Fool Me Once: Investing in Unemployment Insurance systems to avoid the mistakes of the Great Recession during COVID-19

Overview

Thousands of laid-off workers in Massachusetts unable to access the state’s Unemployment Insurance website. Kentucky, North Carolina, and Ohio experiencing full system outages. Nevada Unemployment Insurance applicants stuck at busy signals and hold messages. A civil engineer in Florida stumped by the arcane benefit application system. And 9 in 10 Californians with unprocessed claims and missing benefits in the dark about their cases.

The outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic and the COVID-19 disease it spreads has moved many sectors of the U.S. economy to a near-standstill, and state Unemployment Insurance systems are overwhelmed by the number of claims, as an unprecedented more than 1 in 7 workers apply for benefits. The examples in the previous paragraph, however, predate the current crisis by years. During the Great Recession of 2007–2009 and its aftermath, unemployed workers across the country struggled to access the unemployment benefits to which they were entitled, and our government—at both the state and federal levels—failed to remedy the systemic problems that prevent workers from accessing benefits and thus lead to personal financial hardship and a muted economic stimulus.

In the early days of the coronavirus recession, we have seen the problems of the Great Recession echoed in the administrative failures of state Unemployment Insurance agencies. The current disarray in state unemployment benefits programs is neither a surprise nor an accident. It is the result of decades of conscious choices made by policymakers at the state and federal level: Over the past decade, many states limited Unemployment Insurance benefits, made accessing the program more difficult, and refused to fully fund it.

With policy as it stands, we will also repeat problems with benefit extensions at the crisis’s middle and the depletion of trust funds and erosion of benefit levels at the crisis’s end. And, as was the case in the Great Recession, in the first months of the coronavirus crisis, policymakers today refuse to remedy the issues at the heart of these administrative failures. But it’s not too late.

To be able to respond nimbly to the next twists and turns in the coronavirus recession, policymakers should address three key structural flaws in the nation’s Unemployment Insurance program as soon as possible:

- Increase the federal taxable wage base to the same level as the Social Security taxable wage base and index it to inflation so that states have adequate resources for program administration

- Redesign benefit extensions so that the program responds quickly and efficiently to macroeconomic changes

- Implement a standardized minimum benefit level and minimum benefit duration that are generous enough to incentivize workers to apply for benefits

Before turning to these policy recommendations, however, this issue brief sets the stage by examining the current state of the Unemployment Insurance program.

What’s now in place: The Unemployment Insurance response to the coronavirus recession

Policymakers have chosen Unemployment Insurance as the primary program to use to disburse resources to people in the crosshairs of the current economic crisis. This choice makes sense: For 85 years, Unemployment Insurance has served as the main government program designed to assist workers who lose a job through no fault of their own and stabilize the U.S. economy in times of macroeconomic contraction. The basic premise of how Unemployment Insurance should facilitate economic stabilization is simple:

- In good economic times, employers pay small amounts into Unemployment Insurance trust funds.

- When unemployment rises, workers receive benefits from the trust funds.

- They spend the money they receive, countercyclically sustaining demand when the economy needs it most.

- When unemployment abates, workers draw fewer benefits and employers’ profits increase, allowing the government to replenish trust fund coffers.

