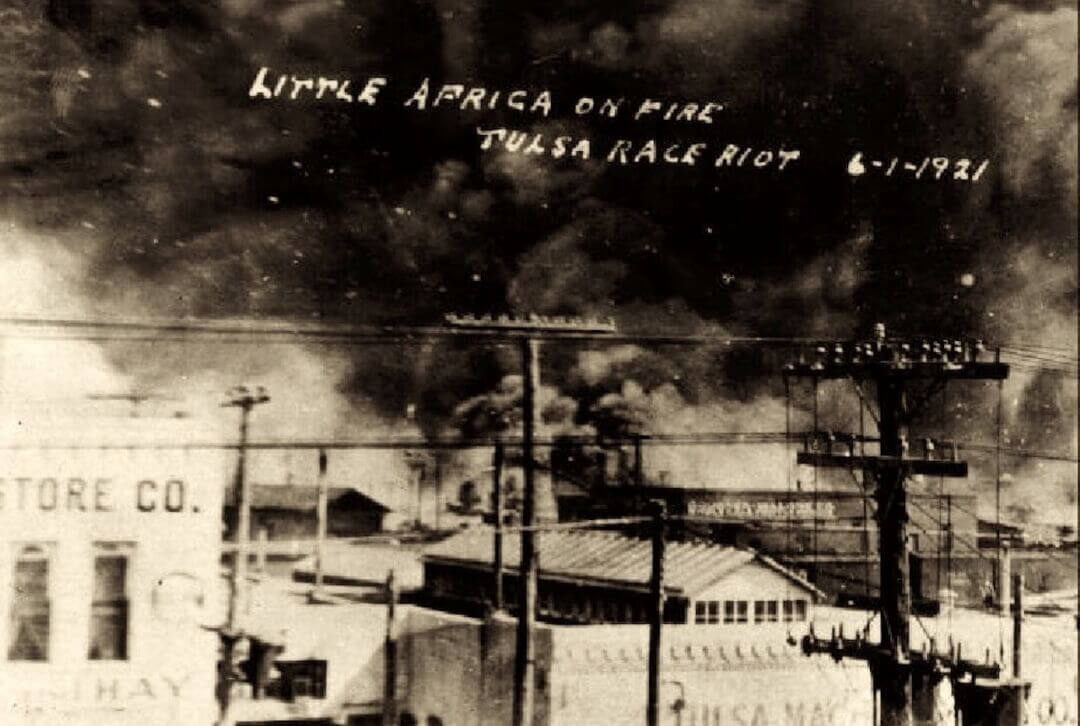

Cook’s research is an example of economics research that attempts to quantify the economic impact of the violence that was directed toward African Americans and is a parallel to the work of other scholars such as Mehrsa Baradaran, a professor of law at the University of California, Irvine and a member of Equitable Growth’s board. In Baradaran’s book, The Color of Money: Black Banks and the Racial Wealth Gap, she recounts the events of the 1921 Tulsa Race Riots and the destruction of what was known to many as Black Wall Street. Once the wealthy, predominantly African American community in Tulsa was perceived as a threat to White supremacy, it was destroyed at the hands of White rioters and its economic prosperity was never restored.

Generations of violence, predatory financial practices, and labor market discrimination have stolen opportunities—and billions of dollars—from African Americans. Research presented at the ASSA conference highlighted both the historical and ongoing significance of racial violence, alongside structurally racist institutions and norms used as tools used to isolate Black Americans while reserving and creating opportunities for White Americans. As a result, profound racial divides exist across all indicators of success, including access to quality education, high-paying jobs, and, as illuminated by the coronavirus pandemic, quality healthcare.

Let us remember as Black History Month draws to a close that the same policies, laws, and practices that were designed to promote racial violence and inequity can be redesigned to restore humanity.