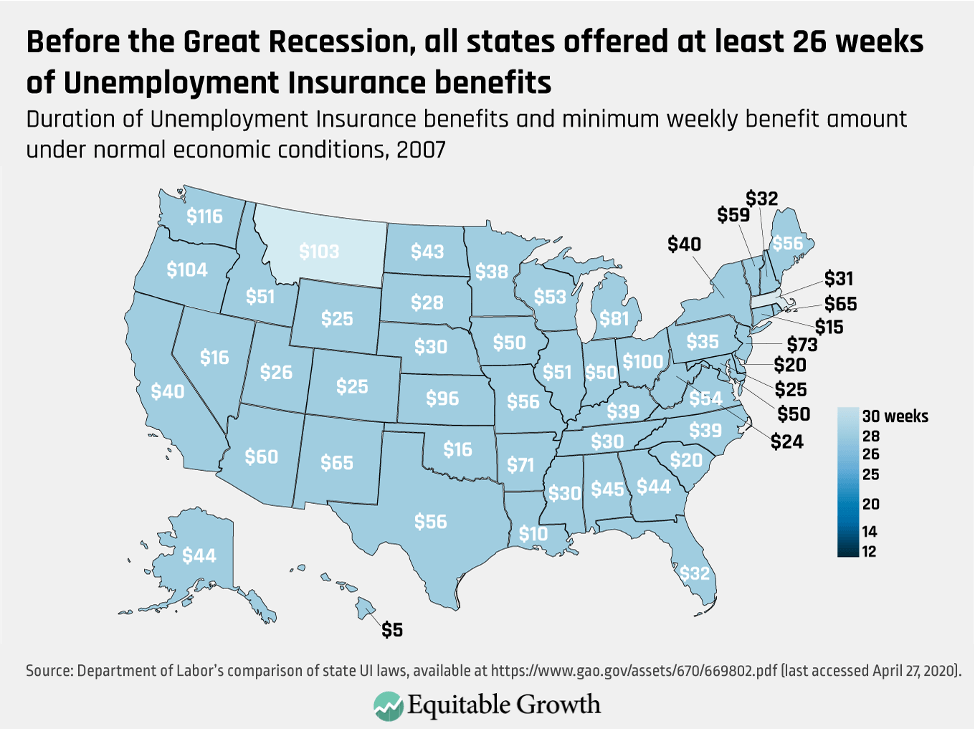

Unemployment Insurance is run through a state-federal partnership, with the federal government setting program requirements and providing funding for program administration, and states setting the day-to-day rules governing benefit levels and program administration. In normal times, people who lose jobs through no fault of their own are eligible for 12 weeks to 30 weeks of state-funded Unemployment Insurance benefits—benefit length is set by the states, with most providing 26 weeks.

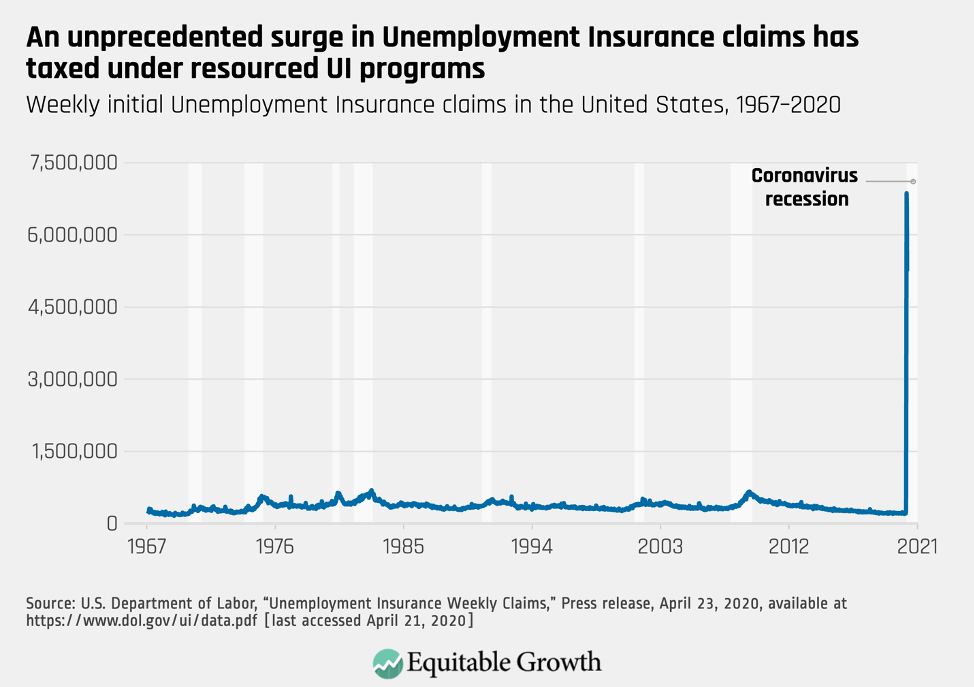

The current economic crisis is unlike any in recent memory because of the speed at which businesses closed their doors, the magnitude of the shock, and the fact that many workers cannot and should not search for work as usual. Figure 1 shows the magnitude and speed at which the surge in Unemployment Insurance applications occurred (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

To respond to the atypical nature of this crisis, federal policymakers made key changes to the Unemployment Insurance system. They gave states the latitude to waive work-search requirements for Unemployment Insurance claimants whose ability to search for work is impeded by the pandemic. They extended the length of benefits by 13 weeks for those affected by the pandemic, and they also increased the benefit amount by $600 per week until the end of July.

This extra $600 a week per claimant means that the average worker will have her full wages replaced during this period. What’s more, federal policymakers created a special program called Pandemic Unemployment Assistance for people who are not eligible for regular unemployment benefits whether because they have earned too little, are self-employed, or have exhausted their benefits. People who receive Pandemic Unemployment Assistance will receive the same higher benefit amount and longer benefit duration as those who access regular state Unemployment Insurance.

Each of these changes has the potential to improve the life chances of workers affected by the coronavirus recession and contribute to the stabilization of the macroeconomy. But the benefits are only as good as workers’ ability to receive them—and state Unemployment Insurance agencies face the herculean task of processing an unprecedented number of applications at the same time that they modify and update their systems to disburse enhanced pandemic benefits, all with insufficient resources and technology.

As a result, workers are struggling to access the unemployment benefits to which they are entitled under the law. They are stymied by faulty websites, jammed phonelines, and antiquated computer systems, none of which are ready to disburse enhanced pandemic unemployment benefits. And all of these enhancements are already on a clock that is winding down. All programs expire at the end of the calendar year (with the higher weekly benefit amount ending in July) even if the economic crisis stretches on, as it is expected to.

Though the magnitude of this crisis is unique, the problems facing our Unemployment Insurance system aren’t new. A little more than a decade ago, huge numbers of workers across the country faced administrative barriers to the program during the Great Recession and its aftermath, and those who did gain access to unemployment benefits were perpetually on the fence, wondering if the program would sunset or if it would be extended. If workers experienced these problems before, and policymakers were aware of them, then why did nothing change? This stasis is the result of inadequacies in three main areas: program funding, automaticity, and benefit levels.

Let’s examine each in turn.

What’s needed: Adequate funding for adequate program administration

How does a government program that is supposed to be the major lifeline for unemployed workers in times of macroeconomic catastrophe find itself operating on decades-old computer systems, understaffed, and ill-prepared to serve its basic function? This state of affairs is neither a coincidence nor a surprise. It is the result of a conscious choice by state and federal policymakers not to provide adequate levels of resources for the program’s operation.

Program administration is funded through federal taxes based on employee payroll—referred to as FUTA taxes after the Federal Unemployment Tax Act. Taxes are collected at a rate of 0.6 percent (the FUTA tax rate is 6 percent, but a 5.4 percent credit is applied for state taxes paid) and are levied on the first $7,000 of earnings for each worker on an employer’s payroll. For a full-time, year-round employee, the FUTA tax is $42 per worker per year.

These taxes are technically charged to employers, but research finds that employers pass the cost on to workers by paying them less. Because most workers earn more than $7,000 in a calendar year, FUTA taxes are regressive. A laid-off hedge fund manager, for example, will receive more money in unemployment benefits than a laid-off car wash attendant, yet both pay the same effective tax.

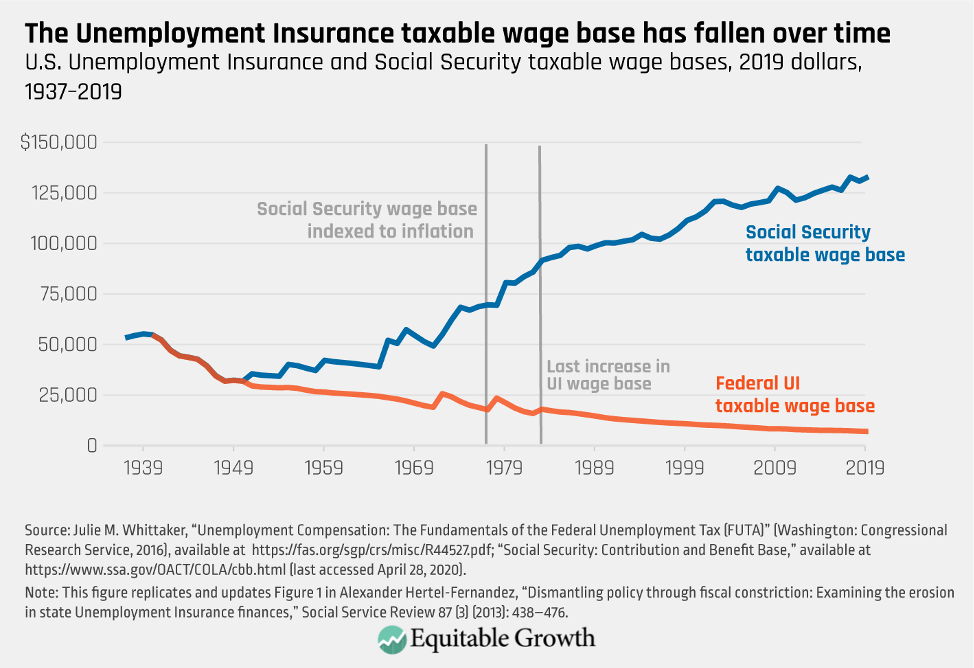

The revenue generated from FUTA taxes is not enough to maintain the program. This revenue is tasked with not only maintaining more than 50 administrative systems but also funding half the cost of the extended benefits that workers receive in times of economic contraction. In 1939, the taxable wage base was $3,000, equivalent to $55,000 in 2020 dollars. Because this amount can only be raised by law (and has only increased three times over the past 80 years), its value has eroded by nearly 800 percent. In contrast, the taxable wage base for Social Security benefits was indexed to inflation in 1977. The chart below shows their divergent histories. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

This trend has been labeled fiscal constriction by scholar Alexander Hertel-Fernandez, and it means that by starving the Unemployment Insurance program of resources, policymakers effectively bind their own hands and purposefully prevent themselves from establishing a modern and efficient system for disbursing benefits. During the Great Recession, we saw the consequences of fiscal constriction clearly. Yet federal policymakers left the taxable wage base at the same level it has been stuck at since 1983, unmoved by the hardship of millions of members of the labor force and unwilling to risk even a small amount of political capital by modestly nudging tax levels upward.

As the old aphorism goes, “fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me.” Now is the time to bring the Unemployment Insurance taxable wage base back to the same level as the Social Security taxable wage base and index it to inflation so that states have the resources they need to deliver benefits efficiently and effectively.

Looking to 2017 as an example and conducting a simple back-of-the-envelope calculation that keeps the FUTA tax rate at 6 percent and applies a 5.4 percent state credit reduction to the $7 trillion of taxable earnings under the Social Security wage base indicates that using this tax base would generate $41 billion. This is a $33 billion dollar increase over the $8 billion in FUTA taxes that were actually collected in 2017.

This additional revenue would provide sufficient funds for Unemployment Insurance system modernization efforts (past grants to states have ranged from $50 million to $200 million), ongoing maintenance, and appropriate staffing. These funds could also be used to provide grants to states to partner with community-based organizations serving vulnerable workers to raise awareness of UI benefits and provide assistance in the application process.

Additional revenue would cover the increased use of the Extended Benefits program and could be used to provide grants to states as they standardize benefit amount and length, as detailed below. Any change to the taxable wage base could be scheduled—for example, occurring when unemployment rates return to prepandemic levels with revenue advanced prior to that time.

What’s needed: The right economic indicators to determine when extra Unemployment Insurance benefits are delivered

When economic times are tough and jobs are hard to come by, finding new work often takes longer than the 26 weeks that Unemployment Insurance benefits typically last. In these circumstances, there are two ways that people can receive additional weeks of benefits. The first is through the Extended Benefits program: When states meet specific economic indicators, residents of the state become eligible for additional weeks of benefits, half of which are paid by the state and the other half of which the federal government pays. The second is when Congress passes new legislation granting benefit extensions and foots the full bill, known as Emergency Unemployment Compensation.

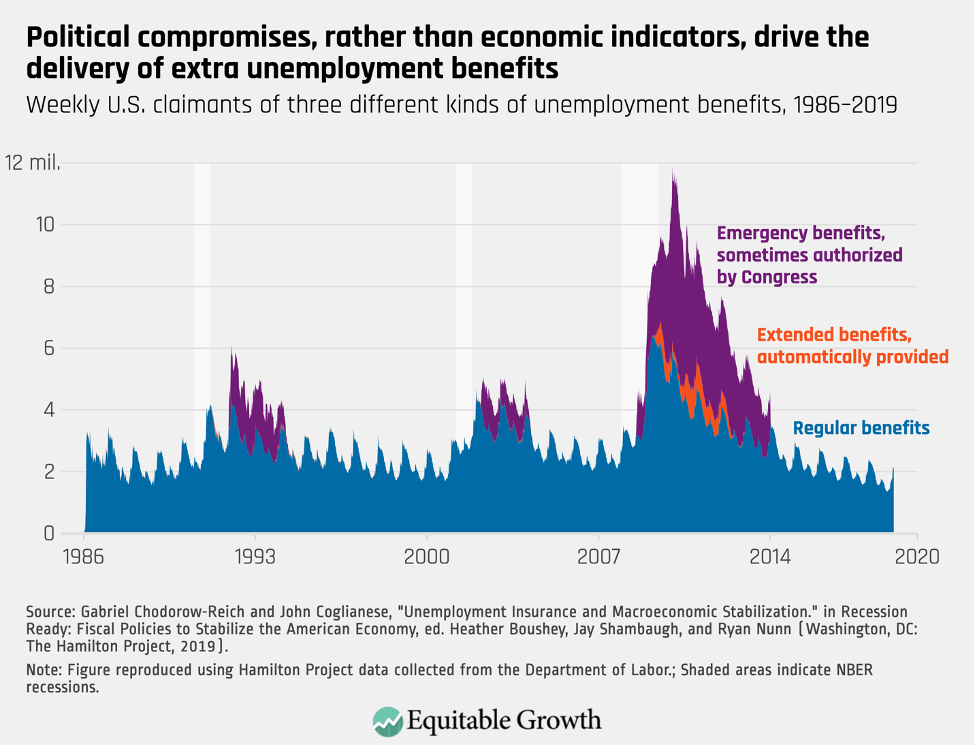

During the Great Recession, most benefits provided to Unemployment Insurance claimants who ran out of normal state-provided benefits before finding new work were delivered through acts of legislation (Emergency Unemployment Compensation) rather than in response to economic triggers (Extended Benefits). (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

The reliance on emergency benefit programs is a reflection of deficiencies in the formulae that states use to determine when Extended Benefits are activated. To activate Extended Benefits, for example, the insured unemployment rate in a given state must be at least 20 percent higher than it was both four and eight quarters prior, and no additional weeks of benefits are provided when the insured unemployment rates climb to levels past 8 percent. This means the Extended Benefits program is not responsive to the most severe recessions—both those that are severe because of their length and those that are severe because of high levels of unemployment. Compounding the problem, as benefits have become more difficult to access, insured unemployment rates have dropped, making it less likely that Extended Benefits will be triggered, even when underlying economic conditions warrant the use of Extended Benefits.

Indeed, looking back over the past three recessions, as detailed in Figure 3, the majority of additional weeks of benefits were provided through Emergency Unemployment Compensation programs rather than Extended Benefits. The coronavirus recession is shaping up to be similar: Congress authorized Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation in the early days of the crisis. Establishing an Emergency Unemployment Compensation program early was the right thing to do. But it came about through an unusual political coalition and is limited to 13 weeks.

As the coronavirus recession stretches on, it will be important that economic indicators—rather than political horse trades—determine the number of weeks of available benefits. Otherwise, we will end up in a situation similar to where we found ourselves during the Great Recession: Unemployed workers waiting on a political compromise to pay the rent and an economy deprived of the stabilization that unemployment benefits provide because of the political calculus of elected officials.

Particularly in the context of the current pandemic, when in-person voting in Washington by members of Congress comes with significant health risks, it would behoove Congress to automatize these processes in lieu of relying on in-person votes. The extension of pandemic-specific benefits should be automatic, and the Extended Benefits program should be improved so that it functions as the automatic stabilizer it was intended to be.

What’s needed: Adequate benefits for effective economic stabilization

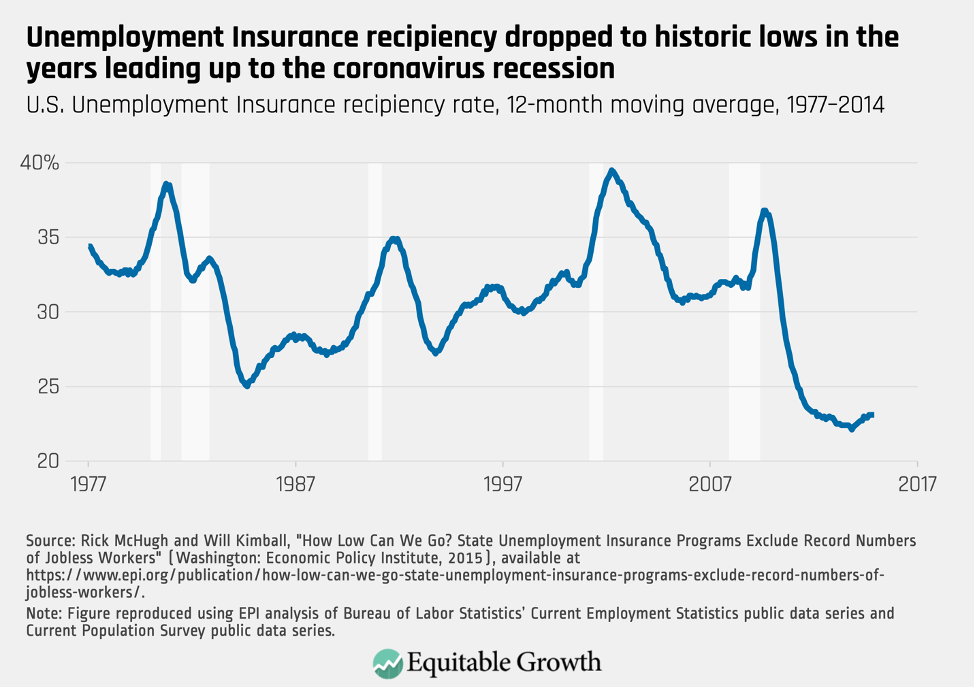

Unemployment Insurance’s function as a macroeconomic stabilizer is not a secret. Its ability to quell economic hardship at the individual level is well understood, too. So, during the Great Recession, federal policymakers made efforts to update the program’s eligibility criteria so that more workers would qualify for benefits. But in the aftermath of the Great Recession, during a slow and uneven recovery, unemployment dollars were not finding their way to the people who needed them. By 2012, rates of Unemployment Insurance claims were at historic lows. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

The importance of the changes that policymakers incentivized during the Great Recession should not be understated, but they were not the essential structural reforms needed to increase benefit receipt, reduce the duration of economic contractions, and attenuate their severity. The key areas for structural change that were overlooked during the Great Recession were benefit levels and the share of the unemployed who are able to access benefits.

Benefit levels affect macroeconomic stabilization in two ways. First, and most obviously, the higher benefit levels are, the more money claimants have to circulate in the economy. Second, benefit levels must be high enough that workers will claim benefits—the higher the level of benefit receipt, the more macroeconomic stabilization will occur. As the coronavirus crisis unfolds, one of the most important tasks for policymakers will be to stabilize the economy.

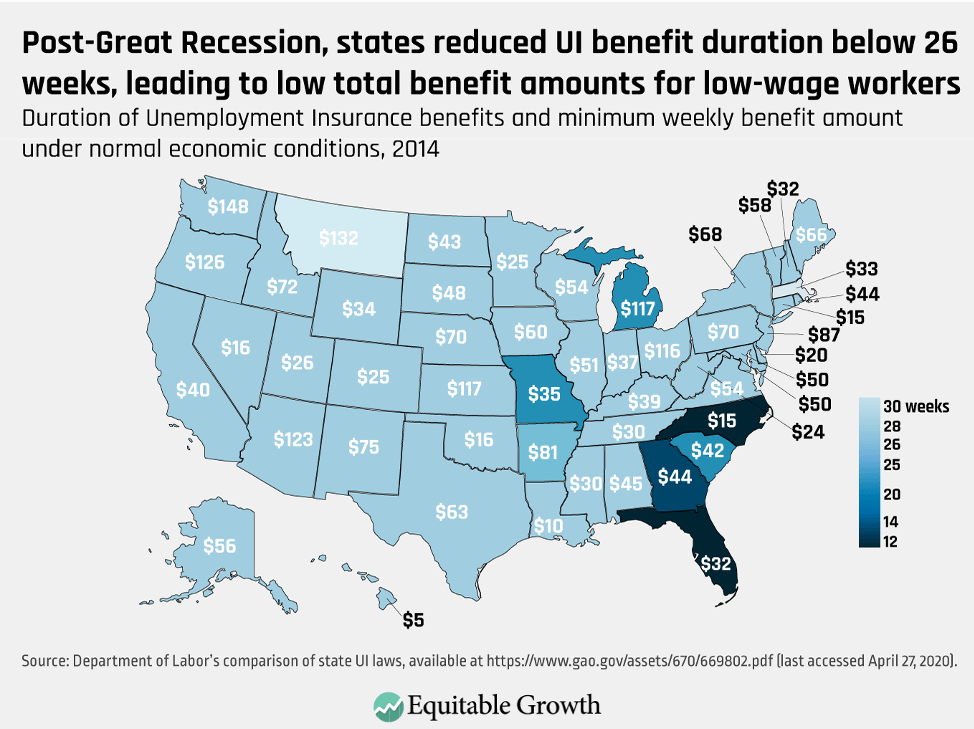

Yet the rise in administrative barriers to benefit applications has been accompanied by a simultaneous drop in benefit levels in many states. Many of these states entered the Great Recession with inadequate resources and were unable to finance benefits without borrowing money from the federal government. Rather than sufficiently increasing their revenues following the Great Recession to pay back the federal government and build up adequate reserves for the next crisis, many states instead cut the number of weeks they would provide benefits for and the amount of money workers receive. (See Figures 5 and 6.)

Figure 5

Figure 6

When Unemployment Insurance benefits are paltry, workers may opt not to claim them at all, given the difficulty involved in applying. Benefit amounts are pegged to earnings levels, which means that the lowest-earning workers receive the lowest benefits. The minimum weekly benefit can be as low as $5, application procedures are difficult due to the disinvestment in administrative systems discussed above, and increasing penalties for overpayments add an additional layer of risk to approved claims.

In addition to searching for work, disadvantaged workers who are unemployed also may need to care for children, arrange for healthcare, address issues with other public benefits, and deal with high levels of stress and anxiety. Given this constellation of factors, it may not be a rational choice to spend time and mental energy on an application process when the payoff is so low.

This is particularly disconcerting given the importance of targeting aid to disadvantaged workers. To have the strongest macroeconomic effect, dollars should go to the people who will spend them most quickly: Disadvantaged workers often receive low compensation for their work, and are more likely to lose their jobs when layoffs begin. These groups of workers, who in some cases have faced generations of labor market discrimination, are usually enmeshed in networks that don’t have the resources to lend a hand in hard times, are less likely to be able to fall back on their own personal savings, and do not typically purchase many unnecessary goods that they can cut back on during an unemployment spell.

When they receive unemployment checks, disadvantaged workers spend them quickly in order to keep medical prescriptions filled, food on the table, and a roof overhead. The money they spend contributes to economic stabilization right away, but if it is not rational for them to go through the process of claiming benefits, then these dollars will never make it to their hands.

When the coronavirus pandemic and resulting economic downturn hit, policymakers recognized the problems with low benefit levels and provided Pandemic Unemployment Compensation, an extra $600 of benefits per week. These extra dollars are a welcome Band-Aid that will help to stabilize the U.S. economy and reduce hardship. But they are time-limited and likely to expire before the economic need for them dissipates, leaving claimants to rely on the low benefit levels of the standard program.

During the Great Recession, policymakers attempted to increase access to insurance benefits by making changes to eligibility criteria. But rather than increase revenue, states responded to financial distress by preventing people from accessing benefits. Today, it is unclear when the coronavirus recession will end. But it will end, and when it does, state coffers will be depleted, and states will once again be tempted to cut corners by cutting benefits.

To avoid putting ourselves in the same situation that we faced at the end of the Great Recession and to ensure that benefit levels are adequate throughout this crisis, policymakers should implement a standardized minimum benefit level and minimum benefit duration that is high enough to incentivize workers to apply for benefits—especially disadvantaged workers. Advocates suggest a minimum benefit level of 60 percent of weekly wages and minimum duration of 26 weeks of benefits.

Conclusion: Policymakers can make these necessary changes now

During the Great Recession, the unemployment compensation system was hamstrung by three key problems: starvation of funding for program administration, use of political calculus rather than economic indicators to determine whether additional weeks of benefits would be available, and a combination of state finances and absence of federal regulation that led states to cut benefit levels. All three problems undercut Unemployment Insurance’s ability to serve as a macroeconomic stabilizer. During and following the Great Recession, policymakers did not address these underlying structural problems, and we have entered the coronavirus recession with an underprepared, fragile unemployment compensation system that we are left to shore up with last-minute fixes in the midst of remote work for many government offices.

As the old aphorism goes, “fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me.” During the Great Recession, policymakers thought that a crisis was not the time to make structural changes in one of the most foundational programs to our economy’s resilience and stability. They were wrong. Now is the time to remedy these flaws, so we are ready for the upcoming twists and turns in the coronavirus crisis and prepared for the next crisis that will come.

The shape this crisis will take over the coming months and years is unclear, but if past is prologue, the political will for Band-Aid fixes will dissipate over time. So, when the next policy window opens, rather than slapping another bandage onto our unemployment system, policymakers should make three key changes:

- Increase the federal taxable wage base to the same level as the Social Security taxable wage base and index it to inflation so that states have adequate resources for program administration

- Redesign benefit extensions so that the program responds quickly and efficiently to macroeconomic changes

- Implement a standardized minimum benefit level and minimum benefit duration that are generous enough to incentivize workers to apply for benefits

Policymakers can learn from the mistakes of the Great Recession and strengthen our nation’s unemployment infrastructure by making these changes. Not doing so would be foolish.